Overhauling Insurance for the New Normal

In the era of global warming, an invisible force, as primal in its way as atmospheric chemistry, is coming to bear on human pocketbooks and decisions. “It doesn’t matter if you don’t believe in climate change,” observes Nick VinZant, senior research analyst for an outfit called QuoteWizard. “Your insurance company does.”

California woodland dwellers can attest to that. The dire summers of recent years have made fire policies harder to get. Between 2015 and 2019, the California Department of Insurance reports, almost 350,000 policies in rural areas were canceled. The substitute coverage of last resort, known as the FAIR Plan, is widely panned as inadequate. Regulators seem to face a choice between two bad things: letting people suffer or subsidizing risky behavior by keeping insurance too available and cheap.

This could be a false dichotomy, though, as a new experiment in flood insurance seeks to prove.

The little city of Isleton, on Brannan-Andrus Island in the heart of the Delta, needs better defenses against unruly rivers and rising tides. Its inhabitants also need more, and more affordable, flood insurance. Now local leaders have set their feet on a path that may help Isleton — and many places like it — achieve both these things at once.

Jargon alert. The plan brings together two innovations: community-benefit insurance and something called a Geologic Hazard Abatement District, or GHAD. Community-benefit insurance was devised with poorer parts of the world in mind. In this model, insurance is extended not to a set of individuals but to a local government or other organization, which serves as middleman to a populace — all of which, or most of which, is covered with no need for individual underwriting or contract.

The Geologic Hazard Abatement District, a uniquely Californian critter authorized in 1979, provides a way of organizing against environmental dangers. Most of these districts cover areas afflicted with landslides. Each such district must prepare a Plan of Control and can tax its residents in various ways to execute it.

The threat at Isleton, as in other Delta “legacy communities,” comes not from the hills but from the waters. It has flooded at least five times since its founding in 1874. The levees it depends on are deficient; the cost of a thorough upgrade, daunting. Even a heavy rain can overtax storm drains that lie below sea level. The whole island is classified by FEMA as an A district, meaning that flood insurance is required in order to take out a mortgage. The many residents who do not have mortgages, on the other hand, are seldom insured at all.

Isleton home on stilts, as required for A district homes in search of insurance. Photo: Amber Manfree.

On March 29, five Isleton citizens met for the first time as the board of the Delta Region GHAD, setting not one precedent but three. This is the first such district in a rural area. It is the first one formed to deal with flood danger. And it is the first such district with plans to enter the insurance business.

As its name signals, its backers are betting that its formula will appeal to areas well beyond the narrow limits of the originating town. (GHADs don’t have to be contiguous, and can cross county lines.) The state is watching, too. “The State Department of Insurance is keen on this,” notes Isleton city manager Charles Bergson. “The Department of Conservation is keen.”

This recipe being tested here is the creation of several chefs. One is a former flood bureaucrat named Kathleen Schaefer. As regional engineer for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), she understood the traditional system as well as anyone, and didn’t like it much. She found its procedures cumbersome, its attitudes often hidebound. In charge of new and more accurate flood-zone mapping, she saw the spreading distress as more and more acres were shifted to the dreaded map category A. “We marched through,” she says, “like Sherman to the sea.”

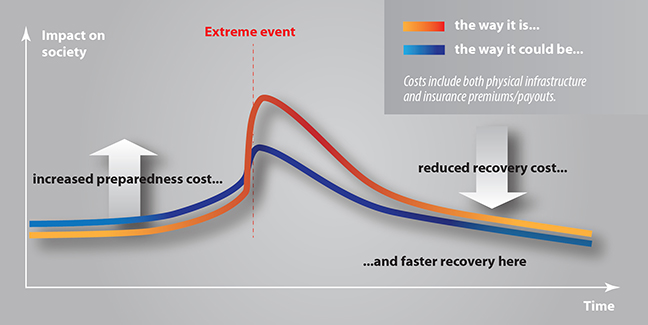

Redrawn for KDT. Original source: WEF 2011.

One thing Schaefer realized at FEMA is that flood insurance premiums in California are actually too high. While the National Flood Insurance Program as a whole is deeply in the red, that’s essentially because of eastern hurricanes. Flood damage in this state is chronic but rarely catastrophic. In fact, Californians pay much more in premiums than they collect in benefits. In addition, premiums paid to the feds help support the agency, a “load” that doubles the core insurance cost. (All insurers have such charges, but not on anything like the FEMA scale.)

Out of government and a PhD candidate at UC Davis, Schaefer began a search for a better way. It involves some high-powered partners. For five years she has conferenced weekly with colleagues from the insurance firm Epic Brokers, the engineering firm ENGEO, and later the global engineering company Munich RE.

That addition was significant. Until recently, it was just about illegal for insurers other than FEMA to cover flood risk. This has changed. Certain specialized “RE” companies, formed to insure insurers themselves against extraordinary losses, have ventured into the general insurance field. Much more sophisticated risk analysis has calmed underwriters’ nerves. And policies now can be “securitized,” lumped into bonds of a sort that attract investors — people who accept the risk of occasional large losses as the price of many profitable years.

At Isleton, many details remain to be set. “We’re starting it slow,” Bergson says. The new district will have to support itself, and that means charges of some sort. If plans work out, everyone will be insured at one of three levels: a basic plan designed to provide ready cash in an emergency; a moderate plan sized and priced to reflect typical California losses; and a “concierge” plan more resembling traditional insurance. Fees attached to policies, and perhaps property taxes as well, will help support the GHAD. Under California’s Proposition 218, the Right to Vote on Taxes Act, not much can happen without an election. The new board has just begun to feel its way.

Isleton’s historic downtown sits well below sea level already. Photo: Amber Manfree.

For the district to fulfill its mission, it must, of course, live up to its name and primary purpose: it must accelerate the solutions to Isleton’s flooding problems. A long list of improvements is under study. Near the top is construction of an elevated “flood fight” berm and road to help in the next emergency. By bringing some of its own money to the work, the district will have a better chance of snagging funds from the state and the feds. Its insurer, too, might kick in, choosing to invest in prevention in hopes of spending less on cure.

Insurance is a complicated subject, and a rather abstract one. It is always tempting to talk about physical works instead. Schaefer urges us to think of insurance as another kind of infrastructure. “A key part of resilience,” she says, “is having money after the event.”

Schaefer and two more colleagues, the eminent wetlands scientist Stuart Siegel and architect and developer Jeffrey Rhoads, have been working quietly with another at-risk community: the Canal neighborhood of San Rafael. Here again an underserved population is physically and financially at risk. Here too, a Geological Hazard Abatement District might be the tool to address both problems at once. But that is a story for another issue of KneeDeep Times.