Safer at School from Wildfire Smoke?

When wildfire smoke fills the air, is it safe for students to go to school? “My son has asthma, so when it’s smoky I really want to know what his day is going to look like,” says Nancy Metzger-Carter, a teacher in Santa Rosa. Almost half of the top 20 largest fires in California history have happened in the past three years, overlapping with a pandemic that stretched schools to their limits. In response, the Bay Area Air Quality Management District has just finished retrofitting 16 vulnerable elementary and middle schools with high-performance air filtration systems to get ahead of future fire seasons. “After homes, schools are the second place where kids spend the most time,” says Stanford doctor Lisa Patel. “And so when we think about creating safe buildings for kids to be in, we should be focusing on those two buildings.”

Extremes-in-3D

A five-part series of stories in which KneeDeep Times explores the science behind climate extremes in California, and how people and places react and adapt.

Supported by the CO2 Foundation and Pulitzer Center.

FULL READ

Safer at School from Wildfire Smoke?

For Nancy Metzger-Carter, a high school teacher in Santa Rosa and mother of two children, ages 10 and 14, she has wondered during wildfire events what sort of impact the smoke is having on her kids, and whether or not it’s safer for them to be at home or at school.

“My son has asthma, so when it’s a smoky day I really want to know what his day is going to look like,” says Carter. “There was a big amount of confusion. Like, what is the guideline? Where is the line where we say it is safe for kids to be outside? Where’s the line where it’s not?”

It wasn’t until after the Tubbs fire in 2017, which was part of the Central LNU Complex that ravaged Napa, Sonoma and Lake counties, that Nancy felt like wildfires weren’t a random occurrence, but something that would become part of the seasons.

“It was one of my first introductions to wildfire as a part of our lives. I think most of us hadn’t really considered it before. And once the Tubbs fire passed… you know, we’re still healing from that trauma,” says Metzger-Carter, a campaign leader for Schools for Climate Action.

California has been subjected to some of the most extreme wildfire seasons in recent years. Almost half of the top 20 largest fires have occurred since 2020, with six of those fires in the top ten. With that, wildfire smoke has had a drastic impact on people’s health, prompting state agencies to look towards how school settings are mitigating these impacts of harmful particulate matter on children.

However, some areas are more affected than others.

In 2018, the Bay Area Air Quality Management District identified 12 schools in communities disproportionately impacted by air pollution in Alameda, Contra Costa, and San Francisco Counties to receive funding to install high-performance air filtration systems to alleviate these impacts (a few years later the district added four more schools to the list). The funding, a $2 million supplemental environmental project award, was provided by the California Air Resources Board.

Gloomy, smoky skies engulf Bay Area school in 2020. Photo: Maurice Ramirez.

“Schools without a proper HVAC system are forced to rely on opening their windows for adequate ventilation. Therefore, students could be exposed to higher air pollution concentrations depending on their location and proximity to sources of air pollution,” says Juan Romero, a spokesperson for the Bay Area air district.

Romero adds that many schools in the Bay Area are located near freeways and roads, so students are also exposed to higher levels of PM 10 and PM 2.5 from tailpipes, exacerbating health effects from bad air quality of any kind.

The 16 elementary and middle schools were identified by considering characteristics such as the total enrollment at the school, the number of students on a free or reduced lunch program, and proximity to sources of diesel particulate matter.

“We reached out to school districts and the superintendent, and shared information about the program,” says Aneesh Rana, a Senior Staff Specialist in the Community Engagement & Policy Division with the air district. “If they were interested in participating in the program once we got confirmation we would go out and [look at] what kind of equipment needed to be installed.”

The Bay Area Air Quality Management District also partnered with the IQ Air Foundation, a nonprofit that helps improve access to air quality data, environmental literacy, and technology to assess and improve school infrastructure.

HVAC and air filtration systems give schools more options for mediating bad air, germs, wildfire smoke, and heat. As of February 2023, all 16 Bay Area schools have received the retrofit. Grants also cover five years of maintenance and some of the filters.

EXTREMES-IN-3D

A five-part series of stories in which KneeDeep Times explores the science behind climate extremes in California, and how people and places react and adapt.

Series Home

Click here to enter

Supported by the CO2 Foundation and Pulitzer Center.

Schools as Safe Havens

Other than the home, kids spend a majority of their time at school: on average, over six hours a day in the classroom, and over 181 days a year. Schools are increasingly recognized as community shelters in cases of extreme heat, seen as the deadliest killer among extreme weather events, as well as gathering spaces for those who don’t have proper ventilation in the home.

One school now being converted to a safe haven through the air filtration upgrade program is Hoover Elementary School in West Oakland. For the kids at Hoover, their campus is surrounded by freeways, sitting near the junction of the MacArthur and the Grove Shafter Freeways. Just a couple of miles West sits an industrial area along the Oakland harbors, which wraps around to the I-80 bridge that crosses over to San Francisco.

“For the neighborhood, air quality is an issue. We have a lot of students who have asthma and the families will say that it’s better when they’re in school,” says Hoover’s Principal Lissette Averhoff. “We just had a three-day weekend and a student was hospitalized because when he’s home, his asthma acts up.”

Busy streets and freeway exhaust near Hoover Elementary, Oakland. Photo: Katie Rodriguez

According to research published in Nature Sustainability in 2022, the added layer of wildfire smoke can hurt learning outcomes, and has been linked to lower test scores. The study looked at threats from increased frequency and severity of wildfires, analyzing standardized test scores from 2009–2016 for nearly 11,700 school districts across the United States. The impact on test scores almost doubled when students were exposed to heavy smoke during the school day.

Dr. Lisa Patel, a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Stanford University who has focused much of her research on the links between children’s health and environmental issues thinks that public resources should be investing in ensuring that our school buildings are keeping kids safe, and that it should be our public charge.

“After homes, schools are the second place where kids spend the most time,” says Dr. Patel. “And so when we think about creating safe buildings for kids to be in, we should be focusing on those two buildings. We shouldn’t be willfully sending our children into unsafe spaces.”

Learning Curve

While California tries to make schools safer places for students to breathe, for teachers in areas that experience wildfires more frequently, more work needs to be done. Vonnell Jarrell, a history teacher at Folsom Middle School in Sacramento County has noticed a lack of focus among his students during wildfire events, likely due to both their physical responses to the smoke and the mental trauma of a fire making them feel unsafe. He claims it has been a barrier for not only the students, but the teachers as well.

“Students get headaches. Their mind is not on learning, which then makes it that much more difficult to teach. The entire chain is disrupted,” he says.

Recent research points to wildfire smoke being ten times more toxic than regular forms of air pollution.

According to Lil Milagro Henriquez, founder of youth-centered climate resilience organization Mycelium Youth Network, young students are deeply connected to their bodies and their developing respiratory systems. Feeling like they can’t talk to adults about their different experiences with toxic smoke not only creates a culture of distrust with adults, but it also leads to feelings of anxiety and depression.

Joshua Harris, who works at Foothill Ranch Middle School, also in Sacramento County, echoes this sentiment, but especially as it pertains to adults who have more control over how schools respond to wildfires.

“My students think the district doesn’t care about them,” he says, mainly because they don’t understand why the school district makes them go to class on smoky days. “Adults don’t explain it to them, so in the future they go back to that moment, and carry it with them in other interactions with district members.”

After lots of confusion around some schools in Sacramento being closed and others remaining open following large wildfires, the county finally created a wildfire smoke response plan as of September 2022. While it isn’t mandatory, it recommends that schools move recess, athletic practices and physical education classes indoors when the Air Quality Index (AQI) reaches 200. California guidelines for how schools should respond to wildfire smoke were last updated in 2019.

Technology & Monitoring

The goal for the 16 Bay Area schools using the supplemental environmental project award funds was to achieve MERV 16 level air filtration. MERV, also known as “Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value,” is a rating system for the effectiveness of filters at trapping airborne particles. The range is from 1-16, 16 being the most effective.

In order to achieve this high level of filtration, the older schools that may not have had an existing HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) system required wall-mounted or mobile stand-alone units.

Monitoring device. Photo: Katie Rodriquez.

Schools that already had HVAC systems only needed to modify filter intake compartments in order to accommodate the newer MERV 16 filters.

Before deciding how to place this new technology in a school, IQ Air first factored in the layout of the physical building, as well as the quality of air outside the buildings, using a term they refer to as “establishing baseline.”

“Establishing baseline involves measuring outdoor air – a good measurement of how good your air quality [indoors] is going to be to compare it to outdoor air,” explains Glory Hammes, CEO of IQ Air. “There is one device we place outdoors and then, with regards to inside our schools, [we place] devices in a representative amount of classrooms.”

Each city and school district exists in different micro-climates and geographic conditions, requiring a tailored approach. Unlike the cooler Bay Area, for example, most Sacramento area schools already have HVAC systems which were updated in 2020 during COVID. The Sacramento Metro Air District has tools and protocols to help schools and buildings near to air toxics limit exposure. In the Sacramento Unified School District, the highest level of filtration is MERV 13.

Deploying Dollars, Band-aids and Local Knowledge

Across the federal stage, acknowledgment of the domino effects of wildfire smoke inhalation on kids in the classroom environment is growing. In April of 2022, the Biden administration announced a half a trillion dollar investment in federal grants to make infrastructure improvements at K-12 public schools, including ventilation. The Environmental Protection Agency recognizes schools as safe spaces for cooling centers protecting communities from extreme heat, seen as the deadliest killer among extreme weather events, as well as for gathering spaces for those without good ventilation at home.

While this is a step in the right direction, climate advocacy groups like Mycelium Youth Network believe that in order for schools to fully become spaces for students and others to feel protected and safe, even more than the latest technology is necessary.

“HVAC systems are band-aid solutions,” Henriquez says. “The real solution to climate change is multi-pronged and starts with the wisdom and ancestral knowledge held in black and brown communities. We have to learn to live with the land and [fire].”

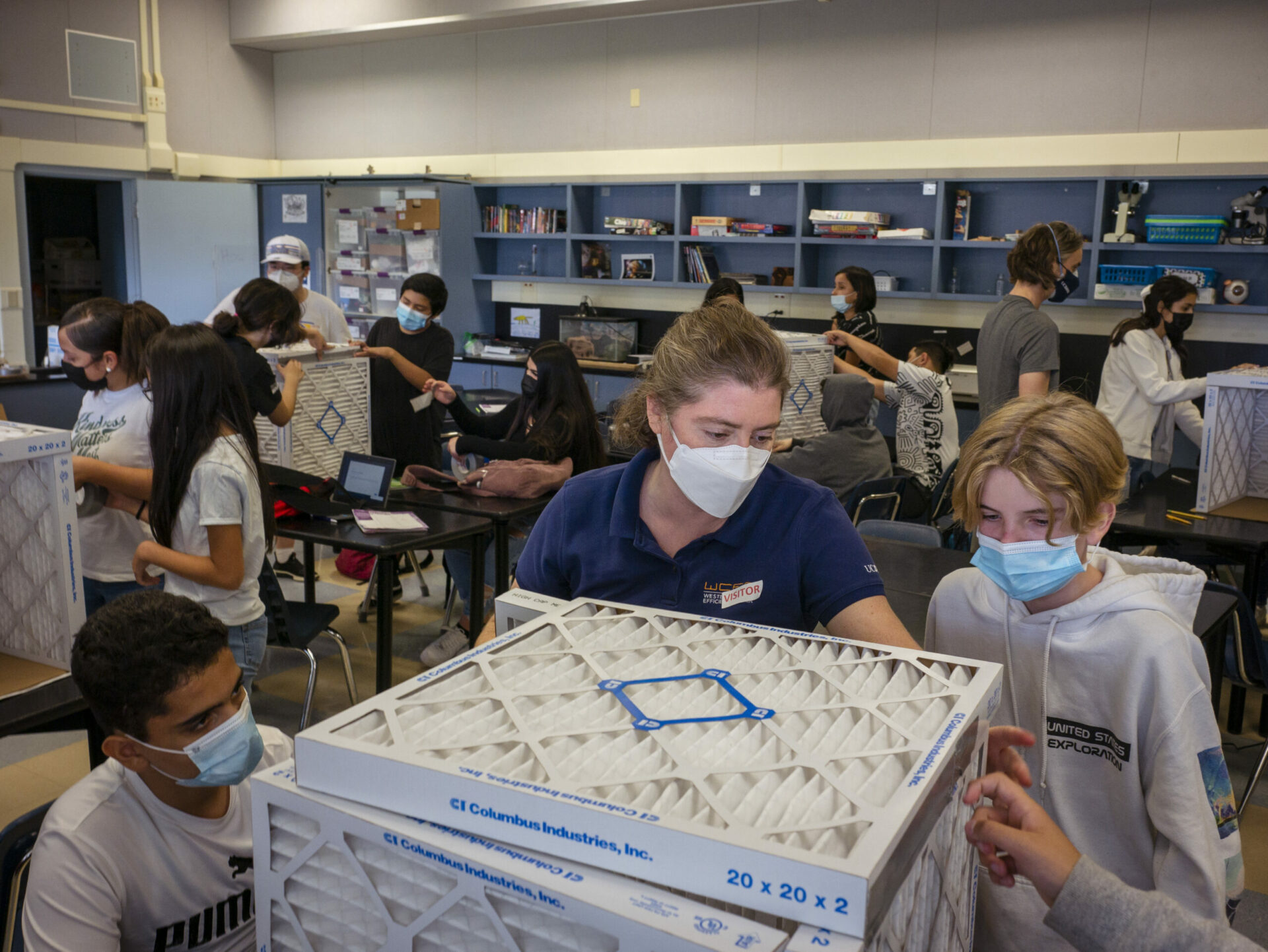

Students in Sacramento high schools learn how to build do-it-yourself air filters. Photo: Paul Fortunata.

In addition to upgrading HVAC systems, this “multi-pronged” solution requires efforts both inside and outside of schools, such as tracking air quality, providing workshops for families, DIY systems for individual homes, pushing local elected officials to address air quality issues, bringing plants into classrooms, permaculture, creating curriculum and defensible spaces, cultural burns, connecting with native practitioners, and ultimately cultivating careful relationships with wildfires.

While Californians ponder all options, the interim focus at the state level seems to be on more money for upgrading school infrastructure to be more climate resilient and for supporting on-site staff to guide schools into the new normal.

Santa Rosa teacher Nancy Metzer-Carter, part of a statewide initiative called CA Climate Ready Schools, stresses that school districts already have their hands full addressing things like mental health, teacher shortages, and learning gaps from the pandemic:

“Here in Northern California, the last two years have been relatively calm with no big smoke events so the urgency of upgrading school HVAC systems can be forgotten. But the next event is not an if, but a when? It’s essential more state funding for zero-emission HVAC upgrades for schools is passed and held in the highest priority for student health and well-being.”

EXTREMES-IN-3D

SERIES CREDITS

Managing Editor: Ariel Rubissow Okamoto

Web Story Design: Vanessa Lee & Tony Hale

Science advisors: Alexander Gershunov, Patrick Barnard, Richelle Tanner

Series supported by the CO2 Foundation.

Special acknowledgements for Safer at School?

Jasmine Hardy is not only a reporter based in Sacramento, but also works in after-school programs there. In addition, she grew up going to school in Oakland.

Sierra Garcia contributed to this story.

Banner photo is Hoover Elementary in West Oakland by Katie Rodriguez.