Slow Progress on Shade For California’s Hottest Desert Towns

Communities in California’s inland valleys and small unincorporated towns face record temperatures with little shade. Policy changes lag as local groups push for heat equity.

On an 80-degree day in February, a dozen desert residents gather in Coachella, California, to discuss heat issues as part of the state’s fifth Climate Change Assessment. To start, they say a few words each associates with the rising temperatures they’re experiencing more frequently and intensely every year: “Too much.” “Irritating.” “Hell.” Two people say “Stressful.”

Because of the timing of the meeting, one woman eventually asks “Is this still winter?”

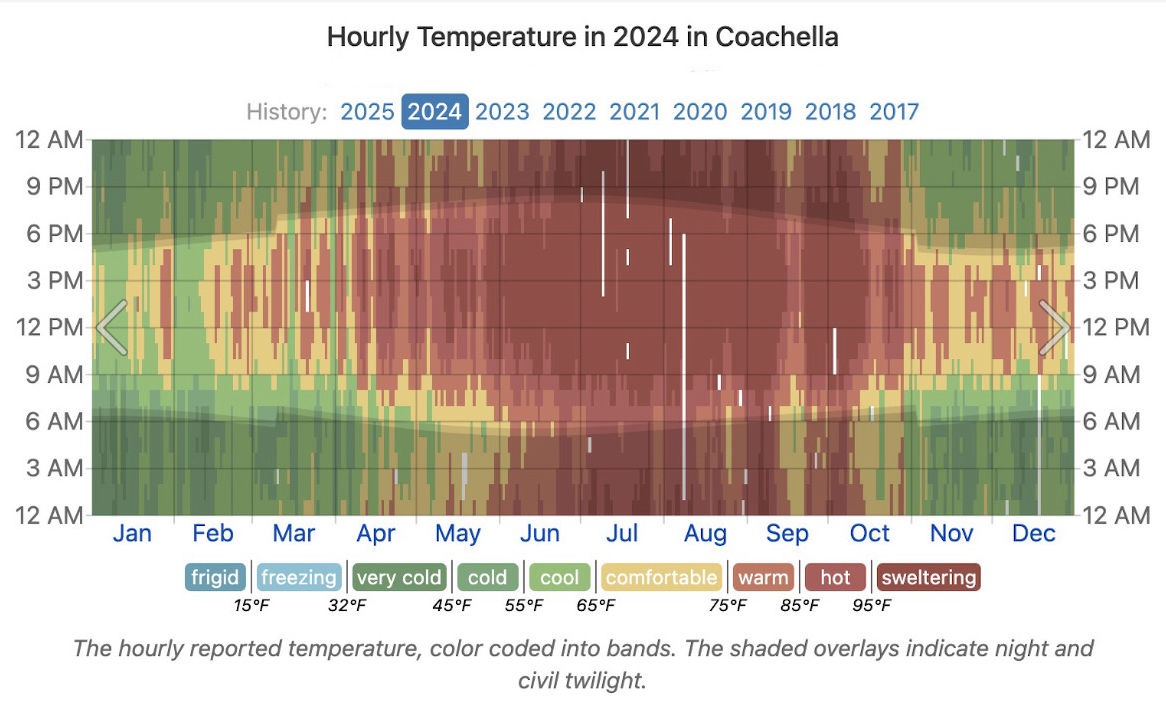

While the Coachella Valley does get cooler winter days, extreme heat now pops up year-round and seems to hit even harder in the summer.

In July 2024, Palm Springs had its highest recorded temperature ever at 124 degrees. The previous all-time high in that valley city occurred in June 2021, at 123 degrees.

And this March, Palm Springs had a 100-degree day, breaking its 1988 record of 97. At the same time, in the eastern part of the valley, the unincorporated town of Thermal reached 101 degrees, while the city of Indio sweltered at 102 degrees — both also breaking 1988 records.

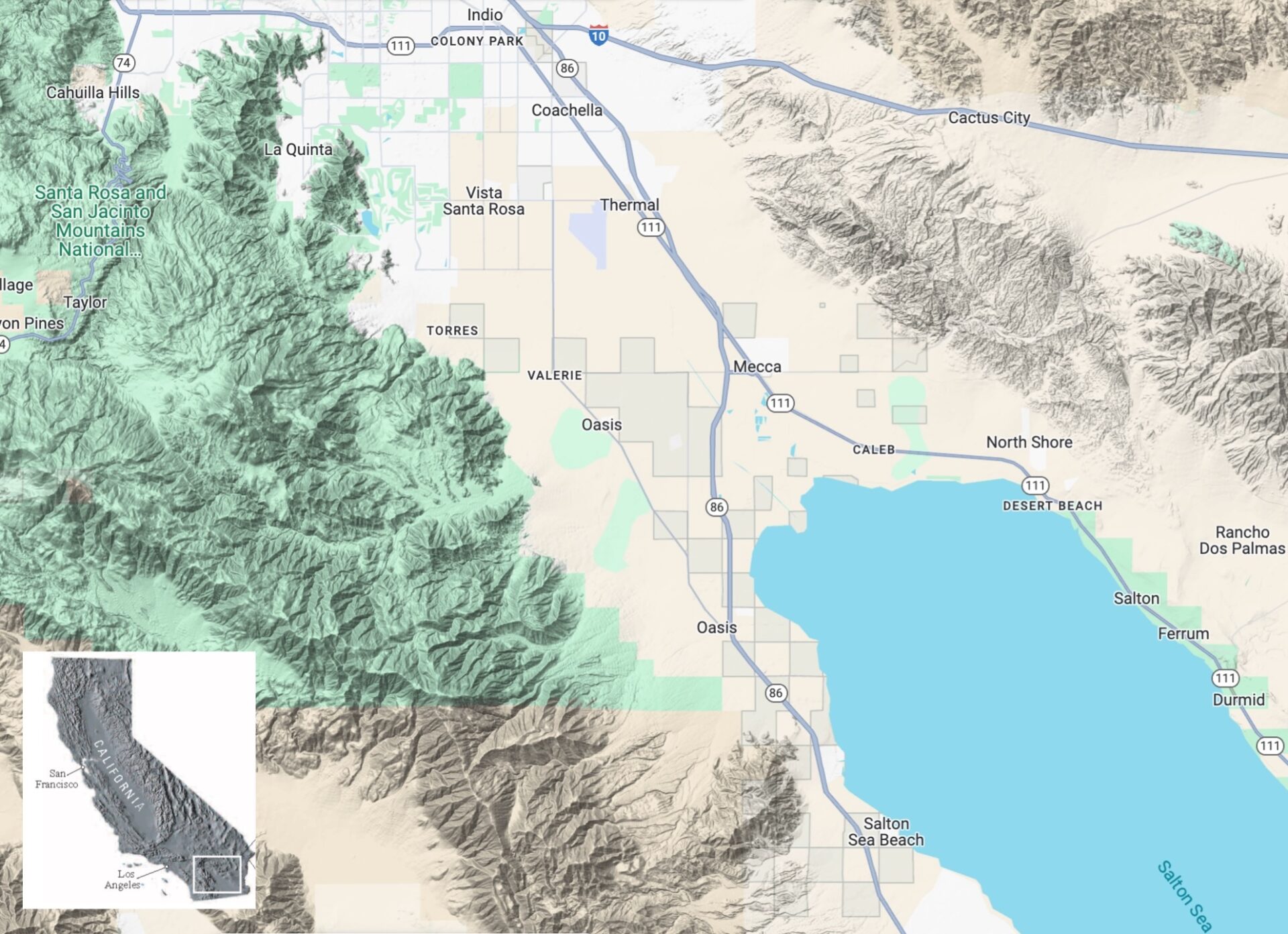

The increasing heat in the Coachella Valley has prompted several studies and initiatives in the region, particularly in towns with lower-income residents, who have less access to green spaces and shade, as reported in KneeDeep Times in 2023. These towns also have less public infrastructure, such as libraries and transportation hubs, that could offer some relief.

Alianza offices on the night of the February meeting. Photo: Eliana Perez.

The February 2025 gathering, hosted in the local offices of the nonprofit Alianza Coachella Valley and conducted by a trio of researchers with the University of California Riverside, adds to those efforts.

Though the state’s climate change assessment — done every three years — targets different California regions, the inland desert region is “unique, socially and geographically,” says Ryan Sendejas, who works at UCR’s Environmental Science Department and is an author of the study.

“The eastern part of Riverside County [and] Imperial County have some of the worst air quality in the country on peak days, for sure,” Sendejas says. “As it’s getting hotter out there, it’s becoming more arid.” Aridity can exacerbate problems with pollution, he explains.

“The Salton Sea is just a major environmental disaster, sitting there waiting to happen,” he says.

When the Salton Sea — California’s largest lake — is running dry, it’s easier for desert winds to blow dust, salt, and harmful chemicals from the exposed lakebed into local communities.

Wind stirs up dust on the Salton Sea. Photo courtesy Ryan Sendejas

Despite the assessment’s aim at overall environmental changes, Sendejas says the discussion in Coachella revolved around heat because desert residents better understand its impact than those on the outside.

“With heat, people don’t really see it as an environmental disaster. They just see it as something that individuals have to cope with on their own,” he says. “When people think of lives lost [due to climate change], everyone would probably go to fires or flooding, but the reality is, more lives are lost due to heat-related issues than all those other things.”

Data from the California Integrated Vital Records System shows that the Coachella Valley typically has far more heat-related deaths than any other part of Riverside County.

While locals are the ones living with extreme heat and other changes, Sendejas says this is the first time that dialogue with the community forms part of the state’s assessment.

Source: Weather Sparks

Living With Extreme Heat

The twelve residents that participated in the assessment meeting in Coachella were not the only ones interested in the matter, but there was a cap on the number of attendees to allow time for everyone to speak.

Ages ranged from young adults to seniors and the group was almost equally divided in men and women.

Attendees were from all over the eastern Coachella Valley and farther out, from Salton City in Imperial Valley.

They shared symptoms they’ve experienced on high-heat days, like nosebleeds, vomiting, and mental health struggles due to having to stay cooped up inside the house. They also touched on their concerns for those they think are most affected by rising temperatures: farmworkers, gardeners, unhoused people, and school kids, among others.

“They’re out at recess and the playground is hot, the asphalt is hot. Then they’re waiting for the bus and there’s no shade to cover them. When they’re on the bus, there’s no air conditioning. It’s no wonder they get home irritated or feeling sick,” Juana Garcia Ramirez, 53, says in Spanish about her grandchildren.

A bus stop in Thermal. Photo: Maria Sestito

Slogging Toward a Master Plan

For about four years now, the Luskin Center for Innovation at the University of California Los Angeles has been working alongside community development nonprofit Kounkuey Design Initiative on a study of the impact of heat issues in the area’s unincorporated towns.

For Lana Zimmerman, project manager of heat equity research at the Luskin Center, that has meant reviewing building codes, state and county laws, and “things that are even more micro,” she says. “I’ve divided my framework of research by exposure settings. So, I looked at mobile homes, public schools, public parks, transportation, and agriculture. Those are the five main areas that I’ve been looking into expanding shade cover in.”

Map of Coachella Valley.

She emphasizes the center’s partnership with KDI, which has facilitated community engagement, specifically by working with the Oasis Leadership Committee, made up of 16 local residents, to find the best shade opportunities.

In 2022, these partnerships and conversations produced a colorful wooden bench and shade structure, placed at a bus stop in Oasis after the study found a need for shade throughout the town’s bus route.

Though the hope is to keep offering solutions like the shade structure with the conclusion of the study, Zimmerman says finding funding to implement the resulting shade plan will be difficult. In the coming months, she’ll be working to identify different funding channels to get shade added, examining existing and proposed heat policies to build on, and finetuning the “precision of our plan, to marry community engagement, spatial analysis, and policy research.”

Set to finalize this June, the plan may be delayed further after recent staff changes and other adjustments, according to Zimmerman. “We could take even longer than we had scoped, but obviously we have to get something done at some point,” she says.

A Center for Climate Resiliency

As the study for a shade master plan continues, the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability, another local nonprofit, is also helping in lessening the impact of climate change in the eastern Coachella Valley, specifically in the towns of Mecca and North Shore.

After receiving a grant for $4 million from the state’s Transformative Climate Communities Program, Riverside County decided to prioritize the two unincorporated towns due to their lack of basic infrastructure, such as roads, says Krystal Otworth, senior policy advocate with the Leadership Counsel.

The grant will also fund bridge improvements along Avenue 70, solar roof assessments, and free roof repairs for local homes, plus the development of a community center with year-round programming that can also offer a clean and cool air refuge during extreme weather.

“The [proposed] Climate Resiliency Center really came about because the community of North Shore is the closest to the Salton Sea and there is not a lot of street infrastructure, so that community in particular is very susceptible to high wind events that lead to poor air quality. In general, there’s also not a lot of foliage, so there is a lot of extreme heat that happens there as well,” Otworth explains.

To engage the community in all these projects, the Leadership Counsel announced the creation of a Mecca-North Shore Climate Resiliency Project Committee. The committee will consist of five agency representatives and six residents of Mecca and North Shore.

Otworth says the members will be chosen by a public voting process, and the resulting committee will guide and oversee the projects to completion. Community members will be paid to participate in the committee.

As all these groups, organizations, and institutions work to address extreme heat and build climate resiliency in the Coachella Valley, Sendejas says he’s open to seeing more partnerships established, though that is not his call within the California Climate Resiliency Assessment.

“When we are looking at creating solutions, they need to be intersectional and dynamic. They need to be fluid as well. We need to be able to pivot our position when things change and we also need to be equitable within society,” he says.

As part of the assessment this year, Sendejas designed and presented an interactive map to the residents that gathered in Coachella. Within the map, people are able to pin parts of the desert and write out a blurb that describes the impact of climate change there.

Results from community survey of places where health impacts from heat are felt (red points) and places with resiliency opportunities (green points). Survey: UC Riverside/CCRA

After more meetings across the state’s inland desert regions, Sendejas and his colleagues plan to present this and all other research to state and local governments.

”There is a vision that I have in my mind to develop resiliency, not only within the environment but within society and people as a whole. And in order to do that, we need to have diverse perspectives, backed by the science that we do know,” he says. ”And so, my end-goal would be having [a] framework that fosters that for the climate change assessment.”

Top: Ryan Sendejas (center) presents information about extreme heat in the Coachella Valley to local residents as part of California’s fifth Climate Change Assessment in Coachella, California, on Feb. 18, 2025. Photo: Eliana Perez

![]() The story is a follow up to another in KneeDeep’s Extremes-In-3D series.

The story is a follow up to another in KneeDeep’s Extremes-In-3D series.

Series funded by the CO2 Foundation.