Mapping Those Most At Risk

When planning for climate disaster, many federal agencies assess risk on the scale of cities and counties. But in reality, neighborhoods within a city are impacted very differently from one another. A flood that hits Bayview-Hunters Point in San Francisco would pummel a dense, 96% minority community with a poverty rate nearly three times as high as the county average. That same flood in the Marina District would encounter a spread-out, predominantly white, and highly educated population with an average salary nearly ten times greater than Bayview-Hunters Point’s — making the area far more able to withstand the flood and bounce back.

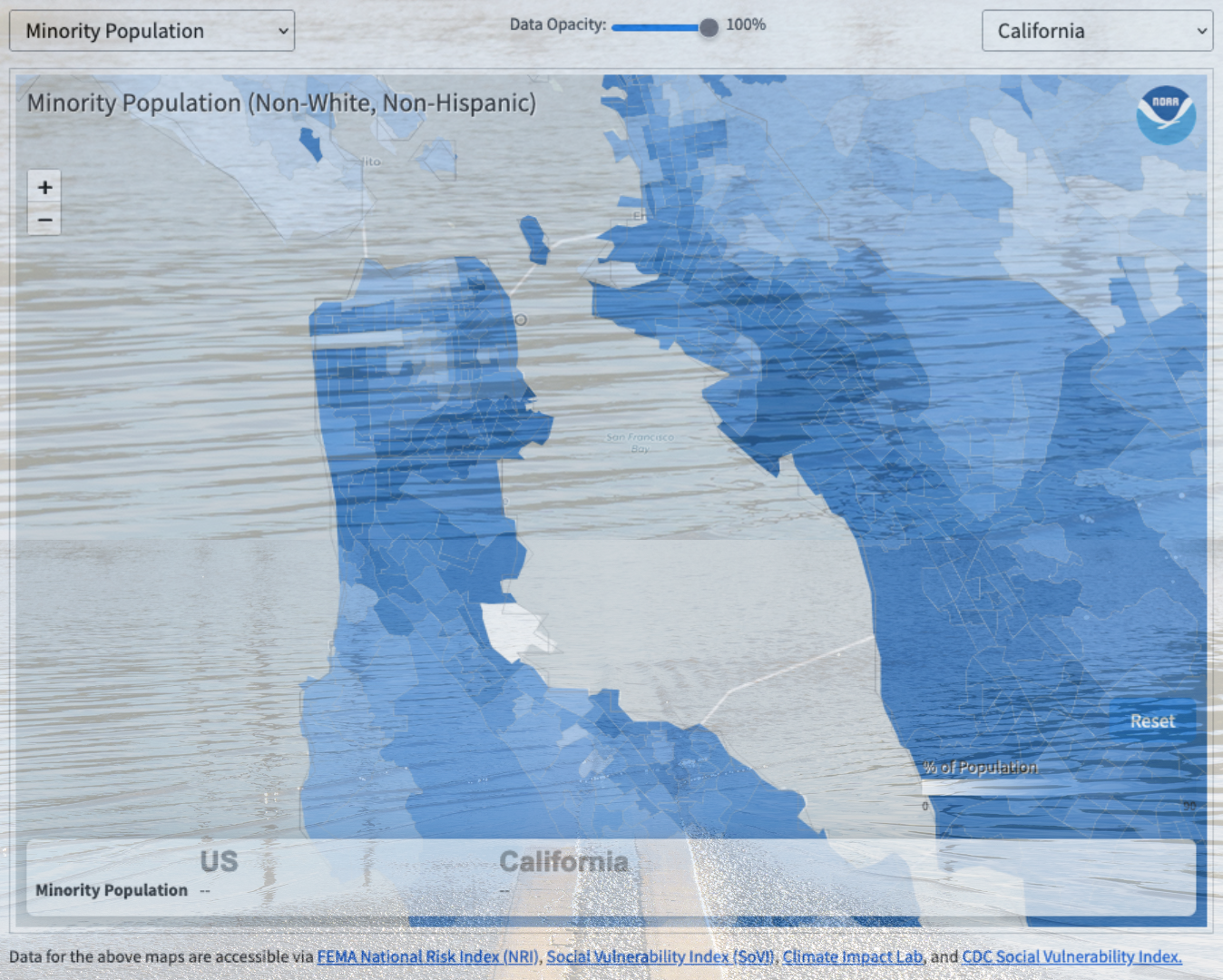

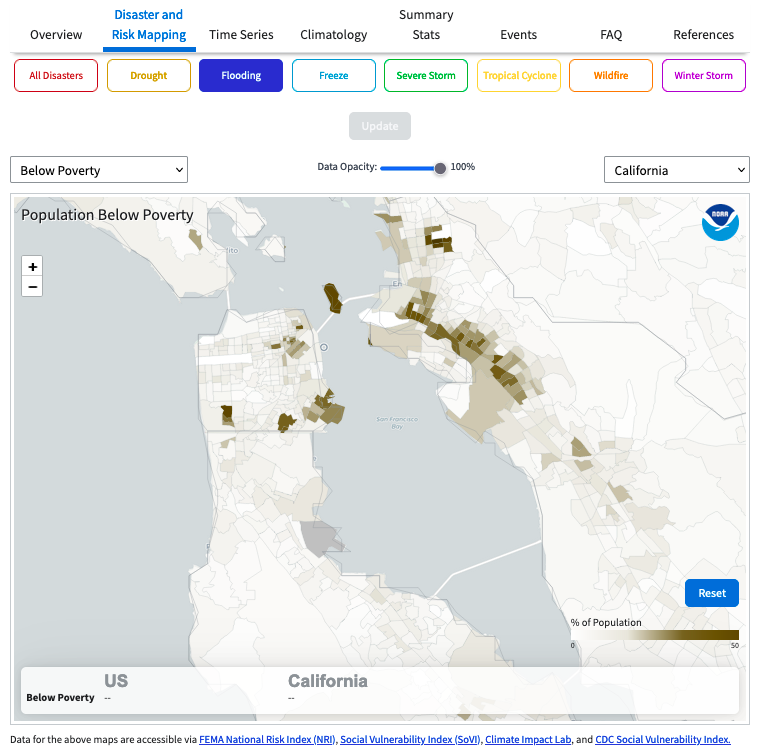

With the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s recent update to their long-running Billion Dollar Disaster Map, urban planners and citizens can see for themselves how disaster risk and vulnerability vary at the much finer “census tract” scale, representing about 4,000 people in a geographic area. Using the tool to look at “hazard risk” and “social vulnerability,” one can see how frontline communities like San Jose’s Alviso, Marin City, the San Rafael Canal District, East Oakland, and others stand out in stark contrast to the wealthier, whiter neighborhoods around them. The tool shows which census tracts have a significant number of people with characteristics that contribute to social vulnerability — for instance, those without vehicles, senior citizens, or the mobility-challenged. Or race, income, and educational level, which correlate with lower access to essential government programs and services that are essential to helping people and communities rebuild after a disaster.

As risk maps go — and there are an overwhelming number out there — NOAA’s is still a little clunky. The census tract view is hidden in a drop-down menu above and to the right of the map, and to look at historic flood hazard risk one has to manually de-select all six other hazard types. The Bay Conservation and Development Commission’s regional Community Vulnerability map is even more granular, analyzing vulnerability at the small “census block” scale (geographic areas of 3,000 people or less), and it also indicates contamination exposure. But hopefully NOAA’s update represents progress toward seeing pre-existing risk and vulnerability disparities within a city or county, and taking ameliorative steps before the next disaster exposes and widens them.

Other Recent Posts

Gleaning in the Giving Season

The practice of collecting food left behind in fields after the harvest is good for the environment and gives more people access to produce.

New Study Teases Out Seawall Impacts

New models suggest that sea walls and levees provide protection against flooding and rising seas with little effect on surrounding areas.

Oakland High Schoolers Sample Local Kayaking

The Oakland Goes Outdoors program gives low-income students a chance to kayak, hike, and camp.

Growing Better Tomatoes with Less Water

UC Santa Cruz researchers find the highly-desired ‘Early Girl’ variety yields more tomatoes under dry-farmed conditions.

Santa Clara Helps Homeless Out of Harm’s Way

A year after adopting a controversial camping ban, Valley Water is trying to move unsheltered people out of the cold and rain.

The Race Against Runoff

San Francisco redesigns drains, parks, permeable pavements and buildings to keep stormwater out of the Bay and build flood resilience.

Learning the Art of Burning to Prevent Wildfire

In Santa Rosa’s Pepperwood Preserve, volunteers are learning how controlled fires can clear out natural wildfire fuel before it can spark.

Martinez Residents Want More Than Apologies — They Want Protection

After a 2022 release of toxic dust and a February 2025 fire, people in the northeast Bay town are tired of waiting for safety improvements.

Weaving Fire Protection Out Of What’s Already There

A new Greenbelt Alliance report shows how existing vineyards, grasslands, and managed forests can slow wildfire and save vulnerable homes.

Fall Plantings Build Pollinator Habitats in Concord

Community groups, climate advocates and a church are coming together to plant pollinator gardens as monarchs, bees see population declines.