Photo: Isabella Eclipse

Isolated Town Forges Resilience on Mendocino Coast

When my mother moved to a small town on the Mendocino coast, she welcomed the wide open spaces, rugged natural beauty, and slower lifestyle. She did not, however, expect to get trapped inside her home during storms last winter. Though beset by many of the same climate impacts as the Bay Area, Point Arena has far fewer resources at its disposal. After experiencing severe storms, flooding, wildfire smoke, numerous widespread power outages, and even a snowstorm all in the last three years, the residents of this small, secluded town have decided to take climate preparedness into their own hands. “Humans aren’t very good at preparing for stuff like this [but then] it finally begins to sink in that this is a small area, we all kind of depend on each other,” says Mellisa Hannum, the town librarian.

Extremes-in-3D

A five-part series of stories in which KneeDeep Times explores the science behind climate extremes in California, and how people and places react and adapt.

Supported by the CO2 Foundation and Pulitzer Center.

FULL READ

Isolated Town Forges Resilience on Mendocino Coast

When my mother moved from the Bay Area to a small town on the Mendocino coast during the height of the pandemic, she welcomed the wide open spaces, rugged natural beauty, and slower lifestyle. She did not, however, expect to get trapped inside her home during the atmospheric river-driven storms last winter, when relentless rain turned her steep driveway into a slippery slope of sludge and fallen trees blocked the road. With the power out for several days, the electric water pump in her well stopped working. She waited out the storm with a few jugs of bottled water and a small stock of canned foods.

Though beset by many of the same climate impacts as the Bay Area, Point Arena has far fewer resources at its disposal. After experiencing severe storms, flooding, wildfire smoke, numerous widespread power outages, and even a snowstorm all in the last three years, the residents of this small, secluded town have decided to take climate preparedness into their own hands.

EXTREMES-IN-3D

A five-part series of stories in which KneeDeep Times explores the science behind climate extremes in California, and how people and places react and adapt.

Series Home

Click here to enter

Supported by the CO2 Foundation and Pulitzer Center.

A Small Town on the Edge

Within a short time of moving to Mendocino County, our family learned that although Point Arena is beautiful, it can also feel isolated, especially when bad weather strikes. Getting here is only a three hour drive from San Francisco, but it feels much farther as you take the winding roads north, clinging to sheer cliffs along the coast. The city is built around the harbor in Arena Cove, with California’s famous coastal Highway 1 doubling as the town’s main street.

Charming cafes and boutiques pack Main Street, selling everything from medicinal herbs to handmade wares. The Sign of the Whale is the only bar in town and the best place to learn local news. The Arena Market co-op offers specialty foods and wifi (a good place, I learned, to wait out a power outage). Residents can find most of the necessities on Main Street: a gas station, bank, post office, library, and convenience store. There’s even a historic 1928 vaudevillian theater, several art galleries, and two churches. Still, the nearest supermarket is an hour away. Farther down the street is a small elementary and high school serving 650 students.

Point Arena is home to 460 residents, including now our extended family of five. About 4,430 people live in the immediate environs and district according to the 2020 Census. Adjacent to the town lie the tribal lands of the Manchester-Point Arena Band of Pomo Indians, with a population of 188 spread over 364 acres.

First named “Cape of Fortune” by the Spanish in the 1500s, the town evolved into a bustling lumber port by the 1800s. The rugged shoreline and powerful waves around Arena Cove made it dangerous for ships to navigate. In 1870, after one too many shipwrecks, the locals constructed a 100-foot-tall lighthouse, only to have it fall down in the 1906 earthquake that leveled San Francisco. Both the town and lighthouse were quickly rebuilt. Then, in 1927 a fire destroyed the town and in 1983, the pier in Arena Cove was decimated by a storm. Even then, disasters were a part of Point Arena’s story.

A New Year’s brew of weather. Photo: Scott Sewell

Today the area famously produces cannabis for markets worldwide, but tourism remains at the heart of the local economy. Numerous quaint boutique hotels, bed-and-breakfasts, and vacation homes dot the coast. Many Bay Area urbanites spend their summers in Point Arena, drawn by its coastal setting and small town ambiance. But the coastal comforts don’t extend to everyone; 19% of city residents and 24% of those on the reservation live in poverty.

Grappling with Big Problems When You’re Small

Climate change is increasing the severity of disasters like storms, flooding, and wildfire while introducing new threats like sea level rise to coastal towns up and down California. In our town, no matter what the disaster — fallen trees, landslides, a flood, fire — we can easily get cut off from where we need to go. I remember sitting in the car for hours one blistering summer day, as we tried to flee the smoke from a fire in a nearby town. We, and most of our neighbors, were stuck behind some fallen trees on a one-lane road.

In a large, rural county like Mendocino, resources for disaster preparedness and response are much scarcer than they are in more developed areas. Communication and transportation networks are also easily overwhelmed. When the roads become impassable, it can take days for emergency services to arrive. Those at highest risk of being isolated from the rest of the community by floodwaters or storm debris include elderly, disabled, and low-income residents, and anyone who lacks transportation.

“If the Garcia River rises, that’s when we are extremely affected and can’t go anywhere,” says Linda Lawson, a lifelong Point Arena resident and member of the Manchester-Point Arena band of Pomo Indians. “There’s only one way in and one way out of our reservation.”

When a tree took down a power line on the only street to the reservation during a recent storm, Lawson’s husband and family members were stranded for four days until it was safe to cross again. “Everybody [on the reservation] has their own set of elders or family members that they know to go and check on during a disaster. In the past, when I worked at [the tribal council], we would open up the community center and let people charge their phones and come down for a meal … it was all community-based,” says Lawson.

Apart from getting trapped, the tribe is also worried about water destroying community spaces. “Our roundhouse, which is our traditional area where we do dances and ceremonies, often gets flooded … that’s something that’s very, very important to us,” says Juan Dominguez, another member of the Manchester-Point Arena band of Pomo Indians.

Protecting the “Islands”

When Highway 1 is blocked by landslides or flooding, many communities along the Mendocino coast — especially small, geographically isolated towns like Point Arena — are transformed into “islands.” In the event of a disaster, residents on these islands must be prepared to fend for themselves for days or weeks until help from the county can arrive.

A road gate that cuts off access from the town to Highway 1. Photo: Isabella Eclipse

Dr. Jennifer Kreger, a physician and Mendocino County resident, sees the complexity of needed communication as one of the big challenges to achieving this self-sufficiency. More often than not, community members are willing and able to help each other, but don’t know how until it’s too late. Kreger recounts the story a patient told her of a neighbor hospitalized for three days with congestive heart failure after a five day power outage meant they couldn’t power their CPAP device.

“If I had only known, I could have plugged in their CPAP or even let them sleep in my living room,” Kreger’s patient told her.

People are aware of disasters, Kreger says, but haven’t necessarily thought things through to the next level when it comes to preparing for isolation: “Who are the people I rely on, or who could I go to if I don’t have gas?”

To connect people within and between each “island” Kreger and cartographer Rick Hemmings co-founded the Hubs & Routes project. The project offers an online directory of “Public Hubs” and “Private Hubs” within each community and detailed maps of alternate routes between islands. Public Hubs are businesses, churches or other community centers that can offer at least one free resource during an emergency. Private Hubs are individuals or households who agree to share tools or resources with their neighbors or indicate they might need special help in a disaster. Anyone can access Public Hub information online, while Private Hub information is only visible to designated leaders trained to organize resource exchanges between community members.

Photo: Isabella Eclipse

In Point Arena, registered Public Hubs include the Coast Community Library, Action Network, City Hall, and Point Arena elementary and high schools. The library is currently exploring funding for a backup generator. “The library is a great meeting place for a crisis. It’s a gentle spot that people feel comfortable in — a no-judgment zone,” says Hannum, the town librarian.

Community Gatherings Foster Resilience

Even in a small town like Point Arena where everyone knows each other, there are few occasions where neighbors can sit down and talk about what their evacuation plans are, what resources they have and what resources they might be able to share with others. Low income residents may especially have a difficult time attending such meetings because of work commitments or lack of transportation. So Jennifer Smallwood, founder of Point Arena’s Fire Safe Council, brought her disaster preparedness programs to them instead.

Photo: Jennifer Smallwood

In September 2023, Smallwood organized a community barbeque at the Village Apartments, Point Arena’s dedicated affordable housing. Residents brought their families to eat and received “go-bags” with emergency supplies like a hand crank radio, N-95 masks, rain poncho, and first-aid kit. The bags also came with emergency evacuation tips in both English and Spanish. Most importantly, residents had the chance to share their disaster concerns. Smallwood learned about elderly residents who might need help evacuating and people with pets who wouldn’t evacuate unless they had somewhere to take their animals.

The apartment community responded enthusiastically to the event. “They kept saying, ‘This is so cool. No one’s ever done anything like this before for us,’” says Smallwood. Residents also expressed their fear of being unable to communicate with family and friends in an emergency because of poor cell service in the area. So Smallwood is now working on establishing a network of General Mobile Radio Service (GMRS) radio users in the community and organizing trainings for residents on how to use their radios.

The radios are “good for people who live on one-way-in, one-way-out streets,” explains Smallwood. With the radios, she says, they can tell each other which roads are open, where areas are burned out, or ask how the air quality is in a particular area.

Inspired by a similar program in Sonoma County, Smallwood envisions a network of local GMRS radio users who use repeaters to communicate within the community, while HAM radio operators can help relay news to and from the county’s Emergency Services staff in Ukiah.

And Smallwood isn’t stopping there. With a grant awarded to the Redwood Coast Fire Department by the Community Foundation of Mendocino County, she recently acquired a cargo container to hold blankets and emergency supplies. The container will be parked next to the Point Arena high school, which is both a Public Hub and the official evacuation center for the city. The center is equipped with a generator, air conditioning, wifi, outlets, and even a cafeteria. School buses could be used to evacuate the town in a pinch. The only things missing are volunteers prepared to staff the center. Smallwood hopes to close this gap by holding a training session for community members to become Community Emergency Response Team (CERT) volunteers.

Preparing for Rising Waters

Another area in Point Arena is preparing for a more slow-moving disaster. Point Arena Cove is a small inlet where a creek empties into the Pacific. It’s also a popular hangout for locals and tourists alike, offering a pizza place and seafood restaurant with a deck that’s perfect for watching the sun set over the waves. In the warmer months, the pier is bustling with fishermen cleaning their fish or taking their boats offshore to catch salmon or collect their crab pots. My family loves to take our dogs out to walk on the pier on weekends. They start whining with excitement as soon as they smell the salty, fish-scented air.

When the city planned a seawall and rock revetment project to protect the cove, Arena Cove Stewards, a local nonprofit, pushed for a sea level rise vulnerability assessment instead, gathering 600 signatures from the community in support.

“[People often] don’t think about how building walls and adding rocks makes beaches disappear, increases erosion surrounding the walls or rocks and reduces biodiversity,” explains Billy Arana, founder and president of Arena Cove Stewards.

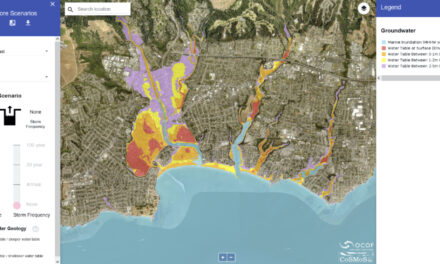

In August 2022, the city of Point Arena received $100,000 from the California Coastal Commission to update their Local Coastal Program (LCP) for sea level rise. One thing that will help lay the groundwork for the update is a draft Sea Level Rise Analysis and Vulnerability Assessment for Point Arena Cove completed by Environmental Science Associates (ESA) in October 2023.

Point Arena’s original LCP did not mention sea level rise at all, although flooding effects in general are already being felt. During the 2023 atmospheric rivers, Arena Cove experienced significant flooding after large waves overtopped the seawall, carrying rubble and debris into the parking lot.

Coastal engineer Louis White of ESA observed the flooding firsthand on Jan. 5, 2023. While on a visit to observe the cove under storm conditions, White became stranded at the hotel in the cove for more than a day. Even though the cove’s restaurants remained above water, other vulnerabilities manifested themselves: With the power out, the pier’s floating dock and boat lift stopped working. The sewer lift station also lost power, so wastewater from the low-lying cove couldn’t be pumped uphill to the treatment plant. Waves almost reached the bottom of the pier.

ESA’s assessment describes how flooding in the cove can be attributed to a combination of marine flooding (tides and storm waves) and fluvial (creek) flooding from Arena Creek. With steep 150-foot-tall bluffs on either side, the small cove channels floodwaters landward. Further upstream, rain can cause the creek to overflow onto and block Port Road, the only road in and out of the cove. The ESA study suggests that flood hazard areas will deepen and move further inland with sea level rise.

December 2023 storms brought high surf to Arena Cove. Video: Chris Sangiovani

On Nov. 30, 2023, the Coastal Conservancy awarded $485,000 to the city for an Arena Cove Harbor Access and Resilience Plan.

The pier, built in 1985, has outlived its 30-year life expectancy and is in dire need of repair, and the Resilience Plan will help Point Arena redesign the pier and harbor to be resilient to storms and sea level rise.

Arena Cove Stewards is poised to help with the community outreach part of the planning process. “The challenge will be for people to realize that adapting doesn’t mean giving up, but that it provides us with an opportunity to correct the mistakes of the past and make a better, more sustainable future,” says Arana.

The Road Ahead

As I write this article, Point Arena is currently experiencing an early winter deluge of rain. This time around, my family is prepared with a generator, flashlights, firewood and a week’s worth of canned food. More importantly, we know where in town we can go to stay warm, make phone calls, and find help from our neighbors.

There is still far to go in order to create a truly resilient Point Arena, especially considering our remoteness and lack of outside support, but residents have already shown they can beat the odds. Connecting with our community and sharing resources and knowledge is one way to turn our town’s small size into an asset rather than a disadvantage. By taking matters into our own hands and reaching out to our most vulnerable neighbors, we can empower our town to weather the storms ahead.

EXTREMES-IN-3D

SERIES CREDITS

Managing Editor: Ariel Rubissow Okamoto

Web Story Design: Vanessa Lee, Tony Hale, Afsoon Razavi

Science advisors: Alexander Gershunov, Patrick Barnard, Richelle Tanner

Series supported by the CO2 Foundation.

Reporting supported by Pulitzer Center, Connected Coastlines.

Special Credits for Isolated Town Story

Top Photo: Late afternoon traffic in Point Arena by Scott Sewell

Map: Darren Campeau

Developmental Editing: Kim Hickok

Special thanks to Donne Brownsey, recently a public member of the California Coastal Commission