Knock-On Flood Threat Gets 4-Inch Reality Check

“The Bay is a complicated bathtub, not a uniform piece of porcelain.”

For years, sea level rise planning in the Bay Area has carried a dark asterisk: Protect your own city with caution, or your seawalls and levees might contribute to flooding your neighbors.

Fears of cross-bay flooding — or inadvertently foisting extra water onto parts of the San Francisco bayshore by defending other areas of shoreline from rising seas with flood walls — have taken on a life of their own in public discourse from San Rafael to the South Bay. But the magnitude of these redirected effects may be far smaller than the public imagines.

“The myth comes from the perspective of flood management along a river, when the narrow channel has little storage,” explains Matt Brennan, a senior engineering hydrologist with Environmental Science Associates, a firm involved in many local sea level rise adaptation projects.

But the San Francisco Bay is not a river or a coastline pounded day in and day out by surf. The ancient riverbeds and valleys that determine the topography of the Bay shoreline allow water more room to spread out in some places than others. Around the edges, boundaries also vary, ranging from absorbent and gradual, like wetlands, to impervious and steep, like concrete seawalls.

“Sometimes this is simplified as, ‘The bay is like a bathtub, and if you raise one side of the bathtub, and you keep filling it with water, then the other side spills over’,” says Len Materman, the chief executive officer of the San Mateo County Flood and Sea Level Rise Resiliency District (also called OneShoreline).

While that analogy makes sense, “it’s [more] context-specific,” he adds. “This bathtub is not a uniform piece of porcelain.”

A stretch of a South Bay levee project protecting downtown San Jose, Alviso, and critical wastewater treatment facilities. Photo: Joey Kotifica

Over-the-Top Science

Mark Stacey’s hands air-trace the edges of invisible seawalls and floodplains as he speaks, the schematics falling off the bottom of his Zoom rectangle. The University of California, Berkeley professor is behind several studies that model how cross-bay flooding could play out with sea level rise, including at least one that’s been cited in public comments urging caution with bayshore protection. He is eager to set the record straight on his work.

“The kernel of truth is that water levels are a little lower if there are no walls,” Stacey agrees. But “the direct displacement of water is negligible.”

Scientists like Stacey compare what happens to the water level at high tide under various future sea level scenarios with one segment of Bay shoreline raised versus what would happen with none of the shoreline raised.

One 2018 paper Stacey contributed to modeled the effects of armoring county by county, for all nine Bay Area counties. The results showed that only after about five feet of sea level rise, in which one county raised its levees to withstand this, would a neighboring county that did nothing receive more than four inches of higher water.

“At most, this implies that the Bay Area should plan together for higher amounts of sea level rise, since regional action will have some minor effects. It does not mean that a smaller regional project, like the waterfront Oakland A’s stadium or a business park in Burlingame that raises a few buildings and the Bay Trail, should be concerned about causing re-directed flooding in counties across the Bay,” Brennan wrote in an email. “I have addressed public comments on draft EIRs for these projects which make these claims, building off the original myth.”

According to his colleague at ESA, Michelle Orr, “It’s more about taking into account the sea level rise adaptation actions of your fellow community members.”

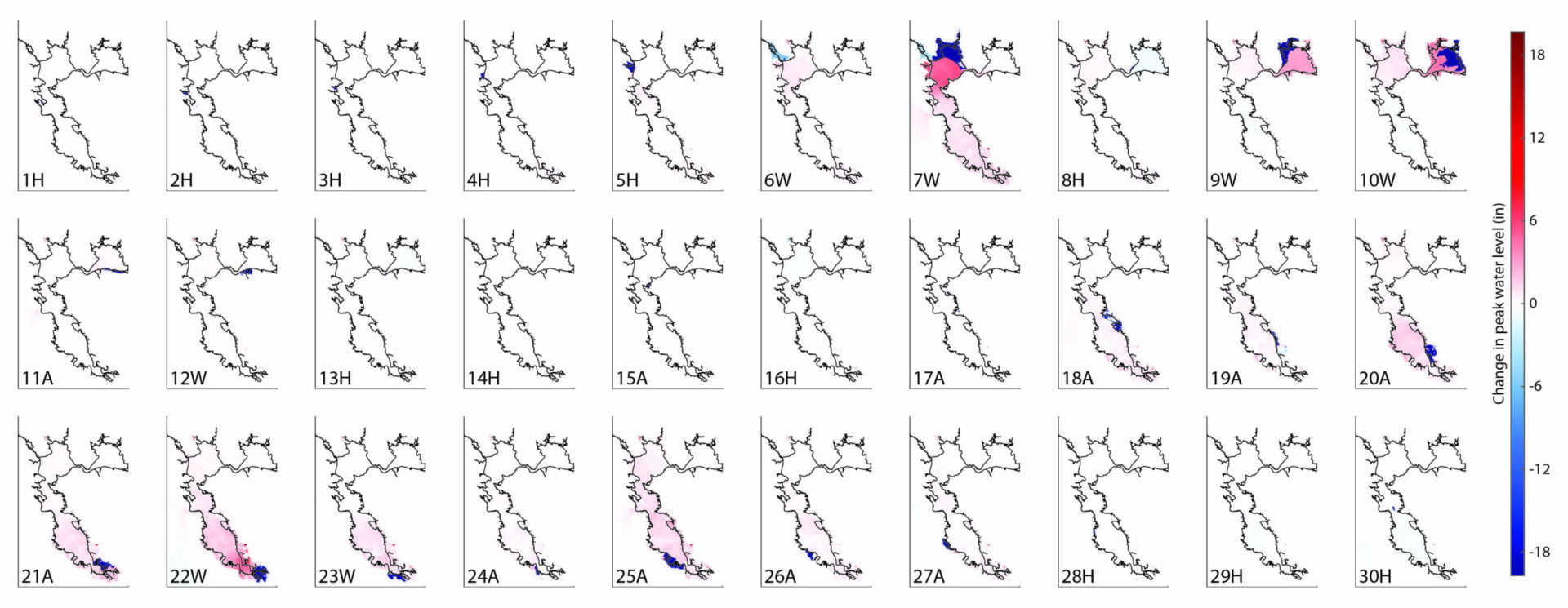

Another study co-authored by Stacey used 30 smaller units of shoreline instead of the nine counties in the modeling. In a scenario with nearly seven feet of sea level rise, redirected flooding in unprotected areas only topped four inches for three of the 30 shoreline units.

Maps of change in peak water levels for each landscape unit (OLU) with a shoreline protection scenario based on more than six feet of sea level rise. The numbers and letters refer to geographic locations and geomorphic types (headlands, valleys, alluvial etc.). Only three of the 30 shoreline protection scenarios would raise the water level beyond three additional inches. Source: Hummel & Stacey 2020

Indeed, these three areas of the Bay are good candidates for reducing — rather than increasing — water levels for their neighbors. The large expanses of wetlands between the Napa River and Highway 37, along the east side of Suisun Bay, and the former salt ponds north of Alviso and San Jose all lie below mean sea level behind levees and floodwalls, where water levels are managed by human interventions. If these areas were to be reconnected to tidal action, they could store a lot more water and even reduce nearby water levels (see chart above).

Even if most of the bayshore decided to wall itself off, Stacey estimates that the unprotected shorelines would receive only a few extra inches of water as a result — 10 to 20 times less than the magnitude of sea level rise the region faces in the coming decades.

Instead of pointing fingers in an arms race to keep out the rising bay water, Stacey hopes that areas open to welcoming the water could be commended, perhaps even financially rewarded by their neighbors for the service of giving up land to allow the rising Bay a bit more room to spread out. The key is deciding where to let the sea in.

Most at Risk

It’s a warm July afternoon at what’s arguably the lowest-lying taco truck in the Bay Area. The lot where it’s parked in Alviso, a San Jose neighborhood in the southernmost crook of the bay, would be long submerged at high tide if gravity and the sea had their way.

It’s one of a handful of communities that are uniquely vulnerable to both rising seas and the side effects of high-tide water levels changing as other parts of the Bay Area protect their shorelines.

But one of the taco truck’s patrons, a lifelong Alvisan, says he hardly worries about the future. Engineering projects in the last few years seem to have cured Alviso of its chronic flooding, from what he’s observed, and the immensity of that feat after the flooding he grew up witnessing gives him confidence in the neighborhood’s future.

Over the years, flood control work around Alviso has actually been a combination of keeping water out and letting it in via the construction of new infrastructure (including the super-strength levee under construction), careful groundwater replenishment to buoy the sinking landscape, and the opening of new areas to the tides as part of wetland restoration along neighboring shorelines.

The region’s largest multi-jurisdiction levee project in recent history near San Jose in July 2024. The project is being built reach by reach (excavation for Reach 2/3 is nearing completion and most of Reach 1 is at levee target elevation above 15.2 feet). The photo looks east and pond A12 is in the foreground. Photo: Brandon Beach, USACE

Materman says that the mindset of looking for “opportunities to create more space for water” is still not normalized but hopes that’s beginning to change.

As Bay Area counties start preparing state-mandated shoreline adaptation plans, they will no doubt have to consider both hard seawalls and opportunities to send excess water into subsided wetland landscapes. In the meantime, the ocean continues its advance.

“We absolutely cannot take our foot off the pedal” for adaptation, says Materman.

While the high-water warnings of re-directed flooding impacts for Bay counties may have faded, the central message is still invaluable for everyone around the bathtub rim.

“The framing of ‘we’re all connected, and if you build a wall in one place, it could flood a community elsewhere’ — that really captured people’s imagination and helped mobilize us to think about planning together,” says Orr.

Top Art: Liana Finck