A Landscape Made to Flood in Sonoma

“It’s a watershed moment in that it provides more site-specific guidance.”

Wooden fence posts poking just above the surface and tall oaks with their trunks submerged are sure signs that the land is flooded. That word, “flooded,” has a negative connotation, an association with destruction. But here it is positive – even protective. And if the San Francisco Estuary Institute, Sonoma County Water Agency, and Laguna de Santa Rosa Foundation get what they want, more water, not less, is destined for this place.

The Laguna de Santa Rosa drains much of urban Sonoma County, a watershed of 250 square miles, and is the largest tributary of the mighty Russian River. The more water that this creek and its floodplain can slow and absorb, the less water will rush downstream to threaten truly catastrophic flooding in Guerneville, Monte Rio, and Rio Nido.

But echoing a familiar Bay Area story, more than a century of development and channelization of the 22-mile Laguna de Santa Rosa and its tributaries – including Mark West, Santa Rosa, and Copeland creeks – significantly impaired the historical carrying capacity and ecological function of the system. The city of Sebastopol discharged its sewage directly into the Laguna until 1978.

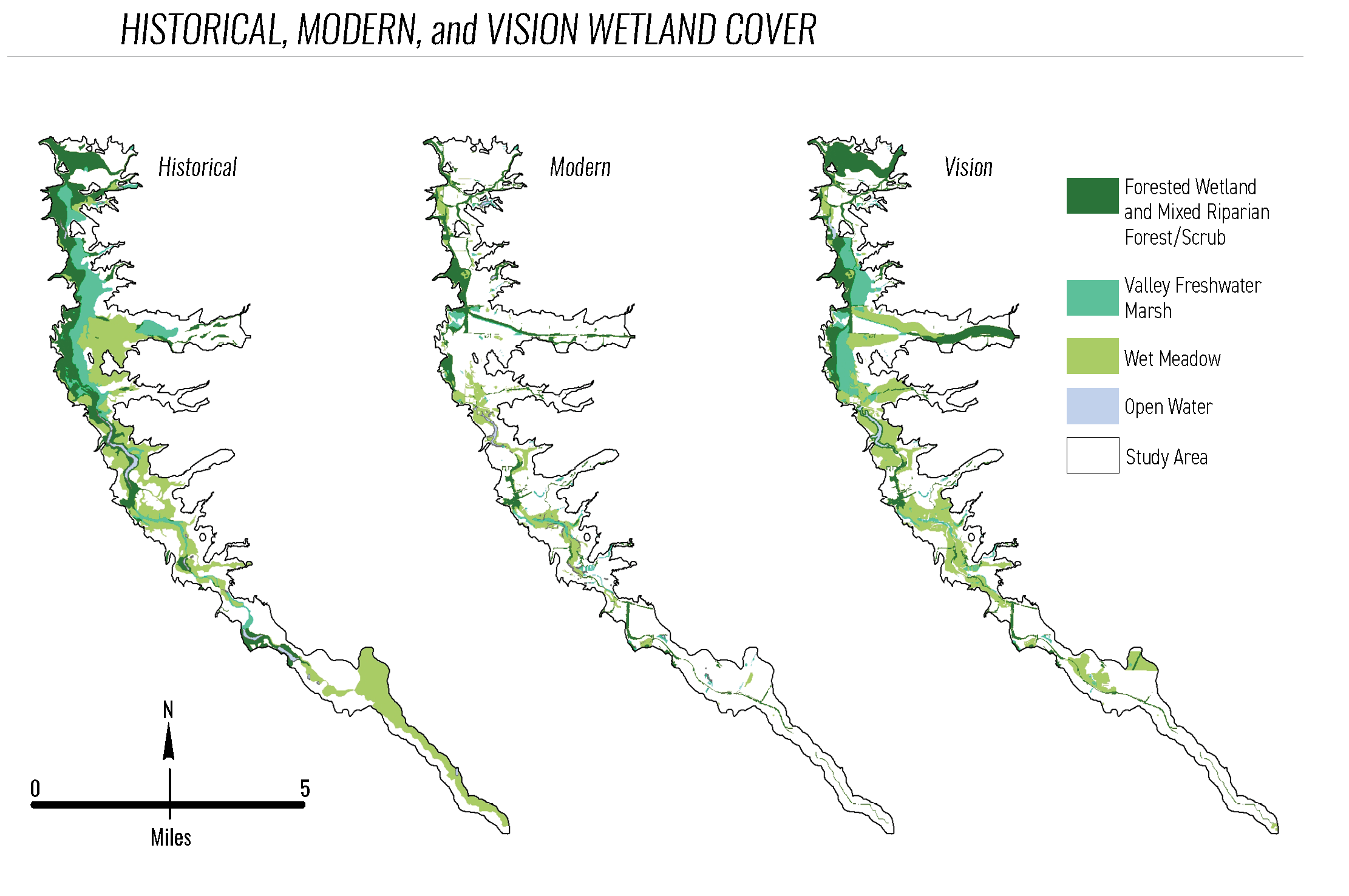

Source: SFEI

Things began to turn around in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when a group of dedicated volunteers launched the nonprofit Laguna de Santa Rosa Foundation and the City of Santa Rosa constructed the Kelly Farm Demonstration Wetland to restore fish and wildlife habitat using treated wastewater.

The next three decades saw many more plans and projects designed to undo or compensate for damage done to the Laguna, or to protect what remained. These were largely piecemeal in nature, though in 2011 the entire complex – now recognized as the largest freshwater wetland on the Northern California coast – was named a Wetland of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, throwing additional weight behind its conservation.

Big Picture in Higher Res

It wasn’t until last month that the Laguna finally saw what many advocates would say it has long needed and deserved: a full-scale, “master” restoration plan encompassing not only the mainstem Laguna de Santa Rosa but also its full floodplain. Set in motion in 2016, the new report is the product of years of work and collaboration between SFEI, the Laguna Foundation, and Sonoma Water, which delivers drinking water from the Russian River to 600,000 people.

“There’s been a lot of restoration going on in the Laguna itself and in the surrounding watershed for quite some time, but there was never an effort to wrap arms around all of that and get it all coordinated and try to figure out, what are we trying to get to?” says lead author Scott Dusterhoff, a senior scientist with SFEI.

The new plan carefully catalogs past and current conditions throughout the system and details six key projects designed to restore some of its historical function within today’s reduced footprint, all while accounting for future climate change.

“I think it’s a watershed moment in that it provides more site-specific guidance,” says Anne Morkill, executive director of the Laguna de Santa Rosa Foundation and a former San Francisco Bay wildlife refuge manager with the US Fish and Wildlife Service. “It gives us something to start a conversation with, whether it’s a public landowner or private landowner, and allows us to quantify what that change might look like.”

To the casual observer, things may not look all that bad at the Laguna today. It still supports migrating coho salmon and steelhead trout; red-legged frog and California tiger salamander; bald eagle and Northern spotted owl; and, in its many vernal pools – isolated ponds that persist on the floodplain following winter rains – endangered California freshwater shrimp.

Yet it faces serious challenges that will only grow as time goes on. Past alterations to the Laguna and its watershed have led to accelerated stormwater runoff from the hills, increased delivery and accumulation of fine sediment and nutrients to wetland channels, introduction of invasive species, and widespread habitat loss, the report’s introduction notes.

Looking forward, rising temperatures and increasingly frequent and severe floods, droughts, and wildfires, combined with expanding development pressure, will likely exacerbate these problems.

A Redo That Undoes

From the Occidental Road bridge outside Sebastopol, the floodplain does appear relatively intact. Winter rains have caused the Laguna to spill its banks and transform into a broad expanse of shallow, flat water – just as it should.

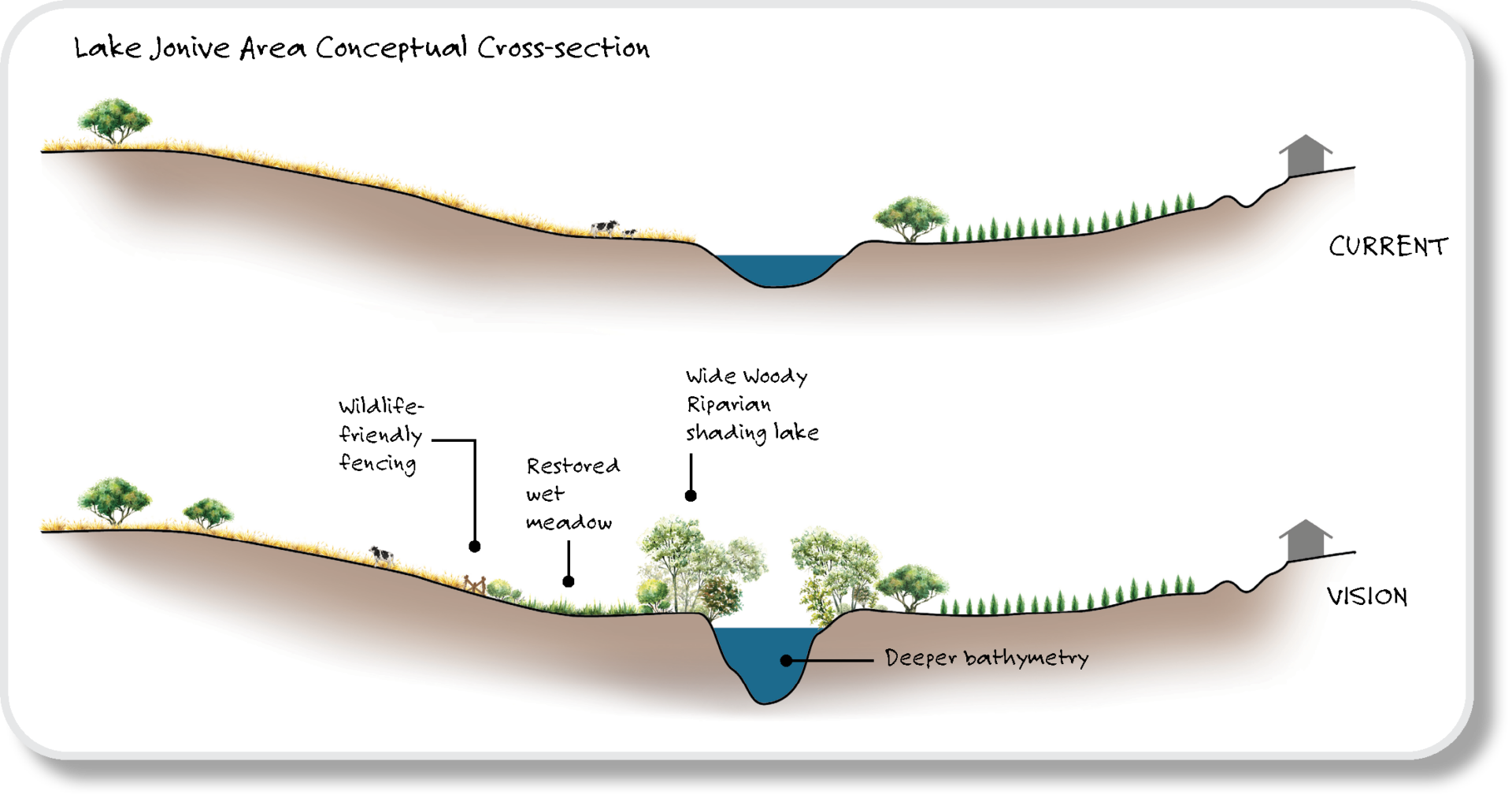

The difference is that this spot once marked the northern end of a long, narrow, and deep perennial lake called Lake Jonive. The lake technically still exists farther to the south, narrower and shallower and bordered by vineyards and pastures. Historically it held more, clearer water year-round and provided cold-water habitat to resident and anadromous (spawning) fish species. The lake was ringed by wet meadow and then a forested riparian zone that provided greater habitat and connectivity, and helped slow water and trap sediment during flood events. That’s why the new report calls for bringing it back.

The restoration of Lake Jonive is one of six high-impact projects proposed in the plan to help restore the Laguna system and, in a sense, fortify it against future impacts. Other projects include realigning and restoring lower Mark West Creek; freeing a channelized and straightened segment of the mainstem Laguna; and bringing back another perennial lake.

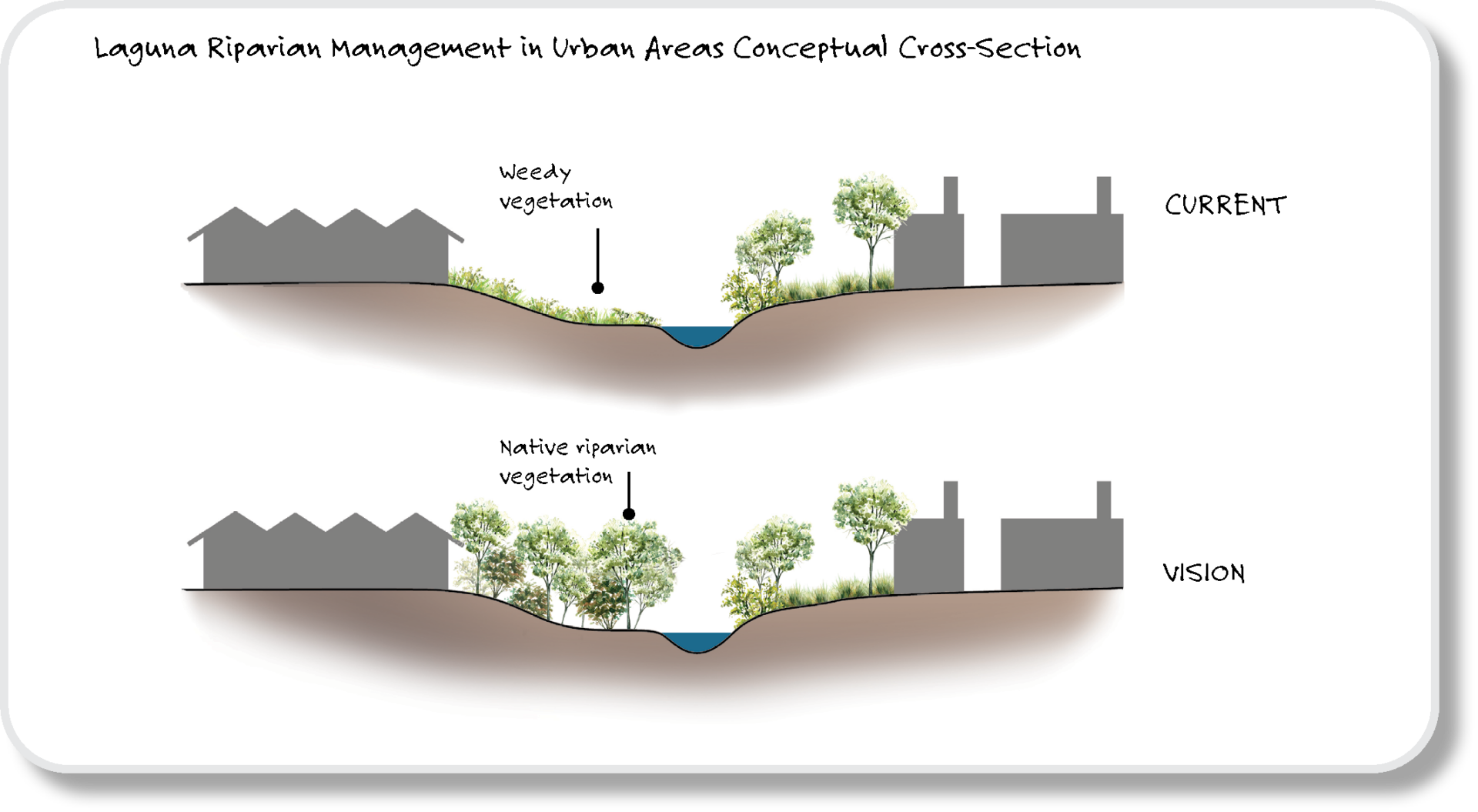

In general this work would widen and deepen the main Laguna channel, improving water quality and water-carrying capacity; return croplands along its banks to native vegetation; and improve links between waterways and upland areas, allowing native species a better chance at adapting to future changes.

Of course, bringing any of this to fruition will require additional funding and finagling of property rights, given that the vast majority of the Laguna floodplain is held in private hands, says Neil Lassettre, principal environmental specialist with Sonoma Water.

And it would all be for naught without concurrent work in the upper watershed, on Sonoma Mountain and the Mayacamas Mountains. Specifically, Lassettre says, this means undoing what are now viewed as past mistakes by restoring flood-control channels and other riparian corridors to a more natural state, helping slow and sink runoff while allowing excess sediment and nutrients to settle out before reaching the Laguna – work that both Sonoma Water and the North Coast Regional Water Board are already undertaking.

The flooded wetland during January 2024 storms. Photo: Nate Seltenrich

Nearly two centuries since an 1833 Mexican land grant first brought farming and ranching to the banks of the Laguna, a hard-won lesson has crystallized in the new restoration plan. This is not a collection of disparate creeks and ponds and savannas and forests, but rather a single, complex system. We perturb it at our own peril, especially with more intense droughts and storms headed our way.

“Ultimately,” Dusterhoff says, “the long-term resilience and improved functioning of the Laguna is going to depend in large part on what’s happening upstream of the Laguna in the contributing watershed.”