The Lost Birds, A Review

In the San Francisco Bay Area, springtime brings thousands of migratory birds and their songs. Sounds like sweet whistle-like tweets from snowy plovers near the coast, the operatic song of black-headed grosbeaks and the rapid chaotic notes of warbling vireos in forests and parks, and the shrill call of Swainson’s hawks flying above. But this magnificent chorus occurs in the background of rapidly declining biodiversity. In the Americas, around 2.5 billion migratory birds have been lost since 1970, according to a 2019 study in Science. According to Audubon, more than half of the bird species in California are threatened by climate change.

The cry of a Swainson’s hawk adds nature’s music to this image. Video: American Bird Observatory.

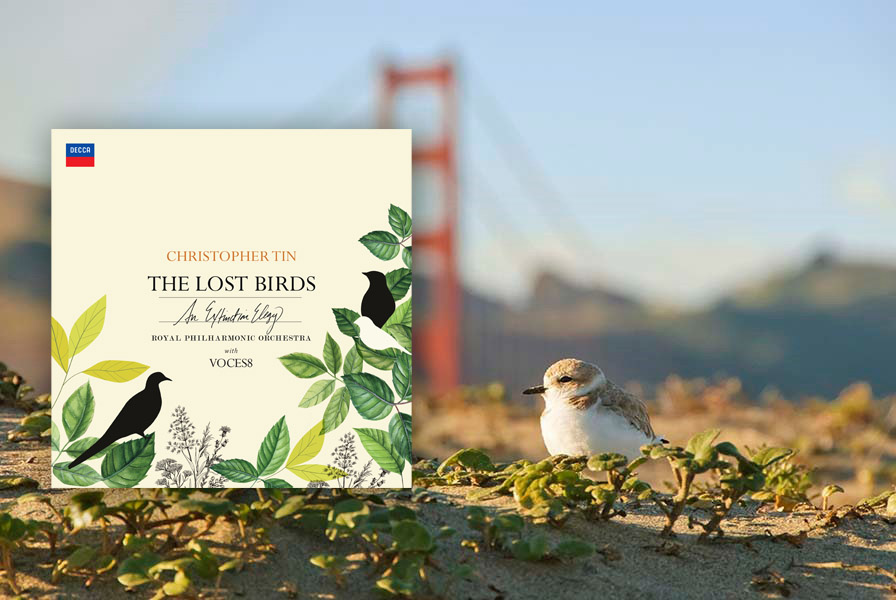

The beauty of these animals, their fragility, and this loss of avian diversity inspired The Lost Birds, the latest work by composer Christopher Tin, who is best known for scoring video games and movies. His choral piece Baba Yetu was the first song written for a video game to win a Grammy Award. Tin’s work is often buoyant, grandiose, and even cartoonish. The Lost Birds, composed during lockdown, takes a different approach. Released in September 2022, The Lost Birds is a tribute to extinct animals, a conversation with poets from the 19th century, and reflection about the future of the ecosystems we enjoy today.

The music, recorded in London with The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and British acapella octet VOCES8, follows the pastoral and romantic traditions of celebration of nature. If it was a painting, its palette would be based in turquoise and blues. In “Bird Raptures,” the violins accelerate to mimic birds taking off. In “The Will Come Soft Rains” the harp evokes the sound of drizzles in early spring.

Every eulogy needs words; Tin used the poetry of Emily Dickinson, Christina Rossetti, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Sara Teasdale — all women who wrote about nature and its tension with modernity, the industrial revolution, and rapid urbanization. In The Lost Birds, Emily Dickinson’s verse “the saddest noise, the sweetest noise” becomes a prayer for beautiful bird songs silenced by habitat loss and climate change.

A choral concert in the open spaces of the Grand Tetons performing music lamenting birds lost to extinction by Christopher Tin. Video: VOCES8.

In an interview with Presto Music, Tin mentioned that part of the inspiration for this work is “a concern for the wellbeing of the natural world and the world that I’m going to be leaving behind for my four-year-old daughter.” The music’s intimacy works as a sorrowful invitation to witness feathered beauty and tragedy. I sometimes have a similar feeling of appreciation and concern while birdwatching, seeing mesmerizing animals that might disappear in my lifetime. Although The Lost Birds is not an explicit call to action, I wondered if the allure of the music can serve as inspiration to engage with the environmental crisis.

The album starts with the instrumental track “Flock a Mile Wide”, which introduces the mood of wonder and woe. The song is inspired by the passenger pigeon, a species of bird that was endemic to North America and hunted to extinction. A subtle harp introduces the orchestra that slowly gains momentum as the song progresses, until it creates the sensation of millions of birds flying, covering the sky, and enveloping the listener.

Postage stamp of band-tailed pigeon. Art: Clement Guzman.

Passenger pigeons used to be so common that migrating flocks would number in the millions. The controversial father of ornithology in the United States, James Audubon, wrote in 1813 that “the light of noon-day was obscured as by an eclipse” by a flock of passenger pigeons. Today their closest living relative, the Band-tailed pigeon, breeds in Northern California in spring and summer and migrates in the fall to the south of the state and to Mexico, in flocks of up to 300 individuals. Their numbers are decreasing; earlier this year, an avian parasite killed hundreds around the Bay Area and the Sierra Nevada.

When the passenger pigeons disappeared, people refused to believe it. In 1913 William Hornaday, the director of the New York Zoological Park, wrote “millions were destroyed so quickly, and so thoroughly en masse, that the American people utterly failed to comprehend it.” At the time, people could not believe a species that numbered in the millions could just be gone. Hornaday reports that some believed the bird had taken permanent refuge in Mexico or South America.

Since then, other species have joined the pigeons; many scientists believe that the planet is in the midst of its sixth mass extinction event. Art is not a useful tool to understand the science of climate change or biodiversity loss, and music is not the best way to explain why species disappear. But bearing witness to tragedy can inspire action to save what has not been lost yet.

William Hornaday, for example, lived through the disappearance of the passenger pigeon. His later work as an author, conservation activist, and president of the New York Zoological Park helped to save the bison from extinction. Today there are bison ranches in northern California and one herd on the island of Catalina; these bison play a role in protecting biodiversity and preventing wildfires.

The environmental crisis we face today is overwhelming. Grieving and accepting what we have lost might be a good first step to inspire us to take action to protect what remains. In the last track of the Lost Birds, Tin reprises the instrumental theme that opens the album but with the verses written by Dickson “Hope is The Thing With Feathers.” Tin closes The Lost Birds with the voices of VOCES8 singing several times, with intimacy and urgency, the word hope.