Fighting Chance for Marin’s Forests?

“We’ve learned that a good healthy forest is much less likely to burn badly.”

In the era of climate change, forests across California seem doomed to retreat, ceding millions of acres to chaparral and annual grasses. But maybe not everywhere. In at least one coastal county, there seems to be hope of keeping valued woodlands healthy, if not unchanged — provided that some past mistakes can be corrected, fast.

This is the message of the new Marin Regional Forest Health Strategy, from the consortium called One Tam: the National Park Service, California State Parks, Marin Water, Marin County Parks, and the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy. These agencies — joint custodians of public lands centered on Mount Tamalpais — each have their own ideas and authorities.

But, says Daniel Franco of the Conservancy, they share a vision: “The one thing we all agree on is managing the vegetation mosaic that now exists.” Even when duly qualified — the strategy acknowledges the mosaic may shift — this is a bold, almost astonishing goal.

The Strategy is the latest in a series of studies going back to One Tam’s Peak Health inventory of 2016, and the first to look beyond the greater Mount Tamalpais area to cover the entirety of Marin, including private lands. It also strives to integrate two needs: long-term forest health, and the safety of the human communities that adjoin and often colonize the kingdom of the trees. “The One Tam people have done amazing work,” says Mark Brown, executive officer of the Marin Wildfire Prevention Authority.

The county has some 118,000 acres of woodland, covering about one third of its area. One Tam directs its attention to five forest types in particular, identified by their keystone species: the iconic coast redwood; the sometimes equally impressive Douglas-fir; the picturesque, fire-dependent Bishop pine; the rare Sargent cypress, limited mostly to serpentine soils near Mount Tamalpais; and oaks in grassy settings, most important of all in Coast Miwok Indian life.

Among these types, redwood and cypress seem at least to be holding their own. The Bishop pine, whose cones need heat to open, is suffering especially from overzealous fire suppression. The same lack of fire has given a temporary boost to Douglas-fir; this species is now expanding its range at the expense of grassland and brush. Of all these treescapes, it seems the community of widely spaced oaks — notably coast live, valley, and Oregon white — is under the most stress. Besides past losses as cities sprawled over oak-friendly valley floors, almost half of the remaining open canopy oak woodland is threatened with conversion to Douglas-fir.

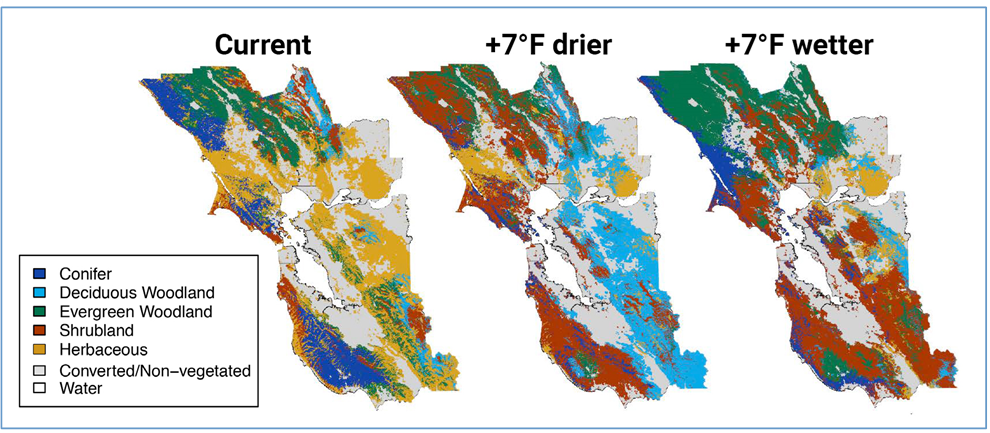

Vegetation types will change with climate change. Current and predicted vegetation types for the Bay Area modeled using temperature, precipitation, and climatic water deficit predictions under 7 o F drier and wetter climate models. Source: Ackerly et. al., 2015; Chomesky et al., 2-15.

That’s what is happening now. But what is likely to happen as warming inexorably proceeds? In 2015, researchers tried to map the vegetation types that would prevail if the Bay Area warmed by seven degrees Fahrenheit and under two different rainfall regimes, wet and dry. In Marin, brushlands expanded hugely in both scenarios, though in different patterns. In the dry version, coniferous forests shrank. In the wet, they moved north, almost abandoning Tamalpais but taking over grasslands on either side of Tomales Bay. The grasslands fared worst in the county, shrinking back northward in the dry future and almost vanishing in the wet.

Two years after that report, however, a differently focused study suggested that plant communities in “central western” California, including Marin, might prove exceptionally resilient to the coming heat wave. The Forest Health Strategy seizes on this lifeline, seeing a future in which at least some of Marin’s coastal forests hold their own and become what climate scientists call refugia, redoubts where ecosystems can ride out the century or more of heat to which past human actions now doom us.

Rich in information, the Forest Health Strategy might better have been called the Forest Health Baseline or Forest Health Framework. When it comes to proposed actions, it is a little thin, calling repeatedly for research, the testing of different tools, and cooperation among agencies and with the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria. The Recommendations section can almost be skipped. (“The document itself really isn’t a prescription,” acknowledges Daniel Franco of the Parks Conservancy.) But some big ideas are scattered through the thousand-page text.

A major theme is a new role for fire. The landscape needs to shift back toward what it was when fires, both natural and set by the Coast Miwoks to increase yields of food and fiber, were much more frequent. Under the modern regime, open woods with sparse understory have given way to crowded, flammable forests with much brush and many small trees. The blazes, when they come, tend to be harder on the forest, and more dangerous to residents nearby.

Forest health and wildfire prevention used to be seen as opposing goals, says Brown. Fire agencies often bulldozed barren firebreaks along ridges, causing soil erosion and a seedbed for invasive species. Now firebreaks are made by removing underbrush, leaving larger trees intact. “We’ve learned that a good healthy forest is much less likely to burn badly.”

Much of Marin’s forest is too overgrown to permit a simple reintroduction of fire. In many areas, a hand-clearing phase has to come first. The task may seem huge, but Brown is encouraged by detailed mapping done since 2016. The Mount Tamalpais watershed, for instance, contains natural pathways along which fire travels and where it burns hottest. Manual thinning along such corridors — just a fraction of the total area — could help turn catastrophic fires into more beneficial ones.

One goal of such management is to nudge young redwood and Douglas-fir forests toward an old-growth condition, with fewer and larger conifers and thinner layers of shrubs and mid-sized hardwoods underneath. It is thought that the redwoods can survive even the fiercest fires that the future holds.

The outward march of the Douglas-firs, however, needs to be stopped in some places, especially where it replaces valued oaks. Again, manual clearing and burning are tools, and so is grazing. In some places oaks may have to be planted. The Coast Miwok community is called upon as a key partner here, though much more is said about what the indigenous managers used to do than about what they might do now. It complicates matters that so much oak woodland is on private rather than public or tribal land.

The Conservancy’s Franco cautions against assuming that woodlands, and vegetation types in general, will remain exactly where and how they are. “At some point there will be a mismatch between communities and their preferred climate envelopes. We know it’s going to change.”

It’s a comforting thought, however, that here along the relatively cool coast the mismatch might be less than catastrophic — that here, at least, the forests, and the people who care for them, have a fighting chance.