Getting Serious at the City & County Scale About Future Flood Threats

BCDC releases minimum standards and guidelines for cities and counties crafting plans to reduce shoreline flooding, but will they mesh across the region?

Sea level rise, now teasing us with a just-perceptible creep, is expected to pick up speed soon. The same can be said of California’s efforts to deal with rising tides. After two decades of earnest but disconnected or toothless studies and plans, a new state mandate is concentrating minds.

Last November, the Governor signed SB 272, titled “Sea Level Rise: Planning and Adaptation.” Pushing beyond urgings and encouragements, the law now commands local governments to write plans for encroaching waters; moreover, it puts specific state agencies in ultimate charge. Along the ocean coast, the umpire is the California Coastal Commission. Around San Francisco Bay, it is to be the Bay Conservation and Development Commission. Until now, BCDC had authority only over tidelands and a 100-foot mainland band. Now it has a voice in a much wider bayside zone.

BCDC has been alert to sea level rise since 2005, when then executive director Will Travis read a prescient series of New Yorker articles by Elizabeth Kolbert and started wheels turning. Since then, the agency has done much by way of research and education, in several phases. Adapting to Rising Tides begat Bay Adapt begat One Bay Vision. Now comes something different: the translation of data and aspirations into specific plans and projects at the level where most land-use decisions are made. These local plans are due by the end of 2033. And, yes, BCDC can turn them down.

On September 16, as instructed by the law, BCDC published draft guidelines for local planners (and other “practitioners”). These are embedded in what the agency calls its Regional Shoreline Adaptation Plan, or RSAP. That title is a promissory note, for the real plan will be the sum of local, or “subregional,” blueprints still to come. The RSAP in its present form is a sort of instruction manual for building a communal ark. That manual runs to 200 pages, but the heart of it all is in four Minimum Standards that cities and counties are to meet as they plan.

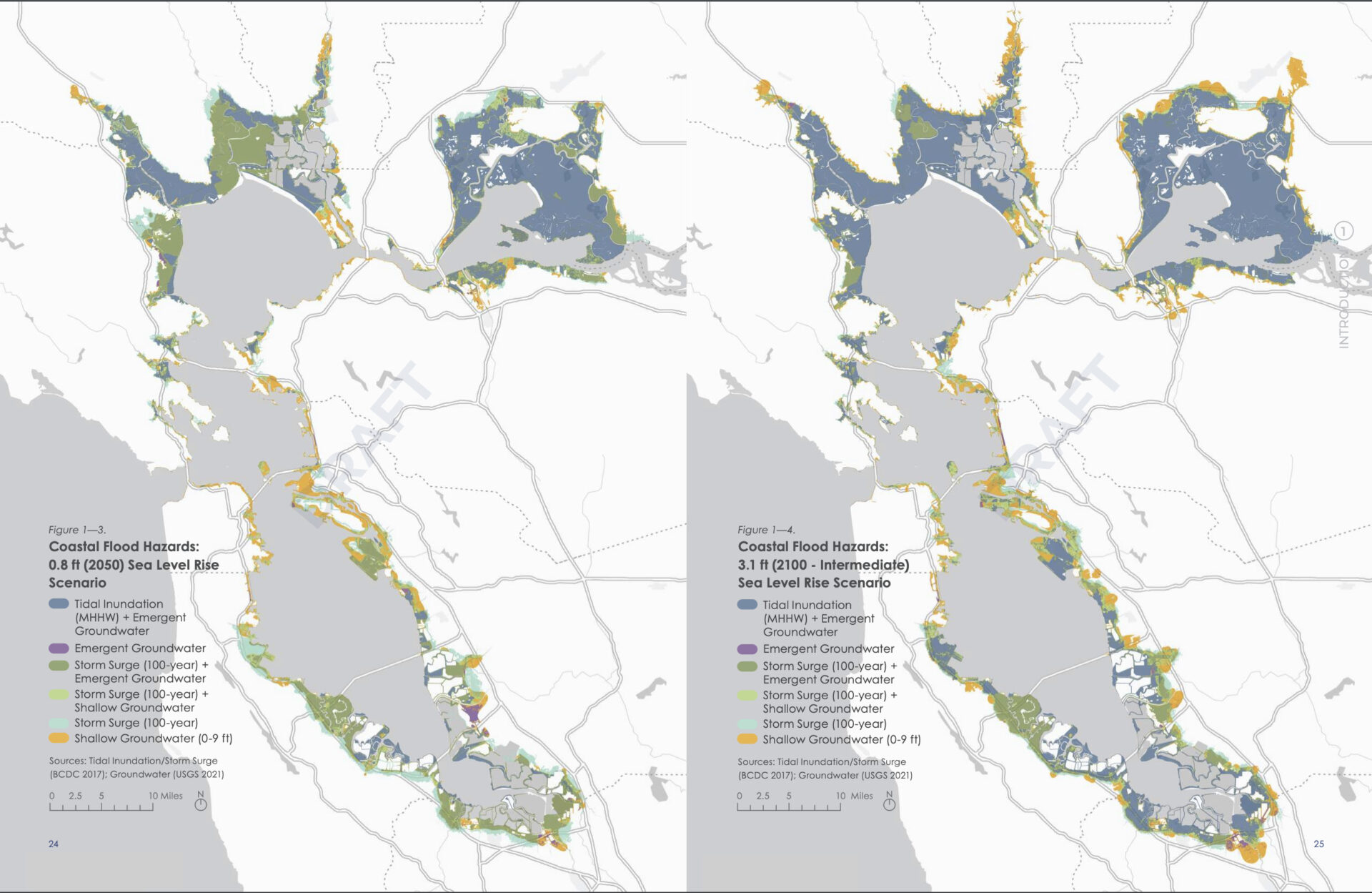

The first Standard lays out the water levels that must be planned for — that is, the projections that are to be followed. Everybody is to assume an 0.8-foot rise by 2050, and brace for a 3.1-foot rise by 2100. That’s the “intermediate” level in a range of longer-range projections by California’s Ocean Protection Council. The planning area, however, must include all territory threatened by a 6.6-foot rise — OPC’s high projection for 2100 — and at least some thought must be given to responding to that level. Numbers are also specified for other hydrological aggressions: storm surge (when strong onshore winds make high tides higher), and rising or surfacing groundwater. The groundwater piece is newly prominent. “Its inclusion will change the plans,” says Kristina Hill of the UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design, an RSAP advisor.

The second Standard is called Minimum Categories and Assets. It lists over 70 interests and factors that must not be overlooked if present, from eelgrass to police stations, and includes “growth geographies” and “housing opportunity sites.”

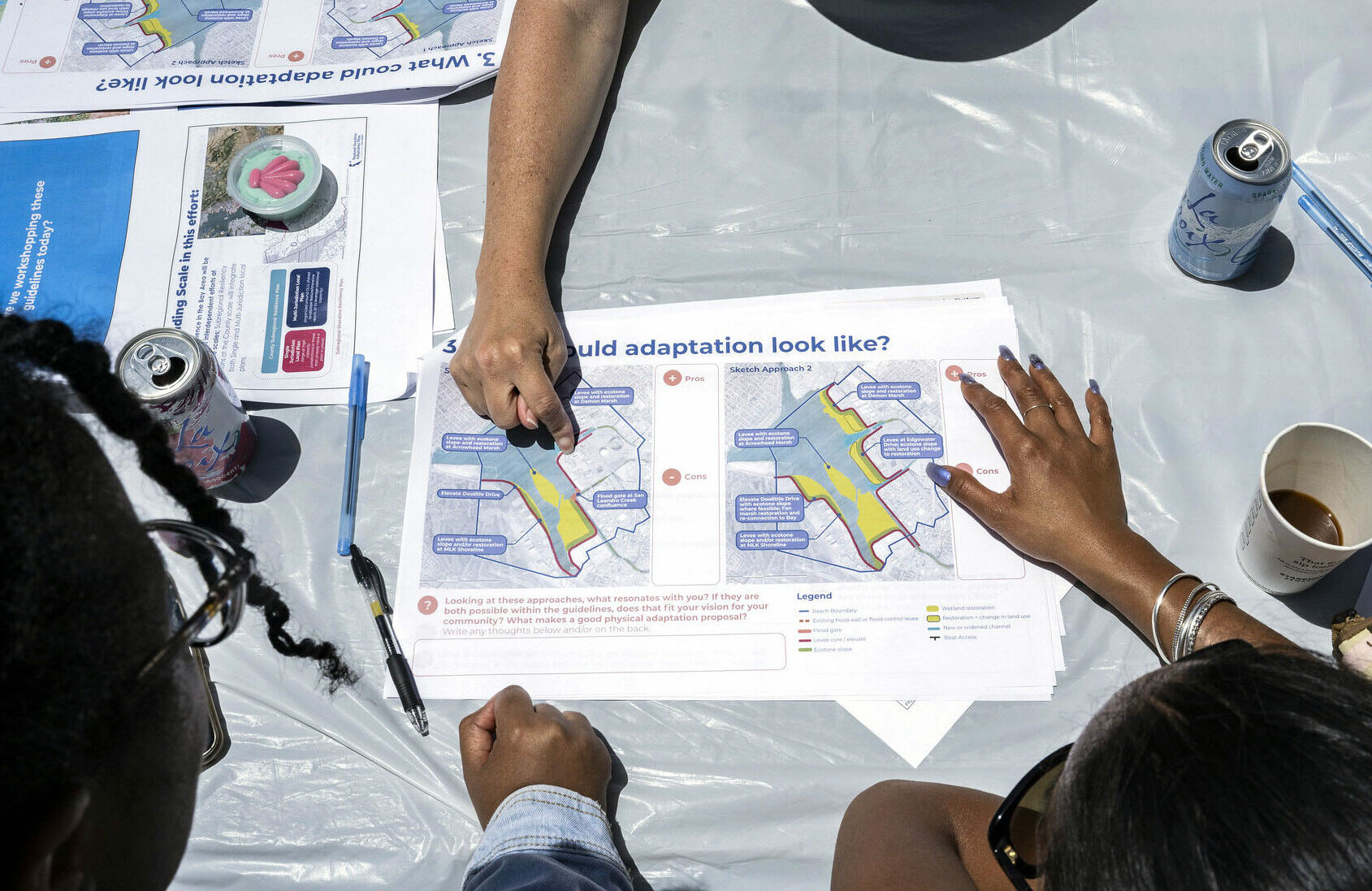

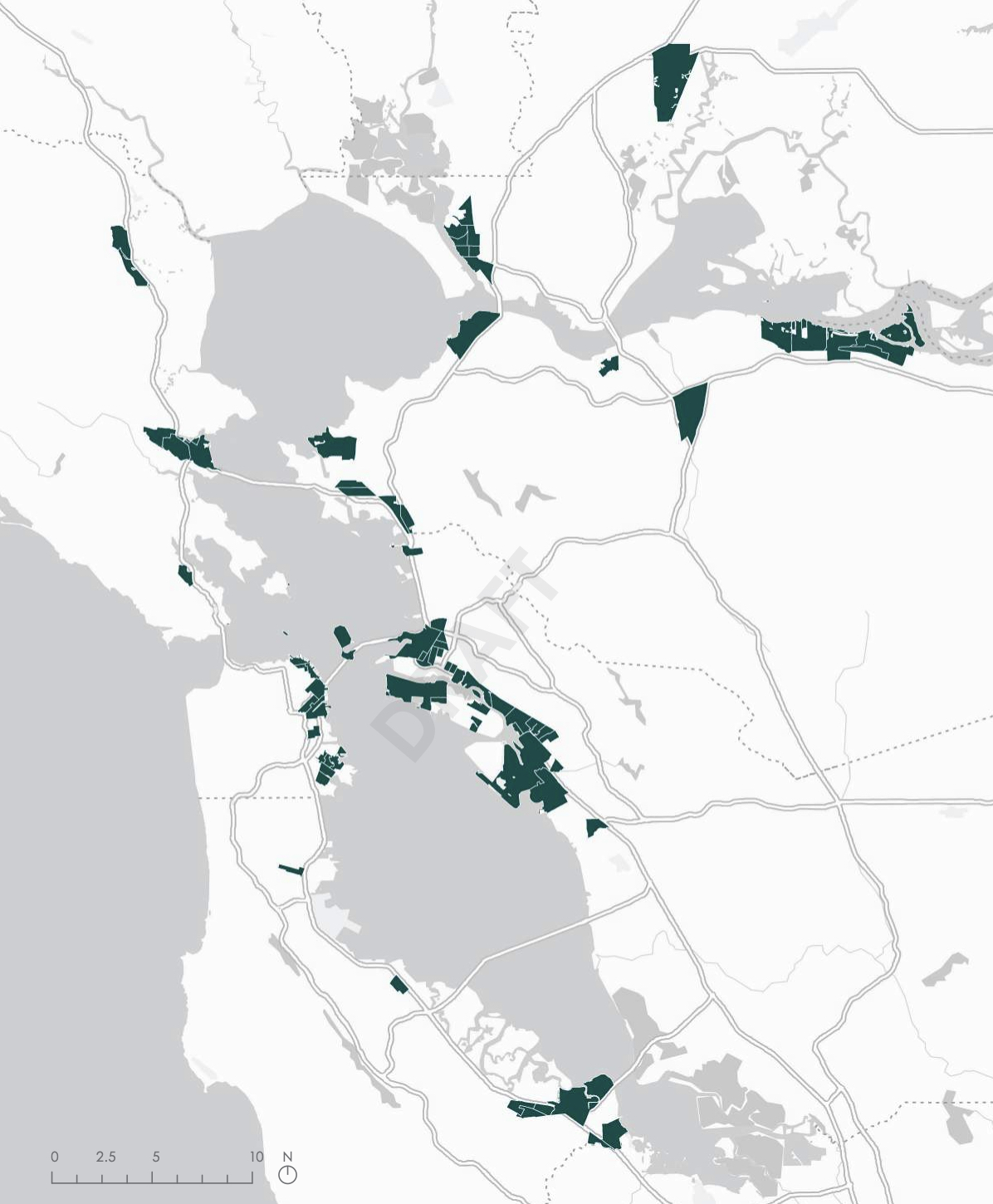

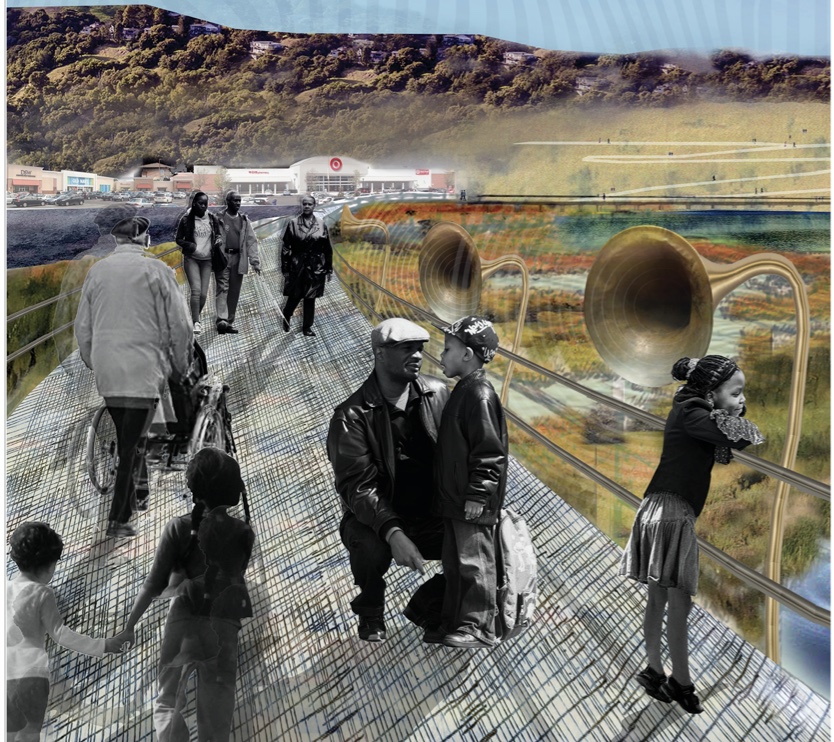

The third Standard demands fierce attention to equity concerns. There is a detailed questionnaire through which planners must prove they have done everything possible to consult and reflect the interests of the near-shore low-income communities, largely Black and Brown, that are now at disproportionate risk for flooding. BCDC has been working with grassroots organizations in several vulnerable spots. When it test-drove its planning model at workshops last summer, it went to Suisun City, Richmond, San Rafael, West Oakland, and East Palo Alto — “so that people in these places didn’t hear about this last,” says Hill.

Some activists see this round of sea-level planning as a chance to undo the old inequities. Anthony Khalil, of Bayview Hunters Point Community Advocates, told last spring’s Estuary Conference that “it’s planning for the future that’s rectifying the past. It’s about system change and not so much climate change.”

The fourth and last of these imperatives is the crucial one. Called the Adaptation Strategy Standard, it’s another long checklist that steers communities toward certain types of solutions and away from others. In keeping with BCDC’s mission, it prioritizes uses — from habitat to maritime commerce — that by definition have to be on the shore. It asks planners to look at “nature-based” shoreline protection modes, such as horizontal or ecotone levees, before retreating to any “harder” options like seawalls. It requires attention to systems and concerns that cross government boundaries. It calls for solutions that do it all, benefitting human communities and ecosystems alike.

This is familiar (to insiders), unexceptionable stuff. The realization, obviously, will be hard, especially in smaller or poorer jurisdictions.

Much work has already been done around the Bay on sea level rise, but the progress is spotty. Some communities are relatively far along and can plug prior work into the new plan (they are encouraged to do so). Others are barely at the “oh, my god” stage. BCDC points to the vast library of maps and other information it has to share, and will offer other technical support. “We want to act like the old country doctors,” says executive director Larry Goldzband. “We are going to do house calls. We are going to be in the cities, in the counties, with those staff.”

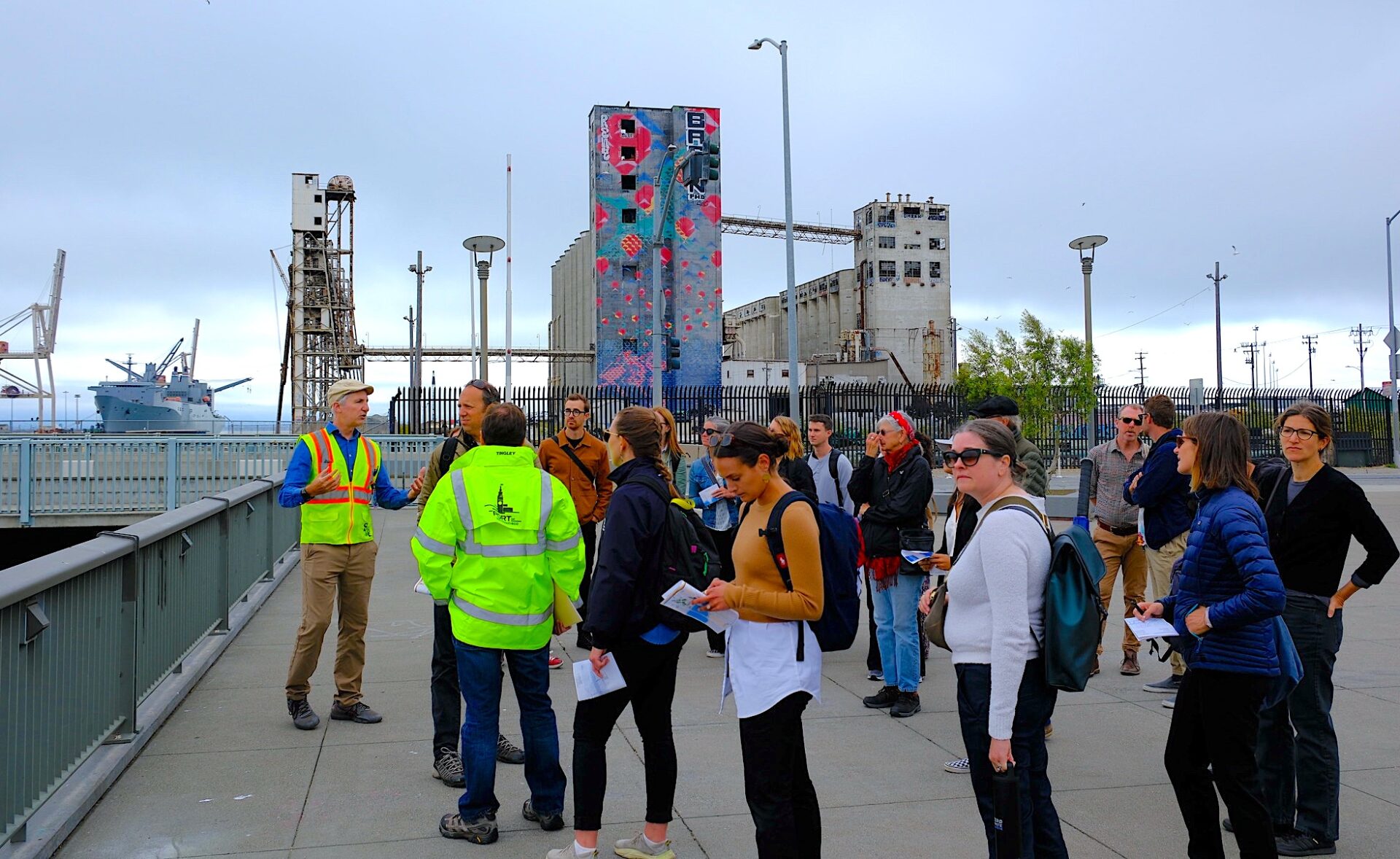

House calls in Richmond. A regional planning check in walk with a diverse group of planners, neighbors, and activists from Richmond this August. Photo: Karl Nielsen.

The doctors won’t be bringing money, but can advise on where and how to get some. The Ocean Protection Commission offers grants under the Sea Level Rise Mitigation and Adaptation Act of 2021 (SB 1). The California Coastal Conservancy has chipped in. So has CalTrans, through its Sustainable Transportation Planning grants. And this fall’s Proposition 4, nicknamed the Climate Bond, would open the money taps wider.

The nascent Regional Shoreline Adaptation Plan does its best to answer some obvious questions.

Can a collection of up to 44 local plans add up to a coherent regional one?

The RSAP incorporates the One Bay Vision, with broad, lofty goals, and flags many of its checklist items as Strategic Regional Priorities. The guidelines also urge jurisdictions to join forces wherever they can, planning for what the San Francisco Estuary Institute has called “operational landscape units,” such as embayments between promontories, regardless of boundary signs.

What about the players that are not included?

SB 272 speaks to cities and counties only. The special districts that do much to shape local life are missing. And, as always, the locals work in the shadows of powerful larger bodies: CalTrans, airports, utilities, pollution control agencies, government landowners, and the like. All the Bay Commission can do is to urge coordination — and a lot of interagency labor is already being devoted to this end.

Three big regional bodies have an outsize role. In a memorandum of understanding signed last summer, BCDC was given “prime” responsibility in the sea level planning effort, but CalTrans, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, and the Association of Bay Area Governments were dubbed “responsible” for it. Just how that plays out is unclear. The ultimate shoreline plan will become part of a future edition of MTC’s larger, kind of, sort of authoritative regional blueprint: Plan Bay Area.

Walking tour of Islais Creek flood zone as part of summer regional planning events. Photo: Justin Ebrahemi

What about BCDC’s own permitting process?

The agency continues to oversee land use on a narrow shoreline band. This function is not yet formally linked to the new planning; to change this would require a whole new hearing round and perhaps direction from the Legislature.

What about the plain fact that some shoreline tracts will at some point become unlivable?

The RSAP makes a shrewd distinction. It calls for protecting, across the board, communities that “are still very lively—people live there and they’re providing services and infrastructure.” But the authors observe that buildings and facilities have lifespans. When they wear out, replacement might have to be elsewhere. Governments should “plan for changes in land use, removal of assets, and/or equitable relocation.” Again, the plan calls for “policies, regulations, and/or financial incentives that allow for transitions at the end of the asset or development’s life cycle. Transitions can include shifts in land use to lower density or less vulnerable uses, or planned removal or relocation of assets.”

How fast can the planning happen?

The subregional plans are due by January 1, 2034. “Nine years is really a long, long time,“ remarked BCDC commissioner Patricia Showalter at a board meeting in August. “That’s the part that makes us unhappiest,” admitted Jaclyn Perrin-Martinez, RSAP project manager. But state money should be an incentive: jurisdictions that finish early will be first in line for funding to carry out their plans.

Who will complete the environmental impact reports?

Each jurisdiction (or group of cooperating neighbors) will have to subject its plan to an EIR before submitting it to BCDC. Dozens of separate environmental reports covering very similar questions? This seems like a formula for overlaps, challenges, and delay.

Created by Niba @notesbyniba

Interviews conducted from the deck of the Exploratorium’s Bay Observatory during the Rising Together Bay-Adapt Summit on rising sea levels in August 2024.

Will there be enough money to carry out what is planned?

This is a question no one can answer yet (but which the locals are supposed to confront in their documents). It depends on the winds of the economy and politics at several levels, beginning with the fate of the climate bond this November. In any case, the costs can be counted on to exceed any funding now in view.

As BCDC points out, the piper of sea level rise will, one way or another, be paid: either in the form of emergency responses, disjointed reactions, and outright losses — or, somewhat more cheaply, by plan. The agency estimates that the cost of protecting existing assets in place will be $110 billion by 2050; a more chaotic reaction would cost society at least double that. This calculation is probably realistic, but how often has prevention been an easier sell than cure?

At a BCDC webinar in September, the Sierra Club’s Gita Dev observed that free services provided by the Bay, including climate moderation, account for much of the region’s attractiveness and wealth. “The prosperity of the Bay Area is what is going to make this plan happen,” she said.

That’s hopeful. But first comes the planning itself.