Pajaro Residents Weigh In on How to Use Climate Funds

As his mother chats about housing costs, the stroller-bound baby watches the next table over, where a flour tortilla is folded over into a quesadilla atop an electric cookstove. They’re among the first attendees of the three-hour Climate of Hope Fair in Watsonville, an event organized by the nonprofit Regeneración Pajaro Valley in late September for the agricultural community on the Central Coast to learn and share ideas for allocating climate funds from the California Strategic Growth Council.

People filtering into the room spin a wheel which lands on one of a dozen conversation starters, from energy costs to park access to transportation. The staffer at this station takes notes on large sheets of paper taped to the walls. As the afternoon progresses, she has to add more sheets of paper as popular topics fill up. Talking to folks at the event, she often draws on examples from Mexico to help jog people’s ideas, like public combis (cheaper, van-like local buses), or mixed-use zoning where corner stores and neighborhood housing blend together.

The event is prepared to welcome everyone: a volunteer supervises children while they play and color so their parents can roam; a food stand offers complimentary potato flautas next to ruffled greens, bright and oddly shaped bell peppers, and other assorted veggies in crates, which a volunteer proudly tells me are free to take home.

Eventually, the woman and her son are directed towards tables with hand-drawn maps of both Watsonville and Pajaro, where they’re encouraged to add sticky notes to exactly where in their neighborhoods they want to see changes. Anyone who visits all the stations for discussing community climate ideas with Regeneración staff can enter a raffle, for prizes like air purifiers, electric tea kettles, spindly fruit tree saplings, and a two-burner cooktop paired with oven mitts.

“It’s not just about the climate, but also about violence,” a middle-aged man says in Spanish. He wears a Driscoll’s baseball cap and is accompanied by another man and two women, who say that the most impressive thing they’ve seen at the Climate of Hope Fair is a drone to monitor air quality in the fields in real time for farmworkers. The group says that they typically wait for a certain time interval after spraying before re-entering the fields, but that the drone’s analysis would give them more confidence that it’s really safe for them to return to work tending the strawberries and other produce the region is famous for, post-spray or when wildfire smoke clogs the air.

Climate Fair signage. Photo: Sierra Garcia

The event’s welcome booth, staffed by high schoolers, is adorned with dozens of professional stickers, flyers, and pamphlets, all in both English and Spanish. Many of the booths showcase connections between climate change and other issues — safety for farmworkers in the fields and kids in the streets, health, the high cost of living. Residents and workers in the area have battled through many of California’s extremes, including heat, fire, smoke, and heavy rainfall that breached a levee and flooded the town of Pajaro. But for many, more immediate needs remain top of mind.

“A lot of times, especially here in immigrant communities, we are focused on other things,” says Andrew Valepxia, a local high school senior volunteering for the event. “Like our jobs, and our relationships, and…”. He pauses, and the other volunteer, a young woman who asked not to be quoted by name, chimes in: “It [climate] isn’t a priority. There’s other struggles.”

Valepxia agrees.

In climate advocacy, “it can be sometimes very isolating, feeling like you’re the only voice,” he says. “But once you do take that first step and you see that there is this bigger community, you know that you’re being part of something. And I think that really helps.”

Regeneración plans to organize another event for community feedback in the spring, before presenting the consolidated report by the summer of 2025. The ultimate goal is for funding to go to climate projects that community members need and care about.

Series funded by the CO2 Foundation.

Other Recent Posts

CEQA Reforms: Boon or Brake for Adaptation?

California Environmental Quality Act updates may open up more housing, but some are sounding alarms about bypassed environmental regulations.

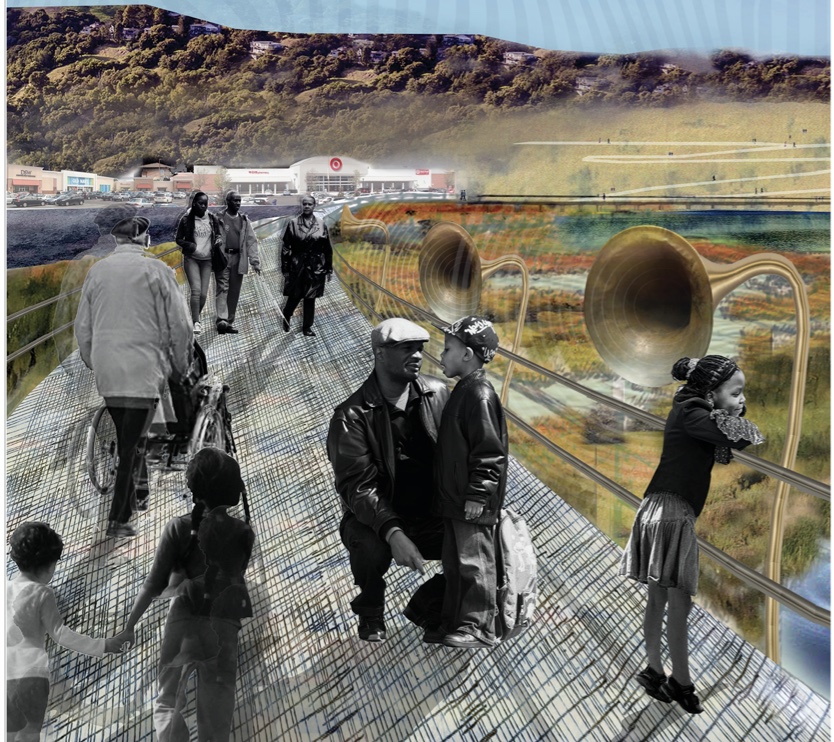

Repurposing Urban Lots & Waterfronts: Ashland Grove Park, Palo Alto Levee, and India Basin

In this edition of our professional column, we look at how groups are reimagining a lot in Ashland Grove and shorelines in San Francisco and Palo Alto.

Backyard Harvests Reduce Waste

A Cupertino Rotary Club program led by Vidula Aiyer harvests backyard fruit and reduces greenhouse gases.

Digging in the Dirt Got Me Into Student Climate Action

A public garden at El Cerrito High School in the East Bay inspired my love of nature and my decision to study environmental science at UCLA.

King Kong Levee: Two Miles Done, Two To Go

Two miles of levee are now in place as part of the project to protect Alviso and parts of San Jose, but construction will last much longer.

Making Shade a Priority in LA: An Interview with Sam Bloch

After witnessing fire disasters in neighboring counties, Marin formed a unique fire prevention authority and taxpayers funded it. Thirty projects and three years later, the county is clearer of undergrowth.

Without Transit Rescue Measure, Bay Area Faces Major Climate Setback

BART, Caltrain, Muni, and AC Transit could face devastating cuts, pushing thousands more cars onto Bay Area roads, unless voters intervene.