How Far Can Metro Harbors Go on Nature-Based Shore Protection?

Manhattan, Miami and San Francisco are all facing off with the ocean as it advances on their urban footprints. Photo: by Mario Bruns, Unsplash.

When Hurricane Sandy hit New York City a decade ago, powerful winds pushed the water in the harbor 14 feet higher. This storm surge crested seawalls and flooded parts of the city to depths of nine feet. Dozens of people drowned, and water poured into subways, tunnels and the homes of more than 443,000 people. Economic damages were estimated at $19 billion. Now, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has a plan to keep disasters like this from happening again.

Across the country, San Franciscans watched news footage of the destruction from Sandy and were horrified at the thought of something similar happening here. Storm surges are much smaller in California than on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. But much of the Bay Area is built on fill and former marshes, and these low-lying areas are increasingly vulnerable to flooding as storms intensify and sea levels rise.

Typical flood protections rely on engineered structures like seawalls and levees. But now there’s a new push at the national level to prioritize working with nature. Examples include restoring floodplains and wetlands, which dampen waves and also provide ecosystem services from carbon sequestration to water purification.

Implementation of natural solutions is uneven at the local level, however, and storm surge plans currently underway in New York, Miami and San Francisco highlight a range of nature-based fixes from business-as-usual to out-of-the-box.

A Traditional Approach in New York

At the traditional end of this range is the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers plan for New York, the Harbor and Tributaries Study, which uses a mix of barriers along shorelines and across waterways as the primary defense. The barriers on rivers and streams, which would be equipped with gates that close during storms, are particularly concerning, says Tracy Brown, president of the environmental nonprofit Hudson Riverkeeper.

“The barriers are permanently in the water and go all the way across,” Brown says. “They would impede the flow of water and of fish.” Tidal waters flow up and down the Hudson River along half of its 315-mile length and many species, including the endangered Atlantic and shortnose sturgeon, move with these flows.

Installation of a floodwall in the East Side Coastal Resiliency Project in July 2022, part of a 2.4-mile flood barrier of berms, floodwalls, moveable gates and raised parkland that will protect 110,000 East Side residents. Photo courtesy NYC Department of Design and Construction.

Alternatives include sea gates that are built on land rather than into the water and retract completely when not in use, allowing waterways and aquatic wildlife to move freely. That said, land-based gates could still harm ecosystems. The gates are meant to be used infrequently — just to block catastrophic storm surges — but Brown fears they could also end up being deployed for increased flooding due to the rising seas and heavier rains driven by climate change.

“There would be pressure to close the gates more and more,” she says. “They could be misused.”

Another possibility Brown hopes to see on the table is strategic retreat. Many people in flood-prone communities are low income and often unable to relocate in New York City’s pricey housing market. Brown envisions creating equity by offering these residents new affordable housing built safely above floodplains.

Brown also urges officials from the mayor to the governor of New York to partner with the Corps on expanding the range of protections under consideration. “Local leadership could step in and co-lead on this problem,” she says. The Corps has a longstanding provision for this course of action, which is known as a locally-preferred plan.

Not-so-nature-based flood protection in Miami. Photo: Marc Bluhm, I-Stock.

Back to the Drawing Board in Miami

In 2021 officials asked for a locally-preferred plan in Miami, which has faced storm surges as high as 15 feet, and the Corps has now re-initiated the planning process. “We’re constantly aware that our coast could flood,” says James Murley, Miami-Dade County’s chief resilience officer and lead on working with the Corps on the storm surge plan.

While the Corps plan did include natural approaches like mangrove and marsh restoration, it also proposed lift gates in the mouths of drainage canals that propel floodwaters inland during hurricanes. Not only are lift gates untested in this setting, but they would be flanked by towering seawalls designed to shield the coast from floodwater that bounces off the gates.

“That was the stumbling block for us,” Murley says, describing the seawalls as slabs of cement one hundred feet off the shoreline that go straight up in the air. “We wanted other benefits like more habitat — we’re in the first year of the restart and that’s what we’re going to explore.”

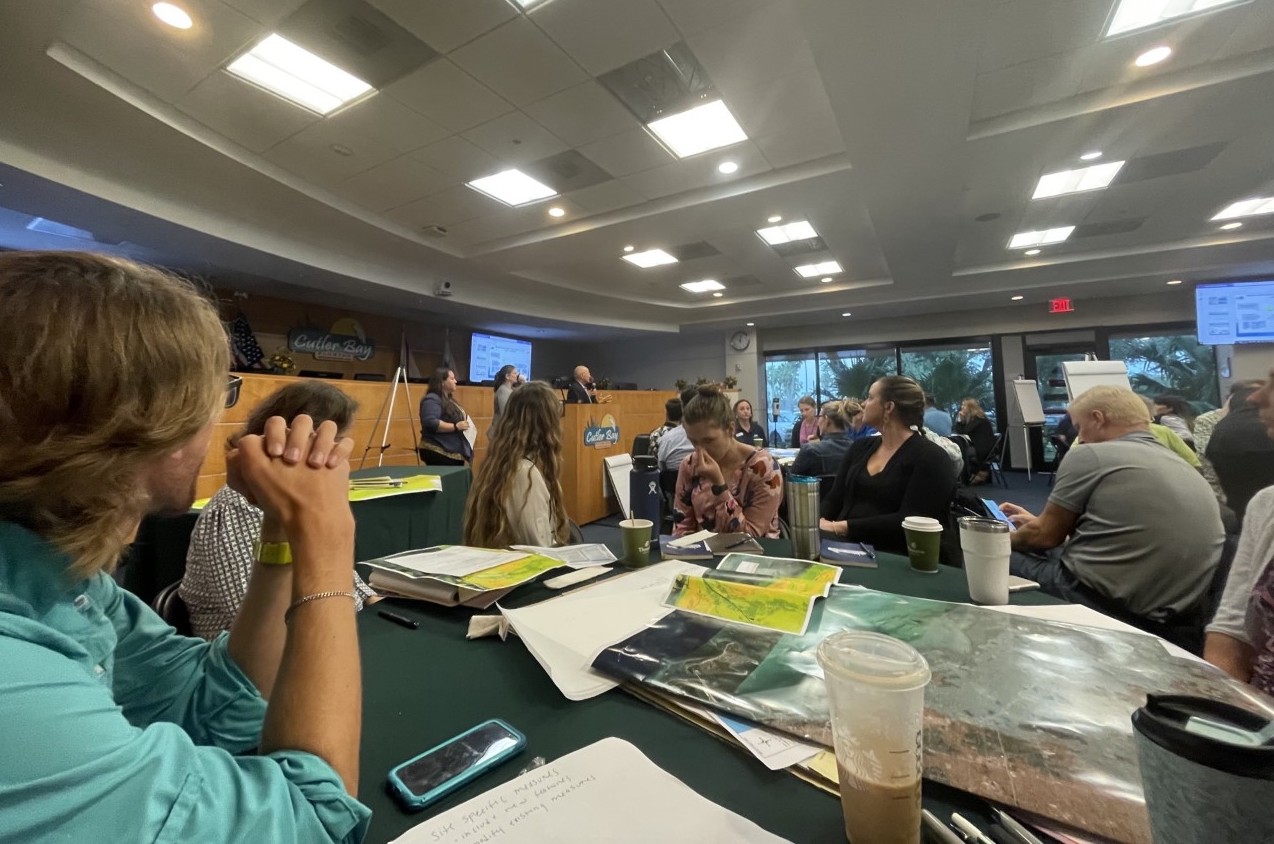

Key stakeholders including natural resource managers, government staff, landscape architects, academics, Army Corps staff, and local consultants work together at a charrette to identify more natural and nature-based solutions for the Back Bay Study. Photo: Miami-Dade County.

Murley also understands the perspective of the Corps, explaining that the agency is charged with offering the greatest level of protection for the highest return on investment. The effort is collaborative on both sides. “We all want to make this work,” he says. “We’re very interested in a solution because the Corps is our lifeline to Congress, which is the big bank in the sky.” Under the locally-preferred plan, the Corps will foot 65% of the bill.

In cases where local officials and the Corps do not reach agreement on a plan, projects can proceed under full local control. This process, called deauthorization, requires an Act of Congress. In the Bay Area, the Contra Costa County Flood Control District recently deauthorized the lower part of Walnut Creek to facilitate moving forward with its vision of flood protection that also includes tidal marsh restoration and public access.

Engineering with Nature in San Francisco

The Corps has built-in barriers to working with nature. Notably, the cost-benefit analyses intended to give the biggest bang for the taxpayer buck are outdated, for example accounting for property damage avoided but not ecosystem services gained.

The Biden Administration wants to remedy this. In November 2022, the White House announced a Nature-Based Solutions Roadmap to help make working with nature a “go-to option.” This program includes putting numbers on the economic benefits of doing so, in hopes of making it easier for the Corps and other government agencies to justify investing in ecosystems.

The Corps has 38 geographic districts under the umbrella of a national headquarters. At the top level, the Corps has long had an Engineering with Nature Initiative geared toward working with natural processes. This philosophy has been slow to filter down to the district level, however. Sso the Corps recently designated seven districts, including the San Francisco district, as Engineering with Nature proving grounds for testing innovative ways of integrating environmental considerations.

“It’s giving people the courage and technical know-how to think differently,” says Julie Beagle, a former San Francisco Estuary Institute climate adaptation expert who now leads environmental planning for the Corps’ San Francisco district.

To Beagle, at least a little bit of nature can be integrated into any engineering project. Her team is scouring the planet for forward-thinking designs that could work along the seven-mile San Francisco waterfront. “It’s a super urban, deep-water port built on fill,” she says. “Parts of it flood during king tides.”

The Port of San Francisco’s Heron’s Head project constructed a gravel beach to protect a restored marsh from erosion, completing work in late 2022. This tiny urban marsh supports shorebirds and federally-protected species, and provides waterfront access and open space to communities in nearby Hunter’s Point. Photo: Port of San Francisco.

Promising finds include canals in London with living benches that offer refuge to fish. “They don’t just experience the smooth bulkhead wall, they have places to eat and hide,” Beagle says. Similarly, Australia has living seawalls that are textured. These structures are full of nooks and crannies for marine life, and also help attenuate waves. The Port of San Francisco is piloting living seawalls at three sites, starting with one near the Ferry Building.

“There’s always something you can do,” Beagle says. “It’s not an either-or.”

This story is one of Three Tales of Trouble and Triumph in the East Coast Fight Against Storm Surge.