Beneath Oakland’s struggles with gentrification, inequality, and pollution, a single factor could play a role in addressing all these issues: trees. Trees do far more than add shade and property value to a city block; they can remove harmful pollutants from the air, reduce flooding, and perhaps most crucially in a changing climate, they can reduce heat. A 2019 investigation by NPR found that Oakland’s poorer neighborhoods are almost universally hotter than its richer regions (in fact, the city had one of the strongest correlations between heat and income in the country).

Volunteers have planted more than 3,500 trees in the last ten years. Still, Oakland continues to lose trees to disease, neglect, and drought, while trees and parks are still overwhelmingly concentrated in wealthy areas. This trend is tied to class and the unique geography of the city itself, which Derek Schubert describes as a “weird disparity.”

Schubert, a landscape architect, civil engineer, and volunteer urban forester, has worked on hundreds of tree-planting projects in Oakland over the past decade, all run by nonprofits and mostly on public land with the city’s blessing. The disparity he describes is the jarring difference between two general regions of the city: the flatlands and the hills. These two areas, which look as different as they are demographically, are practically a case study of national urban environmental trends. “If you look at these two patterns of settlement it’s a tale of two cities,” Schubert says.

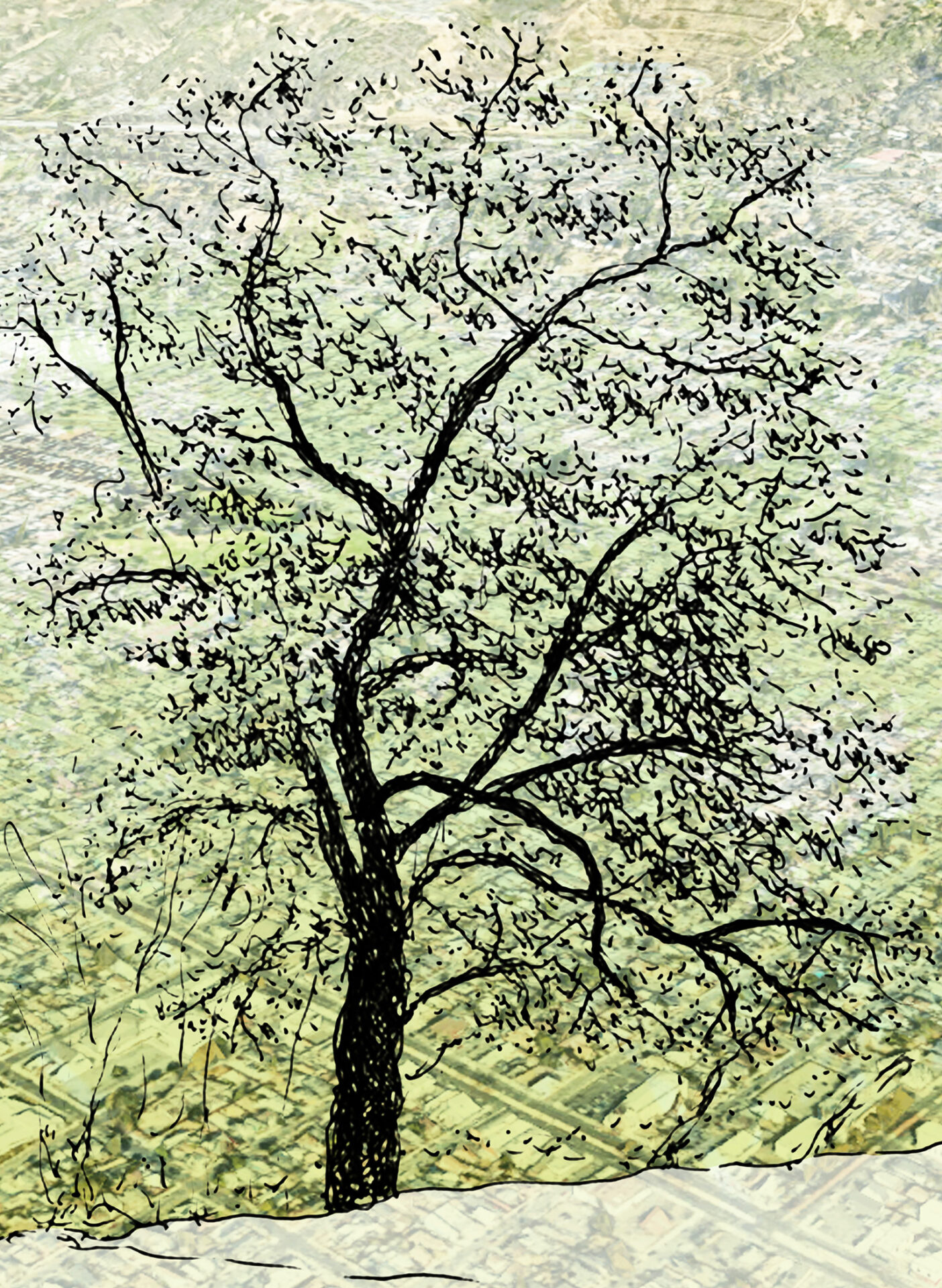

Looking down at the city from above, Schubert explains, “you could see what parts of town look green and what parts look gray; the flatlands are that grey part.” Running roughly from San Francisco Bay to the base of the coastal mountains that rise sharply on the eastern side of town, the flatlands are much less wealthy, more racially diverse, and less white than the forested hills.

The difference between flats (top) and the hills (bottom) on two Oakland streets..

Photos: Zack Boyd.

“Forested neighborhoods in American cities can be as much as 20°F cooler than tree-short neighborhoods.”

For John R. Oberholzer Dent, 23, this disparity runs deep. Growing up working-class in Oakland’s then-middle-class neighborhood of Temescal, Oberholzer Dent recalls how the hills seemed a world away from the block where he was raised. “You know it’s different up there,” he says. “Part of what was so different about the hills, actually uninviting, was that there were so many trees and landscaped sidewalks”

The stark difference between these neighborhoods is not purely aesthetic; trees play an important role in regulating the temperature of urban areas. In 2019, the New York Times reported on a national study from Portland State University that found that certain neighborhoods could be as much as 20°F warmer than better-forested areas within the same city. The researchers also acknowledged a link between income and heat in most major American cities. Obviously, wealthier residents may be more able to afford homes in green, shady neighborhoods, or at least to buy, plant, and maintain their own trees.

These differences have solidified through decades of discriminatory zoning policies in Oakland. In recent years, the city has seen dramatic gentrification (along with San Francisco, Oakland topped the list of the most gentrified American cities in a 2020 study reported in ABC News). Oberholzer Dent has noticed this trend in his own neighborhood of Temescal, as job opportunities now favor incoming residents drawn by the Bay Area’s tech-based economy. Often, he says, “neighborhood improvements” are accompanied by new green spaces to make them more enticing for newer, wealthier, and often whiter residents. Any plan to plant trees or create green spaces, he says, “[should] consider displacement and gentrification first, because it’s all going together.”

The future of tree-planting in Oakland is undecided. A 2020 city report made no mention of the correlations between income, demographics, green space, and heat, although it did encourage the city to set forestry goals for the future. Despite qualifying with the Arbor Day Foundation as a “Tree City, USA” for more than 30 years, Oakland’s Tree Services program has not been expanded to its previous size since it was cut by more than half during the Great Recession. While groups like Schubert’s Trees for Oakland (a project of the nonprofit Oakland Parks and Recreation Foundation) collaborate with the City of Oakland, most of their work happens on a neighborhood-by-neighborhood basis, often at the request of residents.

The 2020 report also fails to mention that the city as a whole is losing trees. Even though Trees for Oakland, the Sierra Club, Urban Releaf, and other groups, citizens and developers planted thousands of trees between 2010 and 2020, even more trees are dying. Harsh drought cycles over the last two decades have worsened the city’s losses.

While green spaces are essential for the health of all citizens, Oberholzer Dent also considers them essential for a more general quality of life.

“We deserve to look at our space and for it to look good, and for there to be leaves for our toddlers to crunch around in, and to have beautiful things happening on the street,” he says. “Most people don’t know about the temperature stuff, and they live with terrible air quality already. But, the more educated or the more involved that people get in this stuff, the more they’ll be able to care about it.”

MORE

- As Rising Heat Bakes U.S. Cities, The Poor Often Feel It Most”; NPR, 2019

- Summer in the City is Hot, but Some Neighborhoods Suffer More”; New York Times, 2019

- San Francisco-Oakland Tops List of Most Gentrified Cities in the United States, Study Shows”; ABC News 7, 2020

- Accessibility and Investment in North Oakland: MacArthur Area Case Study”; Center for Community Innovation, 2015

- Public Health Benefits of Urban Trees; The Nature Conservancy, 2019