Will PG&E’s New Rates Help More People Electrify Their Homes?

“A middle-income earner should not be paying the same fixed rate as Elon Musk.”

When Jason Clock added a solar array to the roof of the mobile home he shares with his mom in Mountain View a few years ago, he bought a single electric stovetop burner, but kept his gas stove as well. Clock, who works remotely as a Product Manager for Georgetown University, wants to make the greenest choices possible within his budget. But with nine more years before he breaks even on his solar panels, he can’t afford to go all-electric yet.

Soon, thanks to a recent vote by the California Public Utilities Commission, changes to his utility bill could encourage him to finally get rid of gas altogether. Or that’s the idea. Instead of simply charging him for every unit of electricity he uses, beginning in early 2026, PG&E will charge Clock and other Californians a $24.15 flat rate and a lower usage rate per kilowatt-hour.

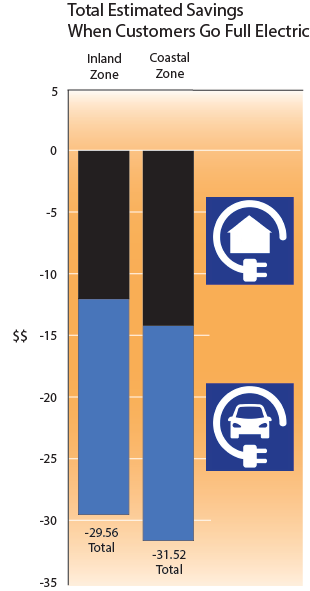

After reading through the modeling CPUC did when it proposed the new fixed charge earlier this Spring, Clock was surprised to learn that he might actually save money if he uses more electricity by adding a heat pump and other appliances. “[It says] that even though the electricity demand will be higher, our total utility bill will be $27 lower? I am finding that hard to believe,” he says.

Bill savings for PG&E customers in a home electrification scenario. Source: CPUC

Clock’s skepticism may be warranted. Until he goes fully electric, he may actually be paying more based on his location in a temperate zone where he uses less energy overall. But he also understands that keeping his gas appliances won’t make sense either as more homes electrify and gas prices go up as a result.

Clock’s conundrum isn’t unique. Those who can’t easily afford to make the switch to electric, but make more than the bare minimum, may end up feeling like they’re paying an unfair portion of the cost of the energy transition thanks to the income-generated fixed charge or IGFC.

The new rate package is coming down the pike at a moment when state and local rebates and incentives have allowed a growing number of Bay Area residents to replace their furnaces, hot water heaters, and other appliances with electric appliances that can make use of the solar, wind, and geothermal power produced in the region. The effort to electrify homes is central to regional and state-level plans to simultaneously reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve air quality.

Over the next two years, multiple levers — including the new rules put in place by the Bay Area Air Quality Management District and the upcoming Equitable Building Decarbonization Program, which will expand on existing efforts to install electric appliances directly in low-income homes — could usher in a new era.

At the same time, because of the way the CPUC has set the charges, experts say the new fixed rates could burden lower-income people while preventing the wealthiest Californians from paying their fair share.

How Income Plays a Role in Your New Bill

Gavin Newsom signed AB205 — the bill responsible for the incoming electricity-rate changes in 2022, based on a 2021 study by the Energy Institute at the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley. It suggested protecting low-income ratepayers from some of the cost of making California’s grid resistant to wildfires and adaptable to renewable energy.

AB205 is very specific with its target beneficiaries, however. It’s designed to help low-income ratepayers with average electricity consumption save money on their bills without “any change to usage.” The CPUC was tasked with determining what that would look like in reality.

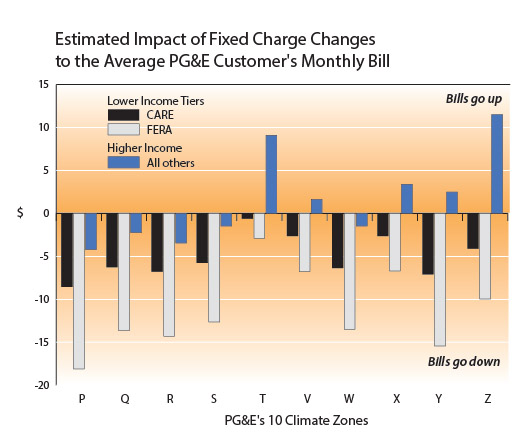

The agency’s modeling suggests that under the new plan, substituting electricity for gas will benefit most customers financially and the agency has said that all customers will save 5-7 cents for every kilowatt hour. According to Sylvie Ashford, an analyst at the Utility Reform Network, “That doesn’t translate to a decrease in the electric portion of the bill, but it does mean a decrease in overall spending.”

Photo: Ariel Okamoto

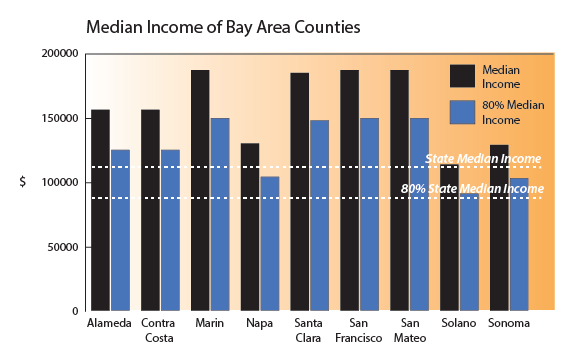

According to CPUC President Alice Reynolds, the IGFC “lowers overall electricity bills on average for lower-income households and those living in regions most impacted by extreme weather events.” And it does offer a six-dollar fixed charge for customers who are already eligible for the California Alternative Rate Electrification (CARE) and a $12 flat fee for the Family Electrification Rate Assistance (FERA). But it turns out those programs are based on limited definitions that don’t apply to everyone struggling to pay their bills.

As Jordyn Bishop, senior legal counsel of energy equity for the Greenlining Institute, explained, “Those programs are based on federal poverty guidelines and that is not reflective of what it means to be a low-income household in a state like California, with high cost of living variations.”

Although the CPUC considered a four-tiered system, it ultimately ended up setting just two low-income fixed rates — and another for everyone else. The commission chose not to define the moderate-income customer, a classification that would have helped to create a truly income-graduated fixed charge.

Missed Opportunities for a More Equitable Fixed Charge

Though the California Environmental Justice Alliance (CEJA), a coalition of environmental justice groups across the state, proposed that the CPUC create a system with five tiers in an effort to create a graduated set of charges, the agency stopped at three and created a working group to design a more progressive IGFC in the future.

In addition to guidelines that took Bay Area costs of living into account, CEJA was also pushing for a higher fixed charge for the wealthiest Californians: those who can most easily afford to electrify their homes, put solar panels on their roofs, and plug in EVs. Greenlining Institute was also pushing for a higher charge for those households.

“Without that — with the structure that the CPUC adopted — it’s fair [to say] that right now the folks in the middle are going to be picking up the tab,” says Bishop. “Mandating that someone whose household income falls just outside of the CARE and FERA eligibility limits pays the same fixed charge as millionaires in our state is not an equitable structure.”

Shana Lazarow, legal director at Communities for a Better Environment, a CEJA member organization, agrees. “A middle-income earner should not be paying the same fixed charge as Elon Musk,” she says. CEJA had also petitioned for a zero-dollar flat rate for low-income folks, who it says are struggling to keep up with energy costs and rent burdens across the state.

As Bishop explained, “Black and Brown households hold a substantially higher energy burden. We know that low-income communities of color are more likely to live in formerly redlined communities and the housing stock in these communities are generally much less energy efficient.”

Meanwhile Clock and other ratepayers stuck in the middle could see bill increases as high as $11.26 a month. And according to CEJA, low-income earners who don’t qualify for CARE or FERA and don’t live in areas facing extreme weather variations may see bill increases unless they go all-electric.

Yet PG&E and the two other large electricity providers in the state have said providing more tiers would be too complex. “Each of these proposals would require a new income verification process that would take significant time and resources to develop and implement,” the CPUC said in its proposal, in response to CEJA and Sierra Club’s pitch. CPUC didn’t respond to direct questions from KneeDeep Times, and instead pointed to its press release on the final IGFC.

“Right now, this is frankly just a fixed charge that charges some money to very low-income people and more money to everybody else,” Lazarow says. “That’s not income-graduated, that’s just a fixed charge.”

The Greenlining Institute will continue to advocate for more tiers in the CPUC’s rate system, Bishop says. “We’re hopeful that these working groups will lead to a more equitable fixed-charge structure in the future.”

Big Utilities Still Prevail

The CPUC’s limited definition of low-income and its decision to not define “moderate-income” at all, has made its interpretation of AB205 controversial among Congress and environmental justice groups, which worry that the IGFC doesn’t adequately incentivize conservation.

As all this plays out, there’s also the looming question of what it might take to get the big energy companies to pay for at least some of the cost of the transition themselves. Jillian Du of the Bay Area Regional Energy Network (BayREN) is working on transforming the agency’s home-electrification efforts to meet the needs of those who don’t quite qualify for low-income electric appliance installation programs, but don’t have much to spare either.

Du believes the question of who can electrify their homes at this moment is intricately tied to the market dominance that the three large corporate utility companies have in the California marketplace. “It’s a result of a social contract that we don’t necessarily need to be in,” she says. “Right now, the assumption is that ratepayers pay for everything. We’re going to pay for the investor-owned utilities to make their aging infrastructure more resilient to wildfires. We’re also going to assume that ratepayers pay for some of this transition off gas infrastructure. This assumption is causing a lot of this tension, and it doesn’t have to be that way.”

Du pointed to the growing energy democracy movement, as exemplified in the rise of local community choice aggregators, as slowly building alternatives — “[even] it’s going to be a decades-long process to disentangle ourselves from the current system.”

Twilight Greenaway contributed reporting to this article.

MORE

- An Explainer on California’s Income-Graduated Fixed Charge Debate, UCLA Law’s Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment