Lighting a Fire Under K-12 Climate Literacy

“Three quarters of our youth describe the future as ‘frightening’ and they are worried that we are not talking about it.”

In a 6th-grade classroom, children are exploring their power — specifically, their own ability to make fossil-fuel-free wind energy. Beneath festive banners of Halloween skeletons, a small sea of handmade windmills race to see which group can generate the most electricity, as teams of children tweak the designs of their windmill blades. Cries of “It’s going faster!” and “We’re up to 8.6!” blend together as the kids monitor hand-held volt meters.

“This lesson is one of the ways we hope to spark an interest in students about climate change at the same time reassure them that there are many people and organizations in our community that are working every day to find solutions and that they can get involved too,” says visiting instructor Trisha Meisler with Sonoma Water. She has come to this school — Sonoma Mountain Charter in Petaluma — as part of the agency’s program to lead both field trips and in-class experiments that educate children about climate and the environment.

Wooden generators used in Sonoma Water windmill experiment. Photo: Jacoba Charles

A Bumpy Road

While climate change is a hot topic among adults, the process of integrating the subject into mainstream K-12 education has been a slow one, says Andra Yeghoian of Ten Strands, an advocacy group promoting environmental and climate literacy in public education.

Teaching climate change has been a required part of grade 6-12 curriculum since 2018. In 2023 Assembly Bill 285 expanded that requirement to lower grades as well, and emphasized that it be included in curriculum at all grade levels. However, the actual implementation of those laws is left up to individual districts, schools, and teachers — with essentially no oversight, support, or feedback provided.

“California is ahead of many other states in terms of having a solid policy foundation — it would be hard for someone to come in and say, ‘you shouldn’t be teaching about this’. But the work that needs to be done is on scaling and implementation,” Yeghoian says.

And that comes back, as so many things do, to school resources. The majority of educators and administrators are interested in expanding environmental literacy, according to a year-long survey conducted by the California Environmental Literacy Initiative, Ten Strands, and The Lawrence Hall of Science. However, they face challenges including a lack of adequate curricular materials and professional development opportunities.

Photo courtesy Ten Strands

“[Teaching climate change] requires a shift in teaching methodology, and administrators who support its development with time and funding for teachers to make those shifts,” says Kirsten Franklin, a retired 4th-grade teacher who now is the Environmental Literacy Coordinator for the Petaluma City School District.

Many teachers and administrators are not even aware of last year’s bill, though the mandated change in curriculum is already supposed to be in effect.

Even those who do know of it then face the challenges of not only becoming familiar with the subject themselves, but then they must find a way to add it to their already overloaded teaching requirements. One method that Franklin hopes will become more widespread is to incorporate climate education into existing lesson plans. “The topic can cover so many subject areas and standards at the same time in highly engaging and meaningful ways,” Franklin says. One example she offers is that when atomic and molecular models are introduced in middle school, lessons could include discussions of the carbon cycle, alternative fuels, and energy transfer.

Lessons can also teach ways that climate change intersects with students’ lives, says Janis Chun, a 5th-grade teacher at Prospect Sierra School in El Cerrito. “[We do a] carbon footprint of food and textiles project that shows them all of the carbon emissions from the very start of production to when the product finally reaches them.”

Evaluating Progress

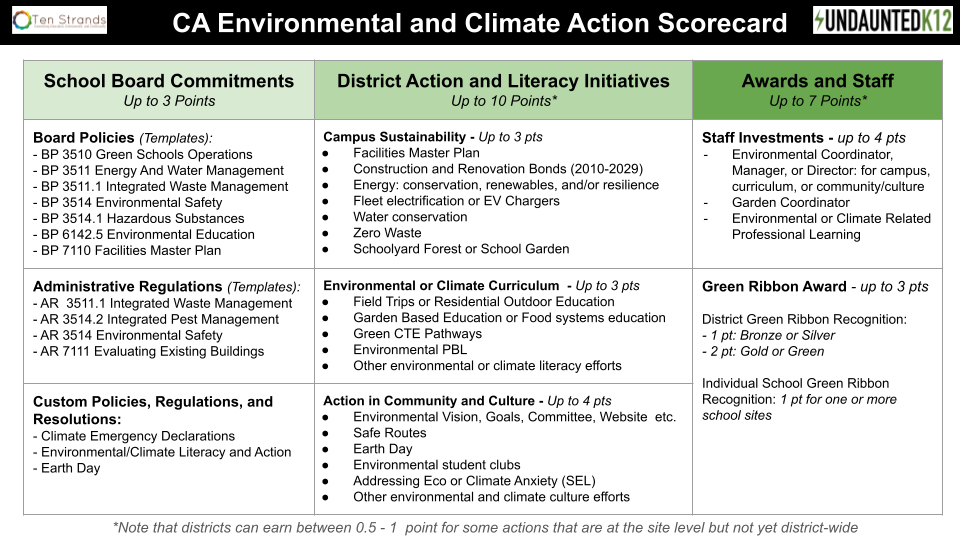

Ten Strands has recently created an environmental and climate action scorecard, which evaluates school districts statewide according to a suite of factors ranging from school curriculum content, staffing choices such as having a dedicated environmental or garden coordinator, board policies, and whether a district — or any of its schools — has achieved Green Ribbon status (a nationwide award that is based on resource efficiency, health and wellness, and environmental sustainability).

Scorecard: Ten Strands

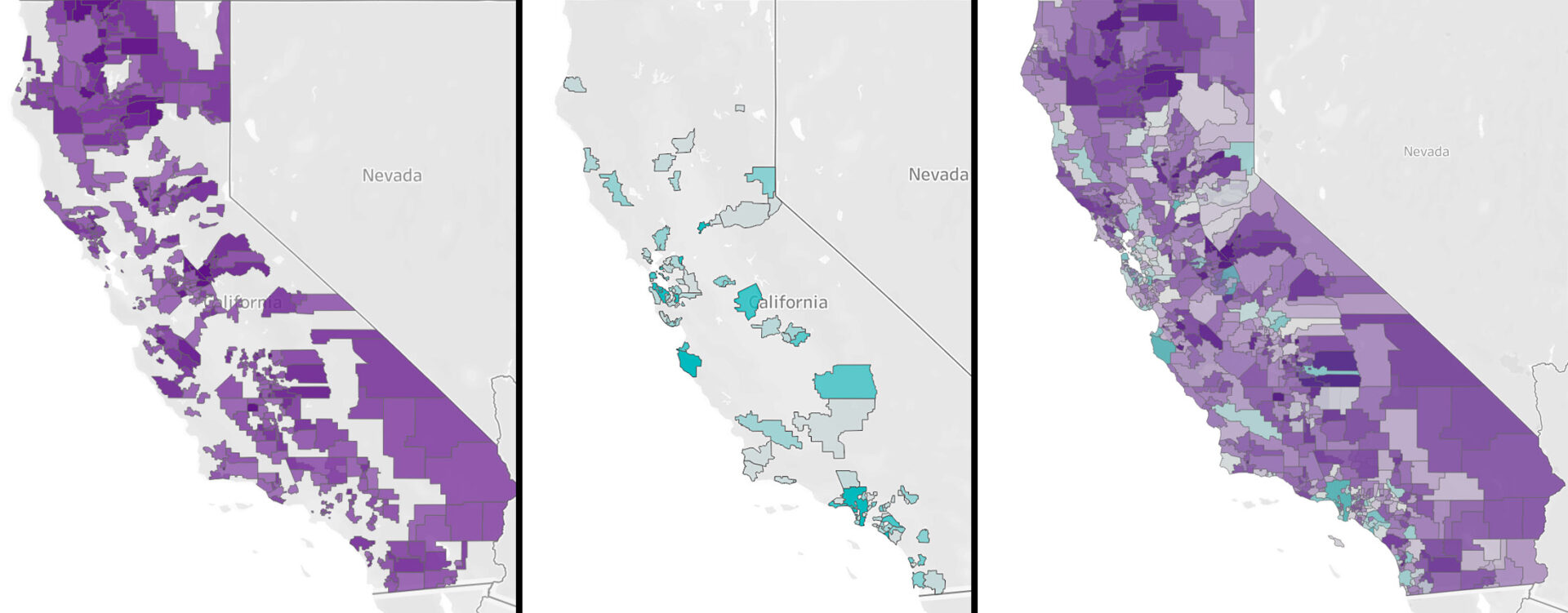

Based on their analysis, 411 of California’s 939 districts did not make it out of the bottom quarter of the scorecard. Conversely, only 18 achieved greater than 75% on the scorecard, and only 104 scored over 50%. The majority of those districts were grouped around either the San Francisco Bay Area or Los Angeles area.

“Most kids that I work with don’t learn about the environmental and climate crisis in a serious way unless they are able to take AP Environmental Science, which isn’t usually offered until 10-12th grade, and isn’t even available at every school,” said Yeghoian. “For those that do get to take it, I often hear them ask, ‘Why is this the first time learning about this?’

Of course, not all aspects of a school’s curriculum will appear in a data survey as large as Ten Strands’ scorecard. To take one example, the Petaluma City School District is in the final days of submitting its application to become a Green Ribbon district.

Results from Ten Strands scorecard analysis statewide. Left: Districts scoring in the bottom 25%. Middle: Districts that achieved over 50%. Right: Combined statewide results.

Although currently getting only 8 out of 20 points on the scorecard, the district is not only pursuing Green Ribbon status, but also is actively working to improve and expand their climate and environment curriculum. They have an active Environmental Literacy and Climate Action Committee that is regularly attended by city government officials, and an environmental science coordinator. They also included teaching climate change, and the most recent laws, in their professional development sessions.

Next, they are considering doing a district-wide energy audit and surveying students and families about climate education and actions, says Dan Osterman, head of the district’s Climate Action and Environmental Literacy Committee.

“We’re hoping this can add to the movement of bringing science more into the center lane and making climate change education connections across the (curriculum) spectrum,” says Osterman.

While progress is slow, those involved in climate education are generally optimistic. School districts are working to move from policy to action.

“We are seeing positive movement in all regions of the state. Is it fast enough? No. Is it reaching every student yet? No, but the momentum is building,” Yeghoian says.

Balancing Anxiety and Action

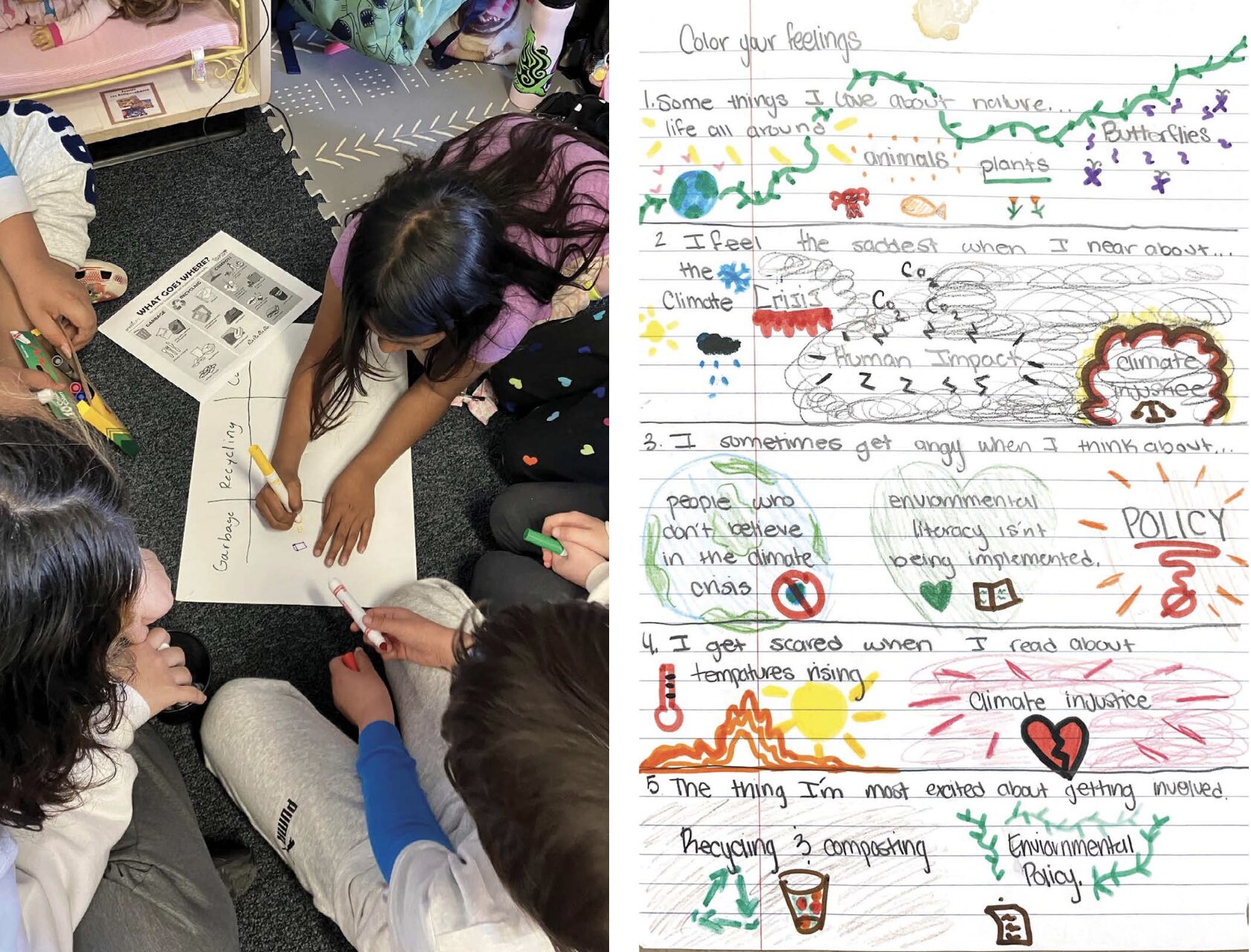

As teachers do approach climate education, many are aware that they don’t want to overwhelm their students with negativity.

“At the elementary level, we really look at what’s appropriate developmentally,” Franklin says. “We empower students through connecting them with the outdoors and nature, so they learn to see what’s happening in the environment that’s around them.”

Nature journaling at Prospect Sierra High School in El Cerrito. Photo courtesy Prospect Sierra School

This foundation can lead to students recognizing human impacts on the natural environment, and how to mitigate and be resilient within that.

“When I ask students, ‘Has climate change affected you,’ their answer is usually an automatic no,” Meisler says. “But then we talk more they will say their house burned down in a wildfire and they had to move, or that their friends moved away. Then we talk about smoke days and extreme heat affecting things like sports and the conversation does come around to, ‘Oh, yeah, I guess it does affect us.’”

Chun’s class also talks about how climate relates to the wildfires that have impacted so many in California. “This can feel scary and bring up a lot of feelings,” Chun says, adding that she likes to inform students on how they can be part of the solution. “We write letters and promote green projects around the school,” she says. “Students can also join the student green council to help incorporate more green initiatives at school.”

Another teacher at Prospect Sierra School, Jesse Feldman, includes lessons on the Endangered Species Act and progress on curbing emissions to show that positive change is possible, and to highlight effective partnerships between government and scientists.

“There is definitely a lot of climate anxiety [among our students]. There is less optimism or action. As a school we need to build more tools to activate hope,” Feldman says.

However, some teachers see an environment of hope in their classrooms. “When I talk with my secondary students about climate change, I don’t see the big anxiety that [people] talk about,” says Lee Boyes, a high school chemistry teacher at Petaluma High in Petaluma. “I see students more positive about their ability to change the path of climate change than say 20 years ago, when it really did feel doom and gloom.”

“This is a very critical issue for students,” Osterman says. “Three-quarters of our youth around the world describe the future as, quote, ‘frightening’, and they are worried that we are not talking about it. We should be learning about math and English and social science through the lens of climate change. It is tough, it is political, but we have to move on.”

Isabella Eclipse contributed to reporting for this story.

KneeDeep would like to repackage its locally relevant climate stories for students and teachers. If anyone is interested in attending a community listening session or two on what would be most useful to educators, please email the editor.

Deeper Dive?

A Short History of California’s Environmental & Climate Ed Policy

California began to prioritize environmental education in 1951, with a bill authorizing outdoor and conservation education. This was expanded in 1976, when the education code was expanded to require that all grade levels be taught environmental facts “as they relate to each other, rather than as isolated bits of information. Students should become aware of the interrelated nature of living processes, gain understanding of ecological relationships and of the effect of human activities upon these relationships, and become sensitive to the interdependence of man and natural resources.”

In 2003, California required that curriculum include a suite of ideas dubbed Environmental Principals and Concepts (EP&Cs) which highlight the deep relationship between humans and the natural world, and are intended to be “big ideas” that inform standards-based instruction and fuel student inquiry. A 2005 law required that these concepts be included in teaching frameworks as well as in textbooks for not just science, but also social science and English language arts. Later legislation incorporated the EP&Cs into the revised California History-Social Science Framework and the California Next Generation Science Standards, and also required that the EP&C’s also be covered in mathematics, visual and performing arts, and health.

The California Childrens’ Outdoor Bill of Rights was signed by the governor in 2007, to “encourage parents, educators, and other concerned citizens to do all they can to help our state’s children experience and enjoy the wonders of Mother Nature.” An environmental literacy task developed a Blueprint for Environmental Literacy in 2015, which provides guidance for educating every California student in, about, and for the environment.

In 2018, climate change education and environmental justice were specifically added to the Environmental Principals and Concepts in 2018, via SB 720. Senator Ben Allen co-authored this bill, and in 2021 he went on to champion legislation that allocated $6 million to fund the creation free educational resources on climate change and environmental justice.

2023 saw the passage of AB 285, which mandates that climate change education be covered in grades 1-5 as well as 6-12. It calls for lessons to include “material on the causes and effects of climate change and methods to mitigate and adapt to climate change” and that these shall be offered to pupils as soon as possible, commencing no later than the 2024–25 school year.

Summary courtesy data provided by Ten Strands.

Resources Behind This Story for Schools and Educators

For more examples of Bay Area schools actively building climate literacy programs, see the Berkeley Unified School District and the San Mateo Office of Education.

Berkeley

- The BUSD Board of Education unanimously passed a Climate Literacy Resolution on November 3, 2021 – becoming the first District in the nation to do so with funding (Berkeleyside). The Board of Education approved $65,000 to fund the first 18 months of curriculum development. The Climate Literacy Resolution also led to the creation of the Climate Literacy Teacher on Special Assignment (TSA) position in the 2023-24 school year.

- Currently there is not a district-wide adopted climate literacy program, but the Climate Literacy Working Group is developing a curriculum. A new committee consisting of staff, students, parents, and community partners will review their programs and build a long-term “Road Map for Climate Literacy”.

San Mateo

- The Environmental Literacy & Sustainability Initiative is a partnership between the San Mateo County Office of Sustainability and San Mateo County Office of Education. This initiative provides capacity building support, from technical assistance to professional development for teachers.

- For 9 years, the Environmental Solutionary Teacher Fellowship has been training teachers to teach about environmental issues in a project-based, solutions-oriented way.

- The State of California provided the San Mateo Office of Education with $6 million to create a curriculum on environmental justice called “Seeds to Solutions”. San Mateo is working with the nonprofit Ten Strands to create units for every grade level, which will be released for free in 2025, after they have been field-tested by teachers.

California

- The California Environmental Literacy Initiative (CAELI) provides a directory of community-based organizations that partner with schools to offer environmental education programs, from classroom activities to field trips.

- In 2022, the California School Boards Association published a Climate Change Task Force Report which provides more case studies from school districts across the state. The report also provides sample language that schools can use to publish their own resolution to address climate change.

Looking for Climate Writing Exercise for Your English Class?

Have your Class Write or Draw Quilt Squares!

KneeDeep has a California Climate Quilt where citizens and students and teachers can tell their climate stories.

To see the results of one high school chemistry teacher’s prompts for his classes just go to the menu at the top of the quilt and click:

- Skyline High School

As another example, an elementary school in Marin County did a climate planning project with Y-Plan. With our help, they then asked the students to write about what they’d done. To see that example go to the menu at the top of the quilt and click:

- Laurel Dell Elementary

KneeDeep even includes writing guidelines for students and much more. We’d love to work with you on a class project around the quilt.

Just Email Us