New Maps Reveal Bay Area Flood Threat From Below

As Bay Area residents kayaked through flooded streets and bailed out buildings during California’s recent storms, they faced not only bursting creeks and pouring rain but also rising groundwater.

“During a big storm, there’s just water everywhere,” says Ellen Plane, an environmental scientist at the San Francisco Estuary Institute. “We have it from basically all directions.”

With climate change, water from below is poised to get worse. As sea levels rise, so will Bay Area water tables. A new mapping project aims to give planners the data they need to act.

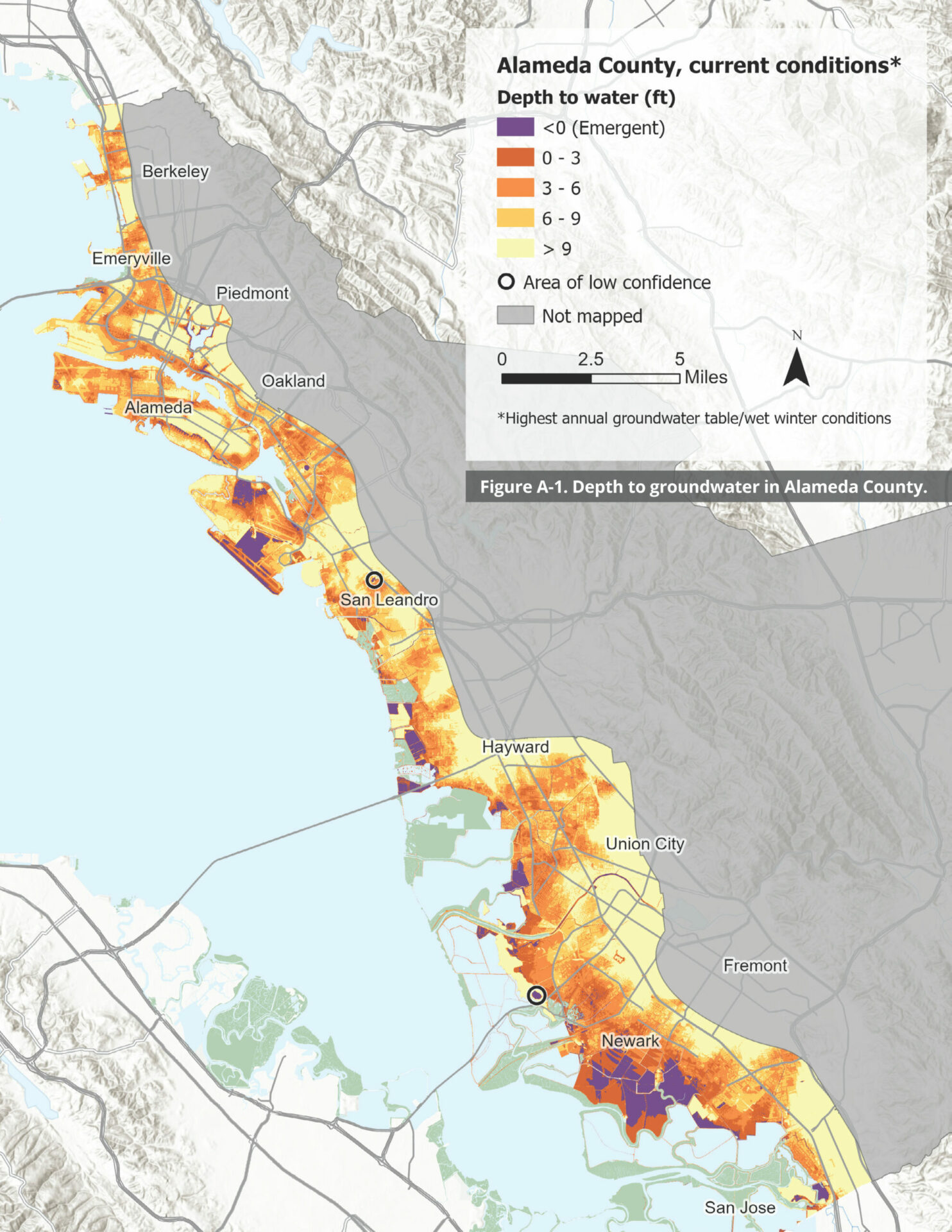

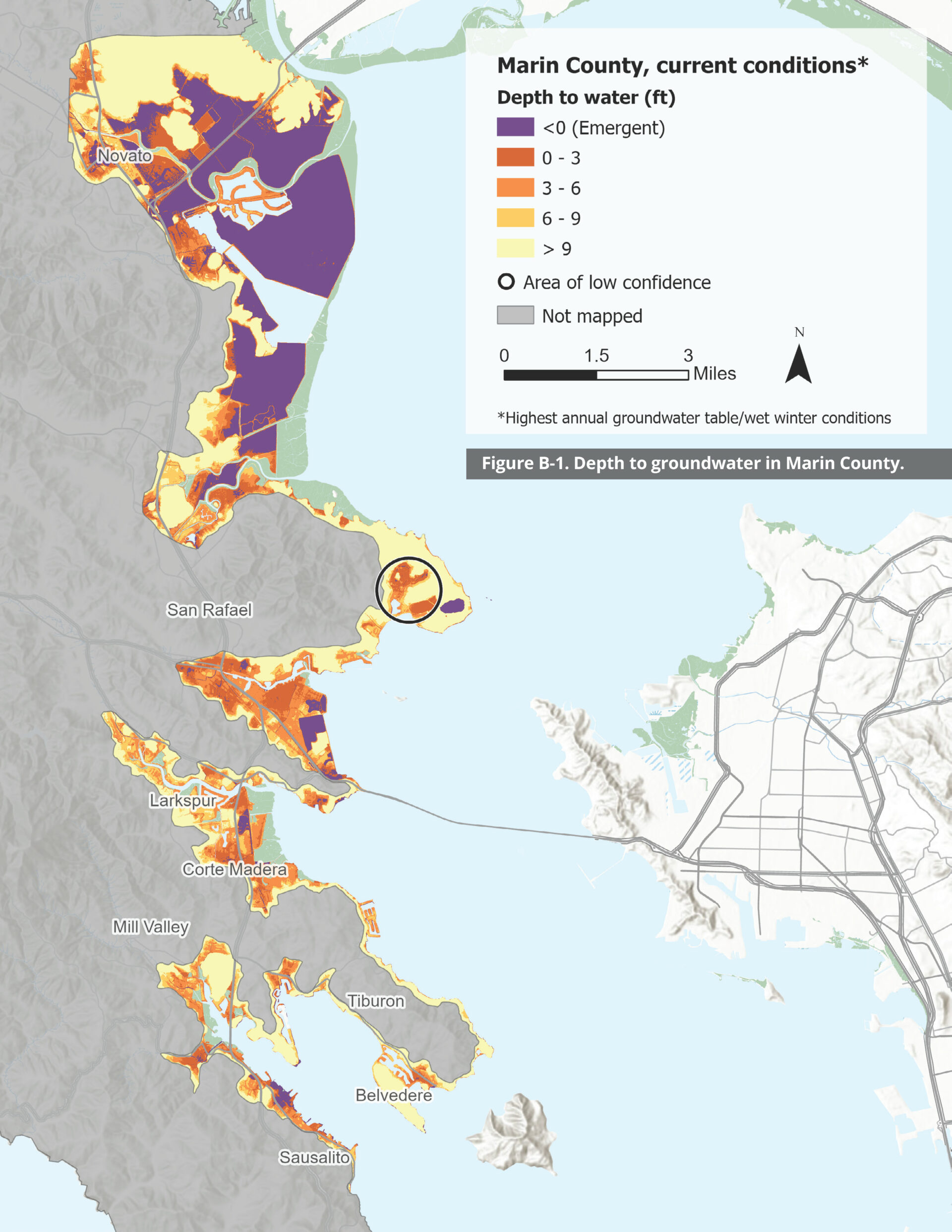

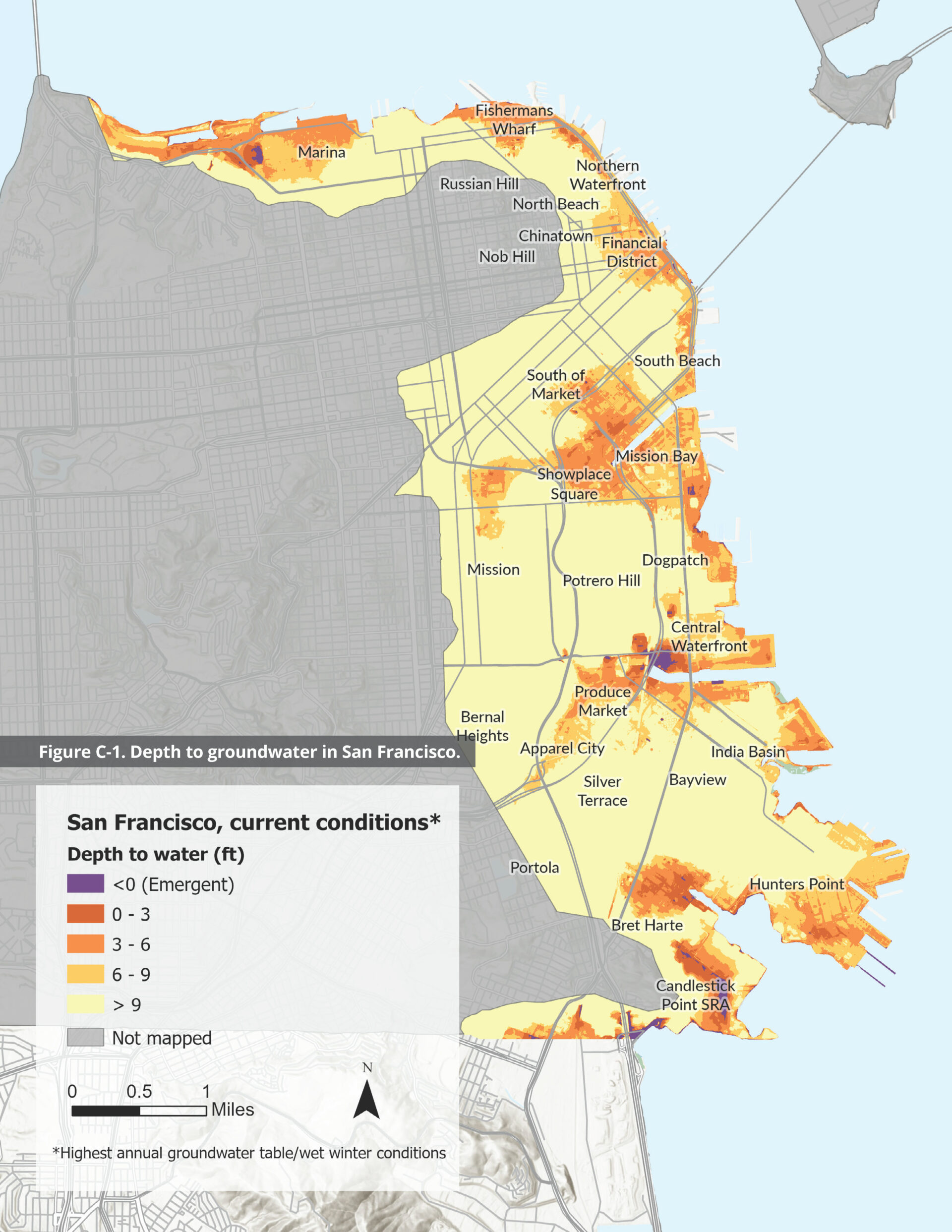

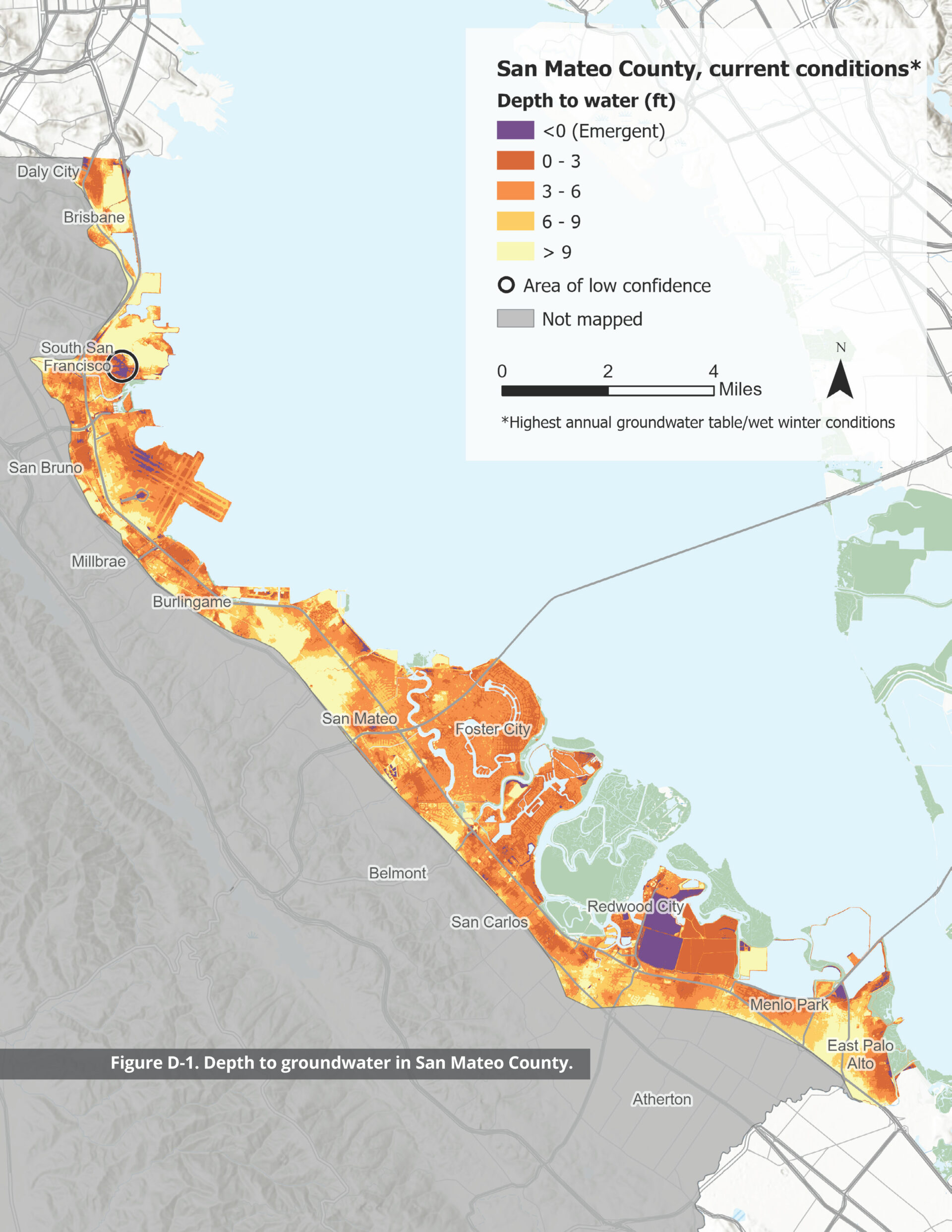

The Shallow Groundwater Response to Sea-Level Rise report, released this week from Pathways Climate Institute and San Francisco Estuary Institute, provides current groundwater maps and comprehensive projections for Alameda, Marin, San Francisco, and San Mateo counties. It models scenarios from one foot to nine feet of sea level rise.

While rising seas are often associated with visibly shrinking beaches and eroding coastlines, sea level rise also means salt water quietly advancing inland. This underground seawater forms a “wedge” below lighter freshwaters, raising baseline groundwater levels.

Due to these groundwater changes, many existing climate adaptation plans have not fully reckoned with, “how far inland the impacts of sea level rise would really reach,” Plane says. Higher water tables will make floods worse in areas that already flood frequently. They will also cause new flood risks in places that historically have stayed high and dry. Soggier ground also brings new risks during earthquakes.

Today, “emergent groundwater,” or flooding from below, mostly appears close to the edges of creeks and wetlands. At nine feet of sea level rise, the new maps show, most land west of Interstate 880 in the East Bay and east of Interstate 101 on the Peninsula is likely to be inundated in wet winters. Much of that land, Plane points out, could be underwater anyway from the more direct impacts of sea level rise. But if levees are built to hold back the waves, planners will need additional solutions for groundwater coming up from below.

There are also less visible risks. “Between zero and six feet is where a lot of our buried infrastructure is located,” Plane says. Bay Area governments will need to plan ahead to avoid damage like cracked foundations or leaking and corroded pipes: just one foot of sea level rise would raise groundwater to this level for much of the land that was mapped.

County maps of groundwater flood threat. Source: SFEI/Pathways.

Governments will also need to address low-lying hazards, from the radioactive waste at the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard Superfund sites to landfills and other contamination sites. All pose risks to already vulnerable communities nearby.

“One of the biggest concerns about rising groundwater is that it can re-mobilize contaminants and send them in new directions,” says Plane, adding that many contaminated sites are sealed from above but not from below.

The safest approaches for some of these sites, Plane says, likely come with astronomical price tags. Still, she hopes that planners will use this data, “to figure out what needs to be done to keep communities safe.”

Some strategies for dealing with groundwater impacts already exist, and a number of local governments collaborated on the report. “I don’t want this to be a panic-inducing moment,” Plane says. Used well, she believes the report will give local governments the data they need to allocate adequate funding and to plan ahead.

MORE

- Explore maps showing current groundwater levels around the Bay Area.

- See maps of how groundwater levels are projected to rise.

- Read the full Shallow Groundwater Response to Sea-Level Rise report.