Photo: United Way Mumbai

Mumbai’s Microforests Model Cooling for California

As the Bay Area faces hotter temperatures, urban planners may look to tree-rich cities like Mumbai, India as a model of climate resilience. Despite being highly urbanized, Mumbai has successfully implemented the Miyawaki method for creating forests, planting over 78 micro-forests since 2020. These dense, fast-growing forests help combat climate change by reducing urban heat, enhancing biodiversity and improving air quality. While Miyawaki forests show promise, their effectiveness in the Bay Area remains to be fully seen.

FULL READ

Mumbai’s Microforests Model Cooling for California

In just 30 years, the majority of Bay Area counties are projected to witness more than twice as many days over 100 degrees as they do today. Despite the rising temperatures, green spaces continue to be replaced with concrete. Trees and vegetation reduce temperatures, so it is no surprise that a myriad of tree-planting programs are now taking place throughout the Bay Area to offset urbanization. One of these initiatives — a push to create microforests using a Japanese method known as Miyawaki — is just starting to gain traction in the Bay Area, with a handful planted to date. Meanwhile, the city of Mumbai, India has embraced the Miyawaki Forest full on. Since January 2020, Mumbai has built 78 microforests, planting over 500,000 trees.

Now one of the most tree-rich cities in the world, Mumbai is also the world’s second most densely populated — and one of the most vulnerable to the ravages of climate change. To increase its green cover and improve its resilience to our warming world, the city’s civic administration identified more than 1,100 plots of land to build Miyawaki forests. These land parcels are now being “developed into Mumbai’s green lungs,” says Jeetendra Pardeshi, superintendent of gardens and tree officer, who has been leading the Mumbai civic authority’s green infrastructure development.

“As temperatures rise, Miyawaki forests are a sustainable solution to combating climate change. Last year, we also mandated all property developers to reserve five percent of their land for Miyawaki plantations if the area exceeds 10,000 square meters,” Pardeshi says.

Mumbai’s Miyawaki project has been lauded globally, and for the past three consecutive years, the Food and Agriculture Organization, a specialized agency of the United Nations, has awarded Mumbai the Tree City of the World award, recognizing its “commitment to growing and maintaining urban trees and greenery in building healthy, resilient and happy cities.”

Miyawaki forests offer a wide range of benefits, says Myron Mendes, national facilitator of the Indian Network on Ethics and Climate Change. These forests grow rapidly, providing a quick green cover that is crucial for cities grappling with the effects of climate change. They help reduce the urban heat island effect, where densely built environments trap heat, making cities warmer than rural areas. They mimic natural forests, supporting a wide variety of plant and animal life, and fostering biodiverse ecosystems that are often missing from urban landscapes. They enhance the overall environmental health of the city, and they also absorb pollutants from the air, improving air quality.

Photo courtesy: Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation

“Miyawaki forests represent a practical and impactful way to make our cities more sustainable and livable,” Mendes says. “By introducing these green patches throughout the city, we can cool down our urban areas, making them more resilient to rising temperatures.”

Hence, it is no surprise that the Miyawaki method is rapidly gaining popularity in countries around the world, including France, Jordan, Malaysia and Brazil.

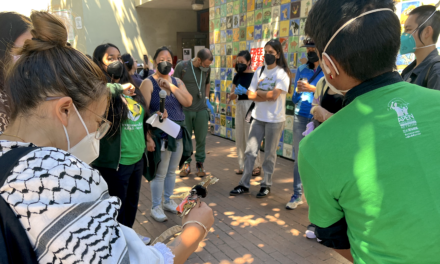

The Miyawaki Method

In 2022, United Way Mumbai, an Indian nonprofit organization, removed 50 cubic metric tons of waste from a landfill site spread over 125,000 square feet in the northern Indian city of Ghaziabad. Using the Miyawaki method, they planted nearly 35,000 saplings of 40 tree species, transforming the site from a landfill to a green zone within the city. The project created volunteer opportunities for students and citizens, and according to a recent biodiversity study conducted by the organization, more than 20 new species of birds, insects, and herbs have been observed at the site.

“We have built 17 such forests across seven Indian cities since 2018, planting nearly 120,000 trees and greening over 400,000 square feet of urban land across the country,” says Manashree Mantri, a manager with the Community Impact initiative of United Way Mumbai, which has been spearheading these urban afforestation projects (the process of planting trees where forests never existed before.).

Landfill project. Photo: United Way Mumbai

Pioneered by the master Japanese botanist, Akira Miyawaki, in the 1980s, the Miyawaki method is known as one of the most effective ways of urban afforestation. The approach involves planting a variety of native species in close proximity to each other. The methods work well for cities, where land is limited, and Miyawaki forests are known to grow 10 times faster, are 100 times more biodiverse, and have 30 times more green surface area.

Ajay Govale, vice president of United Way Mumbai’s Community Impact initiative, says that their urban afforestation projects are usually funded by corporations as part of the mandatory Corporate Social Responsibility compliance in India. When choosing a site for a Miyawaki forest, the organization’s first criteria is that the plot should not be on private land, but should be accessible to and benefit the local community. Once a site is identified and approved by horticulturists, the NGO seeks a commitment from the landowner, usually a government entity, to retain the forest for at least a decade. The organization then starts preparing the soil for Miyawaki plantation, a resource-intensive effort where the ground is dug up to three meters, and different types of organic material are added to the soil.

The soil has to be rich in nutrients, as this allows the forest to continue to grow without the need for additional manure, says Ankur Joshi, a taxonomist and assistant manager with the organization. “Because so many species grow in a small patch of land, the saplings need a lot of nutrients from the soil,” he explains.

Birds flock to Mumbai’s microforests. Photo courtesy: Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation

Over the next two years, the organization ensures that the forest is adequately maintained, which primarily involves removing weeds and invasive species that are attracted to them because of the nutrients added to the soil. “After about two years, once our trees are established, we leave the forest to grow on its own, following the natural law of survival of the fittest. The species compete with each other for sunlight, which helps them grow 10 times faster,” Joshi says.

According to Mukesh Dev, a senior manager with United Way Mumbai and a watershed, soil and water conservation engineer, Miyawaki forests require a lot of water, and hence, to reduce water waste, the organization has come up with methods like drip irrigation, which involves placing tubes alongside the plants. The tubes slowly drip water into the soil, preventing wastage.

“So instead of using tankers to flood the area with water, we convince our donors to also pay for drip irrigation set ups at the site,” Dev says, adding that the organization, based on the local climate, water availability and land topography, also tries to plant drought-resilient species, which require less water.

Local Applications?

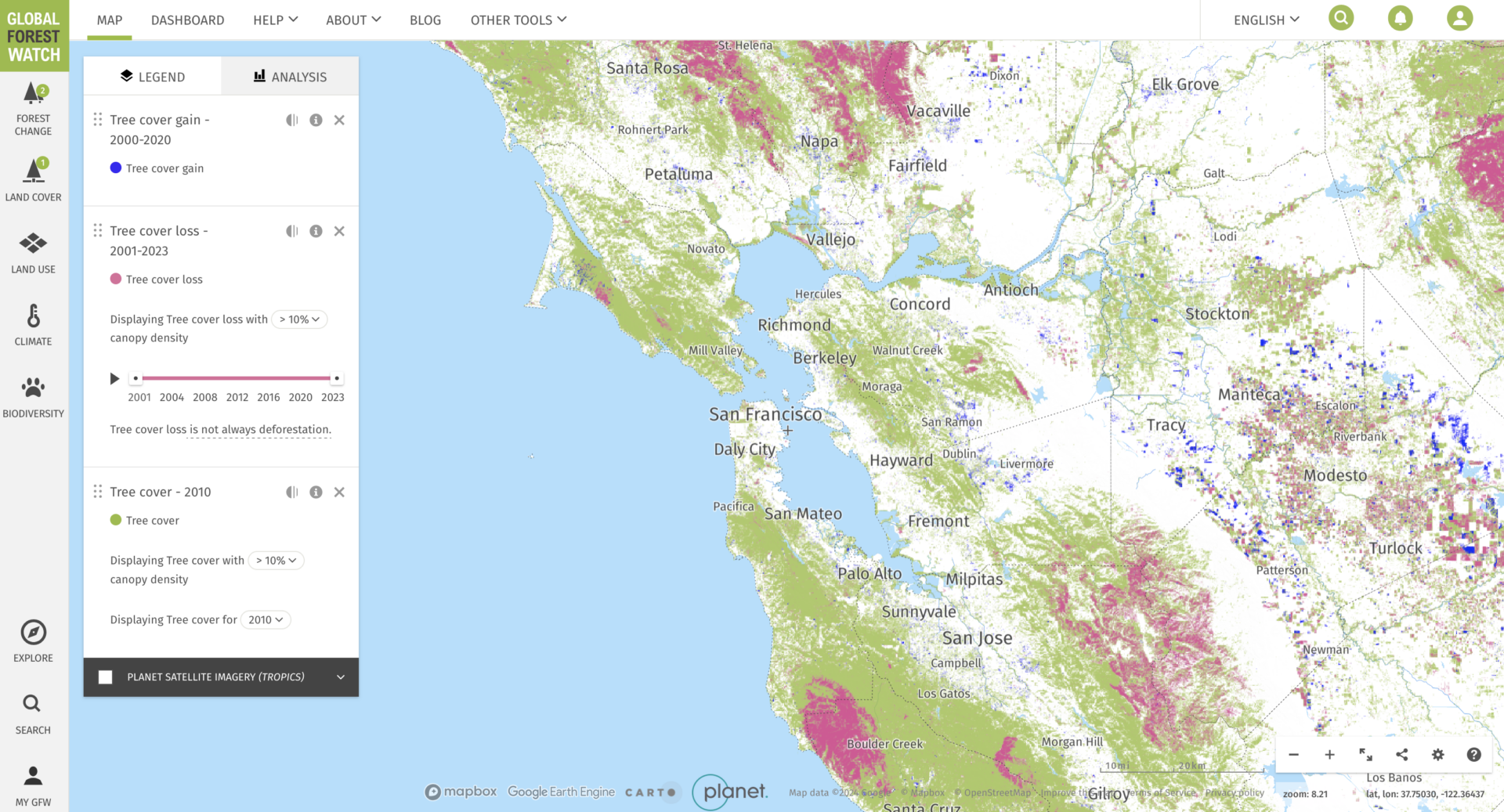

A quick look at satellite imagery for a sampling of Bay Area counties suggests that between 2001 and 2021, Napa, Alameda, and Santa Clara have all seen a loss in forested area. Sonoma County, conversely, has seen an increase.

Source: Global Forest Watch

According to an earlier study by the University of California, Davis, between 1984 and 2002, urbanized areas in the San Francisco Bay Area witnessed a 73% expansion, while the tree cover increased by a mere 10%. The study notes that the Bay Area has 300 square miles of existing urban forest, which already offers environmental and other benefits worth $5.2 billion. For example, these trees moderate the temperature, absorbing pollutants given off at power plants, and reducing energy costs by more than $330 million annually. The urban forest also helps protect the Bay by intercepting and storing rainwater, reducing runoff, and slowing erosion (hydrology services worth $102 million every year). The region’s urban forests also sequester carbon, reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide levels by almost 600,000 tons a year, valued at nearly $4 million.

“Many benefits attributed to urban trees are difficult to translate into economic terms, such as beautification, privacy, shade that increases human comfort, wildlife habitat, sense of place, and well-being,” the study notes. “By investing in trees and tree care, residents of the nine counties of the San Francisco Bay area can enjoy the many ecosystem services that the urban forest provides.”

Urban street trees getting a haircut along Versailles Avenue in Alameda. Photo: Maurice Ramirez

Students and community members of the Berkeley Unified School District have already planted four urban forests using the Miyawaki method in schools across Berkeley. Such forests are also cropping up elsewhere in the US, including Florida, Los Angeles and Cambridge. In July, the city of Berkeley invited proposals from qualified firms or individuals for “the design and installation of two Miyawaki forests on city-maintained property.”

Further, in mid-August, Tyrone Jue, San Francisco’s chief climate and sustainability executive, convened a meeting through the World Economic Forum Commission on Nature Positive Cities. According to an email, he discussed exploring the Miyawaki method and signed on to a 1 trillion tree pledge, aimed at growing the city’s urban biodiversity and canopy and ensuring a healthier and more inclusive future for San Franciscans.

“Only about a third of the world’s most populous cities have developed a strategy focused on nature and biodiversity preservation,” he wrote.

A walk through the greenery and beauty of a microforest.

While the Miyawaki method offers numerous benefits, especially in urban areas, Mendes of the Indian Network on Ethics and Climate Change feels that as our world warms and cities face increasing climate threats, governments must adopt a multi-faceted approach to building urban resilience. An example is creating green corridors that connect parks and natural spaces throughout cities, enhancing biodiversity, reducing heat, and improving air quality on a larger scale. Similarly, sustainable public transportation, climate-resilient architecture and energy-efficient buildings can significantly reduce a city’s carbon footprint, making it more adaptable to rising temperatures.

“While the Miyawaki method is a valuable tool in our urban resilience toolkit, it should be complemented with broader strategies that address the diverse challenges posed by climate change,” Mendes says. “By adopting an integrated approach that includes green infrastructure, sustainable water management, and climate-resilient urban design, we can better equip our cities to withstand and thrive in the face of a warming world.”