On Napa’s Milton Road, No Resident Is an Island

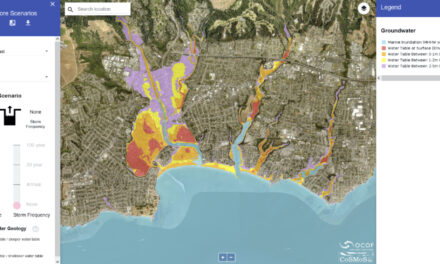

In Napa County, a community of 150 homes sits behind a 100-year-old levee. In a hundred more years, the homes it was never built to protect will be underwater. Unless, somehow, they can agree to pay the cost of resilience.

A 6.0 magnitude earthquake struck southern Napa County on August 24, 2014. The South Napa earthquake — the strongest to hit the Bay Area since Loma Prieta in 1989 — caused 200 injuries and one death. It battered many historic buildings in the city of Napa. And in the southernmost reaches of southern Napa, very near the epicenter, it damaged Darren Milman’s levee. He wasted no time in fixing it.

“I built it higher at that point,” he explains, tossing a ball for Joey, his shepherd. Joey loves it here in the trails of the Napa-Sonoma Marshes Wildlife Area. So does Milman, who lives on Milton Road, which dead-ends at the park. But it’s not always the easiest place to live. The quick levee fix that he made following the quake was a way to keep his home safe, sure. But it also kept him in his neighbors’ good graces. “You know, I always had … I don’t know what you call it, like, levee shame,” he says, chuckling.

When he bought his home on Milton Road in 2010, Milman also bought the section of the levee that separates it from the Napa River. That’s how it is for all of the more than 150 homes along the road on Edgerly Island and Ingersoll Tract. Residents here all agree: maintaining the levee behind each home is that homeowner’s responsibility. What they cannot agree on is how to adequately protect the community from a slow-moving disaster that, unlike the next earthquake, is arriving on a fairly predictable timeline: sea level rise.

Some homes in the Milton Road community are trying to keep up with the changes, while others may not have the resources. Photo: Mary Catherine O’Connor

In 2018, environmental consulting firm ESA published the 180-page Edgerly Island and Ingersoll Tract Flood Management Plan and Adaptation Study. It laid out three recommendations for how residents here could prepare for what will likely be 24 inches of higher water by 2050. For such a sleepy-sounding report, the study caused a great deal of drama and division in this community. ”We had these meetings, you know, people were just getting, not violent … but it wasn’t pretty,” says another Milton Road resident, Richard Newman.

The ESA report didn’t mince words when it comes to the hazards residents face, warning that even a single breach on just one Edgerly Island parcel could introduce several feet of water across the island during high tides and floods. The levee, built in the early 1900s, sits atop soils now compressed under the weight of buildings and the road. Combine reduced levee height with sea level rise, and flooding is likely to become a daily, not decadal, event, the report warned.

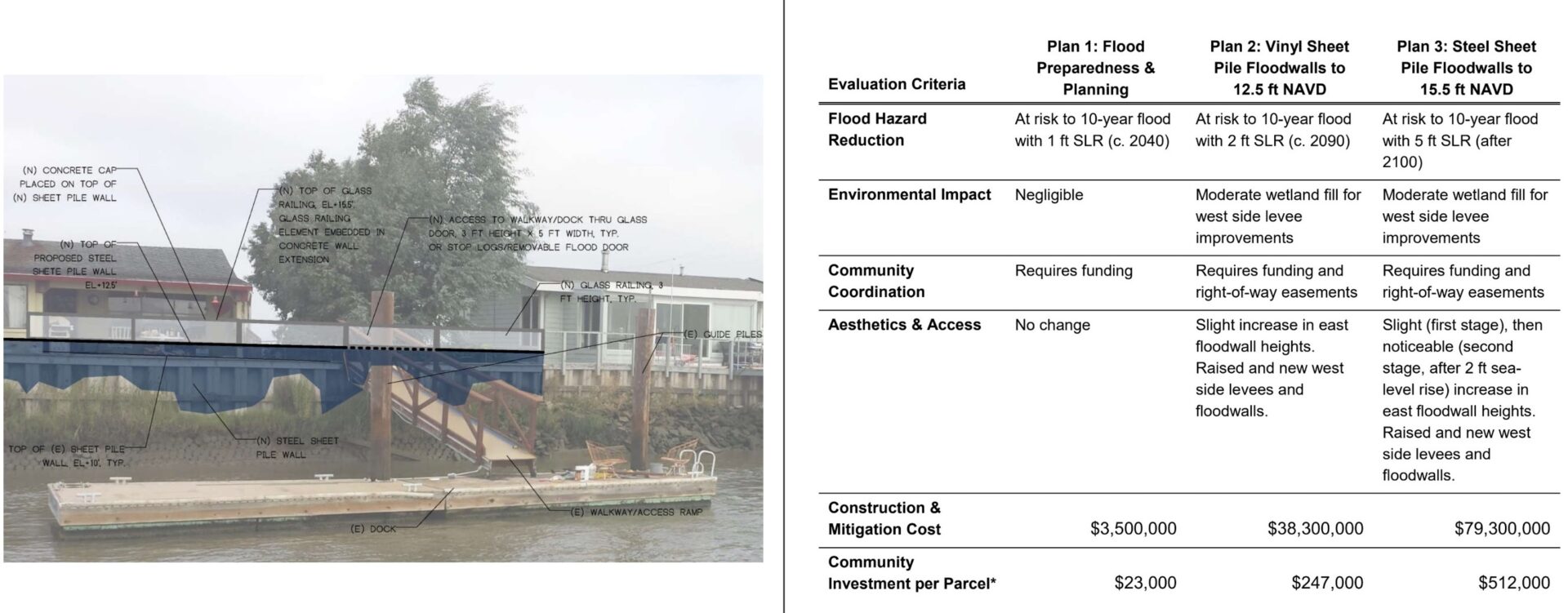

The report laid out three proposals that come with escalating costs, but also longevity. They range from raising a levee repair fund and hiring a manager to oversee improvements, to committing to building substantial floodwalls and raising some buildings. The very rough cost estimates range from $3.5 to $8 million, or $23 thousand to $500 thousand per parcel share of the total investment.

Comparison of flood management plans and costs per parcel share of the total community investment in the plan (rather than per parcel owner). Table & Rendering: ESA

After meeting for the better part of two years, the community could not agree on an approach. “I guess … this is the way it is for now. There’s been no community-wide decision made to do anything,” says Darren Millman. “It’s a very expensive proposition to bring the levee up to the level where it will need to be for the future.”

But to Newman, a major flood — which hasn’t happened here since the 1980s — could doom the community. ”If the levee failed bad enough that the street flooded, it would take our sewer system out and that would red tag the neighborhood. And it could actually, at some point, condemn the whole area.”

A Reclamation District That Can’t Claim Authority

The levee around Edgerly Island was built decades before the island was subdivided into private lots in 1945. Initially, the structures here were mostly weekend fishing cabins. (Newman’s father-in-law built one in the 1960s, which he and his wife now live in.) Flooding occurred every five years or so as cabins turned into year-round homes. Floods in 1967 and 1973 were caused, not by storms, but just by high tides. Napa County was responsible for enforcing levee maintenance, and wanted to hand control to a local agency. So in 1974 it created the Edgerly Island Reclamation District, which was to hold the authority over levee maintenance.

Unfortunately the district never did its job. That was among the findings of a Napa County Grand Jury report published in 2016. The grand jury found that the reclamation district — which had been renamed the Napa River Reclamation District — was never given legal authority needed to maintain the levee, nor had it gotten the easements or raised the money necessary to do the work. The report blamed the failures on the reclamation district and a list of local agencies. It also highlighted concerns that the costs of a major flood on Edgerly Island would fall on taxpayers.

Water level and levee near Milton Road. Photo: Mary Catherine O’Connor

In the wake of the report, the NRRD and Napa County Flood Control & Water Conservation District co-funded ESA’s research. Clearly, relying on peer pressure among neighbors to keep the levee maintained just wasn’t going to cut it.

Today, the reclamation district is run by five trustees, community members who do the work voluntarily. In 2018, long-time local Jay Gardner was the board president and tried to guide the community toward a decision following the report. According to Newman, also a board member, the vitriol and disagreement were so intense that Gardner quit. “He was just beaten down,” says Newman. “And his intentions were nothing but stellar.” Gardner declined to speak to KneeDeep Times. And the three others did not respond to interview requests.

Love It or List It

Erica Neubauer, Gardner’s daughter, grew up on Milton Road. After living in a number of U.S. cities and abroad, she has returned to raise her kids here, a place she describes as a close-knit community despite the division over the levee. When I arrive, she is collecting bike helmets and toys from the driveway.

“I don’t know what is going to happen,” she says, referring to the levee debate. “A lot of people just want to see things stay the same.”

Neubauer acknowledges and worries about sea level rise, and says she’s in favor of building a floodwall.

“I personally would love to stay here the rest of my life,” she says. And it’s obvious why, as we walk to the back of her home and the Napa River comes into view. It’s gorgeous. The calm water reflects big puffy clouds and sections of blue sky. But I can also see why living here is fraught. The past few days have been very rainy, and the tide is rising. The water laps at her back stairs. Neubauer says her neighbors likely took on some water.

Erica Neubauer in front of her raised house. Photo: Mary Catherine O’Connor

Her own house is much taller, and it was just remodeled with rising water in mind. The first floor is used for garage and storage — no living space — and built into the back and front of the foundation are flaps that will open, should water rush in from the river, and allow floodwater to flow into a drainage ditch.

“That’s smart,” says Kris May, CEO of climate adaptation firm Pathways Climate Institute, during a later phone interview. “It really reduces damage to your structure in a flood.”

But as she scans the renderings of the two different floodwall proposals in the ESA report, May says that aside from the obvious hurdle of funding, homeowners are likely also concerned about aesthetics. In some cases, they’d need to trade that river view for gazing upon … infrastructure.

View of community over docks and current levee from Napa River. Photo: Karl Nielsen

Whatever the size and strength of any new flood protection, the hardest part of all will be getting the community to drive toward a decision. “Engineering is hard, but not as hard as the social part,” says May.

Newman sees parallels between the ongoing debate over how to protect his community and a similar one playing out in Pacifica, where coastal erosion has already displaced some residents. (Other parallels can be found in Marin’s struggle to get 100+ easements for flood protection in Santa Venetia.)

On Milton Road, Newman says the mix of residents presents a huge challenge and likely stokes the disagreement. Some older homes are clearly in need of improvements, with living spaces right up to the levee wall. Other homes, like Neubauer’s, have been rebuilt or heavily rehabbed with sea level rise in mind. The variations from one home to the next are often stark, and Newman says that over time, as older residents move and are replaced by wealthy newcomers who could afford to pay for improvements, the community will change and the buildings and sections of levee will improve.

Milton Road’s proximity to local marshes offers both a flood buffer and recreational opportunities (Joey awaits a ball toss from a levee-top trail). Photos: Mary Catherine O’Connor and Darren Milman.

But it may only take one section of failed levee to cause widespread destruction on the Edgerly Island and Ingersoll tract.

Even though he knows the waters are rising and something has to change, at 71, Newman is hoping that he and his wife can remain here for the rest of their days. I ask if they’ll pass the property onto their kids, as his father-in-law passed it on.

“Oh yeah,” he says. “But I know when my kids get it, they’re just going to sell it.”