Vote Cinches Robust Regional Response to Sea Level Rise

On December 5, a sprint was over; a marathon began. The Bay Conservation and Development Commission unanimously adopted its Regional Shoreline Adaptation Plan, meeting a state deadline and shifting the pressure to local governments that must now write “subregional” plans for dealing with sea level rise. These are due at the end of 2033: a distant due date in the face of global change, but maybe a quick one considering the complexity of the task.

After RSAP’s first release in September, there was push and there was pull. Local governments and others objected to some of the mandatory standards proposed, calling for “flexibility.” A November draft tacked in that direction, changing quite a few “musts” to “shoulds” and demoting some of the Standards to “planning tips.” Now it was the turn of the environmental coalition, some forty groups, to decry a “watering-down.” Further redrafting ensued.

The result of these contending pressures seems, surprisingly, to please nearly everyone nearly well enough. “We seem to have found the sweet spot,” says BCDC planning director Jessica Fain. The Sierra Club’s Gita Dev agrees: “We are very happy with the results of the RSAP. Now,” she goes on, “it’s time to get serious about execution.”

Local governments are clamoring for support for this new task. BCDC is devising a technical assistance program. With passage of November’s Proposition 4, the Ocean Protection Council will have more funds to grant. To ease the burden and clarify the options, counties and cities around the Bay are looking at doing combined, multi-jurisdictional shoreline plans.

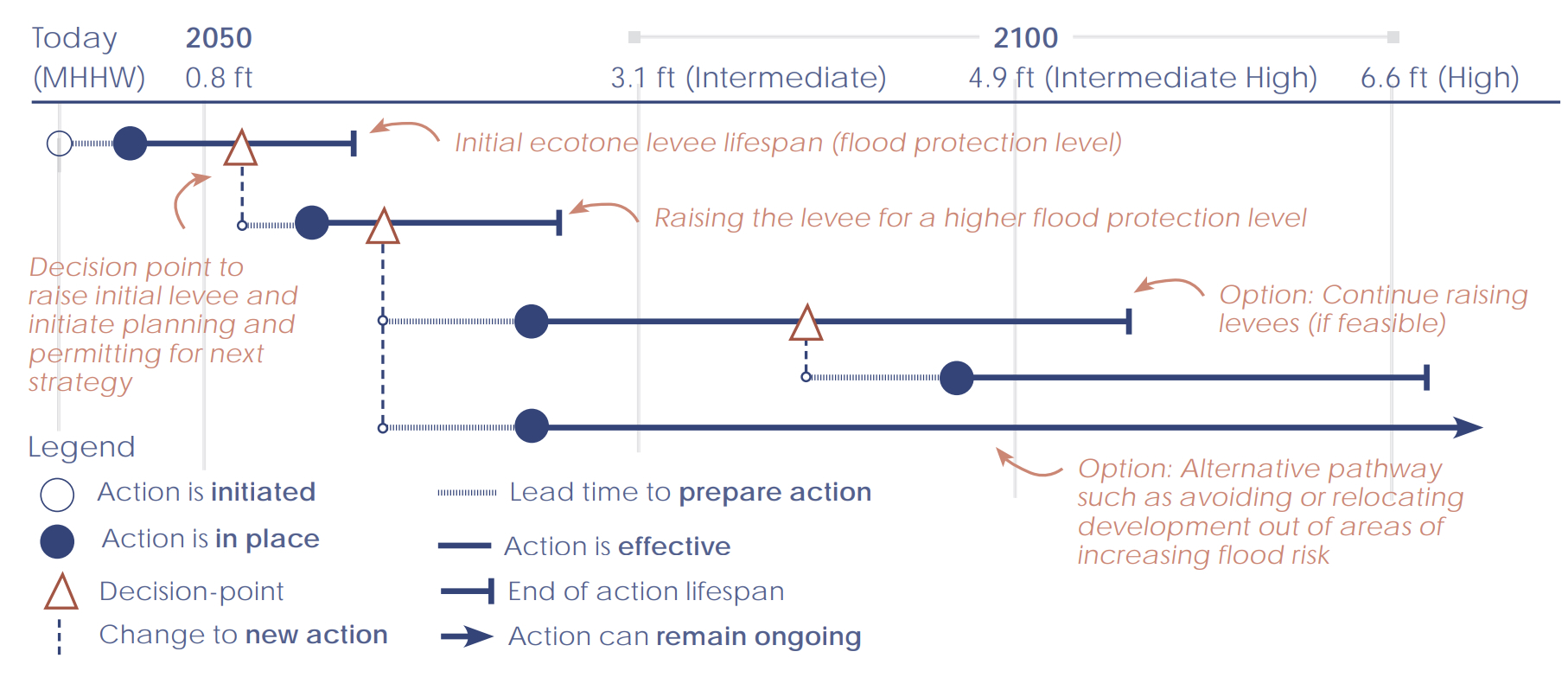

Diagram of how adaptation pathways can unfold. From Werners et al, Environmental Science & Policy

BCDC is also pondering another trip to Sacramento. Under last year’s SB 272, which started this planning ball rolling, the agency can only advise about the plans being prepared — until the moment when they are completed. Then the bay regulators can say “Yes” or “No,” but the sole result of a “No” is that a city or county drops down the priority list for state funding. “The Legislature has taken us halfway,” BCDC executive director Larry Goldzband remarked last summer. Should the agency now seek a stronger hand? “We are planning to lean into that question in 2025,” says Fain.

Top Photo: King tide in Alameda in November 2024 by Maurice Ramirez

Other Recent Posts

CEQA Reforms: Boon or Brake for Adaptation?

California Environmental Quality Act updates may open up more housing, but some are sounding alarms about bypassed environmental regulations.

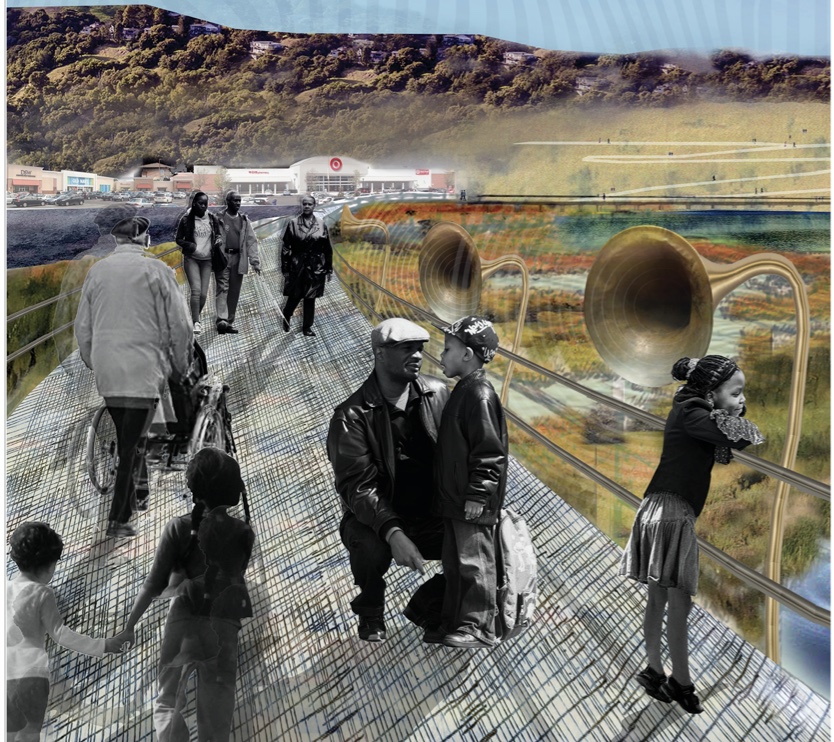

Repurposing Urban Lots & Waterfronts: Ashland Grove Park, Palo Alto Levee, and India Basin

In this edition of our professional column, we look at how groups are reimagining a lot in Ashland Grove and shorelines in San Francisco and Palo Alto.

Backyard Harvests Reduce Waste

A Cupertino Rotary Club program led by Vidula Aiyer harvests backyard fruit and reduces greenhouse gases.

Digging in the Dirt Got Me Into Student Climate Action

A public garden at El Cerrito High School in the East Bay inspired my love of nature and my decision to study environmental science at UCLA.

King Kong Levee: Two Miles Done, Two To Go

Two miles of levee are now in place as part of the project to protect Alviso and parts of San Jose, but construction will last much longer.

Making Shade a Priority in LA: An Interview with Sam Bloch

After witnessing fire disasters in neighboring counties, Marin formed a unique fire prevention authority and taxpayers funded it. Thirty projects and three years later, the county is clearer of undergrowth.

Without Transit Rescue Measure, Bay Area Faces Major Climate Setback

BART, Caltrain, Muni, and AC Transit could face devastating cuts, pushing thousands more cars onto Bay Area roads, unless voters intervene.