In Atlas of Disaster, No One is Safe

Downtown Monte Rio, during 2019 storm events similar to those the Bay Area is experiencing this year. The adjacent Russian River is one of the most flood-prone rivers in California. Photo: Jak Wonderly.

Considering the present and probable future miseries of climate change, it’s tempting to take a certain comfort from the problems of Elsewhere. “At least we don’t have to worry about sea level rise,” inland dwellers may say. “At least we don’t have to worry about water supply,” Easterners may think. “Anyway we don’t have hurricanes,” Californians may imagine.

“We don’t have that many heat waves,” New Englanders may remark. And a Nevadan might point out that the state ranks last among 50 in the number of federally declared disasters it has endured.

Experience is teaching us, though, that the global warming banquet has a dish for just about everyone. That dawning intuition is backed up in detail by a recent report called The Atlas of Disaster.

The Atlas is the latest product of Rebuild by Design, a public-private partnership that grew out of the trauma of Superstorm Sandy in 2012. After focusing on ideas for the New York metropolitan region, it widened its field first to 11 states and then to the nation.

Pulling together data from many sources, the Atlas finds that 90% of U.S. counties have had an extreme weather event in the last ten years, with over 300 million Americans affected. The authors call attention especially to “the deadliest risk,” the scourge of excessive heat. Though heat waves don’t rate federal disaster designations, they still cause plenty of suffering and economic damage. In this regard, Nevada no longer looks like such a safe haven: it has the highest reported rate of heat-related deaths in the United States, closely followed by Arizona. Heat’s companion, drought, also gets its own chapter in the Atlas as an underrated hazard.

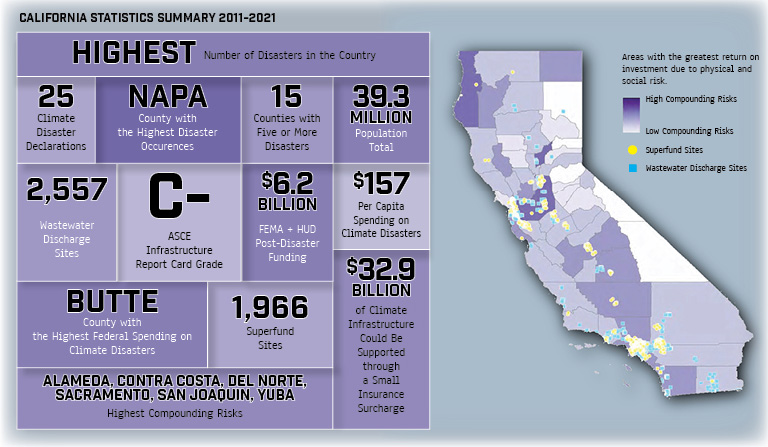

California findings from Atlas of Disaster.

The heart of the Atlas report is its state-by-state assessments. Each state’s section includes four maps showing disaster declarations, FEMA payouts, energy reliability, and “social vulnerability,” a rating based on analysis by the Centers for Disease Control. The final map in each array is titled “compounding risks.”

Overlaying different stressors, it identifies counties where preventive investment would yield the most bang for the buck. In California, a standout swathe of high-risk territory might be called the San Francisco Estuary block; it includes Alameda, Contra Costa, San Joaquin and Sacramento counties. Yuba and Del Norte counties also rank conspicuously high.

“The current process by which federal disasters are declared — and money allocated — represents a time when climate disasters were anomalies,” write the authors of the Atlas. “This is no longer the case.”

It can be cost-effective to shift dollars from disaster response to disaster preparation, but making the switch is hard. Prevention, if cheaper than cure, is still head-spinningly costly; even the infrastructure money released by the just-concluded Congress comes nowhere near meeting the need.

The authors of the Atlas have a solution to offer. Each state, they counsel, should create a Resilient Infrastructure Fund, to be supported in most cases by a 2% charge on premiums for property and casualty insurance. By this means, California could raise over $3 billion a year for preventive measures.

When something similar was proposed in the state of Washington, the insurance industry fought it off. But Rebuild by Design thinks that insurers, needing to take the edge off future climate payouts, will come around. “The companies almost have to do something to save themselves,” says Rebuild’s Johanna Lawton.

I ran the 2% idea past insurance expert Kathy Schaefer, formerly of FEMA, now a gadfly scholar seeking new ways to fund prevention and get more people insured. Though glad to see new ideas emerging, she thinks this one needs work. “Low-income communities are already overburdened by insurance,” she says. “Adding 2% is a non-starter.”

Yet Schaefer is exploring a kindred idea. One thing that premiums reflect is insufficient information about risk; uncertainty itself produces a sort of surcharge. Some companies seem open to earmarking a portion of each premium for better risk mapping and assessment — shifting funds towards disaster prevention efforts without raising rates. Better data should ultimately lead to lower outlays for companies and policy-holders alike.

New funding ideas can’t come too quickly for California. The rainy winter of 2023 reawakened our drought-accustomed brains to the hazards of too much of a good thing. And, for all it says about the universality of risk, the Atlas of Disaster confirms that California, with 25 federally declared disasters between 2011 and 2021, still ranks first on that list.