The Case for Climate Castles

“Whether it’s Hogwarts or Winterfell or the Louvre Pyramid or Coit Tower, the idea of castles is inspiring. ”

As climate change throws more extreme events at us, and as we continue clinging to the comforts of oil and gas despite a warming world, isn’t it time to think bigger, bolder, further ahead?

Cities and utility systems are not being redesigned to be more efficient and flexible fast enough. In some cases, it’s quite possible it would be less expensive and more climate-resilient to build entirely new systems in and around the urban footprint rather than trying to update the old.

People’s need for healthy housing they can afford isn’t keeping up with snowballing social and environmental challenges either. Slogging away at more infill, more granny cottages in the backyard, more “affordable” housing units, more development in areas within the urban footprint and near transit (“PDAs”) is critical but incremental at a time when thousands of people are starting to wonder where they can move to be safe.

Where could you build climate-resilient castles or self-sustaining developments in the Bay Area? Map: Amber Manfree.

Within California, every year, thousands of residents are being forced to move away, temporarily or permanently, from wildland borders and forest fire zones, from smoky and overheated valleys, from crumbling coasts and swelling floodplains and sliding hillsides and water-starved farmland. Not everyone can move to Vermont. Meanwhile, climate refugees from all over the world continue to come to California looking for a place to be safe (see Startling Facts about migration below).

Climate effects are outpacing our ability to adapt. What if we began designing new mini-cities with all this in mind now? Could we design them to function without cars, to be energy self-sufficient or off the grid, to recycle water and filter air? Could a superstructure – a “town castle” with services at the heart of these new resilient settlements — support a hinterland of greenhouses, barter and trade markets, aquaculture ponds and temporary housing for the displaced? Sound like fantasy?

I, for one, would love to live in a climate castle! Whether it’s Hogwarts or Winterfell or the Louvre Pyramid or Coit Tower, the idea of castles is inspiring.

As part of KneeDeep’s new Radical Rethink series, focused this month on housing, we asked young people studying architecture at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo what a climate castle might look like? We suggested they omit cars, include energy and water efficiencies, make room for local food and temporary housing, and provide public spaces. Turns out many were already thinking along these lines in their class projects.

What follows is just a teaser for a climate castle design competition KneeDeep hopes to launch soon (sponsors welcome!).

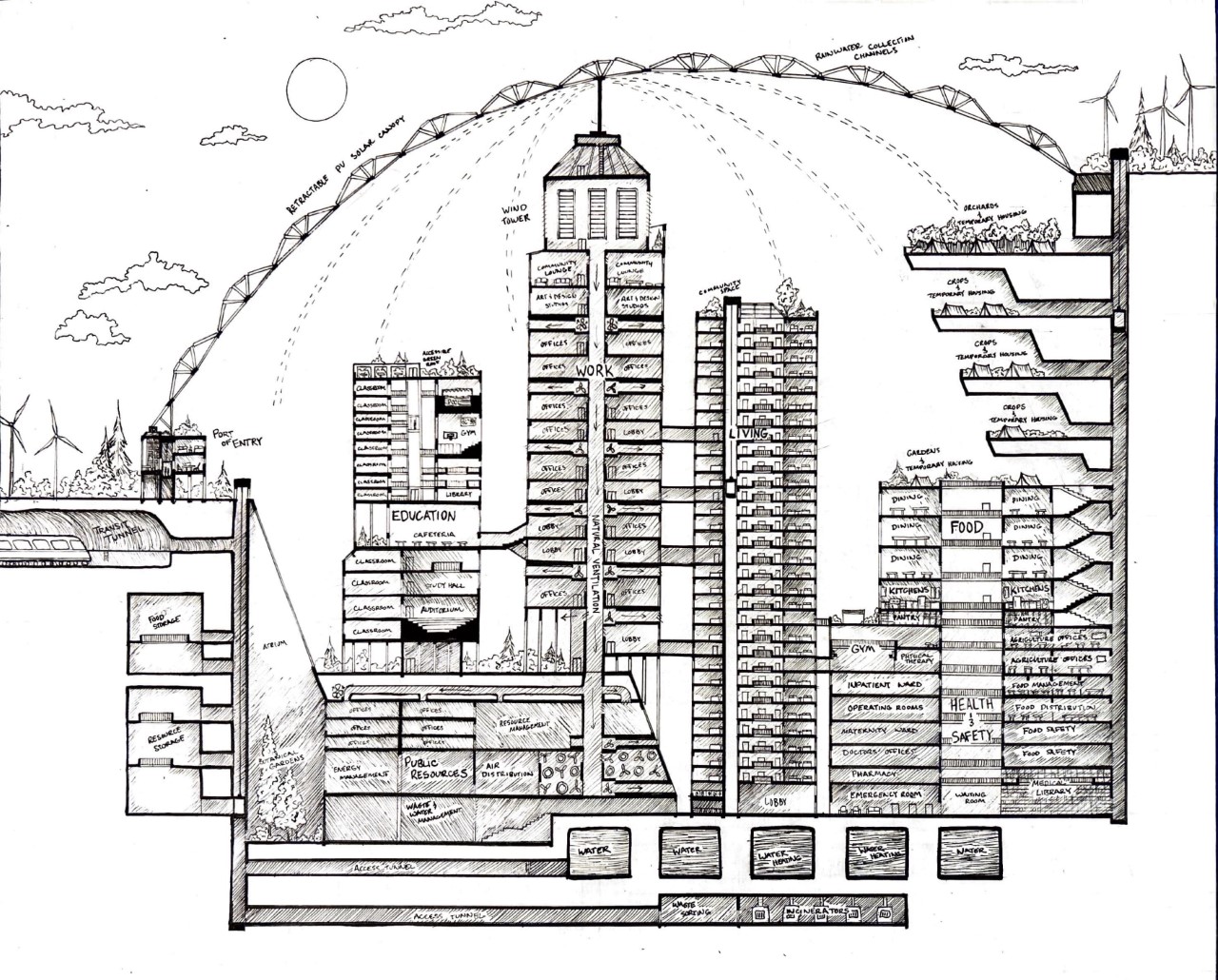

ABOVE: Fifth-year architecture student Ben Hoffman admits he has “a sweet spot for envisioning idealistic futures, particularly when they involve a concept so real and close to home.” Hoffman originally hails from a rural community dealing with the repercussions of climate change and overly dense, tinderbox-like forests. His architecture thesis also deals with these repercussions, and he attributes struggles in bouncing back or properly preparing for disasters to a lack of resources and civic space, as well as a loss of local industry. “These are all factors I have attempted to address in my castle drawing through the use of common and accessible industrial components like scaffolding and shipping containers, along with the promotion of individual produce cultivation, central market and gathering space, united living quarters, and small-timber wood utilization. Historic castle systems and a recent viewing of the 1978 documentary Mysterious Castles of Clay offered inspiration for the castle’s form and functional passive heating/cooling strategies,” says Hoffman.

Art: Lily Hanna.

ABOVE: To architecture student Lily Hanna the ideal eco-friendly city is one that coexists with the ecologic systems already in place. “I grew up in a small mountain town in Colorado, which inspired this playful idea that people ‘live in the hills.’ While this drawing is an exaggerated example, I do think buildings need to be more connected to nature, for the well-being people and the environment,” she says.

ABOVE: Floating platforms rearrange this aquatic community into a cluster for protection during storms and spread out when it is calm, says Sophia Walker of her fifth-year architectural thesis project entitled Me and my friend: the environment. “Moving forward, humans must understand that they are a part of nature instead of trying to control it. My project is an aquatic community that is responsive to, and reliant on, seasonal change and natural weather events. Life on the water is different than on the land. The community is not ruled by sedentary settlement and abstract productivity. Instead, residents have an intimate relationship with the environment and the buildings they inhabit. Daily activities, food harvest, spatial conditions, and social interactions are determined by the weather and tides. This new give and take between humans and their surroundings leads to a sense of vulnerability and adaptability. The community also grows and harvests its own food through regenerative ocean farming and collects its own energy from solar, wind, and waves. In the background you can see the weather tower and rain/solar collector which anchor the community in the water,” says Walker.

Design: Abbey Lau.

ABOVE: Abbey Lau describes her climate castle as essentially a self-sustaining micro city. “All the food, water, and energy are produced and managed on site, and it’s fully walkable and accessible. It also offers lots of sunlight and green space to improve the living quality of its inhabitants and has plenty of extra resources and temporary housing to respond to refugees from climate catastrophes,” she says. Now in her fourth year in Cal Poly architecture program, Lau is passionate about creating a better world through design.

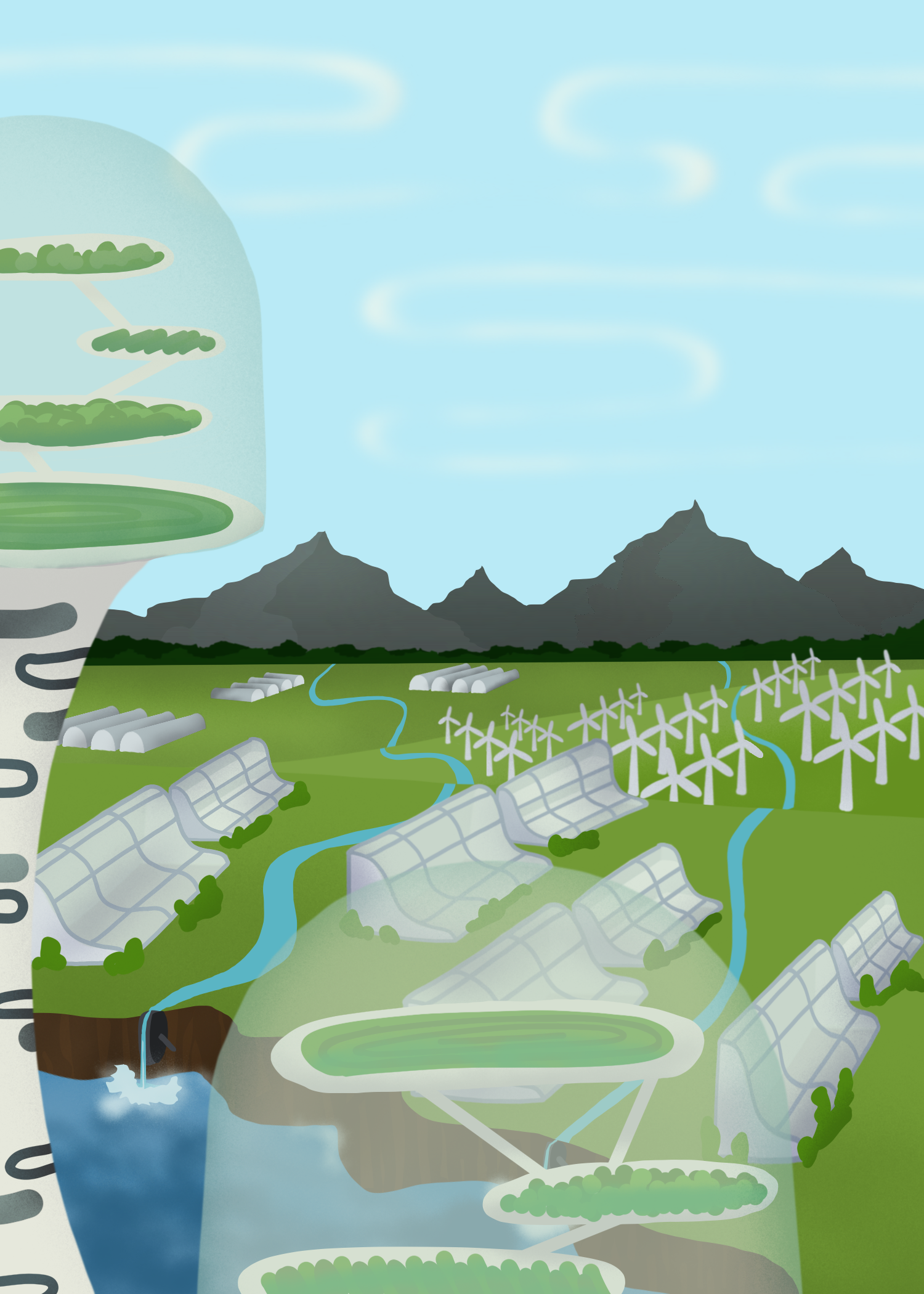

AT RIGHT: “I have been interested in building things since I was a kid, and I’ve known for a long time that I wanted to become an architect,” says Sophia Burkhart, who is studying both architecture and sustainable environments. “My climate castle depicts development that works harmoniously with nature, using rivers for energy and transportation, as well as harnessing power from the wind and sun. Community gardens flourish atop centralized mixed-use buildings that work to feed the population and reduce transportation emissions. This is an idealized vision of course, but I am optimistic that the cities of the future can still be the magical places of connection that they are today but in an entirely sustainable way,” she says.

ABOVE: Siena Lopez, a first-year architecture student at Cal Poly, says her climate castle aims to emphasize how structures can adapt to the changing climate while also keeping aesthetics and serving the community: “I was very inspired by environmental sustainability and solar punk for this art piece. I wanted to incorporate lots of solar panels into the buildings while also having fun with the design choices. The bridge to the climate castle is lined with 3D fireproof circular temporary homes for climate refugees. The buildings embedded into the hills include vertical farms and orchards that double as a communal space. The airborne wind turbines can be reeled in and out in case of any extreme weather events. Windows are clear solar panels that also let natural light in for health purposes,” she says.

Layout: Mikki Okamoto.

A Few Startling Facts about Climate Migration

Research by Isabella Eclipse

Today more than ever, people around the world are on the move. California once attracted thousands of migrants because of its great weather and beautiful landscape, but drought, fires and inequities have changed that. While Californians are moving within the state to avoid climate threats, they are also moving out of state in record numbers. At the same time, hundreds of thousands wait at the U.S.-Mexico border in unsustainable conditions, fleeing disasters in their own countries. Just how dire the uptick in migration has become, and how climate change is exacerbating north-south population shifts, is apparent in the data below. Exact numbers are hard to estimate because the reason for migration is often a combination of factors.

Solar castle at night. Art: Siena Lopez.

Global Basics

- “Climate-fueled disasters were the number one driver of displacement over the last decade – forcing an estimated 20 million people a year from their homes.” (Oxfam)

- On average, over the past decade, three times as many people were forcibly displaced by extreme weather than by conflict. (Oxfam)

- Although climate-related disasters are occurring in many different countries, the worst impacts will be concentrated in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America. These locations are both more geographically prone to extreme weather events and less prepared to cope because of poverty, political instability, and other pre-existing issues. (Groundswell)

- In 2020, the global total number of persons displaced by disasters was around 7 million across 104 countries and territories. (World Migration Report)

- Most new internal displacements in Latin America and the Caribbean in 2020 were due to disasters, not violence and conflict. Honduras recorded the largest number of internal displacements triggered by disasters (937,000), followed by Cuba (639,000), Brazil (358,000) and Guatemala (339,000). (World Migration Report)

- In 2020 there were about 46,000 new displacements due to extreme temperatures, and 32,000 new displacements due to droughts. (World Migration Report)

- By 2050, the World Bank estimates that 140 million people will be displaced within their own countries by disasters. (World Bank).

Internal displacement within the U.S.

Internal displacement within the U.S.

- In 2018, 16.1 million people globally were displaced because of weather-related disasters. More than 1.2 million were Americans. (Urban Institute)

- Hurricane Michael displaced an estimated 464,000 people in the Southeast before and after August 2018. The November 2018 Woolsey fires displaced 182,000 in California.

- From 2011-2021, ninety percent of counties in the U.S. had federal disaster declarations, an area covering over 300 million people. In 2021, there were 20 separate billion-dollar climate disasters which led to more than 688 direct or indirect fatalities. (Rebuild By Design)

- Temporary displacement often leads to long-term resettlement because recovery is a long process and displaced people find opportunities elsewhere. (Urban Institute)

- Preliminary analysis suggests that people displaced in the U.S. tend to move to nearby urban areas. (Urban Institute)

- The arrival of climate migrants can cause conflict in the communities they move into because they are perceived as competition for jobs and housing. They can also put a strain on already failing infrastructure. (Urban Institute)

- In addition to adaptation to flooding, drought, and heat, managing regional migration is key to climate resilience. (Urban Institute)

- According to a recent YouGov poll, 55% of Americans have experienced extreme weather events. 1 in 6 of those people are now considering moving elsewhere. Almost half of those surveyed by the real estate broker Redfin last year said natural disasters had played a role in their decision to move in 2022. (Deseret News)

- According to a Cornell study in the Climatic Change journal, at least 57% of Americans believe that climate-related events will influence where they decide to move in the next decade. (Byungdoo, Kay, and Schuldt 2021)

Internal displacement in California

- The Atlas of Disaster shows that California had 25 federal disaster declarations from 2011 to 2021 – the highest in the country. (Rebuild By Design)

- Destructive wildfires are causing many Californians to move away from their homes or leave the state altogether, often moving to “temperate northern states” and areas like New England and the Upper Midwest. (Yale Environmental 360)

- Although there is no solid data, these articles suggest that people are moving away from Oakland because of climate change (The Globe and Mail) and wildfires. (The Nation)

- To make matters worse, when California’s population was growing (1990 – 2010 saw a 25% increase to 37 million people) half of new housing was built in the wildland-urban interface, an area particularly vulnerable to fire. (Deseret News)

- Cautionary tale of Paradise, CA (The Guardian)

- After the Paradise Fire, most residents evacuated to the nearby town of Chico, but there already was a severe housing shortage and only those who could afford the high prices found new homes. Everyone else had to leave the area or became homeless and live out of their cars.

- Chico was unprepared for this disaster because it didn’t build enough housing to keep up with demand.

- Even in 2021, the county estimated that as many as 6,000 to 7,000 unhoused households in the Chico and Oroville area were living in trailers and tents, many of them displaced by the later Camp fire and 2020 wildfires.

- The tense situation has caused conflict and divided the community. Some Chico residents have become hostile to unhoused prople living in the area, harassing them and trying to have them removed by the city.

- In California, climate disasters are combining with a housing shortage caused by lack of construction and unaffordability. The state estimates at least 2.5 million homes are needed in the next eight years to catch up to demand. (PBS Newshour)

A Closer Look at Central America -- Home to Many Migrants to California

California is the main destination for Central American migrants arriving in the United States. About 25 percent of Central American migrants live in California, with a majority concentrated in Los Angeles but a significant population in the San Francisco/Oakland/Berkeley metro area (Migration Policy). Many recent migrants are fleeing “natural” disasters even more than poverty, famine and other factors.

- In 2020 hurricanes Eta and Iota caused major destruction in Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. About 100,000 families were displaced and 6 million people affected by floods and landslides. The flooding washed away many agricultural fields, causing food insecurity and economic losses. (WOLA)

- Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua were especially vulnerable to disaster because they had been struggling with poverty, violence, and corruption for years, and their economies had been weakened by the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The governmental response to Hurricanes Eta and Iota was weak and disorganized. In Honduras the government had yet to repair damaged infrastructure several months after the hurricane. In Guatemala, indigenous communities in hard-hit rural areas did not receive federal support for their search and rescue operations. (WOLA)

- Drought, especially in the “dry corridor” of El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala, is also a significant cause of migration from Central America to the United States (Migration Policy)

- The rise in disaster displacement in these regions is already leading to increased migration to the United States. For example, many of the migrants apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border in recent years are Central American migrants fleeing recent hurricanes Eta and Iota. (WOLA)

- The population of Central Americans in the United States has increased by 24 percent since 2010 with 3.8 million Central American immigrants in 2019. (Migration Policy)

- Over 541,000 of the more than two million migrants who arrived at the southern U.S. border in fiscal year 2022 came from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. (Council on Foreign Relations)

The World Bank estimates that Mexico and Central America alone will have anywhere from 1.4 to 2.1 million climate migrants by 2050. (WOLA)