Testing Adaptation Limits: Mariposa Trails, Marin Roads & San Francisco Greenspace

Across California, communities are responding to rapid change, from rising seas and temperatures to intensifying wildfires and floods. KneeDeep’s new quarterly column, “The Practice,” highlights the work of designers, landscapers, engineers and other practitioners on three innovative projects across the state in different stages of planning and completion. Some of these efforts are small-scale and experimental; others are hefty, long-term infrastructure investments. All of them represent the on-the-ground climate adaptation work that doesn’t make big headlines, but is quietly helping California adapt to a future in flux.

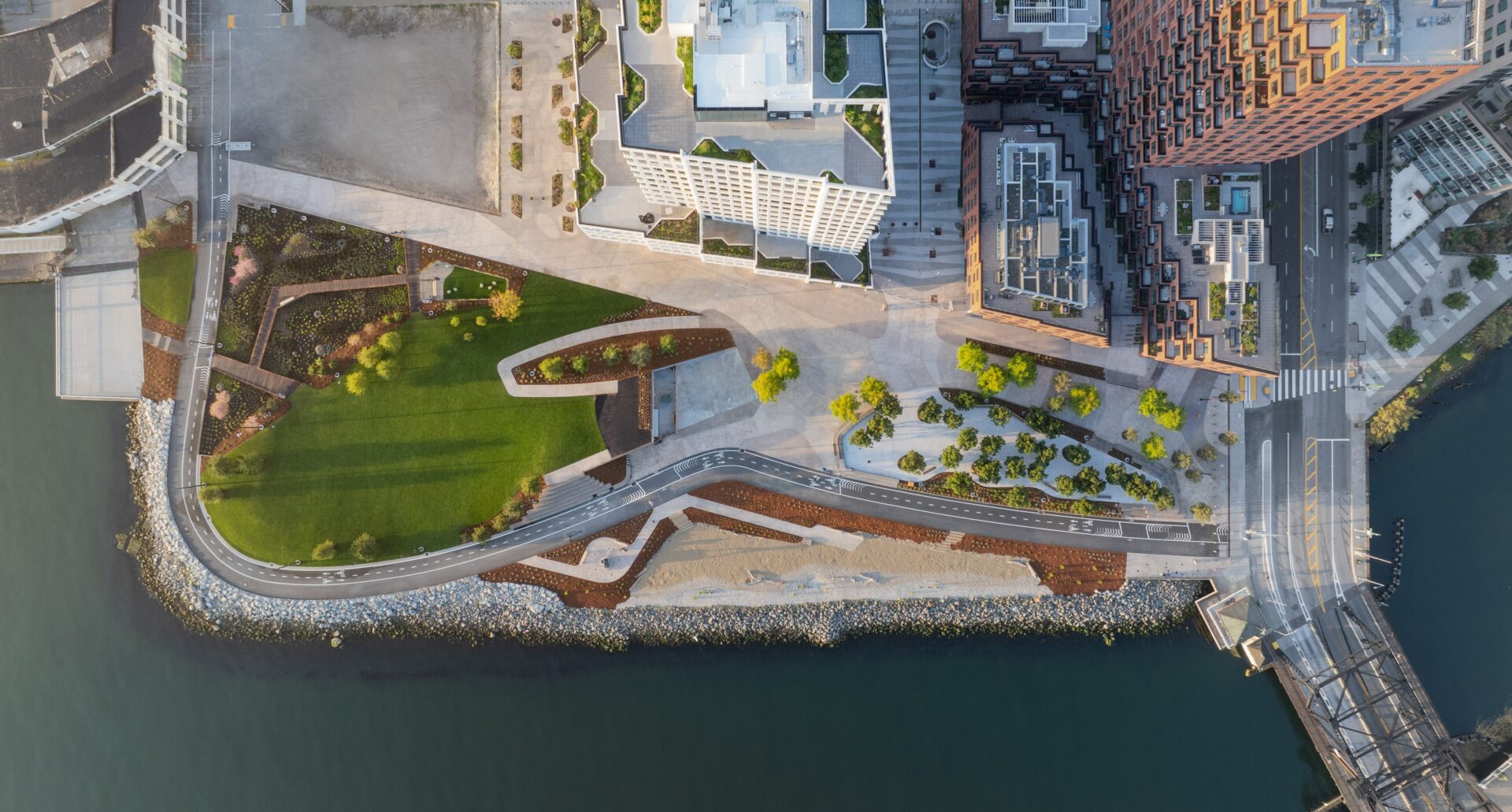

Breaking Ground: Mariposa Creek Parkway

In historic gold rush town Mariposa, their quiet creek is at the center of a local revival. “For so long, Mariposa Creek has been treated as the back of house for downtown,” says WRT principal John Gibbs, “a space you walked past, not into. Our goal is to flip that perception on its head.” Mariposa, just west of the southern tip of Yosemite, has relied heavily on tourism dollars from visitors en route to the park. But with increasing wildfires, floods, and extreme heat threatening park access, the county is looking to develop a more robust trail system of its own, connecting Mariposa to the larger Sierra Nevada and Merced River trail networks. “We want it to be more than just a space for tourists passing through on their way to Yosemite,” says Gibbs. “It’s for the people who live and work here every day.”

Fire is at the heart of the effort – not as a threat, but as a respected partner. “We are doing cultural burning in this project, and it’s different than prescribed burning,” says Ben Goger, senior planner with Mariposa County. Cultural burning, says Goger, isn’t focused on fuels reduction, or the safety of current urban and suburban footprints. Planned in partnership with the Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation “it’s based on cultural revitalization of a really important practice that California landscapes need,” he says. “It’s really focused on healing a lot of those broken bonds that people have had with the landscape and with fire.”

WRT envisions the future of the Mariposa Creek Parkway. Photo: WRT

Here, fire isn’t a means to an end. “We don’t see it as we’re prescribing this as a treatment,” says Goger. “It’s like we’re doing this because this is who we are as humans. Fire is important to us. This land in California needs fire, especially where we’re at.”

Of course, flame can be a tricky brush to paint with. “Fire doesn’t operate on our schedule,” says Gibbs. “A burn can be called off at the last minute because of something as unpredictable as a shifting wind or an inversion layer trapping smoke near the ground. One day might be too damp, the next too dry.” But seeing its renewing power firsthand has been shifting perspectives about land management, both within WRT and in the town of Mariposa. “What’s been truly fascinating is how cultural burning draws people in,” says Gibbs. “There’s something undeniably compelling about seeing fire as restoration, not destruction.”

After about a year of cultural burning and revegetation with native plants, Mariposa has attracted a coalition of new project partners: native animals. “An amazing amount of birds have come back into this area and scattered seeds of native plants” says Goger. “We have beaver back on the site, changing the hydrology and getting the creek working in a more nature-based-solution manner.”

According to Goger, the Parkway project is about halfway to completion but the work of caring for a living landscape is never-ending. “We’ve teed up so many different implementation projects through the planning effort that now we’re like, okay, let’s finance and fund these,” he says. “It’s in the middle of forever.”

Home Stretch: Marin Sea Level Rise Study

A TAM map identifying roads and transportation assets in the Corte Madera area subject to future flood risks. Photo: Mill Valley bike trails and roads frequently flooded during king tides. Photo: Josh Edelson

In April, the Transportation Authority of Marin will wrap up Sea Level Rise Adaptation Planning Study, a proactive planning study funded by Marin’s Measure AA sales tax measure that allots 1% of its revenue toward sea-level rise planning.

The study is well-timed — after the Bay Conservation and Development Commission unanimously adopted its Regional Shoreline Adaptation Plan in December 2024, the pressure shifted to local governments that must now write “subregional” plans for dealing with sea level rise.

“This project has had to be a little bit nimble to adapt to this changing environment,” said Meg Ackerson, a climate adaptation engineer with design company Arup. But Ackerson says the underlying goals of of the study — ”How do we think holistically about sea level rise adaptation in the county? How is TAM evaluating and looking at the transportation infrastructure, the majority of which is coastal in Marin?” — have aligned well with broader regional planning.

One new strategy in the works is: a “voluntary adaptation policy” that makes it easier for existing infrastructure projects to add in adaptation upgrades — elevating roads incrementally, or adding in stormwater drainage features, for example. “Oftentimes there’s already a backlog of maintenance projects — how are we going to cut to the front of the line with a big sea level rise adaptation project?” says Arup engineer Jack Hogan. “Maybe we don’t need to. Maybe we can piggyback onto existing projects that are already in the pipeline, and add on features.”

Ackerson and Hogan hope that local governments working on their subregional RSAPs will take advantage of the study’s ingredients, like the adaptation summaries that outline key challenges, strategies, and opportunities for a number of focus areas like Sausalito, Tam Junction/Marin City, Mill Valley, and Corte Madera/Larkspur.

“It’s not ready to be implemented tomorrow, but it’s at least giving these areas a really great foundation to take it one step further,” says Ackerson.

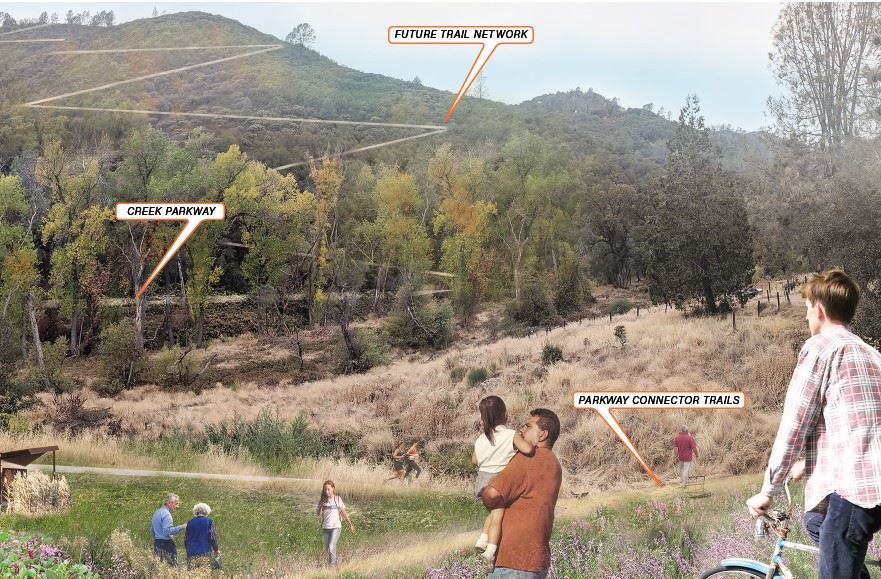

Mission Accomplished: China Basin Park

Past the Bay Trail, China Basin Park drops down to Bay waters. Photo: SCAPE.

A Mission Rock parking lot has recently metamorphosed into one of San Francisco’s newest urban green spaces: China Basin Park, five acres on the waterfront with a view across Mission Bay to Oracle Park, a big lawn, access to shoreline lands, and stormwater garden, all rimmed by the Bay Trail.

The project, a complicated collaboration between Mission Rock, the San Francisco Giants, developer Tishman Speyer, and the Port of San Francisco, faced a typical Bay Area conundrum: how do you build a site up to reduce risk from sea level rise, without making it so heavy that it subsides right back down into the sea? “There are all of these opposing factors that are happening on the site,” says Kaleen Juarez, director and project manager with landscape architecture and urban design studio SCAPE – including connection to the water. “Typically, when we think about reducing risk for sea-level rise, people think, ‘Oh, we have to build everything up.’ The challenge is, how do we do that while still allowing people to access the shoreline?”

The solution is something Juarez calls “a lightweight fill sandwich” (not a technical term, she notes) — a combination of cellular concrete, recycled glass aggregate, and geofoam that’s lighter than the previous landfill. “It’s building the site up in order to make the site lighter,” she says. “It’s 10% lighter than it was before, and it’s 10 feet higher, which is kind of crazy, right?”

The project is targeting 2100 sea level rise. “We started China Basin Park in 2018. It finished in 2024. That’s a long time to think about how quickly sea level rise and climate projections change,” says Juarez. “We’re designing to a future that is changing every single day.”

Alongside rising tides, China Basin must handle a different kind of cyclical flooding: the fluctuations of human usage. “[The park] can accommodate a lot of people on game day. It can accommodate a group of friends playing catch on the lawn. It can accommodate a run club, or just residents from Mission Rock,” Juarez says. “To see that many people ebb and flow through it – it’s particularly compelling to me.”

Other Recent Posts

Assistant Editor Job Announcement

Part time freelance job opening with Bay Area climate resilience magazine.

Training 18 New Community Leaders in a Resilience Hot Spot

A June 7 event minted 18 new community leaders now better-equipped to care for Suisun City and Fairfield through pollution, heat, smoke, and high water.

Mayor Pushes Suisun City To Do Better

Mayor Alma Hernandez has devoted herself to preparing her community for a warming world.

The Path to a Just Transition for Benicia’s Refinery Workers

As Valero prepares to shutter its Benicia oil refinery, 400 jobs hang in the balance. Can California ensure a just transition for fossil fuel workers?

Ecologist Finds Art in Restoring Levees

In Sacramento, an artist-ecologist brings California’s native species to life – through art, and through fish-friendly levee restoration.

New Metrics on Hybrid Gray-Green Levees

UC Santa Cruz research project investigates how horizontal “living levees” can cut flood risk.

Community Editor Job Announcement

Part time freelance job opening with Bay Area climate resilience magazine.

MORE

- Resilience Hub

- To submit your project for possible inclusion in a future column, complete this Google Projects Survey Form

KneeDeep is an independent news magazine and does not endorse any of these consultants, businesses, or projects.