Summer Tales of Fire & Heat

Every Bay Area summer bathes the region in both heat and fog, not to mention occasional wildfire smoke. As July expires and August looms, KneeDeep revisits some of our most thought-provoking stories about how we experience hot weather and fire season, and what local communities and governments are doing to protect us from impacts. We especially want to daylight the in-depth coverage we were able to undertake in our now complete Extremes-in-3D series.

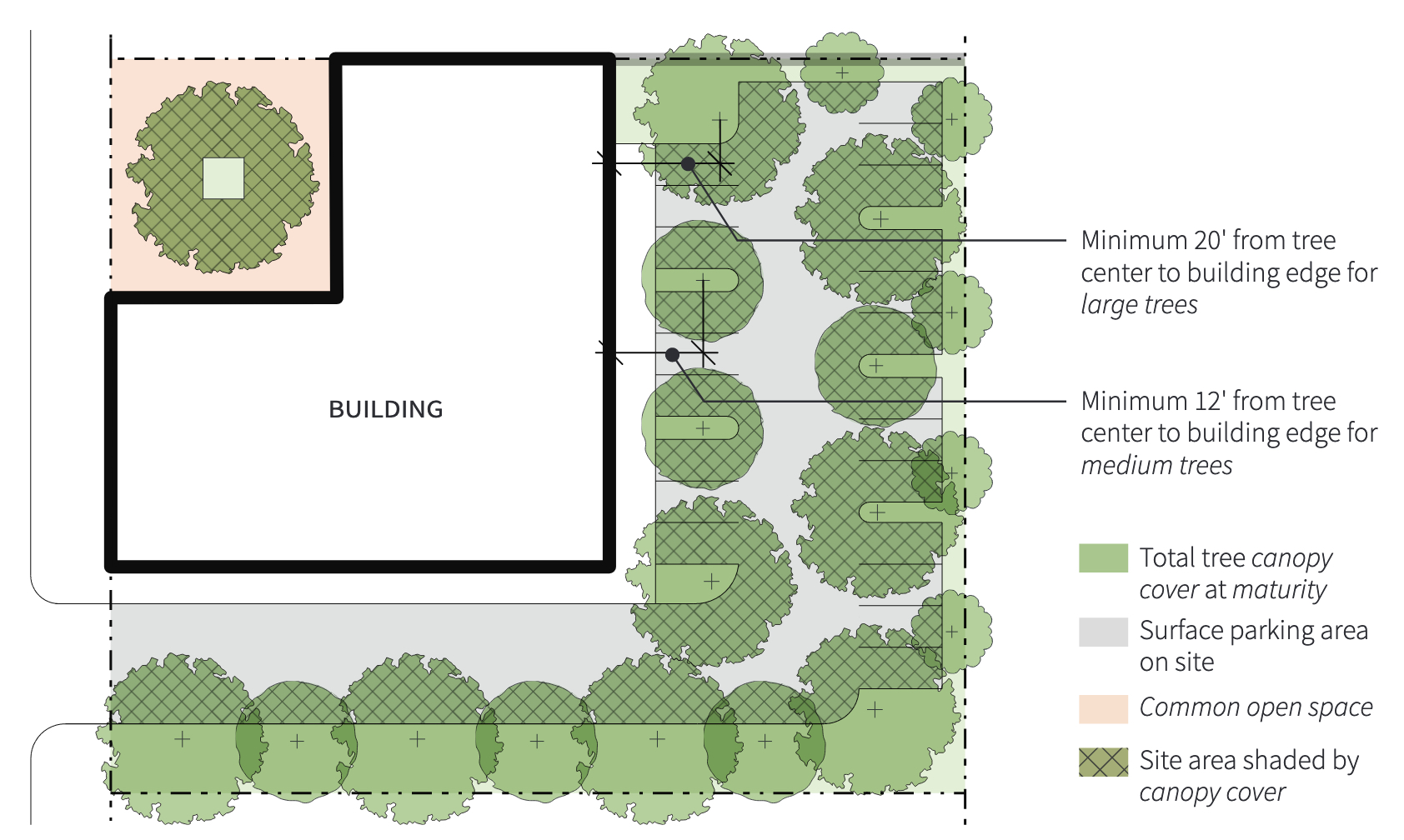

Asphalt roadways buckled in 2021 in Washington state under the searing sun. In 2022, tiles melted off a museum rooftop in Chongqing, China, and near Concord, a BART train derailed when the tracks warped in blowtorch conditions. The world is warming, but cities, especially, are feeling the heat. This “urban heat island effect” concerns urban planners and health officials around California. Now, they’re studying measures like rooftop gardens and heat-reflecting roads, both of which can help reduce a city’s temperatures. Image: San Jose Design Guidelines

The Bay Area’s mild weather is a liability in the face of all kinds of growing heat risks, from temperature swings to hotter nights. The average summer temperature can vary widely, and locals will experience a very different baseline if they live in the notoriously foggy Sunset district of San Francisco or in Solano County’s farmland near Dixon. If your town’s summer gradually warms up until most days are around 85 degrees out, you’ll probably not be too uncomfortable. But if you live in a place that rarely gets over 70 degrees, a sudden week of hotter days can be crippling. But what exactly—geography, surfaces, weather, buildings—makes the heat linger? Photo: Stephen Lam/ San Francisco Chronicle/Polaris.

Mauricio Juarez recalls when the kitchen temperature in the San Diego County Jack-in-the-Box where he works reached 102 degrees Fahrenheit. Employees passed out from the heat and paramedics were called, but it took a workers’ strike to get managers to install an air-conditioner. Juarez was one of a long queue of indoor laborers who pleaded with the Standards Board of the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health to implement long-awaited rules, developed almost five years ago, to protect indoor workers from potentially lethal heat. While state leaders and legislators have voiced concern, meaningful action has been slow to come. Art: Alyson Wong

Summer heatwaves often find my daughter and I retreating from our non-air-conditioned home to find somewhere to swim — the local public pool, a river, the ocean. But when we can’t go swimming, I get creative. I have always overheated easily, so I have been building my arsenal of cooling methods since childhood: early techniques included dunking my head under a faucet so my hair gets wet, spritzing my skin with a spray bottle, and keeping a baggie full of wet bandannas so I’ll always be able to put around my neck. Photo: Jacoba Charles

During a typical day at work in the eastern Coachella Valley’s agricultural fields, Silvestre Caixba struggles to find relief from the desert heat. As he runs errands outside in his everyday life, there are also few areas where he can step into shade or cool down. Made up of mostly dusty land within the dry, open desert, unincorporated towns in the east valley lack not only trees but also public green spaces and buildings that could offer adequate shade, where residents could find refuge from the 120-degree days. A master plan for shade equity aims to change that. Photo: KDI

In August 2020, I received an ominous automated call telling me to leave the area immediately. We were among thousands of residents of the San Lorenzo Valley facing mandatory evacuation from the CZU Lightning Complex wildfire headed our way. When we fled the house in the Santa Cruz mountains that we had been living in for just nine months we knew exactly two of our neighbors. But it’s a bittersweet truth that nothing brings people together like a natural disaster, and our story is no different. Since then, I’ve become part of a community that has wised up to fire. Photo: Steve Kuehl

When Sonoma County residents smell smoke, they usually hop on social media or check some alert services like Nixle or PulsePoint to find out what’s going on. The need-to-know response follows five years of wildfires — and in some cases, numerous evacuation notices. Eventually, fire-affected communities started sharing info in organized groups on social media which isn’t really designed for quickly and accurately sharing disaster alerts. That’s why a group of technologists and community fire experts teamed up to create a new way of updating communities during disaster called Watch Duty. Photo: Peter Rubissow

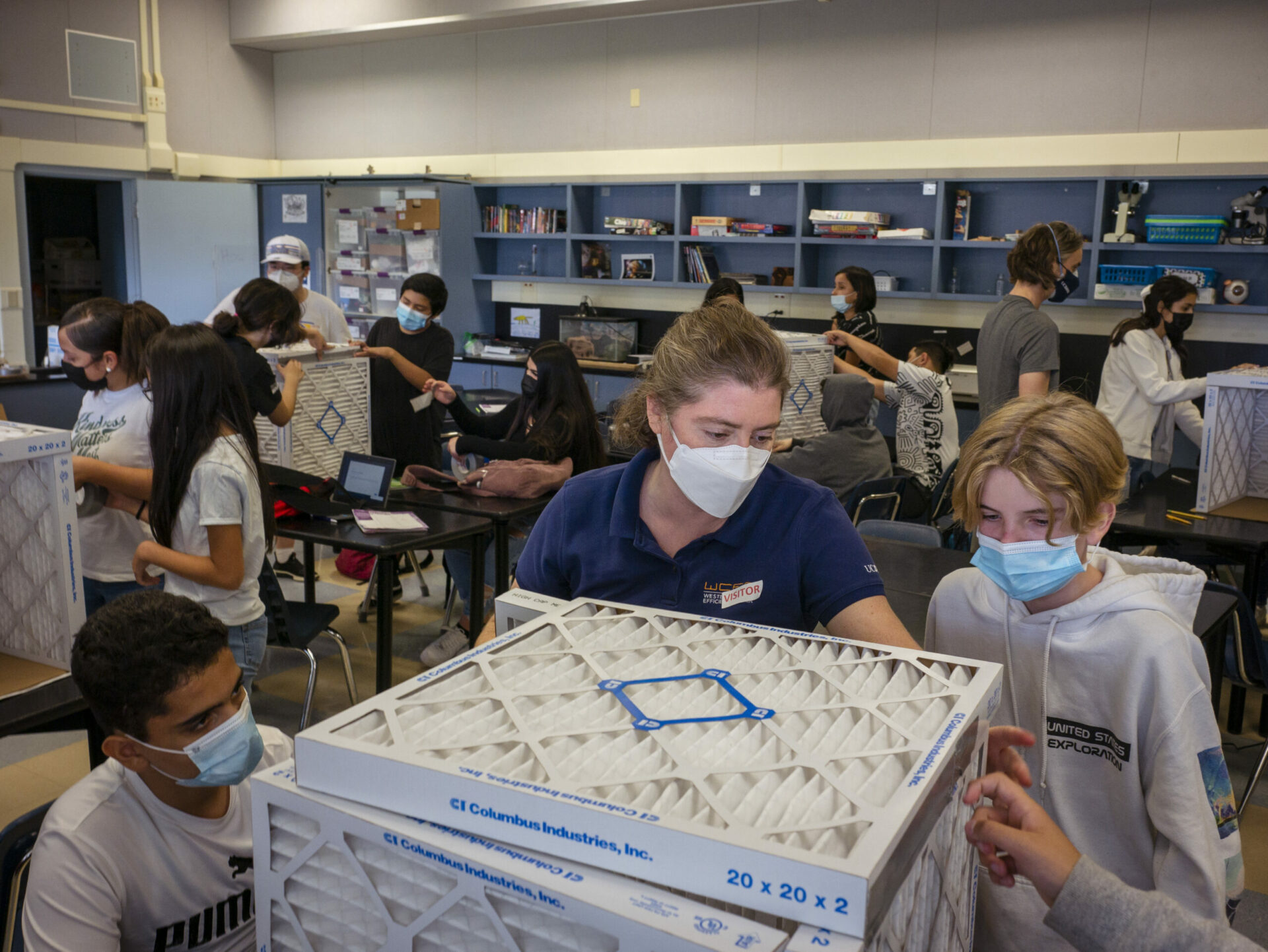

When wildfire smoke fills the air, is it safe for students to go to school? “My son has asthma, so when it’s smoky I really want to know what his day is going to look like,” says Nancy Metzger-Carter, a teacher in Santa Rosa. Almost half of the top 20 largest fires in California history have happened in the past three years, overlapping with a pandemic that stretched schools to their limits. In response, the Bay Area Air Quality Management District has just finished retrofitting 16 vulnerable elementary and middle schools with high-performance air filtration systems to get ahead of future fire seasons. Photo: Maurice Ramirez

Note to Readers:

If you have follow up information on any of these stories – what’s happened since they published? – we’d love your feedback. Email editor@kneedeeptimes.org