Storm Surge Resilience Jigsaw Confounds New York

“We all need to be shifting our dollars and attention pre-disaster, rather than post-disaster.”

In downtown Manhattan on a rainy night in December 2022, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was giving a presentation. Before the crowd of a few dozen, Colonel Matthew Luzzatto, Commander of the New York Corps, introduced the topic everyone had come to learn about: the New York-New Jersey Harbor and Tributaries Study.

“In the Army, the commander’s responsibility is to be at the location of the most important mission that that unit has ongoing,” Luzzatto said. “This public session is the most important thing going on in the district right now.”

The Harbor and Tributaries Study, or HATS for short, is the Corps’ plan to protect the New York metro area from storm surge and coastal flooding. It aims to protect the people and infrastructure that live along — and sometimes right up against — the area’s rivers, inlets, spits, and bays. In places like Manhattan and Queens, the waterfront is lined with tall residential buildings and commercial skyscrapers. The area in the study includes 25 counties in New York and New Jersey and seven cities, including the nation’s densest and populous in the nation — the five boroughs of New York.

Manhattan goes dark during Hurricane Sandy. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

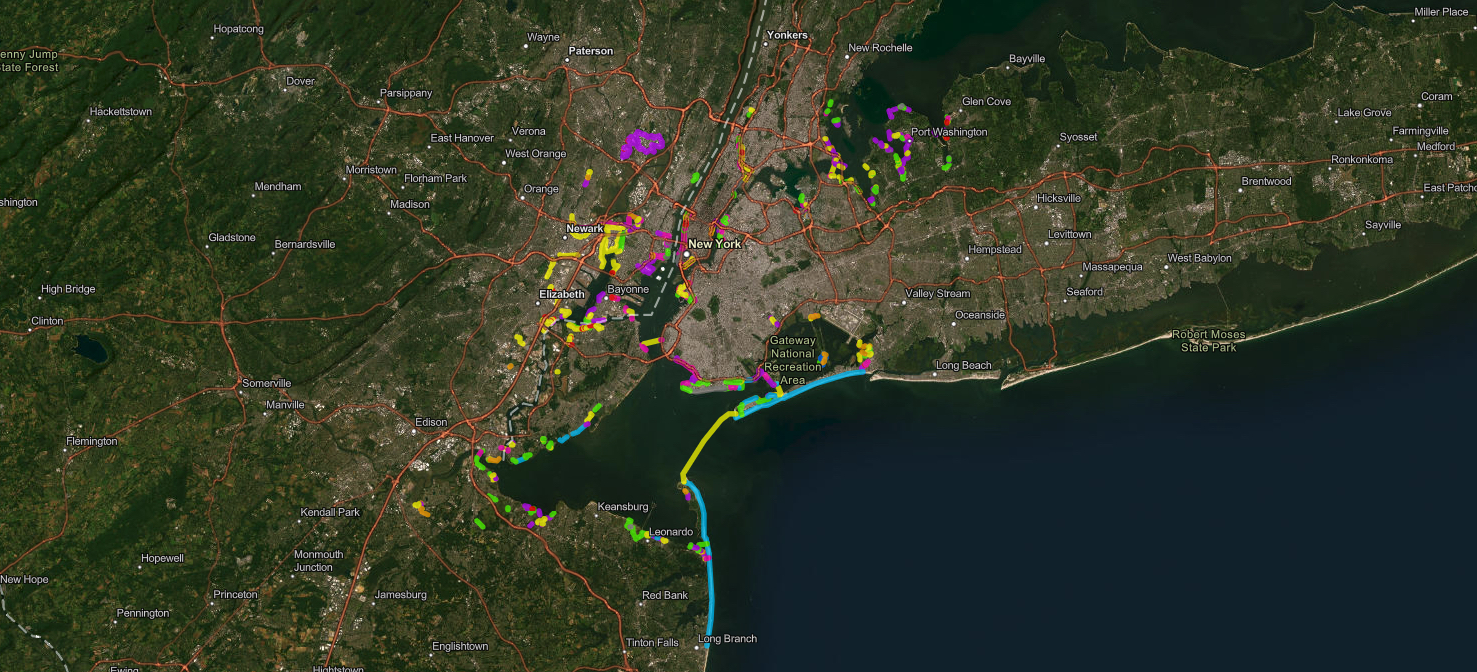

The HATS plan’s risk management alternatives in different colors. The recommended alternative, 3B, is in pink (see also below). For Bay Area residents, the longest yellow line evokes former San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo’s proposed sea-level rise barrier under the Golden Gate, a regional non-starter. Map: USACE.

The states of New York and New Jersey, New York City, and the federal government have all been paying attention to flooding risks and sea level rise since Hurricane Sandy hit the coast ten years ago.

The HATS study would be the biggest and widest-reaching coastal resilience project the region has seen thus far. It would re-engineer New York’s waterways, adding seawalls, levees, and other flooding protection. “This is not the first coastal storm risk management study in this area,” says Bryce Wisemiller, project manager on the HATS study. “Ideally, it would be the last.”

But some advocates say it is still just one piece in the jigsaw puzzle that is resilience planning in the New York area, which has struggled to come up with a comprehensive vision of the future.

And while Corps officials say they are working hard to coordinate between several jurisdictions and governments, Wisemiller admits there are challenges. “Between New York State, New York City and New Jersey, the governmental structures are so different.” Wisemiller said. “We’ve tried to work from existing mechanisms that are there for us.”

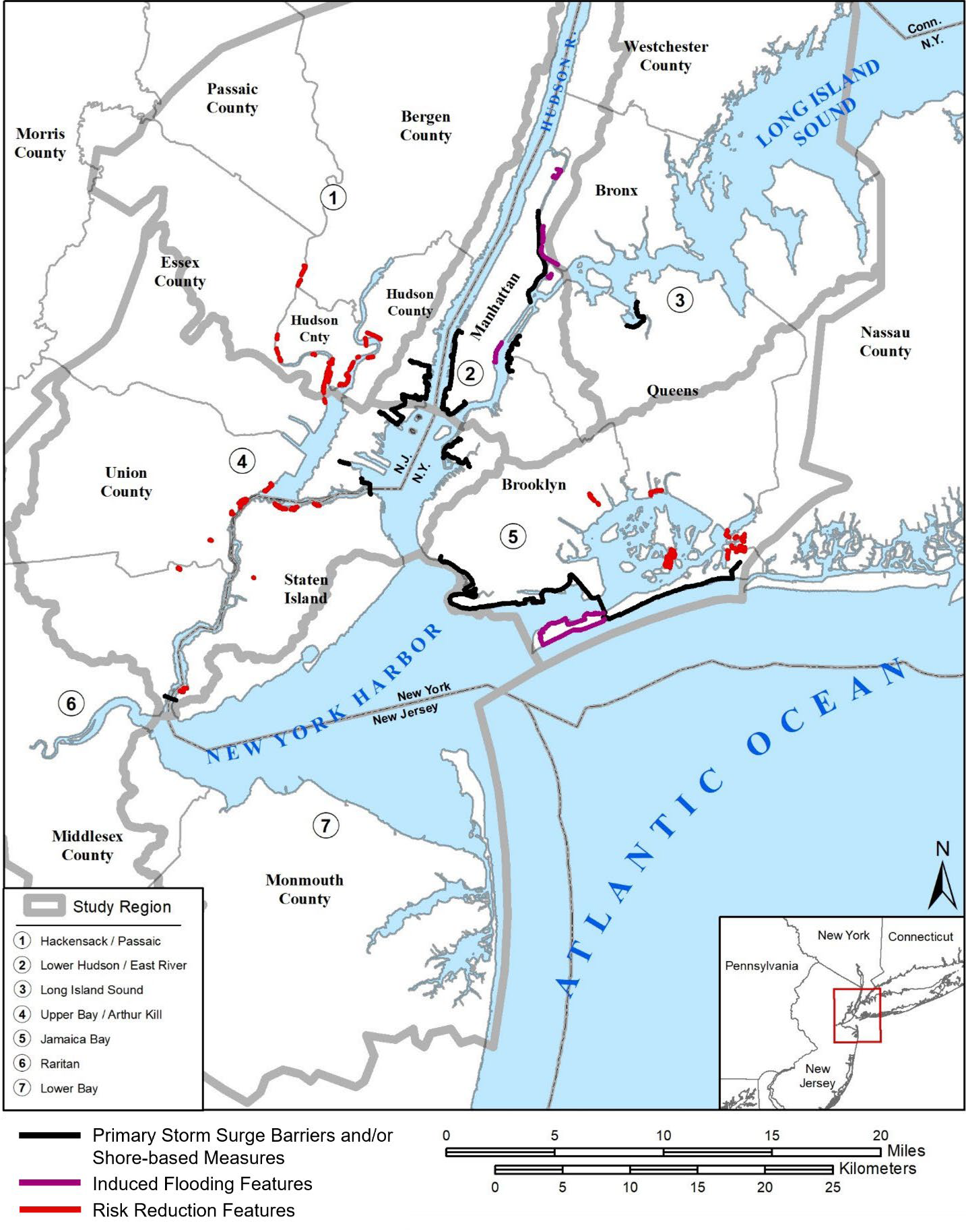

The coastal risk management alternative recommended by the Army Corps of Engineer as of January 2023. Map: USACE.

The HATS study presented multiple paths for the region and ended up recommending the middle of the road alternative. The Corps concluded that the proposed plan is the most cost-effective of the options presented, at least in how the Corps calculates things. It would protect the region from approximately 63% of damage risk for the 50 years after it is complete, engineers predict. Another plan, which would have prevented 96% of area risk, called for a massive miles-long storm surge barrier across the New York Harbor, but would have cost $112 billion, or twice as much.

Some of the remaining risk not addressed by the plan is alleviated by other state or local resilience projects, Wisemiller says, but a number of those projects are decades old and designed for different storm events. The Corps will need to evaluate them to see how much damage they are actually likely to prevent.

The public comment period for the massive climate resiliency project outlined in the HATS study — predicted to cost $52 billion if the Corp’s recommended plan goes ahead — was originally set to end this month, but has been extended until March 7, 2023.

After the public comment period and other reviews, statements, and reports will come another big hurdle: getting authorization and funding for the project from Congress. The Corps anticipates that will happen in 2030, with construction complete by 2044.

The Financial Shadow of Hurricane Sandy

The movement for a resilient New York metro area grew directly out of the experience with Sandy, says Amy Chester, managing director of Rebuild By Design, an independent organization that collaborates with jurisdictions. The storm was an unwelcome wake up call, causing $60 billion in property damage, 147 deaths, and resulting in a transformer explosion and power cut from downtown Manhattan for several days. That damage unlocked significant funds from the federal government, including from the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

That effort to use that money hasn’t always gone according to plan. In October, the New York City comptroller released a report asserting that the city had not spent 27% of the money it secured for restoration post-Sandy and that many ongoing projects are decades past their completion deadlines.

And Sandy’s catalyst has colored how and where resilience planning is focused in the region. In New York City, most coastal resiliency projects are located in places that were hit hard by the storm, rather than places that will be affected by future hazards, Chester says, in part because that’s where federal money can be used. In many projects, including HATS, focus has remained on storm surges, even though the New York area will likely face other hazards due to climate change.

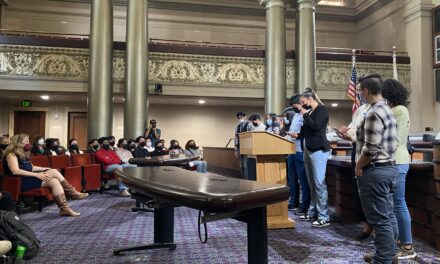

Early community outreach effort organized by Rebuild by Design after Hurricane Sandy. Photo courtesy Rebuild by Design.

“It’s very different from the Bay Area,” she says. “You’re starting from a place of building back from a storm rather than, ‘What are our climate hazards [ahead]?’”

With a growing understanding of climate change and its risks, Chester says it’s time to focus on that multi-hazard approach and build a comprehensive plan to protect the entire region. “Now that we’re in a different era, we all need to be shifting our dollars and attention pre-disaster, rather than post-disaster,” she says.

Community Pushback against Resiliency Project Details

Army Corps officials have said that their storm surge plan will need ample community feedback and buy-in to be successful. Wisemiller says the team has done several dozen engagements with community groups and other organizations.

The importance of community engagement has been particularly underlined by the blowup around Manhattan’s East Side Coastal Resiliency project. The project area runs along the East River on the Lower East Side, which is home to many towering public housing projects. Between homes and a riverfront park sits one of Manhattan’s largest highways, though it would be considered narrow almost anywhere else.

The city worked with community groups for multiple years to design measures to protect the area, but a feasibility study presented several tough and potentially insurmountable challenges for the community’s preferred plan. The city scrapped agreed-upon plans and decided on a different course of action that involved raising East River Park by about eight feet instead.

Advocacy groups, spearheaded by prominent artists like poet Eileen Myles, coalesced to try to stop construction and protect the park’s mature trees and well-known bandstand. After facing a lawsuit that was later dismissed, the city began construction in 2021, and the area is now closed off and dotted with heavy machinery.

Some money for construction needed to be used by 2022, adding to pressure on the city. But whether a more intentional effort to work with nearby communities may have prevented the controversy is unclear.

At the rainy December meeting for the HATS plan, New Yorkers had several lines of inquiry and comment. Questions touched on the possibility of more nature-based mitigation measures, environmental justice, and sprucing up some of the plan’s more austere infrastructure. The plan has not won favor with everyone. Some advocacy groups in particular have pushed the Corps to consider how the plan could disrupt existing ecosystems (see related story in KneeDeep’s East Coast mini-series).

Engineers and managers on the project appeared to welcome the feedback, emphasizing that they want community and stakeholder buy in. How much that feedback will change the trajectory of the project remains to be seen.

“We’re trying to use as many tools to get out to the vast communities that are in this broad study area as we can,” says Wisemiller. “As much as possible we’re looking to come up with a plan that addresses everybody, but we realize we’re never going to achieve that.”

Coordination Challenges across Jurisdictions

Kate Boicourt, director of NY-NJ climate resilient coasts and watersheds at the Environmental Defense Fund, echoes the need for a comprehensive regional resilience plan – beyond HATS – that will allow all actors to collaborate and protect the future from all of climate change’s hazards .

Current projects in the area, “are all separate, funded separately and have separate timelines,” she says. “Part of what you’re seeing is trying to coordinate disjointed efforts.”

New Jersey, New York, and New York City will have to decide if they want to pursue a project on their own or wait potentially 20 years for it to be included in the Corps’ plan, she says.

Although nowhere in the region is really as far along or as coordinated as she’d like, Boicourt says, New Jersey is the closest to creating the sort of plan she has in mind for the region. The state is focusing on resilience in specific areas in a way that she says could grow into an overarching vision.

The state, as part of its ResilientNJ planning program, currently has four action plans focused on different localities. It is also embarking on $700 million worth of flood and climate resilience projects using federal funds and matching contributions. Some of the state’s coastal projects are slated to finish around 2026, says Dennis Reinknecht, director of the division of resilience engineering and construction at the NJ Department of Environmental Protection. He says he coordinates near daily with the Army Corps.

New Jersey also has one of the country’s most prominent flood buyout programs, one that officials say they are hoping to use more proactively to address sea level rise. New York’s Environmental Bond Act, passed by voters in November, authorized $250 million for a voluntary flood buyout program of its own as part of $1.1 billion in spending on flood risk reduction and restoration.

New York has faced some criticism from residents, who sold their homes to the state as part of a more limited buyout program, for allowing the area to be redeveloped into a sports complex, New York Focus reported in October.

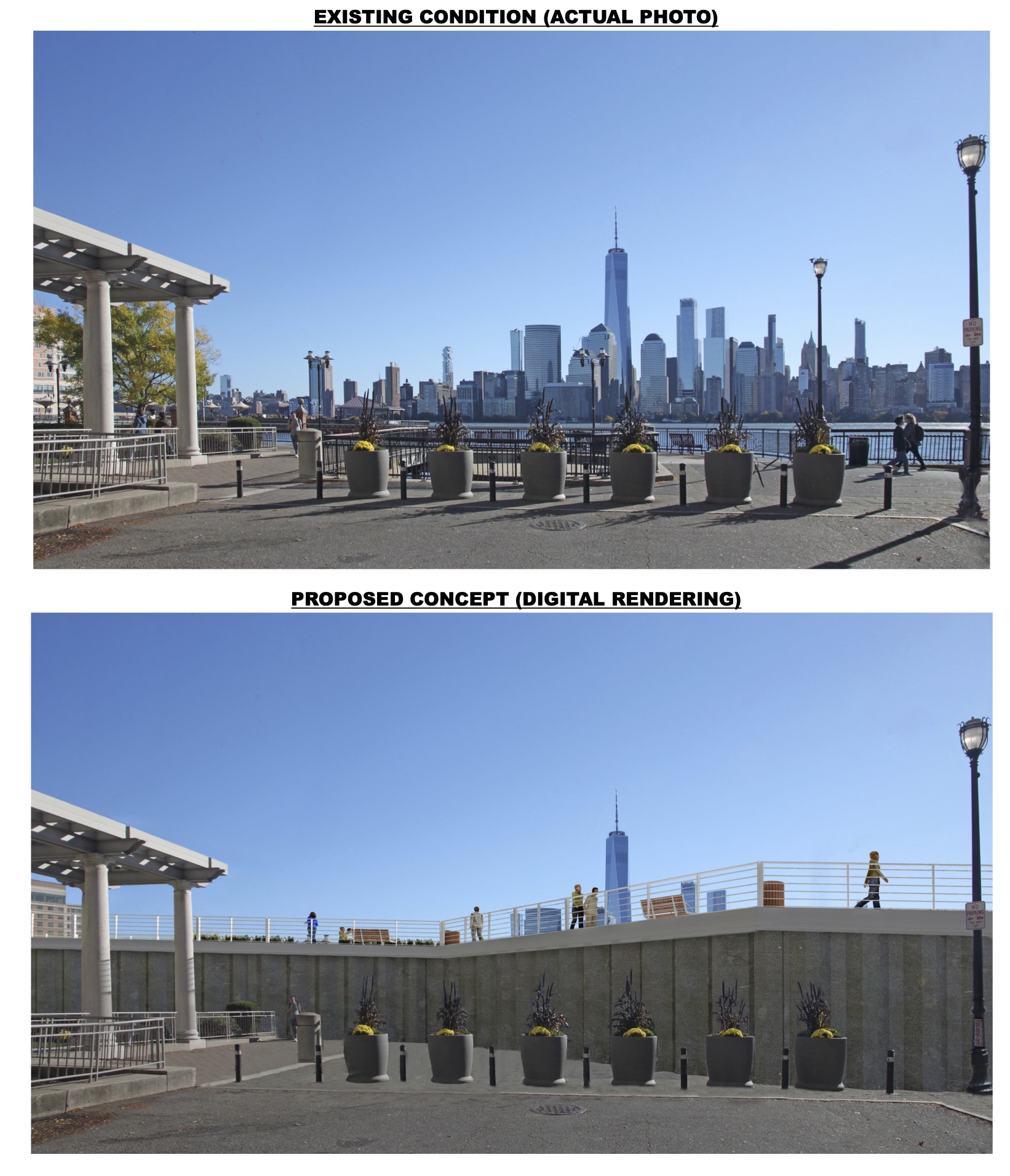

Before and after rendering of a raised walkway flood protection option for Jersey City. Rendering courtesy USACE.

New Jersey has its own challenges. The state has both major historic cities and small shore towns, and is the densest in the nation.

“We have 564 individual municipalities in New Jersey, all of whom have significant control over the land use decisions,” says Nick Angarone, chief climate resilience officer at the Department of Environmental Protection. “While it’s critical that we make sure that the ultimate vision here is consistent with what they want as a community, 564 individual governments does make it complicated to have that broader vision.” In comparison, the SF Bay Area is struggling to coordinate a mere 100 jurisdictions into its own regional plan, Bay-Adapt, by comparison.

The Corps’ involvement in the New York area has brought new and valuable resources to protect the region. But despite attempts by officials in every jurisdiction to coordinate, invest and plan, it’s unlikely that these current resilience efforts will keep the region totally free of risk as climate change accelerates.

But perhaps with enough meetings, engagement, coordination, and planning, officials will find it possible to get close. The sea won’t wait.

This story is one of Three Tales of Trouble and Triumph in the East Coast Fight Against Storm Surge.