Future-Proof Homes?

“We’re getting better at protecting ourselves, but there’s no foolproof way of building these days.”

Oona Khan dreams about her home of the future.

It will have a Jacuzzi in the back. It will have oak trees and succulents all around. The roof will be dotted with sprinkler heads. And it will stand in the same spot that her old house did — only this time, if a wildfire comes tearing through, all the power lines will be buried underground.

Khan, a retired physician, bought her house on a Malibu mountaintop in 2015. Three years later, the Woolsey Fire reduced it to embers. The lesson she learned, Khan says, is “it’s really up to you to do what you need to do to protect your own home.”

Caught in a quagmire of legal battles with her power company and surging construction costs in Malibu, Khan is still waiting to start construction. When — or if —she does get to rebuild, the home may bear a resemblance to her old house but it will be different: cognizant, in every way, of a changed climate future.

Remains of Oona Khan’s dream retreat in Malibu. Photo: Oona Khan.

And she is not alone. The homes we should be building now, and very likely those we should build in the coming decades, should reflect the climate pressures and weather threats we increasingly face, experts say. They should keep smoke out, and fresh air in. They should be fire resistant. They should perch high enough above the shore, or far enough away from it, that they diminish the threat of flooding. They could rely on the sun for energy, and a battery to store that energy on cloudy days.

The question is will they? And what will it take to make this change happen, both at the individual and societal levels?

“Everybody is operating under this kind of behavioral economics, which says, put it off as long as possible, I’m not going to be the one who gets unlucky, it’s going to be the house next door to me, that burns down, or it’s going to be the guy down the block whose house floods,” says Nate Kauffman, director of the Sustainable Environmental Design Program at the U.C. Berkeley College of Environmental Design.

But it’s also getting harder and harder to deny the imperative to adjust. “We’re all in a place right now where we’re recognizing increasingly just how much more frequently and severe these impacts are,” he says.

In Oregon, Jan Fillinger’s clients are starting to recognize that wildfires impact them, even if the blazes never make it to their front door.

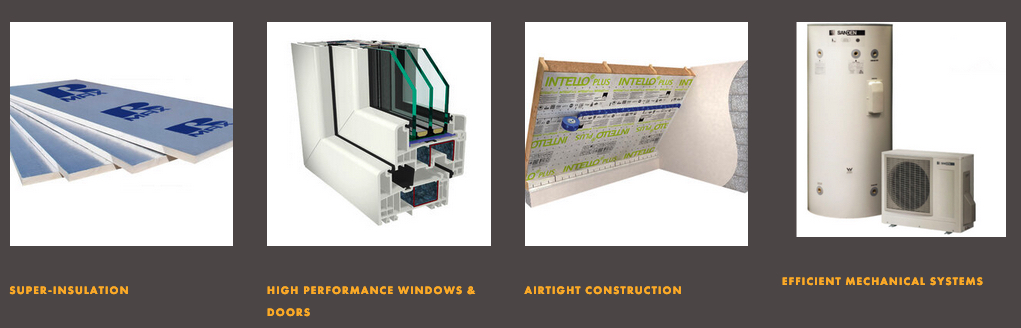

Fillinger’s website highlights some key elements of a resilient house. Image: Studio.e Architecture.

“The future is more [about] indoor air quality,” says Fillinger, an architect in Eugene, which has been inundated by smoke in recent years from fires in nearby regions. “We’re creating more of these pollutants and with climate warming, I don’t see wildfires stopping for years and years and years.”

Fillinger’s clients want homes that are as airtight as possible, which is a challenge, he says, because the buildings need to admit at least some outside air so the occupants don’t fill up the sealed home with their own, exhaled carbon dioxide. So Fillinger and his colleagues are working on creating new systems to better manage indoor air. One idea, he says, are ports that intentionally let outside air stream into the house, with a filter that cleans the air as it passes from exterior to interior. Another client has installed a filtration system that circulates and filters indoor air.

In addition to being airtight, homes of the future will be better insulated so they require less power to heat in the winter and cool in summer, he says. And the power they do need will be generated in different ways than today.

Instead of gas furnaces and electric air conditioners, our future homes will have environmentally sustainable heat pumps, Kauffman says. The homes may provide their own energy, via solar panels on the roofs — or roofs made of solar tiles — or even windows that capture solar power, he says.

That captured solar energy may not flow back into the electrical grid, because the home itself would have a battery, perhaps built into a wall in the house, that stores all the energy and powers the home. “It runs the water, the cooking appliances, the lights,” Kauffman says. It would provide, he says, “all the power we need.”

Heat Pump. Courtesy: BC Hydro

Such homes will be the environmental gift that keeps on giving, emitting less carbon dioxide over the decades that they exist. Environmentally-conscious architects these days “are concentrating on reducing our carbon emissions through reducing energy use in the building,” Fillinger says.

This effort to reduce carbon emissions extends to constructing homes as well, he says. Retrofitting an existing structure is more sustainable than building a new one, he says. Building with green materials is more sustainable than working with materials powered by or manufactured with fossil fuels, such as traditional cement, he says. And building a new home that can house multiple families is more sustainable than building one home per family, he says.

Unlike Khan’s home on a spacious mountaintop, homes of the future will likely be in denser neighborhoods that are less reliant on cars and more reliant on public transportation than today’s homes, according to experts in architecture and sustainable design. Our older cities already achieve some of these economies of scale. But, Kauffman writes in an email, many of these cities were designed and built decades ago, and their efficiencies are hobbled by crumbling infrastructure and outdated transportation systems and policies.

“I think that the infrastructure ‘aging’ is actually reflecting that the processes for planning, financing and constructing are aged! ” he writes.

Our future dwellings, if not self-powered, are sure to have to share more scarce resources, like land and power and water lines, with the homes of people around them. How that will exactly look is unclear: more houses bunched on fewer lots? More skyscrapers? Tall buildings that house many people minimize the use of certain resources, but also provide less space per person for rooftop solar panels, and use more energy to deliver water and elevators to higher floors, Kauffman said.

One thing is for certain: spacious homes on big lots with individual front and back yards are drains on our increasingly scarce resources.

“The absolute worst thing, sustainability-wise for the planet and our species, is that we keep building single family homes,” Kauffman says.

Even the most sustainable single-family house requires its own infrastructure, Kauffman says. “It’s a kind of system unto itself and it has a sort of metabolism,” he says. “All the homes pull in different things they do, they pull in gas in certain homes, they pull in water in every home, they’re hooked up to a grid where then you flush your water away, you rinse your water away. And so we have these networks, these vast public municipal infrastructure networks and the homes hook up to those things.”

But there isn’t enough land in many city limits to accommodate every family that wants a single-family house, he says, which leads to urban sprawl — mile upon mile of neighborhoods containing one-family homes that take over desert, forest, farmland, mountainsides.

Every time a new neighborhood gets built, Kauffman says, more pipes have to be run out to serve it, more garbage and delivery trucks have to drive on more roads to reach it.

And more people have to get in their cars and commute.

Years ago, as a young architect fresh out of school, Brian Holland experienced the impact of sprawl first-hand, when he had to drive two hours each way on Southern California freeways from his home in Glendora to his first job in Santa Monica.

Architecture class reimages a West Los Angeles suburb. Photo: Brian Holland.

Now an assistant professor of architecture at the University of Arkansas, Holland is still thinking about how cities like Los Angeles might function better in the future. Last year, he and his students won an award for a project called “Remixing Mar Vista.” It asked the Arkansan architecture students to re-imagine an iconic housing tract built in West Los Angeles in the late 1940s, for the 21st Century.

“I wanted students to work within a legacy single-family neighborhood with existing houses, to kind of densify it incrementally in a way that mirrored the processes that happen in the real world,” he says. In particular, he wanted them to see what they could do given new California laws that permit homeowners to build accessory dwelling units (ADUs) and, in some cases, multiple units, on properties formerly zoned only for single family houses.

“If you rethink what happens at the scale of the lot in the subdivision, eventually you make an impact on the ecological footprint of the city,” he says. “Because if you don’t change that model, it just continues to sprawl out and out, farther and farther.”

Up in Oregon, Fillinger’s clients are starting to respond to new zoning laws, asking him to design multiple units on the same property. One client wants “four living units on her tiny little property,” he says. The firm is still doing the code analysis to see if it’s possible, but the concept “is definitely the future,” he says.

Still, the vast majority of his clients who can afford to build new houses want to build single family homes, Fillinger says. And the sustainability questions then become: what is affordable, and how many sustainability modifications are enough?

Andrew Gansa has confronted those questions every step of the way, as he and his wife build their dream home in the hills above Calistoga, California. Flames have licked at the edges of the property before, most recently with the Glass Fire in 2020.

“We’re getting better at figuring out how we can protect ourselves,” Gansa says. “But there’s no foolproof way of building these days.”

Elements that make the Gansa home less prone to fire intrusion include no eaves, metal roof, cement plaster walls, few adjacent plantings, a Vulcan attic and underfloor venting.

In an effort to fireproof the new home, Gansa, who is also an architect, has designed a house that has no eaves where sparks can catch and spread flames to the roof. The roof itself is metal, the exterior stucco and the windows made of double-paned, tempered glass – all more fire resistant than the usual composite roof tiles, wood or vinyl siding, and untempered glass. The attic is outfitted with a Vulcan vent, which shuts off in case of flames, and sports concrete rather than wooden decks.

But Calistoga’s Gansa, for instance, opted out of sprinklers on the roof. By contrast, Malibu’s Khan doesn’t want to rebuild without them. She believes a neighbor’s house survived the fire that demolished hers because his roof sprinklers doused enough water on the structure that the blaze couldn’t gain traction.

Holland’s students Avery Boland and Avery Lake redesign Mar Vista with more units and fewer cars. Art: Boland & Lake

Despite the passage of four-plus years, Khan hasn’t been able to start rebuilding. The local per-square-foot cost of construction quadrupled in the blaze’s aftermath, she says, driven skyward by ultra-wealthy neighbors for whom money is not an object. She and other neighbors are suing their power company, Southern California Edison, over the power lines that allegedly crashed down on properties and sparked more fires. A settlement from that suit, combined with her insurance money, would allow her to move forward with rebuilding, she says.

Driveway to Khan’s home pre-fire. Photo: Oona Khan.

In the meantime, Khan and her disabled brother, Ash, live in the nearby home they inherited from their deceased parents. They could sell their ranch property that burned; there are no shortage, she says, of willing buyers. But it’s the place of her dreams.

“It’s three acres overlooking this beautiful vineyard,” she says. “And the view is amazing. The property is amazing. It was my haven for the three years that I had it.”

“I love that spot, you know?”

More

KneeDeep does not endorse these products.