The Itchy Cost of Hotter Summers

We tend to think of mosquitoes as pesky bugs: they buzz behind our ears during cookouts and leave itchy bites on our arms. But bug bites can bring more than irritation. As climate change exacerbates heat waves and alters precipitation patterns, climate scientists expect cases of mosquito-borne disease to increase.

Mosquitoes thrive in warm, wet environments. Temperature is one of the most important factors for their survival, and a warmer climate means mosquitoes go through their lifecycle more quickly, speeding through the larval stage to become adults with the ability to transmit disease. Higher temperatures may also make mosquitoes infectious more quickly after biting a host.

“We’re going to see disease shifting to places it’s never been before,” says Desire Nalukwago, a Ph.D. student at Stanford University who is mapping mosquito abundance in California.

Just last year, two cases of dengue fever, a disease transmitted to humans through mosquito bites, were reported in Southern California. Dengue fever is typically contracted when someone visits a tropical region like Southeast Asia, is bitten by an infected mosquito, and returns home with the disease. But neither of these people had traveled outside of the United States.

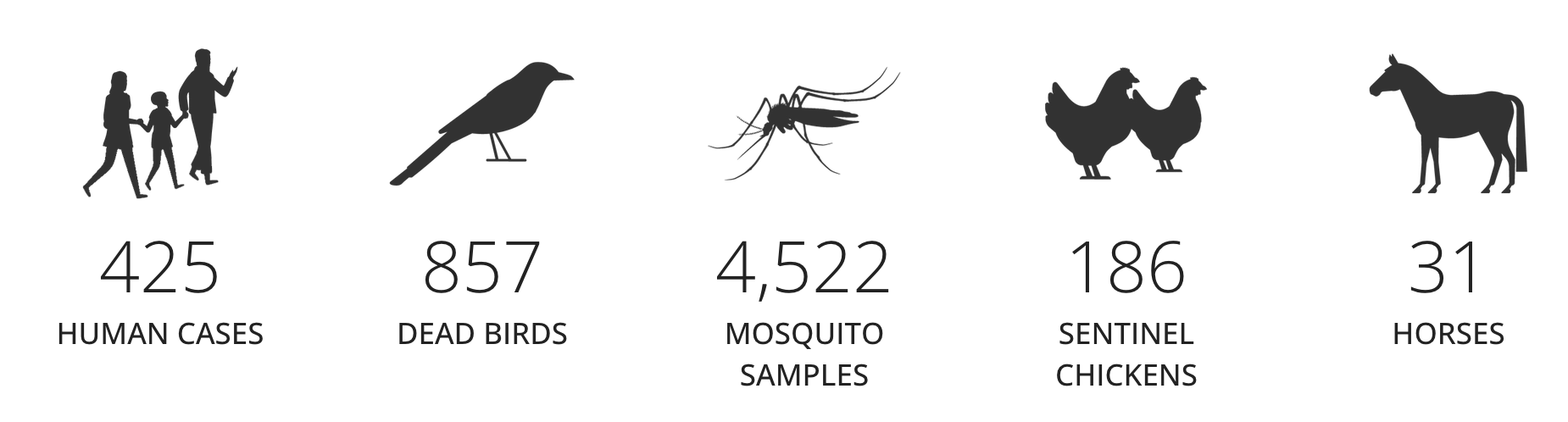

West Nile Virus, another common mosquito-borne disease, is also slowly on the rise in California. West Nile originates in birds, and mosquitoes become vectors for the disease when they feed on the blood of an infected bird or human. Though 80% of humans infected are asymptomatic, the virus can cause symptoms like fever, headache, nausea, and, in rarer cases, fatal neurologic illness. Across the state, there have been over 300 reported deaths from the virus since its introduction in 2003.

The risk of West Nile has been especially alarming in the semi-arid Central Valley, as areas like Sacramento exhibit hotspots of transmission each year. Since these insects lay their eggs in pools of standing water, flooding during the winter before last created new breeding grounds and caused populations in the Central Valley to skyrocket.

West Nile activity in California 2023 to date (March 2024): Cal Dept. of Health

The rocket could reach a limit, however. Mosquitoes are quite sensitive to temperature and can only survive within a narrow range. As global temperatures rise due to human-induced climate change, making warmer regions hotter and drier, scientists say mosquitoes may buzz northward to find more suitable habitat.

The tropical mosquito species Aedes aegypti, which is known to spread dengue fever, appeared in California in 2011. Scientists fear this species, among others, is creeping northward. Previously low-risk areas, like the San Francisco Bay with its cooler climate, may be the next site of concern.

A warmer and drier California means seasons of drought, which could also increase the risk of West Nile infection. Although mosquitoes need water to reproduce, a scarcity of water can actually be a bigger concern, according to Andrew MacDonald, disease ecologist and professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

“In periods of drought you can actually have a higher risk of West Nile Virus because there’s more interaction between birds and mosquitoes,” says MacDonald. When there is drought in an area, animals, including humans, will seek out the few available water sources, making the exchange of disease more likely.

MacDonald’s research in the Central Valley involves using satellite technology to identify and monitor potential breeding areas for mosquitoes. His team studied flooding in 2023 and noted that despite an uptick in the number of mosquitoes in areas like Kern County, the same uptick was not seen in West Nile cases.

While the areas of California at highest risk of West Nile can’t be pinpointed with certainty, scientists do know that the mosquito species that transmit West Nile are found in both urban and rural areas. People who are outdoors for most of the day in either setting, from unhoused people in cities to agricultural workers in the Central Valley, may be particularly vulnerable. Tracking this risk is difficult, however, and many cases go unreported.

Empty your garden pots and play structures of standing water, where mosquitoes can quickly breed. Photo: Ariel Okamoto

There isn’t yet a treatment or vaccine for the mosquito-borne diseases transmitted in California, so preventative measures year-round remain essential to reducing risk. Scientists suggest wearing protective clothing outdoors like long sleeves, thick pants, and hats with mosquito nets. The mosquito species that transmit West Nile are most active between dusk and dawn, summer through fall, so experts recommend applying insect repellent with ingredients like DEET during risky times of day. Standing water, where mosquitoes breed, can also be managed. Mosquitoes can breed in pools of water as tiny as flower pots and rain gutters, so containers near your home should be emptied every four days. California’s Vector Control Districts offer free inspection and treatment for standing water like ponds and will test dead birds for West Nile.

Scientific communities are still working to understand who is at greatest risk for West Nile in the near future, but as Nalukwago notes, “at the end of the day, this is going to impact all of us.”