Yell Fire on a Community Network

“We want to get it right the first time because people are making life-safety decisions based on what we post.”

When Sonoma County residents smell smoke, they usually hop on social media or check some alert services like Nixle or PulsePoint to find out what’s going on. The need-to-know response follows the last five years, which for many feels like one long wildfire season — and in some cases, numerous evacuation notices.

During the 2017 North Bay firestorms, most of the region was still getting information about the disaster from televised CalFire updates, usually broadcast once a day. By 2019, another notorious fire year, the information situation improved a little. By then people could check official websites for pixelated maps and set up alerts for services like Nixle, which often sent quickly outdated general alerts. Eventually, fire-affected communities started sharing info in organized groups on social media, like Facebook. But social media isn’t really designed for quickly and accurately sharing disaster alerts.

“On Facebook, you never know where your post is going to end up,” says Sara Paul, a Sonoma County resident and a self-made community fire resource who runs a Facebook group called Sonoma County Fire Updates that has 13,330 followers. Or, the sources available just didn’t provide enough fine-grained and accurate information fast enough, or in a way that was universally accessible. That’s why a group of technologists and community fire experts — including Paul — teamed up to create a new way of organizing and updating communities during disaster.

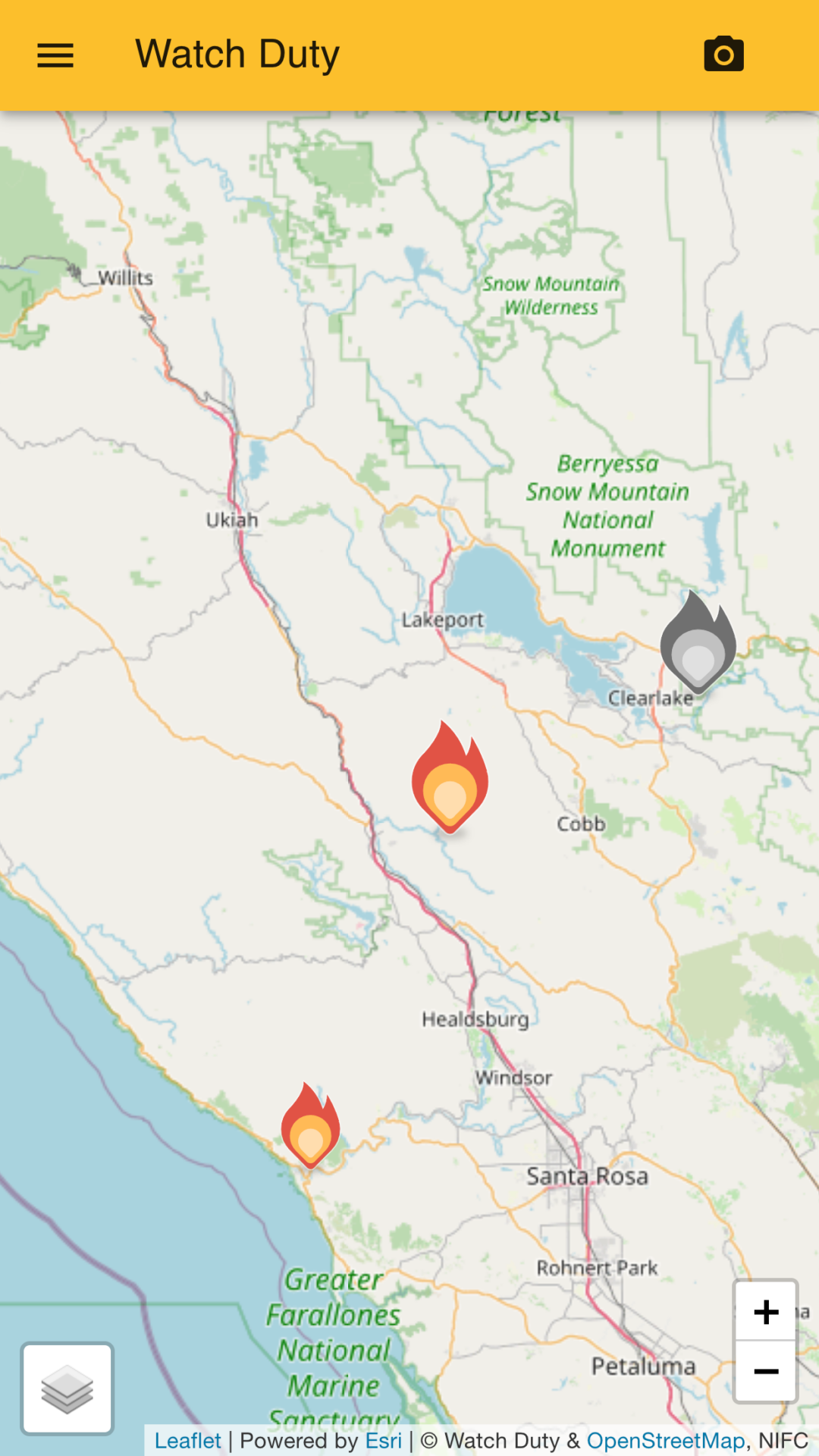

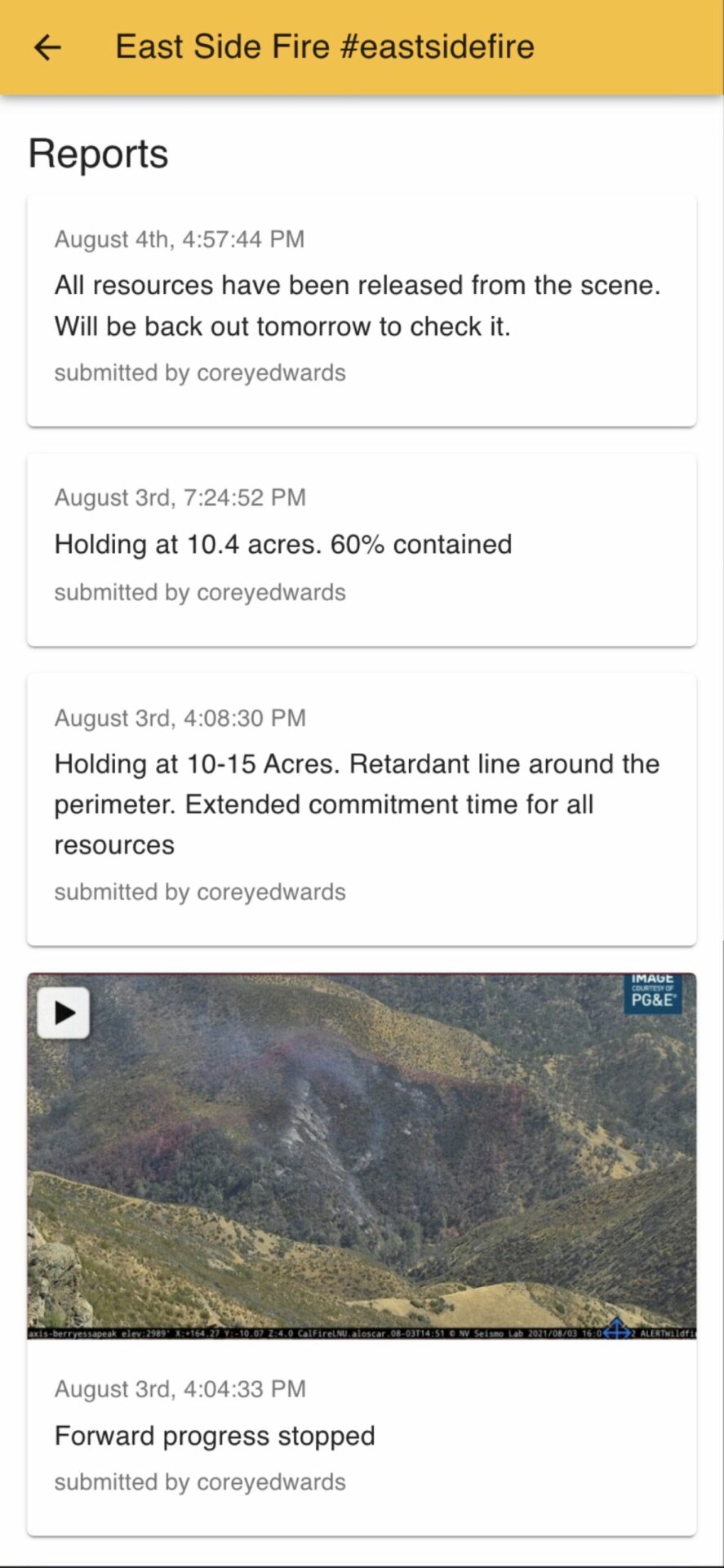

The project, called Watch Duty, launched over the summer and has two parts. The public-facing side is an app available on Apple and Android and via web browsers. The app provides incident notifications and a feed with all relevant information about a fire, from the first reporting all the way through the cycle until the fire is out. The team recently added new functionality in the app that allows community members to submit images and updates. If the crowdsourced info is accurate or adds value, it gets added to the reporting on the incident.

“The idea was: Let’s use community members to help keep other community members safe,” says Lukas Bergstrom, one of Watch Duty’s co-founders who now serves as the head of product on the all-volunteer team. “And let’s give them better technology to do that.”

The way that Watch Duty came to be is like a mashup of a Silicon Valley startup and a grassroots organization leveraging deep local knowledge. It started with John Clarke Mills, a resident of a remote part of Healdsburg who had to evacuate during the 2020 Walbridge fire. Following his experiences and a lack of actionable information during the massive firestorm, Mills, a co-founder of a San Francisco-based tech company supporting retail stores called Zenput, identified the need for something better. This led to the idea for WatchDuty and what Bergstrom — himself a former Google product manager — calls a “community-driven disaster intelligence platform.”

The value of the Watch Duty app comes from the information network assembled on the back end. Rather than just aggregating info that comes from official channels, Watch Duty has created an integrated system of news gathering. “My information comes from a fire scanner, wildfire cameras, CalFire aircraft flight paths, satellite data hotspots, and daily briefings from CalFire,” says Paul, who is now one of a handful of Watch Duty’s citizen information officers (CIOs).

In addition to Paul, there are currently two more CIOs in Sonoma, two in Lake County, three in Mendocino County, and one in Napa County. All of the CIOs were somehow involved with fire reporting — mostly on social media — before joining Watch Duty. And many, like Watch Duty’s founders, have been impacted in some way by Northern California’s increasingly damaging and deadly wildfires.

The team works collaboratively during incidents to fact-check and confirm information. They are also looking to add more CIOs and cover more of California, but finding the right people takes time. “There’s not a huge community of people doing this,” says Paul. “Which, given California’s recent fire history, is kind of surprising.”

When a wildfire incident breaks out anywhere in the regions they cover, CIOs check their various sources for information. And then they confirm the incident details they have gathered independently. “We have a very active message board for every incident,” Paul says. “We verify information before we take it live, and make sure it is a real fire, not just something that someone else has put out there,” Paul says. “We want to get it right the first time because people are making life-safety decisions based on what we post.”

A Watch Duty alert from the Napa Valley warned a property owner sitting on his porch in Calistoga of a fire on one of his other properties 10 miles south on Mount Veeder. A delivery van had dropped a package by the gate, but failed to turnaround properly, spinning wheels and causing a fire in the dry woods. The alert convinced the property owner of the value of the network. The delivery van was toast. Photo: Jim Munk

If you’ve lived through a disaster, like a fire-forced evacuation, then you understand that following the news and making decisions becomes all-consuming. Before, says Guerneville resident and Watch Duty user Jennifer Zapp, when a fire broke out anywhere nearby it would be stressful, because of the speed and intensity with which recent fires have moved. “Watch Duty took away the anxiety of not knowing what’s going on, and having to rely on Facebook,” she says. “Now I get a notification and I get info from start to finish. That matters more than I think we realize.”

Zapp grew up in Guerneville, a community that because of its position astride the Russian River has seen its fair share of disasters. She remembers people gathering at Pat’s International, a restaurant on Main Street, when the town flooded in the past. “People would literally canoe into Pat’s,” Zapp says, “They had a generator, and food, and a bar. We would gather there to find out what was going on, and who needed help. It was a place to come together and get accurate information about what was going on in the community.”

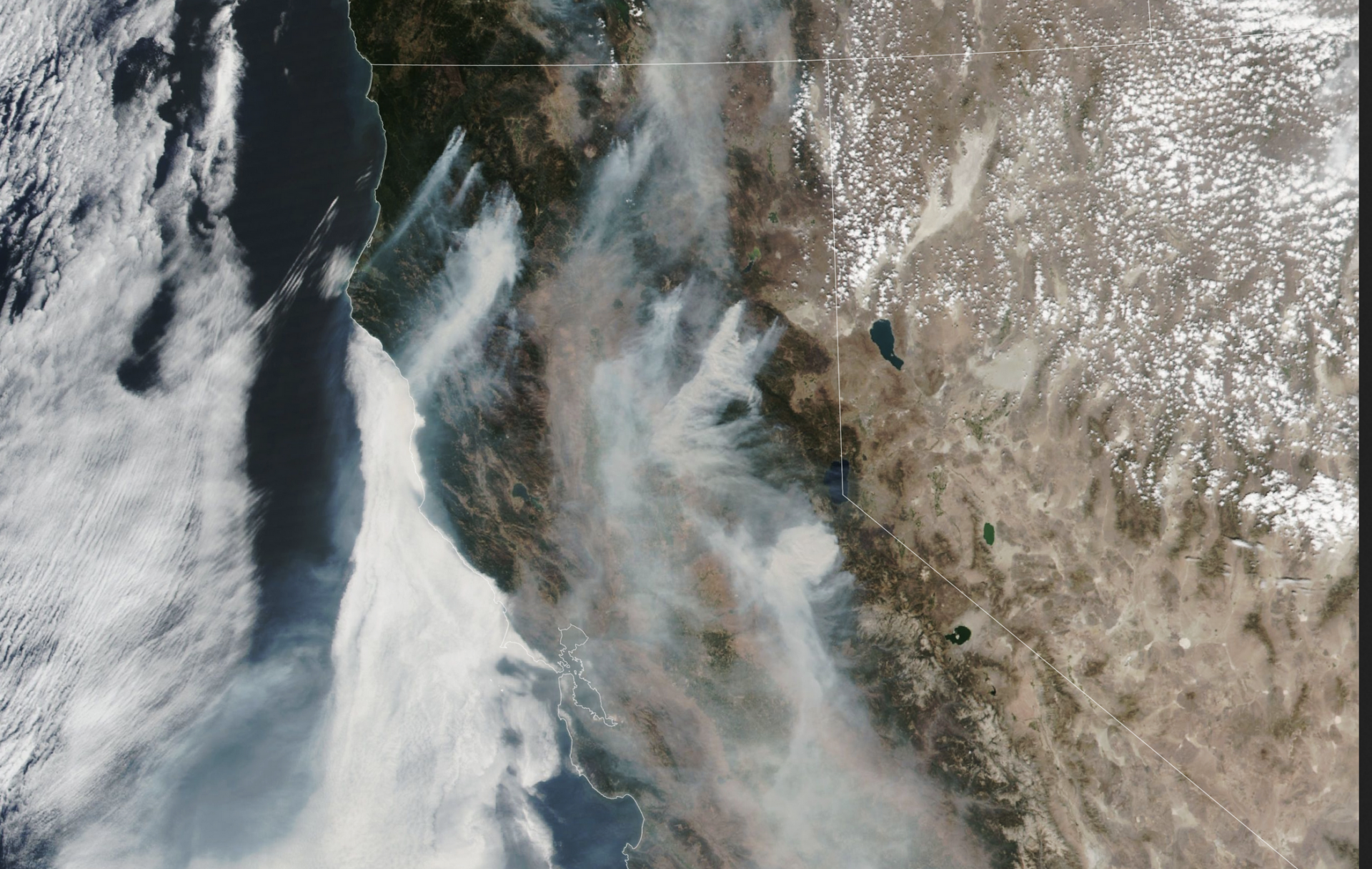

Peak of California’s fire season this August 2021; smoke travelled all the way across the country. Photo: NASA Earth Observatory.

In a lot of ways, that’s exactly what Watch Duty is trying to do. And while the app is a user-friendly way to display updates, the utility of the service is really only as good as the level of trust that people feel about the information they are getting. Even during its brief existence so far, Zapp says she has seen Watch Duty CIOs make changes in the way and frequency that they share information and to try to make what they are reporting better. “It doesn’t feel knee-jerk,” says Zapp, “They are people in our community and these fires can be affecting them too. It feels community-based and community-grown, and like it’s a trustworthy situation. They are invested in making sure the information is right.”

One thing is sure. As the climate becomes more erratic, there will be more natural disasters in the future. Not just in Sonoma County and the broader region, but everywhere. “We are watching this space,” Bergstrom says about community disaster reporting. “There is a lot more we want to do, like to expand geographically and to cover other types of extreme-weather events, but that will take resources.”

Meanwhile, we’re all getting accustomed to keeping a weathered eye out. “We’ve kind of become storm chasers of sorts, because of all of these disasters,” says Zapp. “Now we can be prepared and make better decisions.”