Pricing Climate Risk

Economics has been called the dismal science. That label might seem to apply in spades to a novel sub-specialty: the art of pricing the risks of climate change, a concern not least to the insurance industry.

To get the basics, you could do worse than to talk to Dag Lohmann. Physics at the U. of Göttingen in Germany. Post-doc in civil engineering at Princeton. Six years with the National Weather Service. Almost eight with a leading risk modeling company, RMS. Ten, and counting, with his own Berkeley firm, KatRisk LLC, focused on various kinds of flooding. Oddly, at the end of that conversation, you might come out feeling just a little less dismal.

Insurance shifts costs from individuals to groups. It also shifts costs from after an untoward event to before. Your auto insurance shares your risk with millions of other drivers, giving each a small load now to protect each against a possibly crushing burden later. Flood and fire insurance, ideally, should work the same way; but the creeping change in climate is changing their arithmetic.

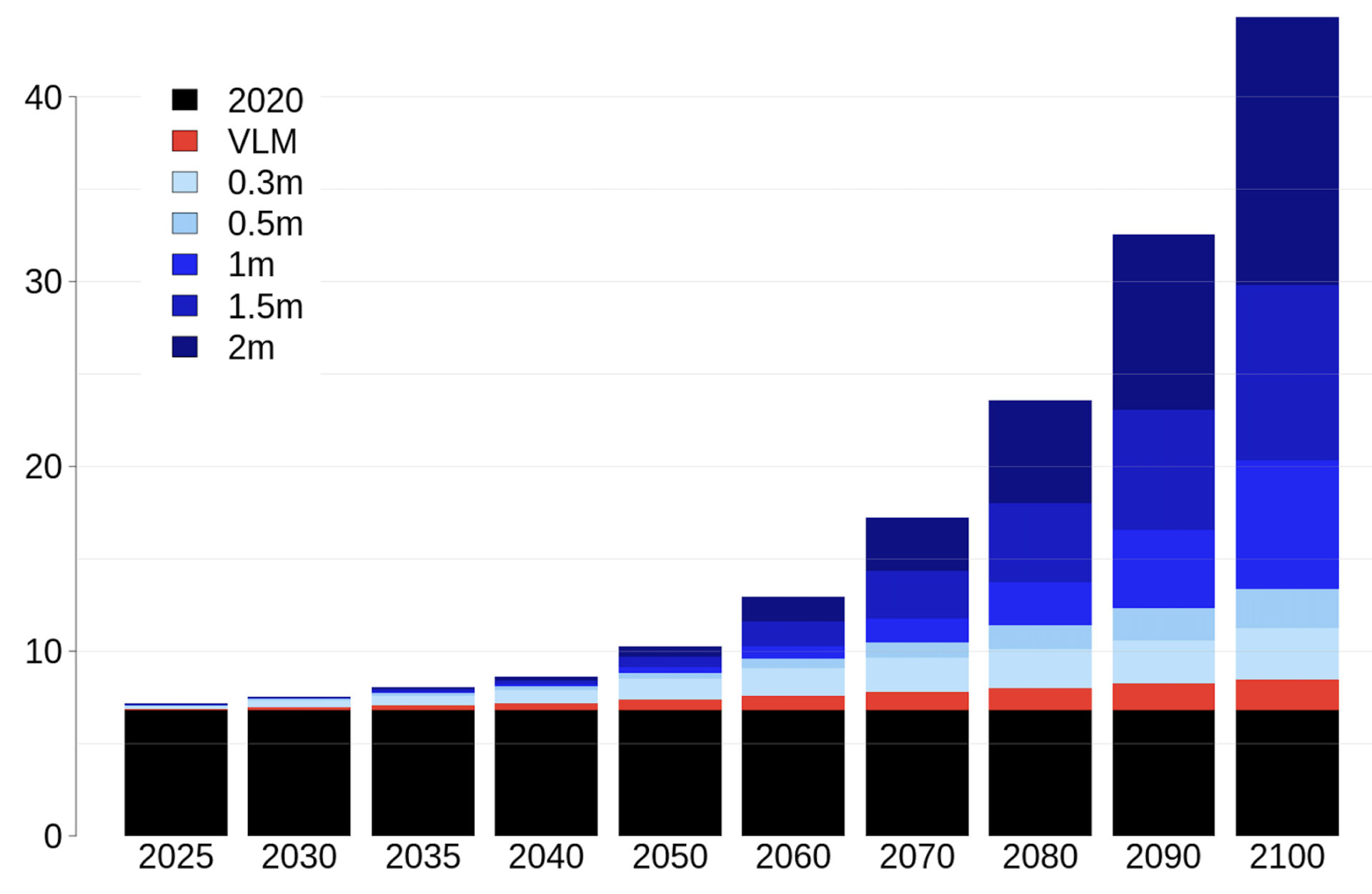

Just how much, and with what financial consequences, is Dag Lohmann’s province. His team knows and applies the latest science. “We’re the middleman between scientists and insurers,” he says. “We rely on research and data from universities and government labs, but do our own simulations.” Lohmann can, for instance, quantify the creep in storm surge losses caused by sea level rise. In the U.S. these are climbing by about half a percent per year, he says, a rate that is sure to increase.

The news is less bad for inland flooding and those seeking insurance against it. Premiums vary wildly nationwide. Some properties should be paying more than they do now for their policies, but many should actually be paying less. Subtle assessments can bring fairer pricing; they can also help in the design of protective measures. Financial players of several kinds may find it prudent to invest in prevention, reducing the cost of cure.

Like big fleas feasting on littler fleas, insurance companies also buy insurance, to cover them against the occasional catastrophic loss; specialized re-insurance companies, with names like Swiss RE and Munich RE, exist to fill this role. A further wrinkle has recently emerged: the packaging of these reinsurance policies as bonds sold to investors—what the trade calls securitization. People with money buy these “catastrophe bonds,” (cat bonds for short), taking the risk of the occasional bath (a risk to be assessed by analysts like Lohmann’s) in return for considerable annual profit.

Other Recent Posts

Assistant Editor Job Announcement

Part time freelance job opening with Bay Area climate resilience magazine.

Training 18 New Community Leaders in a Resilience Hot Spot

A June 7 event minted 18 new community leaders now better-equipped to care for Suisun City and Fairfield through pollution, heat, smoke, and high water.

Mayor Pushes Suisun City To Do Better

Mayor Alma Hernandez has devoted herself to preparing her community for a warming world.

The Path to a Just Transition for Benicia’s Refinery Workers

As Valero prepares to shutter its Benicia oil refinery, 400 jobs hang in the balance. Can California ensure a just transition for fossil fuel workers?

Ecologist Finds Art in Restoring Levees

In Sacramento, an artist-ecologist brings California’s native species to life – through art, and through fish-friendly levee restoration.

New Metrics on Hybrid Gray-Green Levees

UC Santa Cruz research project investigates how horizontal “living levees” can cut flood risk.

Community Editor Job Announcement

Part time freelance job opening with Bay Area climate resilience magazine.

Being Bike-Friendly is Gateway to Climate Advocacy

Four Bay Area cyclists push for better city infrastructure.

Can Colgan Creek Do It All? Santa Rosa Reimagines Flood Control

A restoration project blends old-school flood control with modern green infrastructure. Is this how California can manage runoff from future megastorms?

San Francisco Youth Explore Flood Risk on Home Turf

At the Shoreline Leadership Academy, high school students learn about sea level rise through hands-on tours and community projects.

When Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast in 2005, a specialized fund called Kamp Re took a heavy hit and dissolved. Its investors lost about three quarters of their money. But Kamp Re did pay its insurance company clients, and those companies in turn paid the individual policy holders. In a sense, the system can be said to have worked, shifting cost from those least capable to those most capable of paying.

Katrina dramatized the need for better risk assessment, but it did not dampen the rise of “cat bonds.” The National Flood Insurance Program (the nation’s largest single-line insurance program) issues quantities of these, and KatRisk is right there, acting as “calculation agent” for the last five rounds of bonds. The company has thus helped shift more than $1 billion in hurricane risk from NFIP to the capital markets, Lohmann says.

In California, far from hurricane country, the flood risks tend to be more chronic than dire. The typical problem here is different: too few of us can find affordable insurance, making post-disaster recovery hard. The community benefit insurance concept (see “Overhauling Insurance” below) is a possible fix, applicable also to fire. Earthquakes are another matter, where the catastrophe bond concept might apply.

So here is an industry, not known for altruism, doing its part to wrestle with huge societal problems. This is surely encouraging, up to a point. But as climate weirdness mounts, there will be more and more situations where the insurance model is simply obsolete. “Over what time frames,” Lohmann asks, “might insurance not be possible anymore in parts of Louisiana or Florida?”

The story has its dismal side, after all.

Average annual loss to storm surge from Atlantic hurricanes in billions of dollars under different global sea level rise scenarios in meters by the year 2100. The analysis translates government data (the latest NOAA sea level rise projections) into financial losses. (VLM = vertical land movement, largely from Louisiana and Florida sinking.) Source: KatRisk.