East Oaklanders Stand Their Ground, Rethinking Ballpark, Transit & Rising Bay

“We’re trying to bring more cultural vibrancy to the shoreline.”

On a sunny, serene October Saturday couples stroll along the Bay Trail, passing a small group of photographers taking aim at a great blue heron from the walkway overlooking Arrowhead Marsh. Bird calls carry over the calm water of Oakland’s San Leandro Bay, but suddenly a different noise makes me and a dozen others waiting along the shoreline lift our heads in anticipation. A deep bass beat cuts into the quiet, growing louder when twenty or so bikers appear on the trail. These riders are not the usual spandex-clad blurs crouched over expensive road bikes: this group is dotted with jeans and hoodies, yellow safety vests, and afros and dreadlocks that bounce in the wind. Several flash brightly decorated spokes in the style popularly known as Scraper Bikes. Unlike the rest of the several dozen people out enjoying the fine day at the Martin Luther King Jr. Regional Shoreline, this group is mostly Black and from East Oakland.

Smooth rap music blasts from a mobile sound system on a bike trailer, and the riders pull up grinning to a few cheers. They have ridden from Liberation Park in East Oakland to the shoreline, battling encroaching cars and deteriorated streets with no bike lanes as they rode down 73rd Avenue and Hegenberger Road, across train tracks, and over the I-880 freeway. Some of the riders have lived in East Oakland for decades, and it’s their first time taking this path to their own waterfront — one besieged not only by urban development, but also a rising Bay.

“We’re trying to bring more cultural vibrancy to the shoreline,” says the East Oakland Collective’s Keta Price, who organized the ride. “If you’re not a straight-up nature lover then it’s bland, and so we are thinking of different ways to get residents [here].” To that end the event includes games and raffle prizes, and music by local DJ Outta Pocket, whose thumping beats compete with the occasional harsh overhead roar of an airplane or engine cough from the freeway — all of which bounce off the water lapping at the shoreline.

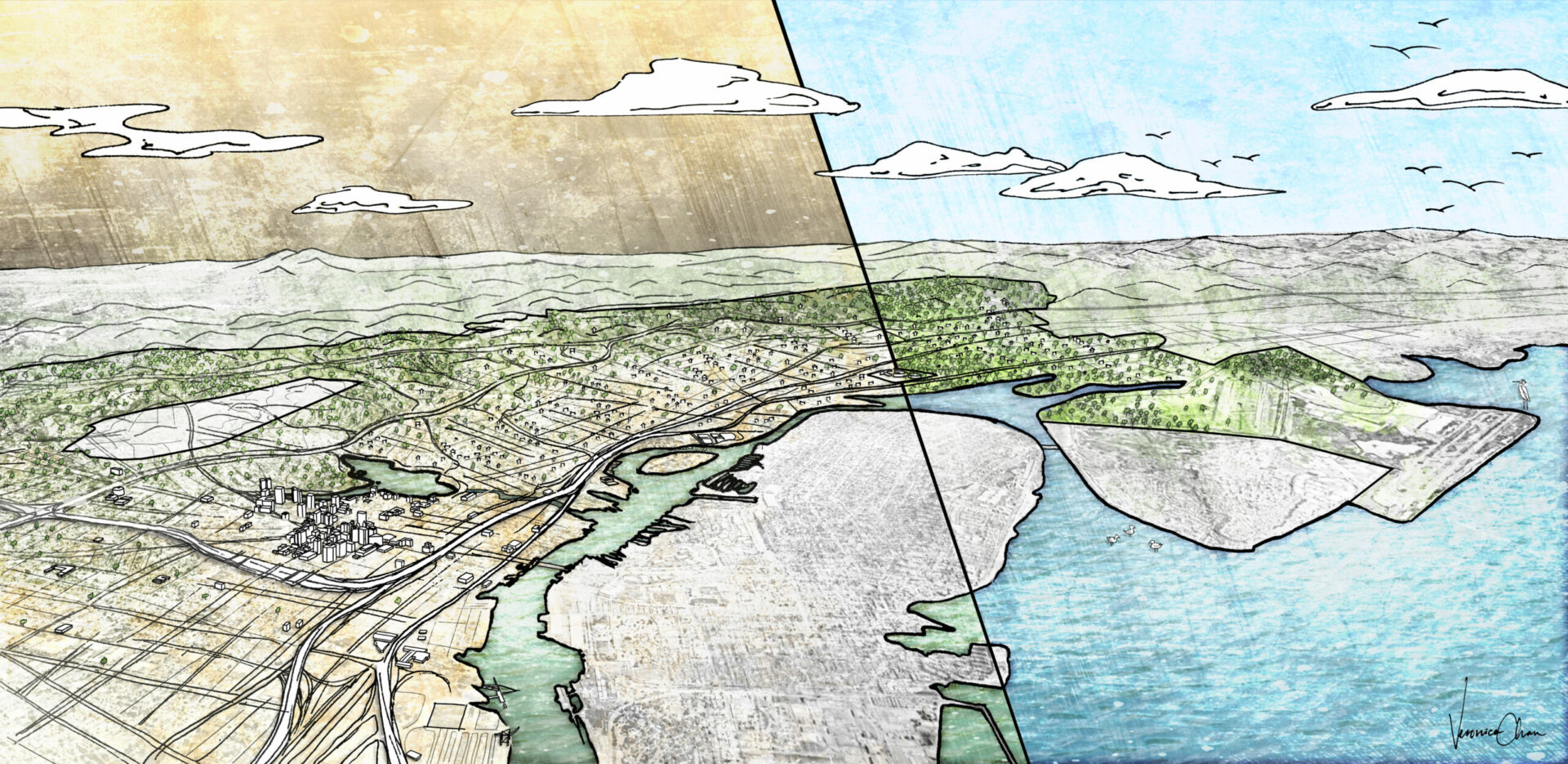

Envisioning a greener, more resilient future for Oakland begins with the landscape.

Art: Veronica Chan.

A Taken Waterfront

The Martin Luther King Jr. Regional Shoreline is owned by the Port of Oakland but managed by the East Bay Regional Park District, which, Brian Holt tells me, has paid the Port $1 annually since the 1970s for the privilege of investing hundreds of thousands of dollars per year in natural resource management, recreation, and maintenance activities.

I ask Holt, the chief of planning, GIS, and trails for the park district to describe the shoreline, and he lauds its uniqueness in the crowded waterfront. “It’s a beautiful oasis on the Bay that is under-appreciated and under-accessed,” he says. “It’s a respite in an area surrounded by industrial and infrastructure uses, and of course residential use.”

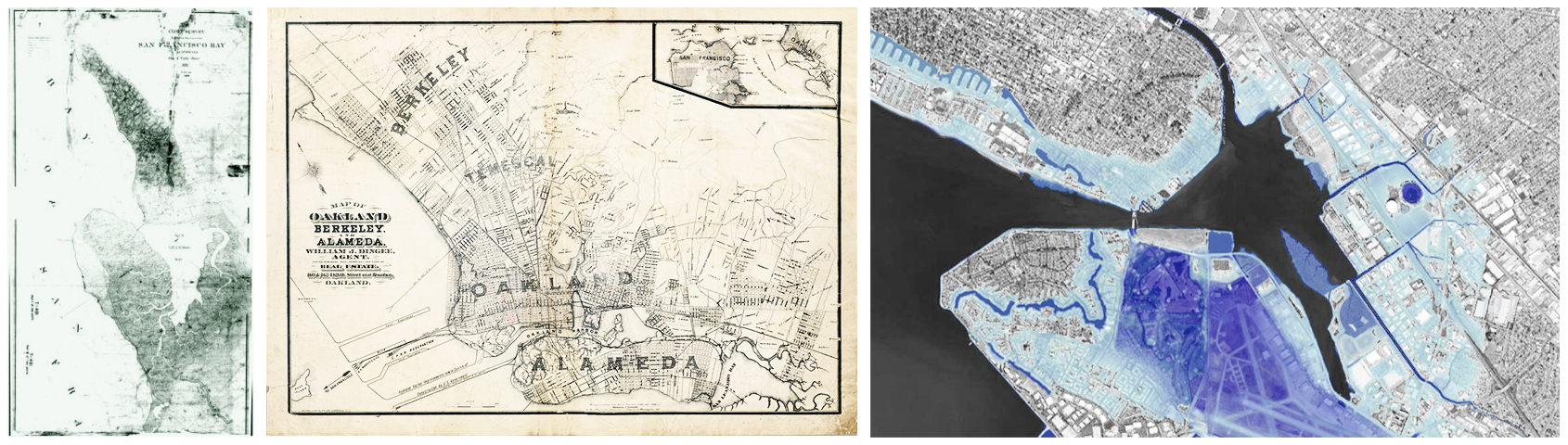

How East Oakland’s waterfront came to be hemmed in by rail, roads, and industry begins with an audacious land grab in the early 1850s, when San Leandro Bay was encircled by a 2,000-acre marsh nearly 15 times the size of Lake Merritt. Through a combination of political connections and bold-faced chicanery, lawyer and ferryman Horace Carpentier got himself elected Oakland’s first mayor. He quickly convinced the newly formed city council to deed him the entire waterfront in exchange for his promise to build wharves and a schoolhouse — all before most residents were even aware that the freshly incorporated City of Oakland even existed.

With the arrival of the Central Pacific railway in 1869, train yards and tracks crisscrossing the shore to serve ferries and slaughterhouses, mills, and lumberyards quickly ate up more of the waterfront. It took Oakland nearly 50 years to regain control over its own tidelands, which by then were crowded with ship-building, metalworking, and machinery industries; as well as factory food processing and canning.

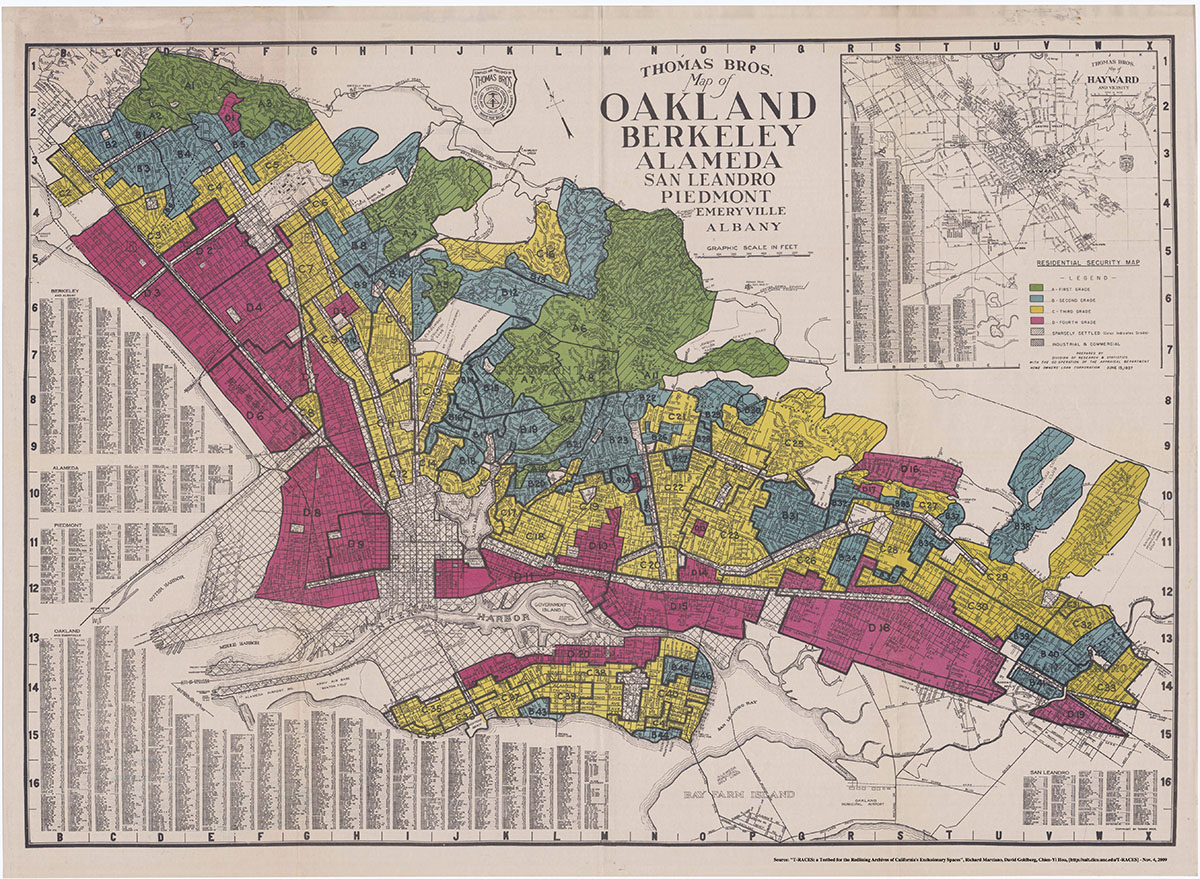

In the 1930s and ‘40s local industry switched to military and automobiles, and an influx of Black Southerners arrived to work in World War II factories. The U.S. government rewarded their service with racist redlining practices, denying them home loans and effectively suffocating community investment in East Oakland.

Historic Brooklyn Basin.

Today’s boom and bustle surrounding the East Bay shoreline makes its role as refuge for both wildlife and people even more important. “Certainly, the MLK shoreline being buffered between the airport and the 880 represents some of the most difficult access challenges,” Holt says. “Having easy access to these places is critical, and it’s part of what makes a community.”

Over the decades, obstacle upon obstacle has been placed between the East Oakland community and San Leandro Bay. The remaining sliver of public shoreline clings to the land like a barnacle in an entangled sea of warehouses, industrial yards, and roadways — all built with no idea that one day the water might rise.

There Are No Natural Disasters — Only Social Ones

Unfortunately, all of that waterfront infrastructure will do little to stop sea-level rise. But even before that happens, East Oakland is already in a precarious position.

“We are looking at characteristics that make people more vulnerable,” explains Andrew Slocombe, a research scientist with the California Environmental Protection Agency. He is patient and affable as we chat, which is good because I called him after a few depressing hours staring at the agency’s CalEnviroScreen mapping tool, toggling through 21 indicators like poverty, ozone emissions, pesticide use, and more while watching the map of East Oakland’s census tracts turn dark and foreboding colors for most of them.

In fact most of East Oakland is rated around the 90th percentile for “Pollution Burden,” meaning the community experiences more pollution — across 13 measurements ranging from diesel emissions to toxic waste sites — than 90 percent of all other communities in California. This is an enduring inheritance from the Port of Oakland, roads and railways, and ghosts of long-gone military and auto industry factories hanging around to haunt the area in the form of legacy contaminants and brownfields pockmarking East Oakland.

Downtown Oakland oscillates between gentrification and deterioration, but open spaces improve quality of life for most. This new park memorializes the early industrialist and shipbuilder Henry J. Kaiser, who left a legacy of contaminated waterfronts to the city.

Photo: Lonny Meyer.

East Oakland’s score for “Population Characteristics,” an index of socio-economic and health attritbutes like housing burden, education level, cardiovascular disease, and more, similarly rates among California’s worst. But like a good scientist, Slocombe cautions against drawing conclusions from the data.

“It’s not cause and effect,” he says. “For example, heart disease is not [always] caused by pollution but it is something that makes people more vulnerable to pollution effects in the area.” For East Oakland, this means that despite an asthma rate in the 99th percentile, scientists cannot say for sure that it’s because of high levels of pollution. But they can say that East Oakland’s high asthma rate means residents are more likely to be hospitalized by poor air quality than people in Piedmont, for example, who despite being only 10 miles away are in California’s much lower 21st percentile.

First released in 2012, the CalEnviroScreen tool is garnering more attention as public awareness regarding environmental justice and social resilience has grown. “I think interest has increased with each version we’ve done,” Slocombe says of the model that is currently on its fourth iteration. “To have a way to view vulnerabilities and disadvantages means more objectivity, not just who argues the best case.”

One recent analysis that builds on CalEnviroScreen’s efforts is the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC) regional sea-level rise report released last year. The analysis rated all shoreline Bay Area communities for twelve “social vulnerability indicators” such as low income, lack of vehicle ownership, number of households with small children and elderly — all signals pointing to neighborhoods and populations who might struggle more than others in responding to, and recovering from, a flood. East Oakland is in the 90th percentile 11 of the indicators, and in the 70th percentile for the last one. [Disclaimer: I previously worked as a sea-level rise planner for BCDC, but was not part of this analysis].

Evolution of the San Leandro Bay waterfront, from early marsh and tidelands (left) to early real estate boom (middle) to industrial zone and low-lying neighborhoods now threatened by sea level rise (right). BCDC mapping tool shows projected flooding from a 66-inch increase in water level, equivalent to 3 feet of sea-level rise plus a 25-year storm.

This vulnerability already exists today, even before rising sea levels threaten to flood large swaths of East Oakland. As bad as they look on the map, these projections don’t include groundwater flooding, which recent research identified as an aggravating factor in East Oakland.

What this projected level of flooding actually means for East Oakland, however, is unclear. Despite a raft of local flood studies by a half-dozen agencies, most narrowly examined sea-level-rise risk and vulnerability of infrastructure like the 880 freeway, the Amtrak railway, or the Coliseum Bart station. Even Arrowhead Marsh has been studied: according to the United States Geological Survey, rising seas will drown the last fingernail of marsh hanging on to the San Leandro Bay by 2080. But the glaring absence of a single study focused on the flood risks and consequences for the East Oakland community — one of the most vulnerable in the Bay Area and California as a whole — speaks volumes.

There is a saying that there is no such thing as a natural disaster, only social ones. The rationale is that absent people, the earth’s movements and rhythms are simply nature. But when people and societal inequities are placed in harm’s way like in East Oakland, analyses like CalEnviroScreen and BCDC’s highlight existing societal cracks that events like a powerful storm or the Bay rising several feet will expose and widen.

The Uncertain Path Forward

In recent years, wealthier cities like San Francisco, Foster City, and San Jose have allocated hundreds of millions of public dollars to fortify their shorelines. East Oakland has no such funding. Its best hope at the moment appears to be the massive multibillion-dollar redevelopment of the Coliseum area, which offers a chance for needed community investment and infrastructure improvements to reduce vulnerability of the surrounding neighborhoods. But repurposing the 155-acre sports complex and its vast open space has been a subject of prolonged tug-of-war over local priorities and who stands to profit.

“[The Coliseum redevelopment project] could provide a lot of opportunity for East Oakland, which is facing a crisis of affordability and a number of families have already been pushed out,” says Liana Molina, Oakland senior campaign director with East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy (EBASE).

EBASE convened a broad community coalition of labor groups and youth- and faith-based organizations in 2013, when the Oakland Raiders first proposed a new stadium as part of a grand “Coliseum City” plan. The issues raised back then by the coalition, dubbed Oakland United, are the same priorities that Molina ticks off rapid-fire to me today: affordable housing, community legal services, living wage and local jobs, and on the environmental side, mitigating the abandoned contaminated industrial lands while increasing green space and access to the Bay.

Eight years later, however, both the Raiders and the Golden State Warriors are gone, leaving behind only broken promises. The Athletics continue to threaten departure to Las Vegas if their conditions for a new baseball stadium at Howard Terminal aren’t met, meaning who develops the Coliseum area — let alone how — is still a muddled question. The A’s, whose Coliseum stadium lease runs out in 2024, purchased a 50% stake in the Coliseum redevelopment from Alameda County in 2019. The other 50% is owned by the City of Oakland, whose city council just recently granted a Black-led development group exclusive negotiating rights to purchase or lease the city’s share in the Coliseum area.

According to Molina, the chosen bidder — the African American Sports and Entertainment Group — and the city council have been receptive to Oakland United’s goals of a minimum of 35% affordable housing, and 50% of the jobs for people who have historically faced barriers to employment, like the formerly incarcerated and chronically unemployed. “We are cautiously optimistic,” she says, pointing out in contrast the A’s have consistently tried to minimize their responsibility to provide meaningful and positive community impact.

How the process will play out for East Oakland is still unclear. But unlike sports franchises, the community isn’t going anywhere — and they aren’t standing still. Oakland United coalition members are pushing for a pedestrian bridge over the freeway to access the Bay, a community resilience center, and reducing the heavy pollution burden that ranks as one of the worst in California. Keta Price and the East Oakland Collective are organizing events to highlight stories from community elders about their waterfront, participating in the Oakland Shoreline Leadership Academy to help train citizen planners and advocates, and breaking through both physical and cultural barriers by getting residents to bike, walk, and kayak their own shoreline. (Don’t miss KneeDeep’s Lifting Up Local Knowledge video on the academy).

What does rooting a community to its waterfront have to do with adaptation and resilience? It took 100 years to chop down waterfront stands of oaks, fill in wetlands, and cut off most of Oakland from its shoreline by a tourniquet of industry and transportation. By reclaiming the shoreline that stands between them and the rising Bay — one that many outsiders and agencies look at solely in terms of transit assets and development potential — the East Oakland residents are ensuring they have solid ground to stand on when the time comes in boardrooms and public hearings to fight to protect their community from the water rising around them.

At the shoreline bike ride event, during a break in DJ Outta Pocket’s set, the smiling, ebullient Keta takes the mic to welcome everyone, thanking local organizations like Higher Ground, the Black Cultural Zone, and Chef Mikhael from Black Seed Cuisine, who provided food for participants. When I first met Keta in 2018 to talk with her about sea-level rise in East Oakland, she told me her community is “hella resilient” because of events like this one, which reinforce neighborly bonds and relationships for a population that has survived so much already, often with little outside assistance and only each other to rely on.

At the end of Keta’s impromptu speech the music resumes, its rhythms wafting through the warm October air to the people at picnic tables eating wings and Mikhael’s seasoned grains and vegetable dish, intermingling with chatter and laughter, and birds chirping in the marsh nearby. Seeing this strength of community — something not factored into CalEnviroScreen nor BCDC’s report — is almost enough to make me believe her.