New Flood Protection Standard for the Peninsula

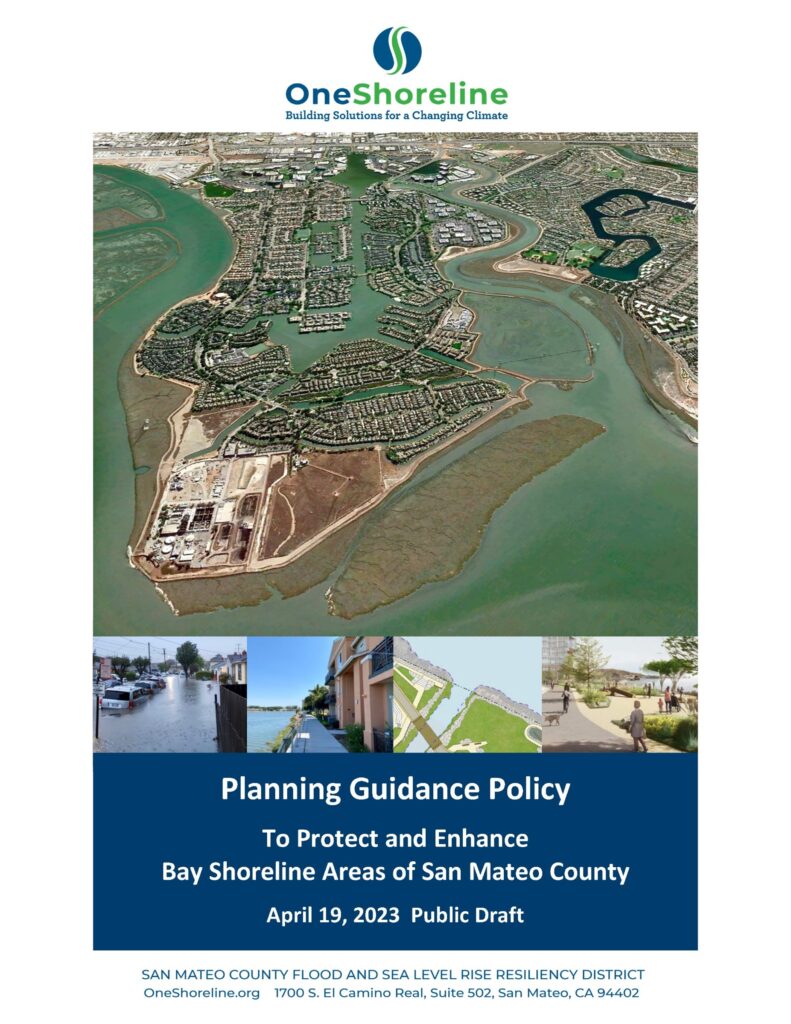

By the end of the century, the State of California is projecting between one foot and ten feet of sea level rise. In San Mateo County, new planning guidance may help cities account for rising seas when approving new developments.

“Incorporating future conditions requires a really, really big perspective shift,” said Makena Wong, a project manager who worked on the guidance, in a recent public meeting. “We’re trying to make that shift as practical as possible.”

The new guidance is voluntary. It comes from OneShoreline, a countywide flood and sea level rise resiliency district, and includes maps and templated language that cities can use in general plans, specific plans, and zoning laws. OneShoreline can help cities with implementation. Residents can also ask the organization to comment on whether proposed developments meet the new standards.

Friday, May 19 is the last day to submit public comments; a final draft should be approved in June.

OneShoreline’s proposals are stricter than current requirements from federal, state, and local agencies, but those requirements are also evolving. “The intent is to go where we already see regulators are going,” Wong said. The goal is to help cities and developers avoid locking in less-resilient projects.

The core recommendation is a stricter standard for shoreline levees. Today, the Federal Emergency Management Agency requires that levees stand two feet above the expected high-water mark during a hundred-year flood (or, in some cases, that height plus waves). Short of that standard, the land behind levees needs mandatory flood insurance; OneShoreline is recommending six feet above instead, to protect against rising seas.

The guidance notes that gradually sloped levees—as opposed to walls—can help slow big waves during storms. Sloped levees built to the proposed, higher standard would protect the shoreline during a 100-year storm surge even after three feet of sea level rise. In calm conditions, they would protect against a bay nine feet higher than today’s.

The State of California recommends that communities plan for 3.5 feet of sea level rise by 2050 and six feet by 2100. Actual sea level rise could be slightly lower or higher. Some is already locked in; the rest depends on how much humanity can reduce fossil fuel emissions.

Other recommendations in OneShoreline’s guidance include setting developments back from the shore and from creeks; making sure new developments can effectively absorb and divert storm water from increasingly wet atmospheric rivers; and making it easier for levees to get built—either by incorporating them into developments from the start, or by making sure cities retain the right to build later without resorting to eminent domain.

The guidance focuses on new private development; it does not address existing buildings, new non-commercial construction, or government projects like retrofitting buried infrastructure to account for challenges like more liquefaction during earthquakes. OneShoreline hopes to address those issues in the future.

For now, the goal was to act fast. Many Peninsula cities are in the process of evaluating commercial shoreline developments and new affordable housing. According to OneShoreline CEO Len Materman, more than one third of proposed affordable housing on the Peninsula would be vulnerable to floods now or in the future.

“Moving it out of harms’ way,” Materman says, “that’s the first approach that we suggest.” But, he says, a “managed retreat” approach to flood zones is usually a political non-starter.

Instead, OneShoreline worked with cities and developers to create standards that provide better protection for new developments—and the properties around them—in areas vulnerable to rising seas, rising groundwater, and flooding from atmospheric rivers.

Similar guidance is on the way from state agencies, including from the Bay Conservation and Development Commission, but it is a year or more off. “We just felt we had to move more quickly,” Materman says. “We are hoping that this pushes people.”