Looking for Justice at the Nexus of Housing and Climate Policy

Community demand and decades of organizing resulted in the Casa Adelante project in San Francisco’s Mission District, creating both a public park and affordable housing 2020. Image: MEDA.

How housing is built and who it is built for are not only equity questions, but also climate mitigation questions. When people can afford to live near their jobs, their day-to-day fossil-fuel emissions from commuting go down.

As Californians rebuild and relocate after fires and floods, climate change is making the state’s affordable housing crisis even worse. Millions of state dollars have recently been marshaled towards affordable housing in the San Francisco Bay Area alone, but more housing is still needed. “Smart growth” strategies are often framed as solutions for both emissions and affordability, but if not done carefully and in sync can backfire on both fronts.

KneeDeep Times asked two veteran housing activists to reflect on where long-standing “smart growth” efforts fall short, how climate resilience and social equity change the equation, and what policymakers should try instead.

Fernando Martí and Peter Cohen have a combined 50 years of experience in urban development and housing issues through organizations like Urban Ecology and Greenbelt Alliance, and as former longtime co-directors of the Council of Community Housing Organizations. In 2022 they helped in drafting San Francisco’s Proposition E, an incentive policy for development of mixed-income family housing as well as 100% affordable housing, that drew heavy opposition from business interests and ultimately didn’t pass. Martí and Cohen are also currently involved in proposals for new state housing policies including SB 225 and AB 919, which they also expect to garner strong resistance from conservative interests. Over their careers in housing policy, they have not shied away from big ideas or bold campaigns, whether win, lose or draw. Their responses to KneeDeep questions have been abbreviated.

Fernando Martí (left) and Peter Cohen (right).

Q: What does being smart about urban growth and housing development have to do with climate change?

A: There’s a very basic and intuitive connection between housing policy — which is in essence development policy — and climate change, in that private vehicles are a major cause of the greenhouse gas emissions inducing climate change. So the more often and the farther people drive for their employment, education, groceries and lifestyles, the more emissions are produced. And if you do the math — the Bay Area has about seven million people and California about 39 million — that’s a lot of emissions every day, day after day.

“Smart” housing policy puts new development closer to city and town centers rather than sprawling ever-outwards. Research has well established the relationship between infill affordable housing (for low income and moderate-income households, specifically) and significant reductions in auto use and related greenhouse gas emissions, which is a primary driver of climate change.

Q: If putting new housing near transit is logical climate policy on the surface, where do things start to get murky?

A: Unfortunately, gentrification and displacement have undermined the earnest vision of early smart growth advocates. Talking only about “where” housing should be while ignoring “who” gets it, solves nothing either for environmental preservation or for social advancement.

Statistically, lower-income and moderate-income households tend to drive less often, cover less distance, and own fewer cars. Wealthier people drive more often, over greater distances and own more cars than working class and low-income people. Though this may be intuitive, this key fact is rarely integrated into housing or development policy.

Elderly rally against eviction in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Photo: Fernando Martí.

Negative vehicle emissions nearly triple when upper-income newcomers gentrify and push lower- and moderate-income households out of transit rich central areas. Most new residents drive their cars (even if they’re Teslas!) more than they take transit, so it isn’t really a win for the climate.

Note that this doesn’t mean we should NOT have market-rate development close to transit. But as long as the new development continues to be out-of-whack with the affordable housing need and as long as existing lower income tenants and homeowners face precarious conditions to the stability of their housing, then primarily market-rate transit-oriented development is simply a recipe for further fueling gentrification and a resegregation of the Bay Area.

Q: Smart growth and affordable housing goals have been around for decades, what’s changed?

A: Back in the 1990s, “inclusionary housing” was the big thing for smart growth. To get some affordable housing units built, local governments have often tried a mix of development incentives for market-rate investors — with the hope that the resulting denser projects will have lower rents — and “inclusionary housing” laws to get market-rate developers to add a small percentage of affordable units into their buildings.

Advocates believed that if they could at least get 10% or even 20% of the homes in market-rate development projects to be “affordable,” then the smart growth would all work itself out.

Well, 30 years later, data shows that market rate housing development dominates over 80% of all statewide housing production, even though according to the state, 54% of all new housing needs to be below market to be affordable for most residents, from the unhoused and extremely low income all the way up to middle-income households.

It’s not smart growth, it’s segregation growth: a new version of regional class and race segregation. The Bay Area’s most vulnerable are also being buffeted by new climate challenges like extreme weather, bad air, fire, and storm surges — and lack of shelter only exacerbates the impact. Environmental justice advocate Carl Anthony calls this kind of growth Climate Apartheid. And that is not the future we want — or need — for a sustainable Bay Area.

Q: What are the root causes of the disconnect you see between good intentions and unintended consequences on both the climate and affordability fronts?

A: Economic inequality is the core driver of housing insecurity and dislocation, which leads to the inefficient land use patterns and the displacement “churn” that has resulted in negative climate impacts that got us to this point.

The development patterns that led to car-dependent, polluting behaviors were created by the same real estate forces that have created and, ironically, continue to benefit from the housing crisis. In the same crafty public-relations way that fossil fuel corporations are trying to greenwash their profits by adding “sustainable” initiatives to their portfolios, the real estate interests that created the crisis over all these decades now try to claim they have solutions to the crisis — by eliminating regulations! So, while the basic idea of reversing the decades-long pattern of suburban sprawl and “exclusive” communities is good, the forces that influence real policy to get us there have, shall we say, varied agendas.

And beyond the dearth of sufficient affordable housing supply for lower-income households, There is also no longer a development market to serve the middle, because all the money is to be made at the top. Market-rate development investors slow down production when “the rents aren’t high enough.”

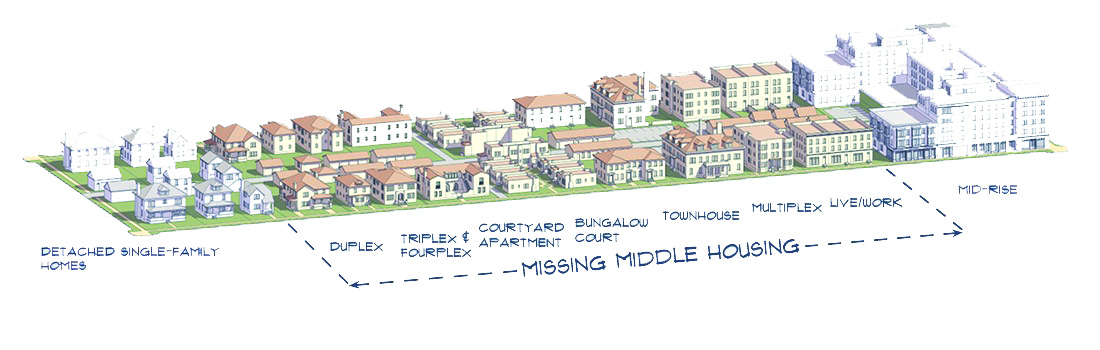

Housing types, ranging from high rises to single family homes, and highlighting the variety missing in the middle from gentrifying Bay Area communities. Art: Opticos Design.

Q: Beyond rents, won’t the climate crisis just increase challenges for the vulnerable?

The communities hardest hit by coming climate emergencies — wildfires, flooding, sea level rise — are the ones with the least resources to rebuild. Think of the low-income residents in Santa Rosa whose mobile home neighborhood was entirely destroyed by the 2017 wildfires, or the immigrant communities in San Rafael’s Canal District, or all the communities of color along the Bay’s low-lying industrial neighborhoods from Richmond to Oakland, from the Bayview to East Palo Alto.

Food pantry held by the Canal Alliance, a community group working on equity issues around the low-income and flooding challenged San Rafael Canal area in Marin County. Photo: Canal Alliance.

These are all communities facing intense affordability and displacement pressures, and all it will take is one major climate emergency for Disaster Capitalism to take away their homes and rebuild a “smart growth” future in its own image.

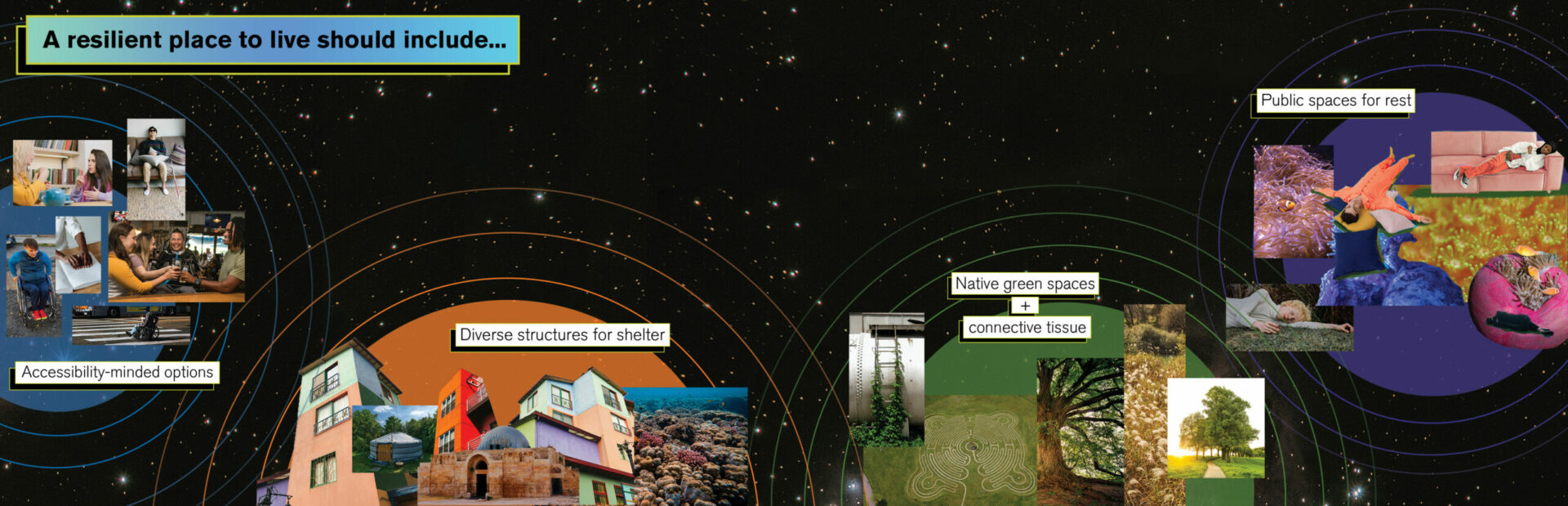

The climate crisis, like the housing crisis and smart growth planning, create opportunities for long-term resilience, but only if led by the most impacted communities themselves, with the support of state-led public investments and regulatory frameworks.

Q: How can we get developers and housing policy more aligned with California’s needs?

Affordable housing needs to be reconceptualized as not only low-income housing, but as housing for the entire array of working households that have been shut out of the private real estate market. Policymakers have only recently started embracing the term “social housing.” Social housing is affordable to a broad range of people, from lower to middle-incomes. This new housing system needs to go beyond the current “low-income housing tax credit” financing system, which is kind of a straightjacket precluding any real innovations in housing policy, and supported by new financing systems, from new tax revenue to public banking infrastructures.

We also have to avoid creating a dependency cycle of market-rate development paying for fees to support affordable housing. It’s not only bad policy but it’s also a political trap. While programs like inclusionary housing are needed tools to ensure that new market-rate housing isn’t entirely segregated, it is financially impossible to require market-rate development to fully pay for the 54% or more of affordability that the State of California has obligated our communities to produce and that we need to equitably sustain our population.

Habitat for Humanity constructs eight affordable townhouses in the hipster Diamond Heights neighborhood of San Francisco. The units are available to low-income families who invest significant sweat equity constructing their own homes.

Instead we need a public infrastructure approach to housing, kind of like a “Marshall Plan” mentality with policies and resources to match it.

We also have to stop allowing giveaways by policymakers to private development with little if any public policy “returns.” Like trickle-down economics, we can’t rely on the real estate market to “naturally” spread the benefits. A more aggressive use of public policy “gives” to exact more certainty of “gets” from the real estate industry would be more prudent. For example, a “use it or lose it” provision baked into a city’s approval of a development project linked to incentives (like fast track approvals or a density bonus or fee reductions), would in return require the developer to actually begin building the housing project within a specific period of time or otherwise the approval expires.

This new housing system also needs to be supported by an aggressive land acquisition strategy in all the walkable, transit-rich town centers. We need to acknowledge the limited control that the public sector has on land, especially at a regional level.

Without an eminent domain pathway (not likely to happen in the US any time soon), more practically this will have to begin with dedicated funding for land acquisition, both for developing new housing and for preserving existing affordable stock. Think of it like an urban analog to the way conservation land trusts work, which by combining direct land acquisition and through easements and taxation tools have managed to preserve large swaths of natural spaces outside the urban areas.

The fight for housing justice is the same as the fight for climate justice. When we see laws that purport to be about climate solutions designed by the same corporations that have benefited from energy and transportation policies that led to the climate crisis, we know these corporations are simply trying to carve out a niche for new forms of profit. Policymakers need to begin by listening to — and following the lead of — the most impacted communities themselves.

Q: Given all these complexities and inequities, where should we build new affordable housing in the Bay Area? Can we be smarter about smart growth?

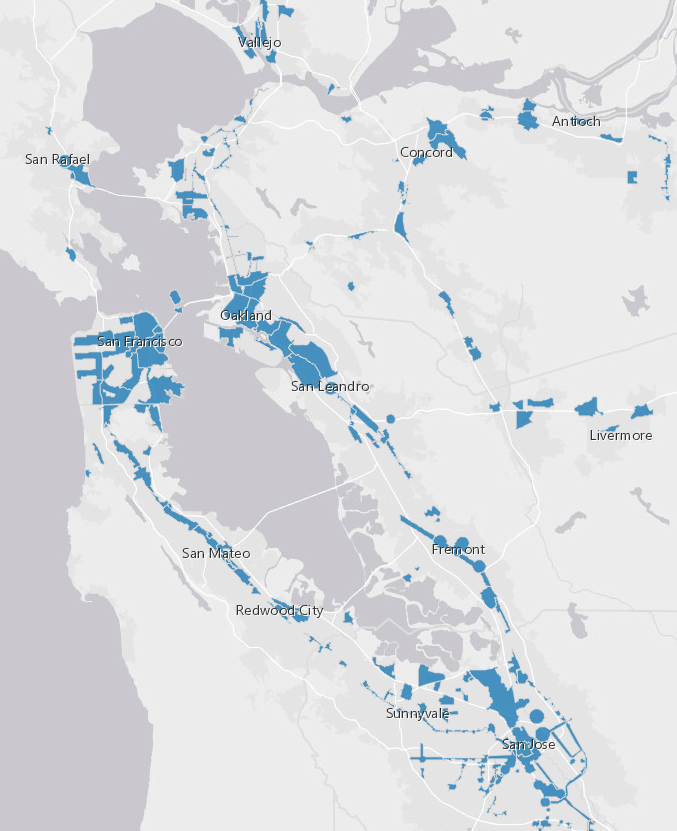

A: The short answer is that infill housing should be built in every community across the Bay Area region, both those that have good access to transit and where bike and car commute times can be relatively short. Affordable infill housing should be part of every city’s climate infrastructure plan and funding.

Essentially it comes down to “Rethinking the Suburbs.” In the last three decades, most of the market-rate development in the Bay Area has been built in “The Big Three” cities of Oakland, San Jose and San Francisco — not distributed more proportionally across all the 100 cities and towns of the region. In fact, the big three often end up with 150% or 200% of the market-rate housing goals assigned to those cities by the State, while development in the suburbs barely meets 50% of the market-rate goals.

That wild imbalance of regional distribution — essentially, that development is highly selective and concentrated regardless of our stated public policy needs — derives from decisions made by developers and investors, not necessarily by the cities themselves.

Precisely where housing development happens within a jurisdiction is paramount. If it’s too far from stores, schools, and amenities, everybody will drive for everything. If it’s too close to industry or freeways or other major noise and pollution generators, there could be nuisances or even health and safety hazards. And of course, if it’s on lowlands or compacted fill near the Bay or up a steep hillside or near an urban/wildland interface, people could be vulnerable to sea rise flooding and fires and slides and quakes.

Priority development areas in Plan Bay Area 2050. Source: MTC.

It’s really important that we do this next generation of housing policy and housing development “right” when it comes to the most appropriate locations for building up our communities, not treating the landscape like one big blank canvas.

This includes both creating new multi-family housing appropriate to a small town scale — what some architects and planners now call “gentle density” — and densifying single-family areas with more modest-size homes and infill ADUs, duplexes and fourplexes. If policies to add ADUs or transform these homes into duplexes or fourplexes are not going to become simply new tools for house flippers to displace communities, then these policies have to be linked to loans and technical assistance support for lower income homeowners.

We also can’t forget to protect existing low-income and working class communities by preserving their existing housing stock as permanently affordable housing.

A dilapidated garden apartment building in Santa Clara, acquired and rehabbed to become affordable housing for transitional age youth and families by Asian Neighborhood Design. Photo: Fernado Marti.

Q: Is the recent movement in favor of “state preemption,” where the state government would force all of the Bay Area to adopt market-rate development, moving us closer or further from climate justice goals in housing?

A: It’s mostly powerful real estate interests that are leading the current round of “state preemption” laws. Just read the list of bill sponsors. Real estate interests know they have less power at the democratically elected local level, so they concentrate on making changes at the state level where politicians are far removed from the local impacts of their votes. This is how we ended up with the California Costa-Hawkins Act, effectively prohibiting local rent control and driving the displacement of communities from neighborhoods targeted for gentrification.

Top-down solutions have never worked well, especially when applied by the powerful to poor and working-class communities. We know this from the history of redlining and urban renewal, and from the siting of polluting factories and the building of freeways through poorer communities.

Vision of housing needs for the displaced. Art: Alyson Wong.

This doesn’t mean there isn’t a need to intervene in racist, exclusionary, and anti-development cities. These demands for intervention often come from low-income communities themselves, who are desperately trying to both stabilize their own communities and find new housing opportunities across the region.

Bottom-up demands from communities have often been in the form of legal and regulatory challenges, citing, for example, the Fair Housing Act or in the form of demands for direct reinvestment into projects and organizations led by the communities themselves. These are the models we should be looking to.

In Part 2 of our Radical Rethink on housing, coming later this year, we will interview next-generation housing activists.

Interviewees

Fernando Martí is a San Francisco-based community architect, housing activist, writer and artist, and former co-director of the Council of Community Housing. Martí, a licensed California architect, has taught housing design studios at UC Berkeley, the University of San Francisco and Cal Poly San Luis Obispo. He was a founding member of the San Francisco Community Land Trust, and currently serves on the board of environmental justice organization PODER, and on San Francisco’s Housing Stability Fund Oversight Board and Public Bank Reinvestment Working Group.

Peter Cohen is an urban geographer and past executive director of the San Francisco Council of Community Housing Organizations (CCHO, pronounced “choo choo”) and policy director at East Bay Housing Organizations (EBHO) in Oakland. He currently works as policy director for Sacramento Housing Alliance. Cohen has been involved in a variety of land use, housing policy and community planning initiatives in San Francisco and other parts of the Bay Area and in statewide coalitions over the last twenty years.