Layer Cake of Risk Mapped for Five Bay Area Hotspots

“Greenbelt is trying to create a dialogue on resilience among NGOs, elected officials, businesses, advocacy groups. We’ll see what fruit it bears.”

In the face of a crisis as incremental, complex and vast as climate change, it can be hard to know how and where to take meaningful action on a local scale.

However, a unique approach that considers both environmental pivot points and social equity has recently been developed by Greenbelt Alliance, a conservation organization that just celebrated its 65th year. Their Bay Area Resilience Hotspots project identifies specific locations where nature-based actions will have the greatest effect—both on the climate and on underserved communities.

“Our current patterns of climate adaptation are highly unequal, with adaptation activities happening first in wealthy well-resourced places to protect high value property,” says CC Ciraolo, the North Bay Resilience Manager with Greenbelt Alliance. “Even with all the champions, all the resources, and all the expertise that we have here in the Bay Area, we still aren’t seeing the action that we need in the places that will be most impacted.”

Greenbelt Alliance identified the resilience hotspots by data-driven mapping that found where social vulnerability factors, conservation priorities, and climate hazards overlapped.

“We [reviewed] wildfire risk, flooding, and extreme heat to produce three separate maps,” Ciraolo says. “Next, we partnered with community leaders because we know that successful projects have long term community-based climate champions involved from the start.”

The project is an evolution of a report called At Risk that Greenbelt Alliance has produced every five years since 1989. Historically, the report focused on natural areas threatened by development.

Photo: Karl Nielsen.

The first phase of the project identified 18 hotspots; Greenbelt Alliance then chose five—Gilroy, Newark, Santa Rosa, Suisun City and Richmond—for the initial second phase the alliance is partnering with local climate leaders to develop community profiles that will pilot climate solutions in the five locations.

“The places we started with all represent different resilience challenges, different landscapes of local actors and priorities, and different opportunities to build resilience,” Ciraolo says. “We wanted this to be not just a map that sits on a shelf, but really an action agenda for ourselves and for others.”

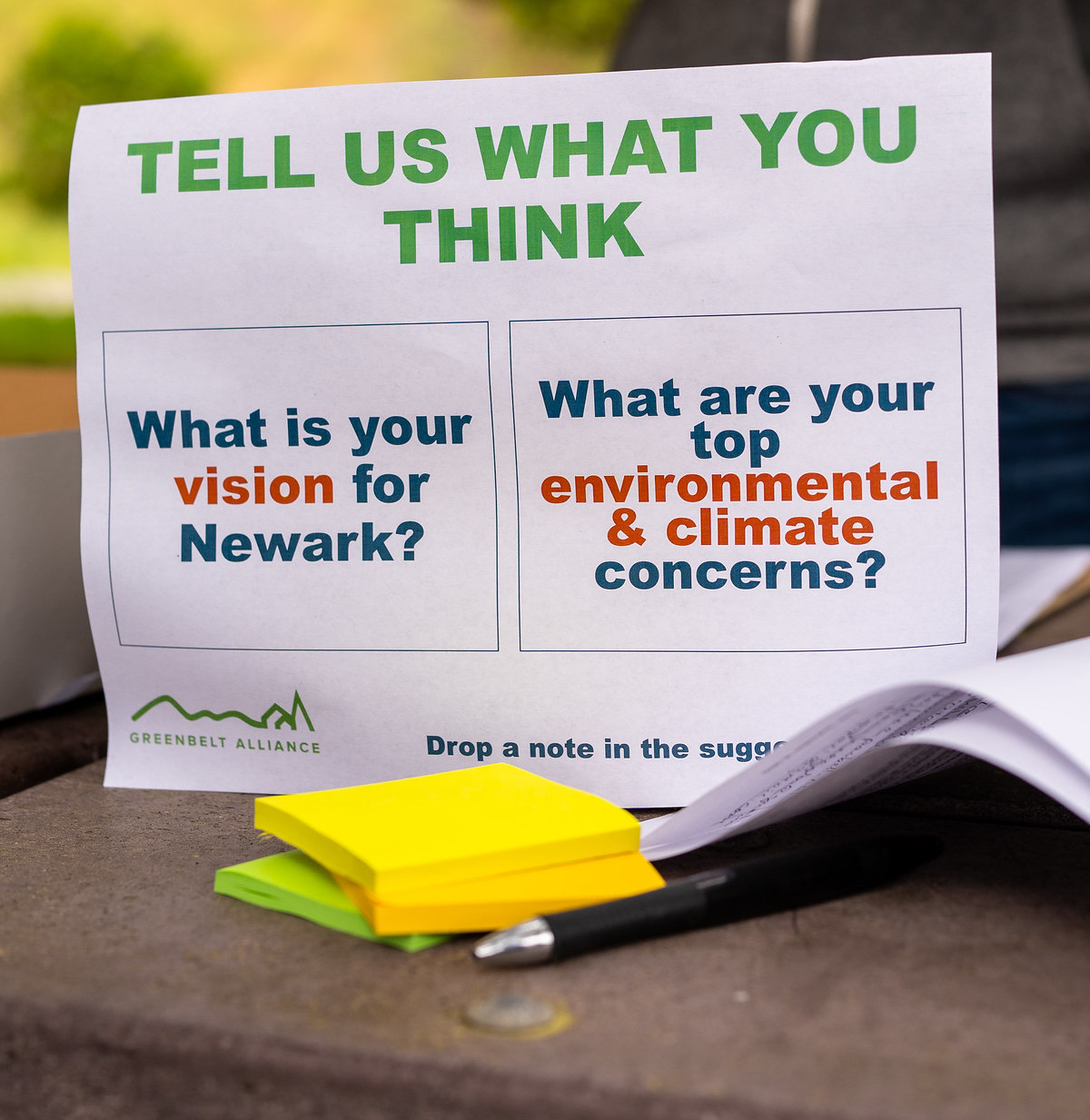

In each community, Greenbelt is forming partnerships to either facilitate community conversations to develop new, or support existing, climate resilience projects; below are a few examples of how.

Photo: Victor Flores

Greening Schools in Santa Rosa

Roseland mural celebrating migration and resilience. Photo: Karl Nielsen.

Southwest Santa Rosa was identified as a hotspot particularly vulnerable to extreme heat, and is home to many who are disproportionately impacted; outdoor workers, renters, youth, and elderly. No major projects are holistically addressing extreme heat in the community, so Greenbelt partnered with the non-profit Latino Service Providers (LSP) which has been connecting and supporting the community since 1989. Together, the two groups hosted community conversations to ensure that any projects met needs and goals experienced by locals, not imposed from the outside.

“[This project] has offered people an opportunity to engage in processes that they perhaps haven’t been invited to participate in before—so that includes our young people, our monolingual Spanish speaking community, our recently immigrated community,” says Stephanie Manieri, executive director of LSP.

The meetings determined an initial course of action: greening schools. Increased green spaces, such as school grounds, will increase shade equity and combat the urban heat island effect that leaves communities more vulnerable to heat.

Later this month, LSP and Greenbelt will be hosting a community event at Bayer Park and Gardens on October 21 to raise climate awareness, to explore more ways to make southwestern Santa Rosa more healthy and livable, and to partake in activities like bicycle-powered salsa making.

Supporting Implementation in Richmond

Urban nature loop and mural in Richmond. Photo: Shira Bezalel.

Schools like this one in Santa Rosa on the farmland interface offer special opportunities to build resilience and equity. Photo: Karl Nielsen.

Sea level rise is poised to exacerbate the flood risks that come with North Richmond’s proximity to two waterways—Wildcat and San Pablo Creeks—and the bay that they drain into. Long before it was added to Greenbelt’s list of hotspots, the community had been actively engaged in pursuing development of a living levee: a nature-based alternative to hardened shorelines. The levee would enhance the ecosystem and provide community benefits such as recreation and aesthetics.

Young people help with trash removal from Richmond creek. Photo: Shira Bezalel.

Last year, the San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority awarded the project a grant for nearly $650,000, funding technical studies and public involvement. This year, a $50,000 augmentation was added for tribal storytelling.

Here, where an explicit plan is already well underway, Greenbelt sees its role as providing support that would push the project over the finish line.

“They were much further along in the process,” Ciraolo says. “But in order to move forward, they really need to figure out a sustainable long-term funding and governance strategy, which is something we have background in. [We know that] there’s a really decent amount of funding and attention growing for climate resilience action, but it is not equally accessible, especially for smaller organizations. Some don’t have the capacity to take in a grant for a million dollars.”

Upping the Political Ante in Newark

Newark ‘s rich baylands. Photo: Shira Bezalel.

Activists have spent over a decade striving to protect a swath of shoreline in Newark from development. Despite their efforts, and in the face of both impending sea level rise and widespread opposition from local scientists and environmental groups, the City has approved development of hundreds of housing units.

“There is a group of us who’ve been active for a long time, but the government in Newark is maybe just now beginning to appreciate that climate change is even happening—and their votes have always been pro-development,” says Jana Sokale, leader of the group Citizens Committee to Complete the Refuge.

New housing going up in Newark. Photo: Shira Bezalel.

To opponents, the issues seem clear: the Newark Baylands is one of the last stretches of South Bay shoreline that is both undeveloped and unprotected. Areas such as this will only become more ecologically precious as sea levels rise, since they offer the only opportunity for the Bay’s wetlands to migrate inland and continue to offer flood protection, and to support ecosystems and species that are both beloved and endangered. And Newark faces additional challenges due to the presence of both rising groundwater and over 50 toxic sites.

“Newark is facing huge risks,” says Ciraolo. “But with that also comes an incredible opportunity to lead the way in reconnecting to the shoreline and to work towards a vision for Newark where nature and people can thrive.”

Shore clean up in Newark. Photo: Shira Bezalel.

The hotspots project takes this opportunity to a new level, Sokale says.

“[Being declared a hotspot] raises the profile of what is at risk regionally,” Sokale says. “What is really interesting is [Greenbelt] looked at raw data and tried to pull it together to give a more complete picture. So you’re seeing social justice, change, housing inequity—all of that in one spot.”

“Sometimes we tend to work in our silos, so I think what they have done is really valuable,” she added. “Now, the question is, what do we do with it?”

Top Banner Photo: Activists, Greenbelt Alliance and BCDC planners gather community input in Newark. Photo: Victor Flores.

More

- Interactive Hotspots Map

- Case Studies for Five Resilience Hot Spots

- Five Threats in Five Places