High-Concept Plans for a High-Risk Shoreline

“We don’t want to have a fortress to protect us from sea level rise.”

Four creeks, two lagoons, and untold numbers of high-flying birds are creating challenges for an ambitious effort to protect a valuable — and vulnerable — stretch of shoreline near San Francisco International Airport from climate-related flooding.

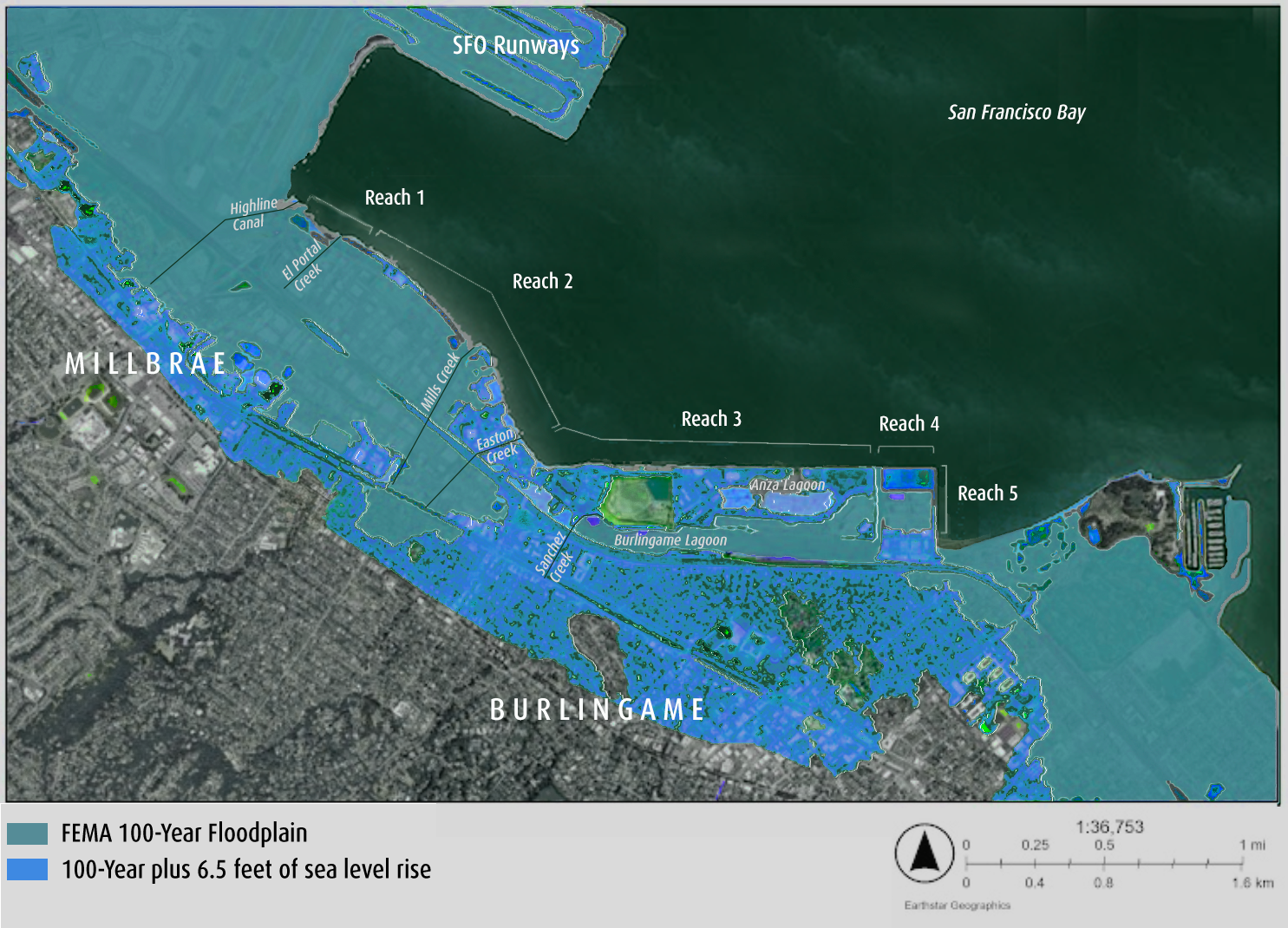

The area is both low-lying and densely developed, with an estimated $2.4 billion in property at risk, as well as important regional infrastructure including parks, two water treatment plants, electrical distribution facilities, a rail corridor, and a section of Highway 101. Many of the properties in the area and beyond are within FEMA’s 100-year floodplain, and sea level rise is expected to significantly expand the vulnerable area.

The Millbrae and Burlingame Shoreline Resilience Project, led by OneShoreline (aka the San Mateo County Flood and Sea Level Rise Resiliency District) seeks to protect slightly more than three miles of heavily urbanized waterfront while improving public access to the Bay and wildlife habitat.

The project stretches from just south of SFO, where it ties into and leverages the airport’s own shoreline resilience program, to Burlingame’s border with the City of San Mateo. It is punctuated by six gaps — four creeks and two lagoons — which create a major design challenge.

“We are looking to elevate the entire shoreline to at least 16 feet [five to six feet higher than its current level],” OneShoreline’s Makena Wong explained during a webinar held last fall as part of a series of public outreach events, “but the creeks and lagoons need to remain open so they can drain to the Bay when rain falls. And when there are high tides and sea level rise, we need to keep that water from going up the creeks and lagoons and flooding adjacent properties.”

Flood risk to the project area, which is divided into 5 reaches for planning purposes, along the Millbrae-Burlingame bayshore. “100-year” floods are becoming more frequent with climate change. Maps: OneShoreline

Last fall’s community events focused on three draft alternatives that tackle the creek dilemma in different ways. All three involve enormous amounts of new infrastructure and some amount of Bay fill.

The first alternative would require the least amount of Bay fill — approximately 70 acres — and would manage water around the creeks with pump stations and tide gates at each creek mouth. Although this approach involves the fewest changes to the shoreline, it requires the most pump stations, which are expensive and energy intensive to operate. As sea levels rise and extreme storms become more frequent, the expectation is that the pumps would need to run more often and for longer periods.

The second alternative was inspired by San Francisco’s Tunnel Tops park. In this scenario, underground tunnels would transport water from the creeks to one large pump station. A new park atop the tunnels would significantly increase shoreline green space. Engineers warn, however, that building the tunnels through Bay mud, and then maintaining them, would be very complicated.

The third alternative would create a 200-foot-wide nearshore waterway with a combination of levees and seawalls. Tide gates and pump stations would control water levels in the waterway and a new reach of Bay Trail would run along the top of the levee. Although this alternative would allow water to pass in and out of Highline Canal and El Portal Creek without pumping, it would affect Bay views and access, and the water quality impacts are not clear.

Current trail along shore. Photo: OneShoreline

All the alternatives would also widen some parts of the Bay Trail from six feet to 20 feet, and close nearly a mile’s worth of current gaps in the trail. They also all feature a sloped, living shoreline that would allow marsh and other habitat to migrate landward as sea levels rise, at least where feasible.

“We don’t want to have a fortress to protect us from sea level rise,” says Wong. “We need to have higher elevation, but want to do that in a gradual, softer way. A gradual slope also means we don’t have to build as high.” An intervention involving a more abrupt elevation change, such as a seawall, could require building as high as 20 feet in some areas. The tradeoff is that a more gradual slope means placing fill further out into the Bay.

According to Wong, nearshore improvements might include reefs, providing places for oysters and other invertebrates to attach, as well as habitat for fish. The nearshore reefs might also encourage sediment to accumulate and coarse beaches to form, providing more natural flood protection.

Favored fishing spot and current shoreline protection (riprap). Photo: OneShoreline

Although facilitating healthy ecosystems along the shoreline is one of the stated goals of the project, establishing new habitat so near the airport creates a major challenge. For the safety of the flying public, it is essential not to increase habitat that attracts high-flying birds, such as pelicans and seagulls, to the area. According to SFO’s Doug Yakel, the airport has communicated design considerations that reduce the risk of bird hazards to OneShoreline. “We are confident these considerations are understood and will be incorporated into the ultimate project plans to secure our shared shorelines,” he says.

In the coming months OneShoreline will analyze community feedback on the alternatives and refine them before selecting a preferred alternative this summer. It is very likely that the final design will be a hybrid of two or more of the alternatives, according to OneShoreline CEO Len Materman, while private development will also be part of the puzzle.

Project planning is closely connected to the implementation of a zoning ordinance, adopted by the City of Burlingame with the help of OneShoreline two years ago, that includes a regional first: guidance on sea level rise resilience measures that new development must implement.

“There are new development agreements in Burlingame that require the developer to include shoreline protection and provide an easement for OneShoreline and/or the city to adapt that infrastructure if needed,” says Materman. For example, one project that has already received city approval encompasses roughly a kilometer of shoreline right in the middle of the OneShoreline project area and includes a levee, setbacks, a trail system, and open space.

“We are encouraging developers to work with us,” says Materman. The more developers include FEMA-accredited infrastructure in their proposals, he notes, the lower the cost of OneShoreline’s eventual project.

Mouth of Mills Creek, a two-way flooding design challenge for the project. Photo: Cariad Hayes Thronson

The final design will need to be approved by both city councils, and OneShoreline has worked closely with the cities on the alternatives. “We are really concerned about flooding and shoreline protection, and also drainage from the city into the Bay,” says Millbrae’s director of public works Sam Bautista, who has participated in the project alongside his Burlingame counterpart. Other community concerns focus on impacts to views and recreational opportunities. “We’ve had lots of interaction with the cities,” says Materman. “We’ve heard what their concerns are, and that has helped educate us about what alternatives we should be moving forward with.”

At this stage it is too early to estimate how much the project will ultimately cost, although “a lot” seems like a reasonable guess. So far the project has been funded by a $8 million state grant obtained with the help of then-Assemblyman Kevin Mullin. “That money will get us through a draft EIR and to a level of design where we could start working on permit applications,” says Materman.

Given the Trump administration’s hostility toward any kind of climate-related activity, federal funding is unlikely for the foreseeable future. Nevertheless, Materman is optimistic about the project’s prospects.

“We have state and local governments that are committed to looking ahead and solving these [climate-related] problems,” he says.

Shore walk in November 2024 to show members of the community the lay of the land and project area. Photo: Cariad Hayes Thronson

Materman believes the Millbrae-Burlingame project can provide a valuable model both for other areas near airports and multi-jurisdictional projects in general.

“Oakland’s airport is also right on the Bay, and there are several other regional airports alongside it, so all of us are going to have to be thinking about how shoreline protection works with their unique constraints,” he says.

More broadly, he believes the project can provide lessons for other parts of the Bay Area where water is the defining boundary between cities.

“Aligning protection for multiple jurisdictions is really important and really hard to do, especially when there’s a creek that divides the two cities. We need, as a region, to figure out the best ways to address that reality,” says Materman.

Although several plans and programs, including the new Regional Shoreline Adaptation Plan from the Bay Conservation and Development Commission, call for regional planning, Materman says the Millbrae-Burlingame project is different.

“I can’t think of another project that involves multiple cities along the shoreline that is tackling this many difficult issues on the ground right now,” he says. ”It’s relatively easy for one jurisdiction to do high-level planning, even to build climate resilience. But it gets much harder when multiple jurisdictions are working together to address multiple complex challenges — some of which conflict — at the same time during the design and permitting phase. Going through this is required for this part of San Mateo County, and I’m confident it will help the other areas of the Bay that will be confronting this soon.”