Optimizing the Health Benefits of Urban Greens

The same features in urban parks that support biodiversity can also benefit human health. Even biodiversity itself may help us — and the San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI) wants to see more of it. To that end, the nonprofit released an innovative report in September called Ecology for Health. It’s a practical guide for planners and designers to aid both biodiversity and human health in urban settings.

Research into the link between nature and human health goes back decades. But scientists continue to learn more about which aspects of parks and other green spaces in cities — such as recreational amenities, shade, views, or plants and animal life — are most associated with different mental and physical health outcomes in humans, says SFEI environmental analyst Jennifer Symonds. One of seven co-authors of the report, Symonds also led an exhaustive review of the existing literature.

A conclusion that’s become increasingly clear (and that inspired SFEI to produce the guide in the first place, Symonds says) is that plant, animal, fungal, and human life can be intertwined to a fascinating extent, even in urban settings.

Two recent studies suggest that greater bird diversity is tied to better human well-being. And a 2007 study showed a positive association between overall plant diversity and human psychological well-being: the more of one, the more of the other. Plant species richness also has been linked to human microbiota biodiversity, Symonds says. “That is linked to improved human health, including reduced skin disease,” among other benefits.

Research has also shown that urban forests can (take a deep breath) improve mood, mental health, immune function, and BMI, and lower the prevalence of lung cancer, asthma, heat-related mortality, and preterm birth. Native flowering plants, meanwhile, may help reduce allergen sensitivity.

All of these can be deliberately designed into city parks and open spaces for maximum benefit, and that’s the main message behind SFEI’s new report.

Some features, however, might have to go. Artificial lighting is known to affect wildlife communication, orientation, reproduction timing, predation, habitat selection, and more. In humans, it’s “linked to increased breast and prostate cancer risk, increased cortisol, increased vector borne disease risk, and disruptions to circadian rhythm and melatonin production,” a chapter in the report on lighting reads. To reduce these impacts, the authors recommend limiting outdoor light intensity and “trespass,” also called light pollution, and avoiding blue-white light.

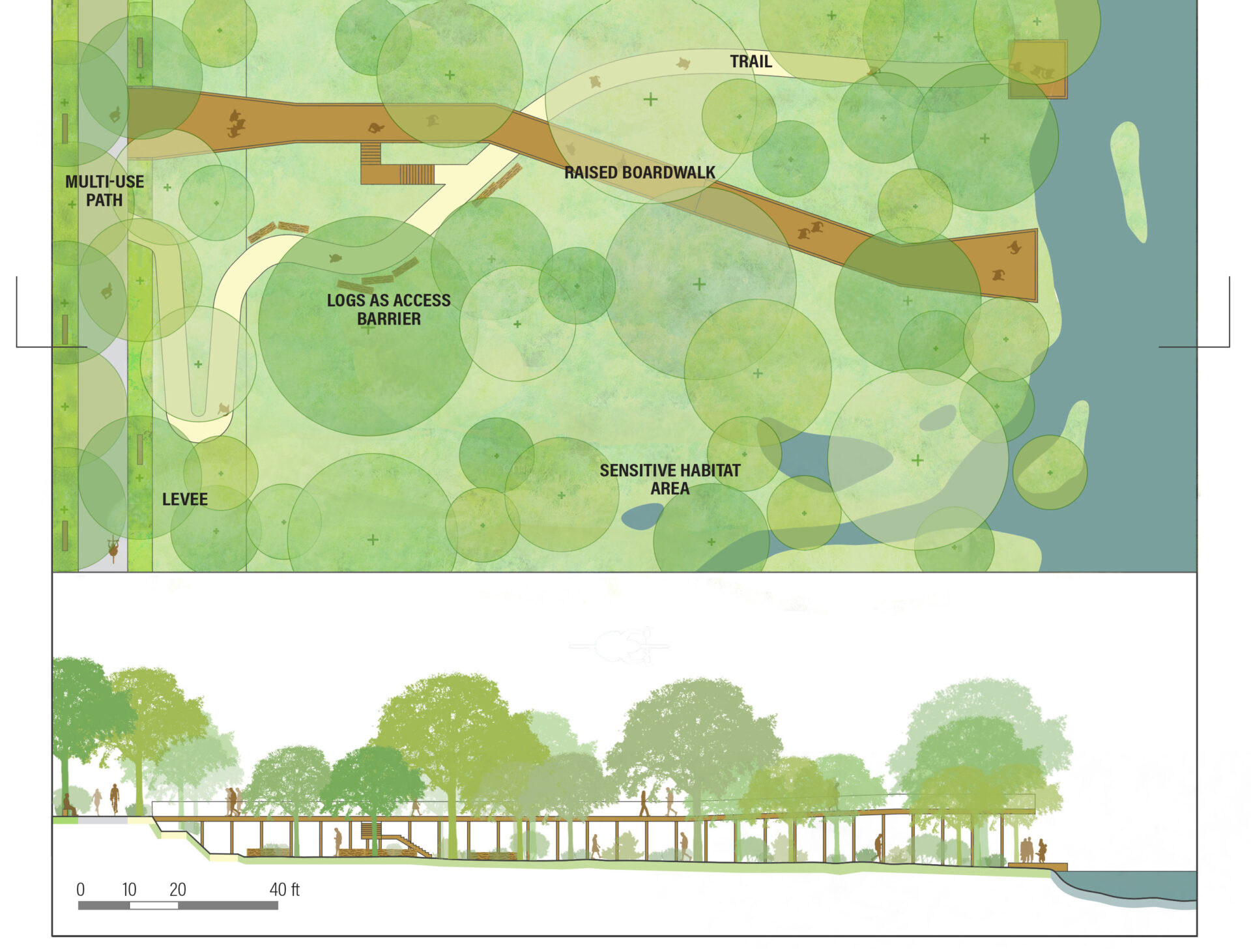

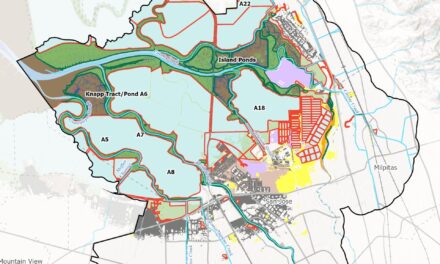

Other chapters in the report offer practical guidance on water features, grass alternatives, garden spaces, habitat complexity, and public access. And alongside direct impacts on health, the authors also explore co-benefits for things like shade and cooling, climate mitigation and adaptation, and flood and stormwater management — a suite of benefits sometimes referred to as “ecosystem services.”

Of course there are challenges. In some cases, the needs of people and nature conflict. Recreational access can disturb wildlife. Habitat complexity may reduce human access or perceived safety. And green spaces may take land away from other valuable uses like affordable housing.

The guide tackles these, too, with practical insights throughout. “We are excited to present this design guidance showing synergies and also addressing the tradeoffs between biodiversity and human health in urban spaces,” says co-author Karen Verpeet, SFEI’s Resilient Landscapes Program managing director.

SFEI’s goal now is to get eyes on Ecology For Health. In September, the organization gathered more than 50 local planners, designers, landscape architects, and other experts to review and discuss the report. “We’ve already gotten some really good feedback,” Symonds says.

Other Recent Posts

ESA

ESA is an environmental engineering firm that does restoration and resilience projects.

Gleaning in the Giving Season

The practice of collecting food left behind in fields after the harvest is good for the environment and gives more people access to produce.

New Study Teases Out Seawall Impacts

New models suggest that sea walls and levees provide protection against flooding and rising seas with little effect on surrounding areas.

Oakland High Schoolers Sample Local Kayaking

The Oakland Goes Outdoors program gives low-income students a chance to kayak, hike, and camp.

Growing Better Tomatoes with Less Water

UC Santa Cruz researchers find the highly-desired ‘Early Girl’ variety yields more tomatoes under dry-farmed conditions.

Santa Clara Helps Homeless Out of Harm’s Way

A year after adopting a controversial camping ban, Valley Water is trying to move unsheltered people out of the cold and rain.

The Race Against Runoff

San Francisco redesigns drains, parks, permeable pavements and buildings to keep stormwater out of the Bay and build flood resilience.

Learning the Art of Burning to Prevent Wildfire

In Santa Rosa’s Pepperwood Preserve, volunteers are learning how controlled fires can clear out natural wildfire fuel before it can spark.

Martinez Residents Want More Than Apologies — They Want Protection

After a 2022 release of toxic dust and a February 2025 fire, people in the northeast Bay town are tired of waiting for safety improvements.

Weaving Fire Protection Out Of What’s Already There

A new Greenbelt Alliance report shows how existing vineyards, grasslands, and managed forests can slow wildfire and save vulnerable homes.