San Mateo County Pieces Falling Into Place

“This isn’t a project that any of us can undertake in a vacuum.”

To a traveler arriving in the Bay Area by air, the vulnerability of San Francisco International Airport (SFO) to rising seas is alarmingly apparent. Gazing out of the window as the plane touches down on a runway that juts into San Francisco Bay, the traveler can see the waves lapping just a few feet below.

“When you look at future sea level rise scenarios, the entire airport property, runways and facilities, could be inundated,” says SFO’s Doug Yakel. The existing protection system, which consists of vinyl sheet pile walls, concrete seawalls, and concrete-capped earthen berms, “was designed to protect against wave action during stormy weather. It really wasn’t designed to protect against an aggregate increase in the level of our seas.” Yakel notes there are also entire sections of the airport waterfront with no protection at all, including the water treatment facility and the US Coast Guard station.

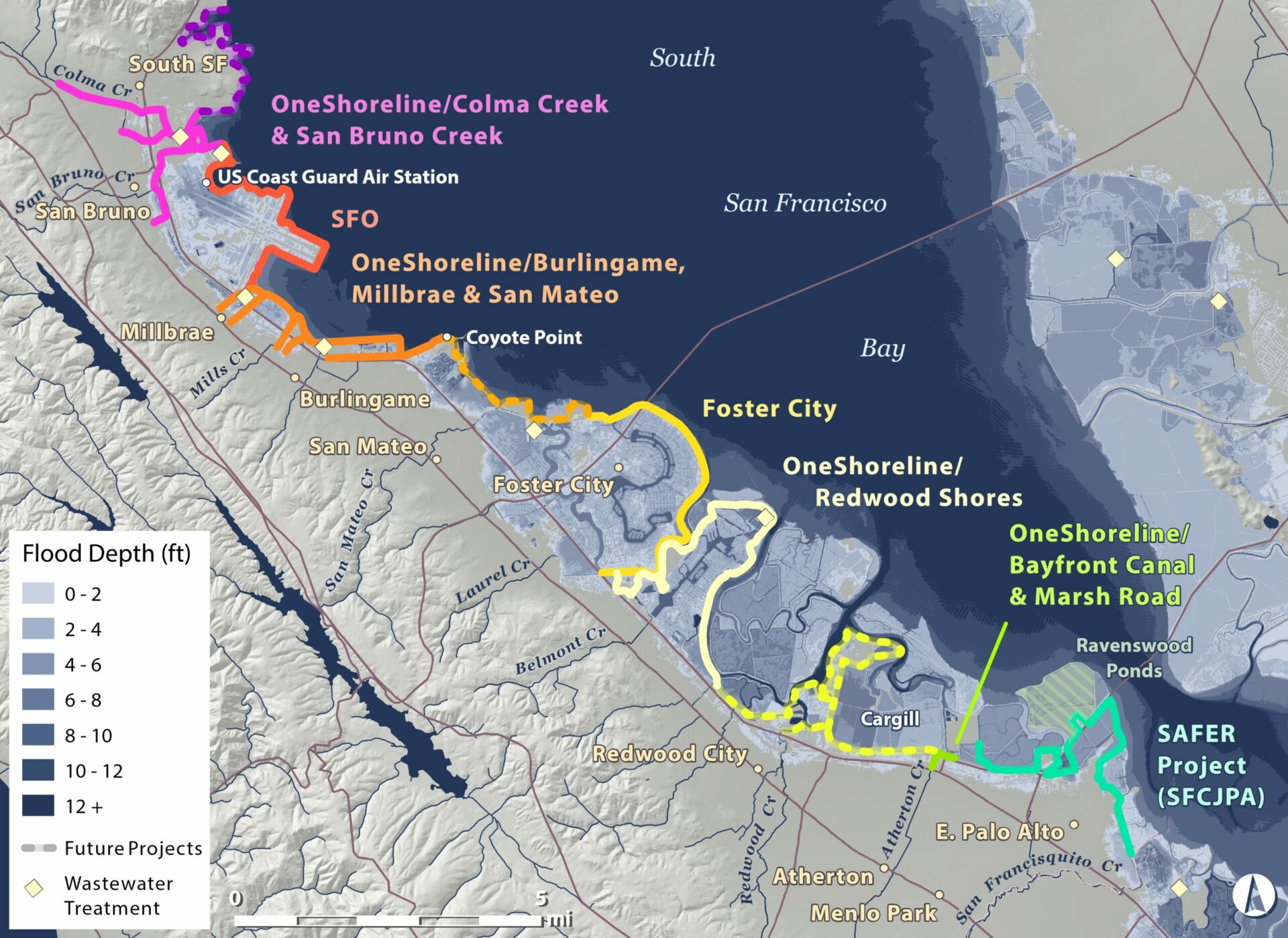

But a plan to fortify the airport, which encompasses eight miles of Bay shoreline between South San Francisco and Millbrae, is gaining momentum. In October, the San Francisco Planning Department released a Draft Environmental Impact Report for SFO’s Shoreline Protection Program, which will protect the airport against an extreme 100-year tide and 42 inches of sea-level rise. More than that, the plan is shaping up to become a critical link in a chain of resilience projects strung along the county’s bayshore.

Assemblymember Kevin Mullin, D-South San Francisco, helped secure $8 million from the state budget last year, half of which will help design shore protection for Burlingame and Millbrae. Photo: Corey Browning, San Mateo Daily Journal

The proposed airport protection system will feature reinforced concrete and steel sheet pile walls of varying heights. According to Yakel, SFO expects to issue general revenue bonds — a form of municipal bonds — to cover the anticipated $590 million cost of the project. The current schedule calls for the project to be completed by 2035.

Planners also intend to tie the new flood protections into anticipated projects to the north and south now being spearheaded by San Mateo County’s Flood and Sea-Level Rise Resiliency District (also known as OneShoreline). Last spring, design and permitting work got underway on a OneShoreline project that would protect the Millbrae and Burlingame sections of the shoreline to the south of the airport. Both cities had previously independently studied their shoreline vulnerability and resilience strategies; through the new project, the cities are partnering with OneShoreline, the airport and the bay-side landowners on a coordinated approach.

“We’re worried about shoreline overtopping under a scenario of a 100-year tide plus six feet of sea level rise, which is equal to about ten feet above today’s high tide,” says OneShoreline CEO Len Materman, adding that the project will also address flooding on five local creeks.

“It’s such a low lying area that with with sea-level rise, just the daily tides will go up [the creeks] well past Highway 101,” says Materman. Traditional levees and flood walls would require tide gates and pump stations at every creek mouth. “That becomes a very difficult and costly project, so we’re exploring other strategies,” including nature-based ones and working both onshore and offshore, he says.

Evolving multi-jurisdiction adaptation strategy for the San Mateo County bayshore, with grey zone indicating projected sea-level rise. Map: Amber Manfree.

Materman says that although the current project is only looking at the Millbrae-Burlingame shoreline, “we want our project to be something that can be extended to Coyote Point in the City of San Mateo, which is high ground.”

Down the road, OneShoreline also expects to develop a project from San Bruno Creek on the northern border of the airport to South San Francisco, where it would connect with an ambitious watershed-wide effort to restore and adapt Colma Creek. Together, the two OneShoreline projects would obviate the need for SFO to build sea level rise protection along Highway 101.

“We’ve always understood the importance of collaborating with our neighbors to the north and south along our shoreline,” says Yakel. “This isn’t a project that any of us can undertake in a vacuum. It’s really important for us to understand how this links in with other communities to ensure that we really have a cohesive solution at play.”

The effort to coordinate all along the county shoreline doesn’t stop there. At the southern end of the county, OneShoreline is coordinating with the San Francisquito Creek Joint Powers Authority (JPA) on the SAFER Bay Project, a regional program that aims to protect the Bay shoreline from the northern border of Menlo Park to the southern border of East Palo Alto.

This June, the JPA received $1 million from the San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority for environmental documentation and design work for the project, which, when completed, will protect properties — including many homes, and critical infrastructure — and restores or enhances marshes in East Palo Alto and Menlo Park. The project, which has been in the works since 2013, will connect with the JPA’s flood protection project at San Francisquito Creek, which was completed in 2019.

“We’ve been at this for a long time,” says East Palo Alto Mayor Ruben Abrica, who serves as chair of the Joint Powers Authority’s Board. “We have always been keenly aware of the potential for flooding from the Bay itself, even without sea level rise.”

“This is an incredibly complex project,” says the authority’s Margaret Bruce, at least in part due to the number of jurisdictions and agencies involved. The authority is tapping the Bay Area Restoration Regulatory Integration Team to help coordinate permitting for the project.

On the Redwood City border, the SAFER Bay project will also connect with OneShoreline efforts, including a recently completed bayfront canal and channel in Atherton. This project takes fresh water out of the canal during high flows and sends it to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Ravenswood ponds.

Atherton segment of OneShoreline project before and after completion.

“That was a good proof-of-concept project for a new regional agency,” says Materman. Local jurisdictions started planning the project, which provides flood protection to five mobile home parks, in 2009, but it was not close to construction when OneShoreline was formed in January 2020. “They handed us the design and asked us to deal with it.”

OneShoreline put together a $10 million funding agreement with the cities and County and completed the necessary environmental documents, land rights, and permits. “We started construction summer of 2021 and now it’s done,” says Materman.

“The fact that the cities were trying to get it off the ground for eleven years, and we’ve completed the whole thing in a year and a half, I think speaks to why focused regional approaches to climate adaptation along the shoreline make sense,” says Materman. “Because if a project crosses borders, things get super complicated.”