A look inside Marin County’s slow-moving response to an urgent local and regional need for affordable housing.

A rack of clothing hangs outside the entrance to the Finders’ Keepers’ Shop, located on the first floor of Golden Gate Village, a public housing development in Marin City, California. “It looks just like you are going into a little tiny hole-in-the-wall boutique,” says Royce McLemore, who has lived at Golden Gate Village for the last 48 years.

Inside, there’s a Black Lives Matter sign hanging above the check-out desk, and the shelves are lined with household appliances, bedsheets, and gently worn pants and t-shirts. Everything here is free, McLemore tells me, her voice firm with pride.

The shop is one of several projects run by Women Helping All People, an organization McLemore co-founded in 1990 with the mission of supporting the low-income and underprivileged residents of Marin County. “My purpose is to stand in the gap,” she says. In its early days, the shop was bare bones, just a few racks of clothing that a group of women would set up on their patio and distribute to residents twice a week. Now the store, alongside the organization, has outgrown its backyard beginnings. Across the driveway from the shop, Women Helping All People has an office space, where McLemore, age 81, continues her work. The organization also runs educational services, workforce training, and family counseling.

Today, the Finders’ Keepers’ Shop stands as a testament to the Black residents of Marin City’s resilience, persisting despite the county-wide gentrification that has threatened to displace much of the community.

“We are experiencing an extreme housing crisis here,” says Jenny Silva, board chair of Marin Environmental Housing Collaborative. Across Marin, affordable housing for low- and middle-income residents is scarce. “We priced out the nurses and teachers long ago,” Silva says. Nowadays Marin even struggles to recruit doctors given the very high cost of housing, she notes. The median Marin home costs $1.7 million — a price only affordable to the richest 1%. As a result, 70% of Marin’s workforce is forced to live outside the county.

As Marin’s housing crisis intensifies, so do the climate risks throughout the county — a dual crisis that has sparked a contentious debate over where and how to develop new housing. Some advocates are pushing for more affordable housing to support the residents who are being priced out. However, local opposition over environmental, flooding, and safety concerns has hindered development.

In this complex landscape, Marin City, a small unincorporated community just across the bay from San Francisco, illustrates the effects of years of gentrification throughout the county. Although less than 2% of Marin’s residents live in Marin City, it accounts for 60% of the county’s affordable housing units. Marin County is regarded as the most racially segregated county in California.

Black residents make up nearly a quarter of Marin City’s population, compared to just 3% of the county as a whole, a number that is shrinking as rents rise and Black families are continually priced out. Many residents believe they have been deliberately neglected by the County, denied adequate infrastructure, and plagued with a myriad of environmental and public health issues. “They are trying to force us out,” McLemore says.

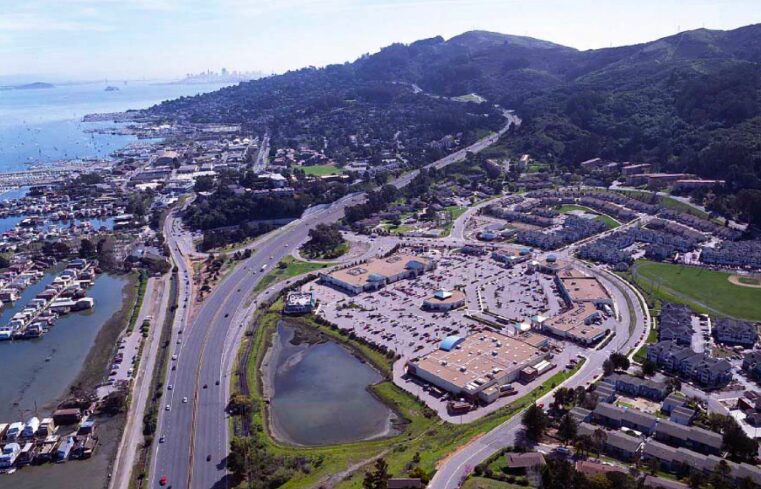

Marin City climbs the hill and surrounds Golden Gate Village and its parking lots on the west (right) side of Highway 101. Approaches often flood. Photo courtesy Marin County Flood Control District.

The county of Marin is marked by many extremes — extreme beauty, extreme costs, and more recently, an extreme climate. Despite its proximity to one of the world’s largest economies, much of the county has been spared from development, with over 50% of Marin’s land protected and preserved. That vast, open green space is the reason many people are drawn to living there — and also a common justification for curtailing any new development.

But Marin’s landscape — the long coastlines and remaining old-growth forests — also makes existing development particularly vulnerable to climate change. At Marin’s western edge, Highway 1 traces the golden bluffs that overhang the Pacific. As sea levels rise, the cliffs are slowly eroding. In the Mount Tamalpais foothills, where homes were built among verdant redwoods, the threat of wildfire looms. In the surrounding coastal hills, heavy rainfall flows down steep, rugged terrain, heightening the risk of landslides. And along the Bayshore, high tides and storm surges regularly flood low-lying areas. “We are totally in harm’s way,” says Douglas Wallace, a Marin County resident who sits on the Tam Design Review Board.

To some, the answer to Marin’s housing crisis is clear: build more housing. But high development costs, looming climate risks, and fierce local opposition have stalled progress. Marin is not unique in its struggle for housing — counties across the state and country are facing a housing crisis — but Marin has been particularly slow to respond. Since 1969, Marin’s population has only grown from 203,506 to 256,018, and housing production remains the lowest in the greater Bay Area. As both the housing and climate crises intensify, residents are fiercely divided about what just and equitable housing development should look like in Marin County.

One Project Stutters Ahead

In 2020, the Marin County Community Development Agency approved a proposal to build a five-story, 74-unit affordable housing project on 825 Drake Avenue in Marin City, located down the street from Golden Gate Village. Originally, the site was zoned for only 40 units. However, when the developers, Pacific West Communities, wanted to increase the capacity to 74 units, the county had to approve it. This approval was facilitated by state law SB 35, designed to streamline housing construction in counties and cities like Marin that have not met mandated housing requirements. Under SB 35, developments that meet specific affordability standards can move more quickly through the review process, explains Sarah Jones, the Marin County community development director.

“Affordable is not affordable, and as a resident of Marin City, I learned this the hard way,” McLemore says. Developers like Pacific West Communities have been building “affordable” housing in Marin City since the 70s, she explains. It’s developments like these that have been the impetus for an “onslaught of gentrification,” which has forced many Black people to lose their homes. Rather than providing new or better housing that is affordable to those displaced, the developments are sold to higher bidders — new residents with deeper pockets. “It’s the old one-two [punch] story,” McLemore says, knowingly.

Proposed new housing development at 825 Drake. Rendering: AMG

“There was a lot of community pushback and concern,” Jones says. Save Our City, a coalition of Marin City residents that formed in opposition to the project, claims that 825 Drake represents the latest chapter in a long history of inequity and disregard for the community’s interests — issues that have characterized the relationship between Marin City and Marin County for decades. They say that the development will block sunlight to seniors living in the Village Oduduwa complex next door, decrease the amount of parking available to residents, and impede the access of emergency vehicles into the complex and adjacent streets.

“[825 Drake] is putting more affordable housing where affordable housing already exists. If we are concerned with desegregating our communities, we should be putting affordable housing in higher-cost areas,” says Leah Rothstein, an affordable housing consultant and the author of Just Action: How to Challenge Segregation Enacted Under the Color of Law.

The proposed development is also located in an area that has been designated as having high fire risk, according to a recently updated assessment by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. “There’s one road in and one road out,” says Amy Kalish, a Mill Valley resident who runs Citizen Marin, a website that hosts resources for Marin County residents to learn about and challenge California housing policy. “[The residents] are really impinged.” Residents have expressed concern that in the event of an evacuation, additional cars could cause congestion on the roads — a fear that is echoed by residents living in high-fire-risk regions across the county where development is under consideration.

The risk of wildfire in Marin City was not severe enough to warrant not approving the project, Jones, the county’s community development director, tells me. “It is comparatively a lower risk and in a more accessible location when it comes to fire than many others in Marin County,” she explains.

Map of flood risk and sea level rise in the Marin City area. Map: Marin City Health and Climate Justice

Negotiations with the county, however, resulted in the developer purchasing a new site at 150 Shoreline Highway in Tam Junction, where they agreed to relocate 32 of the 74 units intended for Drake Avenue. The new site is situated along the Bayshore, at the intersection of the 101 and the Pacific Coast Highway. “It’s a poster child for flooding,” Wallace says. He recently visited the site during a king tide to find the area totally submerged. Wallace points out that the restaurant next door to the site, called Floodwater, has its name for a reason.

“They’re basically moving units from a fire hazard area into a really active flooding area that’s susceptible to sea level rise,” Kalish says.

Other residents, concerned about the site, expressed fears that it would also increase traffic in an already highly congested area. “There’s no reason for this kind of density to be in an area that can’t support it,” Kalish says. She believes that there are better options, closer to jobs and infrastructure, with less environmental risk. Sometime soon the county Board of Supervisors will consider rezoning the site in Tam Junction to accommodate the developers’ plans.

Chicken Littles in Force

Susan Kirsch — who lives four miles north of Marin City — does not believe drastic new development is the answer to the housing affordability crisis, particularly amid a changing climate. “I just see such an urgency with the threats to the environment,” says Kirsch, who is a self-described “midwife to people waking up and taking action for protecting our communities.” Kirsch lives in what she describes as a “bungalow” on a tree-lined road in Mill Valley, where she’s lived since 1979. A former professor, she has dedicated her retirement to fighting development that would “diminish safety” and disrupt Marin’s natural environment.

Kirsch grew up on a farm in Minnesota, where she lived in close harmony with her surrounding environment. Her family life followed the seasons — preparing the soil, planting seeds, then growing, nurturing, and harvesting crops. At the end of the season, a quiet time would settle in, where she could reflect on what happened that year, she tells me, with an air of nostalgia. She’s always longed for a similar life in Marin, one lived in close connection with nature. Kirsch speaks with calm passion about “the power of sun, wind, rain, and growth.” Yet she is undeniably fierce — all gas, no breaks. In the last 15 years, she has co-founded six different organizations promoting “slow growth” in California and has successfully challenged several proposed local developments. Recently, she’s turned her attention to statewide issues. Through her organization, Catalysts for Local Control, she advocates for the rights of local communities across California to have more say over what gets built within their jurisdiction.

An unwelcome sight to many Marin County residents, the conversion of small “affordable” homes into bigger luxury homes, obscuring bucolic treelines, replacing permeable acreage with hard infrastructure, and changing the character of neighborhoods. Photos: Susan Kirsch

Many proponents of affordable housing development believe people like Kirsch are to blame for the affordability crisis. “Absolutely, they’re part of the problem,” says housing advocate Silva. These “NIMBYs” (an acronym for “Not in my backyard”) are “really effective” and “willing to dedicate a kind of shocking amount of time,” she says. While they may not be the majority, they are among the loudest and most engaged, giving them an outsized influence, Silva explains.

In response to rising homelessness rates, which have reached record highs in recent years, Kirsch says many Californians and state officials have erupted into “Chicken Littles,” crying “The sky is falling! The sky is falling!” in fear of what “they call the housing shortage.” She believes these fears are unfounded. The issue isn’t a lack of housing, she laments. It’s a lack of truly affordable housing.

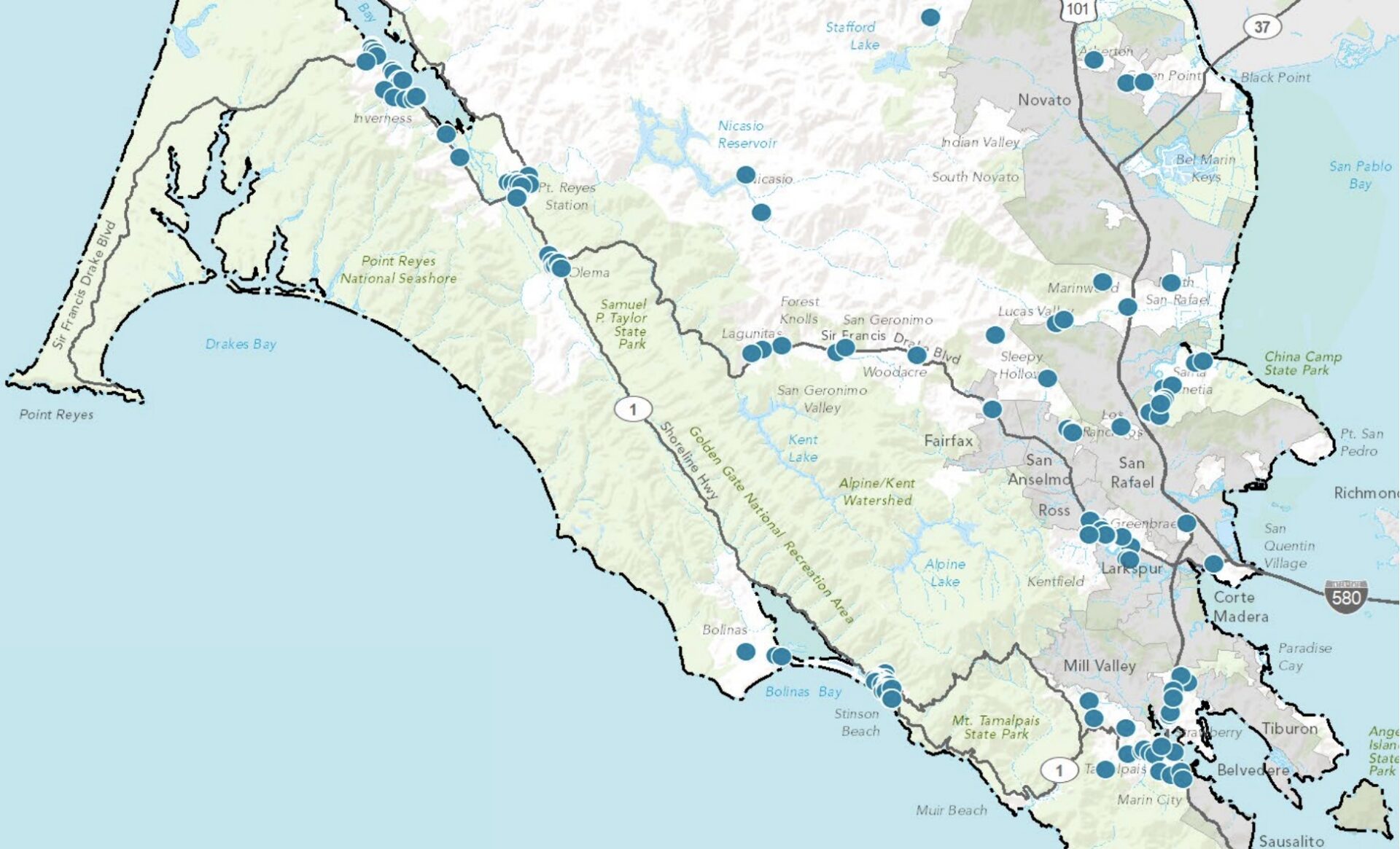

Candidate housing sites safe from fire and flood zones identified in the an update of Marin County Housing & Safety Elements in 2022. Map: Marin County Development Agency

Every eight years, the California Department of Housing and Community Development determines the predicted number of housing units needed by cities across the state, known as the Regional Housing Needs Assessment. The HCD says California is short 2.5 million housing units, 441,000 of which have been allocated to the Bay Area — numbers that Kirsch believes are a gross overallocation. In 2021, Marin’s RHNA increased from 2,298 to 14,405 needed units, a target that the county is nowhere near achieving. While the law is intended to create more affordable housing, many say this is not the reality.

“What communities are getting is just more and more market-rate and above-market-rate housing. So, it makes no sense in that clamor for affordable housing,” Kirsch says. “It’s preposterous, really.” RHNA’s standard for what is deemed “affordable” is based on county median income levels. Due to Marin’s relatively high-income levels, the low-income category in Marin starts at $104,000 for a single person. In Marin City, where the median income is $45,309, even housing projects labeled as “low-income” remain unaffordable for most residents. “Affordable has become one of those awful, misused words,” Kirsch adds.

While Kirsch is in support of developing more truly low-income housing, as well as preserving the low-income housing that already exists, others argue that Marin needs more housing for all income levels — a goal that they say can only be achieved with increased pressure from the state. It’s not just low-income people who are being pushed out; middle-income families are, too, the author Rothstein points out. “We need to start to allow a more diverse housing range to be built there that includes some affordable units, but also includes just smaller [multi-family] units that are affordable to middle-income families,” she says.

Many workers commute to Marin County jobs from the East Bay, where housing is cheaper. Photo: Fix37Now

When asked about Kirsch’s vision for “slow growth,” Silva explains that slow growth is all Marin County knows. “We have achieved the slow growth vision. And what that looks like is you have huge rates of displacement,” she says. “Two-thirds of our workforce have to commute in, and a quarter of the population is at risk of being displaced if they lose their housing for any reason.” She says the traffic that residents complain about isn’t a result of density, it’s because the workforce is unable to afford to live in the community and is forced to commute, in addition to a recent reduction in the number of school buses. “We’re contributing to greenhouse gasses. We’re contributing to the sprawl,” Silva says. She believes Marin can do better.

Standing Their Ground

Kirsch’s “slow growth” point of view is representative of what Rothstein describes as “old-school” environmentalism. “There is a long history of environmentalists opposing affordable housing,” she says. Concurrently, the environmental justice movement — which supports investments in lower-income communities — has a history of fighting the placement of environmentally harmful land uses, which are more often located near low-income, segregated communities, Rothstein adds. Climate hazards now need to be considered as well, she explains. But Rothstein is clear in her point of view: “Using [climate] as an excuse to not build where people already live is [just reinforcing] that history of using environmental arguments to continue to deprive low-income areas of resources,” she says. “We have to continue to build housing because we’re in an affordable housing crisis.” Every county needs to do its share to meet regional needs, as established under the RHNA, she says.

Marin County has a difficult balance to strike between ensuring climate resilience and responding to the community’s housing needs. It’s not a hardline — we’ll always say “no” to developing in areas at risk of climate hazards, says Silva, who has explicitly opposed 825 Drake, but is still reviewing the risks and trade-offs of the Tam Junction site. “For existing development along shorelines, you need to figure out how you’re going to protect them, or you need to retreat from them,” she says. If protection is the goal, she believes development could make sense, as it can bring resources that could be used to safeguard the area. Jones adds that the strategies needed to protect existing developments could also support new housing projects.

Flooding at Tam Junction on the Shoreline Highway near the proposed second affordable housing development site. Photo: Ted Barone

Dana Brechwald, assistant planning director for climate adaptation at the Bay Conservation and Development Commission, which recently issued a new Regional Shoreline Adaptation Plan for cities in the Bay, stressed that addressing housing needs without factoring in future climate risks is a short-sighted approach. “It doesn’t matter how much new housing you build if it’s all going to be underwater in 50 years. So, I think it’s in the best interest of the long-term safety of residents and the long-term housing capacity to not use the need for housing as an excuse to not consider what hazards it’s going to be facing in the future,” Brechwald says. It needs to be taken on a “case by case basis,” she says. “I don’t think there’s an easy answer here.”

In Marin City, McLemore is committed to standing her ground. “It’s been a fight from the inception,” she says. Though construction is slated to begin this fall, McLemore believes that ultimately, her community will prevail, and 825 Drake Avenue won’t be built. On October 2nd, a group of demonstrators gathered at the site, carrying signs reading “Save Our City” and “No Sunlight, No Safety” to voice their opposition. Two weeks later, Save Our City celebrated a victory when a Marin County Superior Court judge ruled in their favor, invalidating $40 million in tax-free bond revenue for the development, which they hope will derail the project.

Instead of new, quasi-affordable housing, McLemore advocates for reinvesting in neglected low-income housing infrastructure, as well as converting existing developments to make them affordable for low-income residents in Marin City. “There are people from Marin City who would love to move back here,” she says. Money remains the biggest barrier. “We just need God to send us that angel that would want to do the right thing,” she tells me. Regarding the 825 Drake site, McLemore adds, “Marin City doesn’t have any open space anymore.” She envisions the site becoming a park, something the community could actually benefit from.

Marin City resident Carl Dedrick summed up his memories of flooding and hopes for the future at a November press conference. Video: Sonya Bennett-Brandt

In other parts of the county, there are potential sites for affordable housing that could garner broader community support. In San Rafael, for example, Kalish points to several vacant industrial sites near public transit and existing infrastructure that could be ideal for affordable housing. “For some reason, those areas are not being talked about,” she says. At the site of the former Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary campus near the Strawberry neighborhood, North Coast Land Holdings aims to reconstruct and expand the campus to develop residential units, a portion of which would be affordable. “It looks like a ray of wonderful bright light addressing the need,” Wallace says about the project.