Less Sea Level Rise for Left Coast

Scientists are now more confident we should plan for up to a foot of sea-level rise on the Pacific Coast by 2050 than they were the last time they did the math. That’s because this time when they compared the projections from computer models with projections from actual tide gauges in coastal waters and satellite altimetry (bouncing radar off the ocean surface to measure height changes), they got the same results.

“What’s new is that models and observation-based projections corroborate each other,” says US Geological Survey coastal hazard scientist Patrick Barnard. “We’re getting better at using multiple lines of evidence to support projections.”

The sea-level-rise science, released by an interagency federal task force (NOAA, USGS, FEMA, et al) this February, builds on scenarios in the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Assessment. For the US coastline in general, the report projects an average rise of 10-12 inches within the next 30 years. The East Coast could go higher (up to 14 inches), and the Gulf Coast higher still (up to 18 inches), while the West Coast could be lower (4-8 inches). Scientists were also confident enough about the new, ground-truthed math that they threw out a more extreme earlier projection.

“We’re pretty confident now about what we’ll see by 2050, but after that depends on emissions scenarios and the speed of ice sheet response,” says Barnard, a co-chair of the task force. “The latest science out of Antarctica is that despite observed ice sheet instability, and even if there is catastrophic loss, sea level will likely take longer to respond than what was originally thought possible.

While the near-future news is better for the West Coast than for other coasts, the San Francisco Bay Area will still suffer because so much of its infrastructure is built at low elevations right along the shoreline, often on sinking Bay fill. USGS projects 150,000 people and $50 billion worth of property across California are at risk of coastal flooding given the new 2050 projection. The Bay Area accounts for two-thirds of statewide impacts, says Barnard.

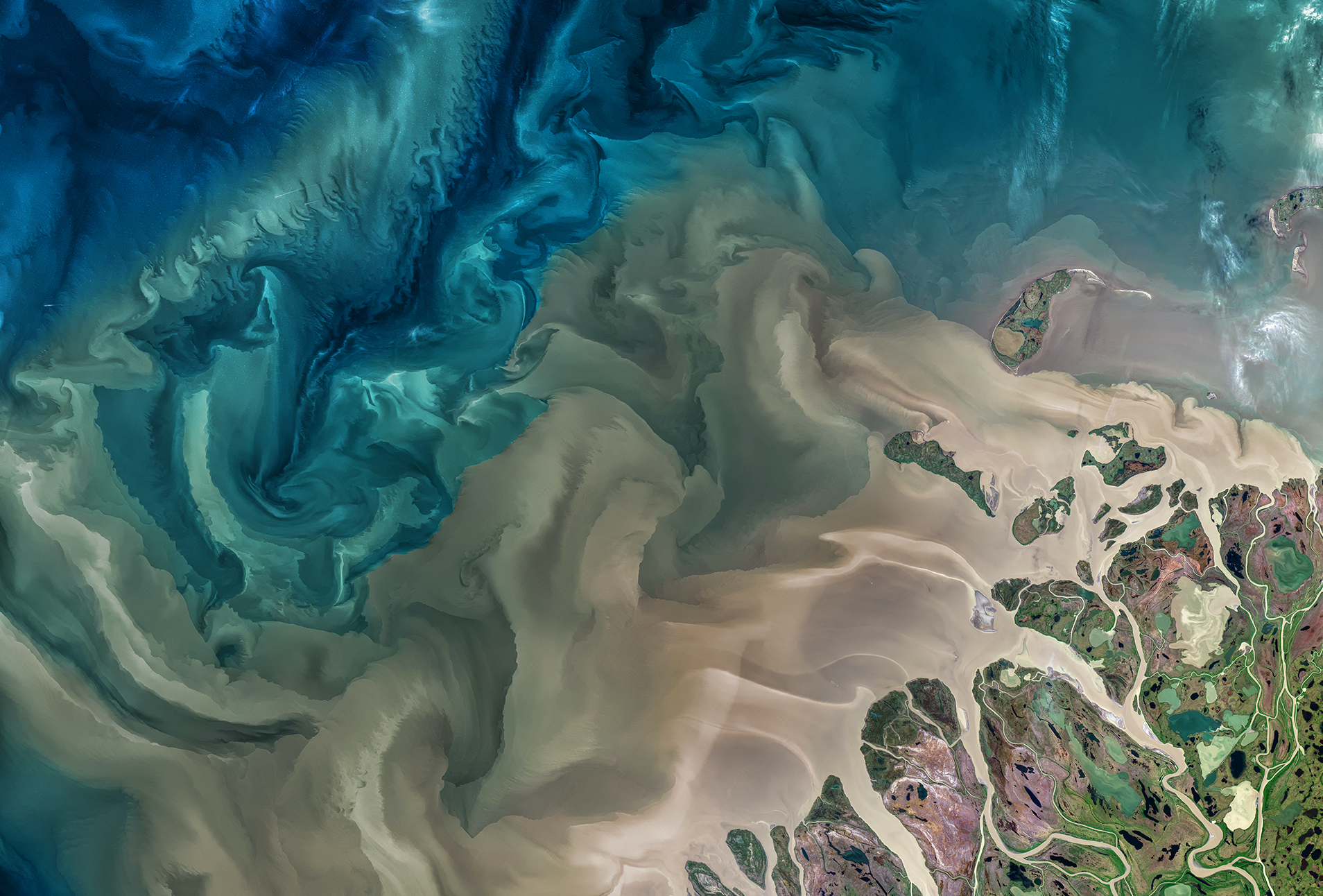

The East and Gulf coasts will be worse off mainly because they are sinking. “They have some of the highest rates of land subsidence in the country,” says Barnard, pointing out the Gulf Coast’s long history of oil and gas drilling and groundwater removal, and both coasts’ big muddy deltas and estuaries “that settle and sink over time.” Warmer water off these coasts also adds more volume to the ocean in these areas that cooler currents off the West Coast prevent.

Another difference in the three coasts is relief. The East and Gulf coasts are relatively flat, with few coastal mountains to stop the advance of storm surges and sea-level rise, and many wide-mouthed estuaries to invite these waters in. California’s coastal mountains, rocky shores, and narrow-mouthed estuaries (like the Golden Gate) reduce some impacts of sea-level rise.

Other sorts of flooding aren’t so stymied by California’s steep shores. The November 2021 atmospheric river over the Pacific sent torrents down hillsides to pool at the base of Marin County watersheds, for example, just where the Bay is also creeping inland, pushing groundwater higher, too.

Other Recent Posts

WRT

WRT is a landscape architecture and planning firm that does climate resilience and adaptation projects.

Gleaning in the Giving Season

The practice of collecting food left behind in fields after the harvest is good for the environment and gives more people access to produce.

New Study Teases Out Seawall Impacts

New models suggest that sea walls and levees provide protection against flooding and rising seas with little effect on surrounding areas.

Oakland High Schoolers Sample Local Kayaking

The Oakland Goes Outdoors program gives low-income students a chance to kayak, hike, and camp.

Growing Better Tomatoes with Less Water

UC Santa Cruz researchers find the highly-desired ‘Early Girl’ variety yields more tomatoes under dry-farmed conditions.

Santa Clara Helps Homeless Out of Harm’s Way

A year after adopting a controversial camping ban, Valley Water is trying to move unsheltered people out of the cold and rain.

The Race Against Runoff

San Francisco redesigns drains, parks, permeable pavements and buildings to keep stormwater out of the Bay and build flood resilience.

Learning the Art of Burning to Prevent Wildfire

In Santa Rosa’s Pepperwood Preserve, volunteers are learning how controlled fires can clear out natural wildfire fuel before it can spark.

Martinez Residents Want More Than Apologies — They Want Protection

After a 2022 release of toxic dust and a February 2025 fire, people in the northeast Bay town are tired of waiting for safety improvements.

Weaving Fire Protection Out Of What’s Already There

A new Greenbelt Alliance report shows how existing vineyards, grasslands, and managed forests can slow wildfire and save vulnerable homes.

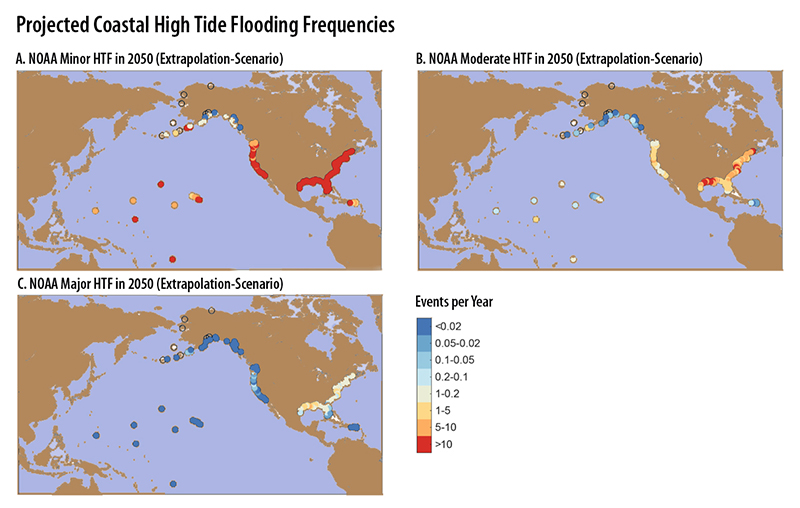

Projected coastal flooding frequencies in the US by 2050. Source: NOAA/USGS.

“Flood frequency is also going to increase exponentially with sea-level rise,” says Barnard. According to the new science, by 2050 damaging flooding will occur more than ten times more often than it does today, or about four times a year as compared to once every three years at present. Though the science also projects flooding will be a bit less frequent in California than on the other coasts, it’s still a worry. “Everything is going to be riding on top of an extra foot of sea level, which could tip the scales in many low-lying coastal communities.”

Everything is also riding on when and how those ice sheets melt, and where in our oceans the melt water ends up. Barnard says just because one coast may be closer to melt sources than another does not mean it will experience higher sea levels — but sorting that all out requires much more complex science.

We can now plan with more certainty for one foot of sea-level rise by 2050. But beyond that is the stuff of politics and the profit motive. Even the best science can’t account for the uncertainties of human meltdown.