Sonoma Taps Undeveloped Land in Climate Fight

“There are so many opportunities once we stop seeing our natural areas as threats and start seeing how they can be strengths if they are managed properly.”

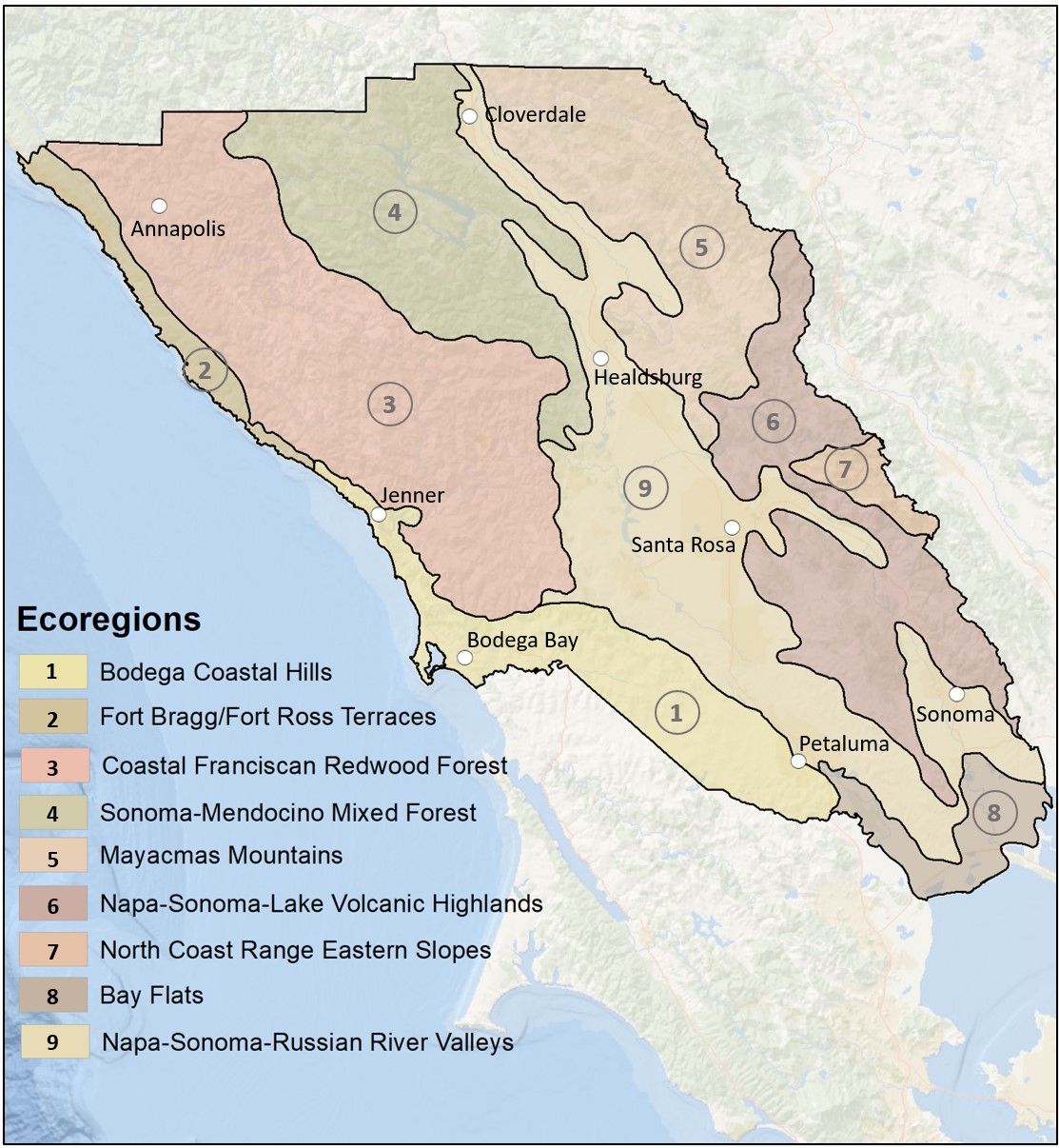

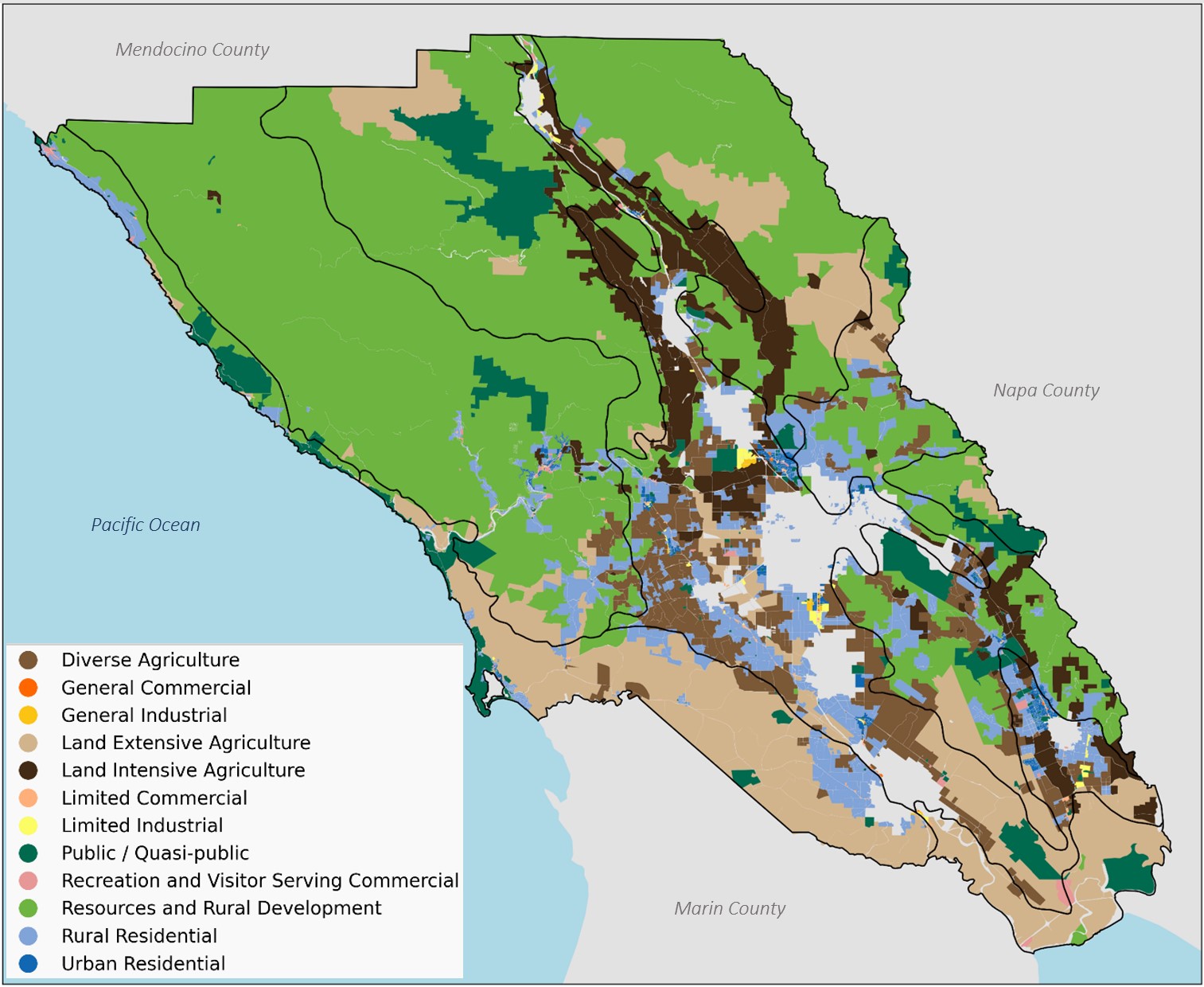

Seen from the sky, Sonoma County is remarkable for its vast swathes of undeveloped land. Most development sticks close to the corridor of Highway 101, as it snakes southward through the Russian River, Sonoma, and Napa river valleys, broadening into the alluvial Petaluma River Plain. This corridor, home to the bulk of the county’s flatland, also supports the most agriculture. On either side of this valley, the land buckles into mountains — ridge after forested ridge stretching to the Pacific ocean to the west, and toward Napa to the east.

Sonoma County’s natural beauty has long been treasured by residents and visitors alike. And yet, this land is buffeted by the growing impacts of climate change. Winter floods ravage low-lying areas, while droughts increasingly challenge wild ecosystems and agriculture. Wildfires can make the very air hazardous for weeks or even months at a time; add heatwaves and electrical outages, and life can become an ordeal for some and life-threatening for others, such as agricultural workers or the unhoused.

This fall, however, the County of Sonoma officially enlisted its abundance of undeveloped lands as a potential tool to fight the impacts of climate change. Last month, the county approved a “Climate Resilient Lands” strategy — becoming one of the first counties in the state to describe a clear vision for managing its acreage at a landscape level rather than in the traditional, piecemeal fashion in which each landowner (whether private citizen or public agency) operates independently.

“Sonoma County has already been on the frontlines of the disastrous impacts of climate change,” says Supervisor James Gore. “With a beneficial tool like this strategy to guide them, county departments, agencies, land managers, community organizations, and others can work effectively and efficiently with cohesion.”

The new resilient lands strategy lays out a process for working across public, private, natural, developed, and agricultural lands to conserve, manage, and restore as much of the county as possible — focusing on projects with the greatest potential for carbon sequestration, climate risk reduction, and biodiversity enhancement. The strategy also emphasizes equity and climate justice.

“There are so many opportunities once we stop seeing our natural areas as threats and start seeing how they can be strengths if they are managed properly,” says Lindy Lowe of Eastern Research Group, the consultants who oversaw development of the strategy on behalf of both the County of Sonoma Climate Action and Resiliency Division and the Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District, the two agencies which co-directed and funded the effort.

“The county has gone on the record stating that there is a commitment to natural and working lands as a climate partner,” says Lowe. “That’s not an insubstantial commitment for the county to make.”

Green Pastures, Too Many Fences

Sonoma County has long been known for its progressive environmental efforts, from local government to private citizens. However, none have taken a big-picture, climate-focused approach — until now.

“There are so many entities in Sonoma County that are already doing this type of work — which is great,” says Anna Yip, a climate analyst with the County of Sonoma. “We see our role at this stage as helping to coordinate new projects and fill gaps, while also acting as partners in existing efforts.”

The plan lays out not only goals, but also detailed descriptions of the county’s varied ecoregions; project concepts; and funding sources — essentially acting as a guide for anyone hoping to plan (and justify to funders) a new project that will promote climate resilience.

“Sonoma County could be a model for other parts of the Bay Area reluctant to do large scale resilience planning,” Lowe says.

To-Do List for Change

The new plan contains seven “priority recommendations” to advance its principles of landscape- and watershed-scale climate resilience. Priorities include climate resilience for those people most at risk; conservation, restoration, and connection of forests, grasslands and other natural areas; increasing the landscape’s ability to absorb water; and growing regenerative agricultural practices (holistic farming methods that, among other benefits, improve water and air quality, enhance ecosystem biodiversity, and store carbon).

The plan’s architects hope this clear mechanism for cross-jurisdictional collaboration will make funding for landscape-level projects easier to obtain.

“The strategy is deliberately structured to require multi-benefit projects,” Lowe says. “The hope is that early in the planning stages, project proponents will be pushed to see if they can do anything to address other issues, such as reducing flood or heat risk or restoring native plants, or if they need to involve additional members of the community. It is county-wide, landscape-scale planning.”

But what is a climate resilient landscape, exactly? The strategy contains specific metrics about targets to meet in different categories. Examples include: presence of pollinators or migration corridors; acreage of wetlands and restored wetlands; acreage, age, and diversity of forest lands; proximity of natural resource benefits to underserved and under-resourced communities; the health, safety, and capacity of workers to make a living wage; and the acreage of land using regenerative agriculture.

Hitting the Ground Running

Though its ink is barely dry, the plan is already being translated into action.

“We started jumping in to seeking funding early, because opportunities were popping up,” Yip says. As a result, the County has several projects already in the oven.

A $10 million grant to promote “carbon farming” — which maximizes long-term carbon sequestration while reducing agriculture-related emissions — was just awarded under the umbrella of implementing the climate smart strategy across Marin and Sonoma counties.

Over the next five years, the County, in partnership with the Carbon Cycle Institute and local resource conservation districts, among others, will coordinate this project working directly with farmers on successful carbon farming practices, as well as on enhancing a regional supply chain, tracking system and marketing campaign for “climate-smart agricultural products.”

“Marketing is a piece of it,” Yip says. “How do we market our work to consumers so they can make mindful purchases, knowing that the commodities they’re buying are not just local, or organic, but are also climate smart?”

Helen Putnam, a popular regional park near Petaluma, sits at the intersection of residential, agricultural, and publicly owned land. Photo: Jacoba Charles.

Creating financial support systems for climate smart farming is essential, adds Caiti Hachmyer, owner of Sebastopol’s Red H Farm and a stakeholder advisor on the Resilient Lands Strategy.

“The kind of agriculture that will help build climate resiliency is very investment intensive,” Hachmyer says. But this investment is vital, she adds, because farmers and farm workers are on the front lines of climate change. “In many ways, we are primary land stewards.”

Listening to More Voices

Sonoma County is also pursuing funding for a community-led approach in developing four climate-resilient green corridors in four underserved areas. Each community will design its own corridor, with support from local advocates and technical advisors. (The project involves seven local nonprofits and community advocates, including Greenbelt Alliance).

“These are communities that haven’t had the benefit of nearby greenspaces, and they also haven’t had a strong voice in the land use decisions that shaped them — this project gives them both,” says Barbara Lee, Director of Climate Action and Resiliency for Sonoma County. “It’s an exciting project. The grant will also help them develop skills to seek funding for their designs, and we have identified matching funds for every dollar they raise.”

Sonoma farm workers challenged by fires and the pandemic rally to support language justice, hazard pay, disaster insurance and a formal evacuation zone. Photo: John Burgess, The Press Democrat.

The green corridors project fits into the county’s new strategy by bringing the benefits of resilient lands to residents who are most vulnerable to climate hazards.

“In developing the strategy, Sonoma County welcomed participation from a wide diversity of residents and people who own, manage, and work on the land,” says Lee. These perspectives, she says, helped the project team hear voices not often heard in policy discussions, such as linguistically isolated farmworkers or the unhoused. The project will also include community-defined job skills training.

This is a deliberate move away from how plans have traditionally been enacted in the past, Lowe says.

“There is a history of people coming in and deciding what a project will be, without community residents being notified until projects are well-developed,” says Lowe. “If their response is, ‘but we don’t want that, what we really need is this,’ then it is often already too late.”

Going forward, the County also plans to collaborate with local tribal leaders to elevate and center traditional knowledge and practices, and explore opportunities to co-manage land resilience, according to Lee.

Envisioning Better

From the Fort Ross Terraces to the Mayacamas Mountains, the Resilient Lands Strategy was made to be applied at all levels — and scaled up, where possible.

Project concepts offer rough blueprints for future work, including specifying where they would be most suitable. Projects that might benefit the rugged, windswept coastal bluffs won’t help cool 100-degree heatwaves in Santa Rosa, but both are important for benefitting the county as a whole.

“We’ve done this legwork to show that these actions will lead to strong impacts,” says Yip.

“There’s already a lot of committed people in Sonoma County doing amazing small-scale projects,” Lowe says. “If you take these efforts and apply them at the county scale, you get some pretty significant risk reduction, climate benefits, and community benefits that really add up.”