“The embankment can’t be a continuous barrier.”

Like many of her fellow Solano County residents, Kendall Webster’s job is in another North Bay county that is wealthier and so less affordable. These days she works from her Vallejo home but, when pandemic restrictions lift, Webster will join the throng commuting to Marin and Sonoma counties along Highway 37. She’s dreading it already. This 21-mile waterfront road is among the Bay Area’s most vulnerable to sea level rise, and is already inundated during wet winters. When the record-breaking rains of 2019 hit, flooding shut down Highway 37 repeatedly. “I don’t know what I’d do,” Webster says.

To help keep Highway 37 open despite heavy storms and rising tides, planners are assessing a wide range of options from elevating the road to rerouting it. But zeroing in on the right redesign may be trickier than anticipated. New research shows that, with sea level rise, protections for this troubled North Bay road can worsen flooding and economic damages as far away as the South Bay. The good news is that this work can also identify Highway 37 redesigns that avoid these catastrophic impacts.

Besides having a personal stake in the future of Highway 37, working on a fix is part of Webster’s job at the Sonoma Land Trust. “We want the design to be compatible with restoring the Sonoma Baylands,” she says, referring to the diked agricultural fields along the northern arc of San Pablo Bay.

These fields were originally part of an expanse of tidal marsh between Vallejo and Highway 101 in Marin County. When Highway 37 was built nearly a century ago, it cut straight through these marshes. “It’s a silly place for a road,” says Jeremy Lowe, a San Francisco Estuary Institute geomorphologist who has worked on the Bay for two decades and, like Webster, is working on a fix for Highway 37. “Ideally it wouldn’t be there — but it is.”

The environmental community’s official involvement in planning Highway 37, formally known as State Route 37, stems from Webster’s early days at the Sonoma Land Trust. Charged with conserving and restoring the Sonoma Baylands, she began sitting in on the planning meetings five years ago “just to keep an eye on them.” Next she helped form the State Route 37 Baylands Group, a Coastal Conservancy-led advisory body that includes Lowe and others dedicated to a highway redesign that is in keeping with ecological restoration. Now, Lowe is part of a Highway 37 technical working group, a key part of the planning process that brings restoration practitioners and transportation engineers together to work out nitty gritty design details.

This is a fundamental shift in transportation planning, which typically puts design before environmental review. “We’re saying ‘let’s look at the environmental impact first and then move forward on design,'” says Webster, who used to be on the planning side herself. “I’ve worked at Caltrans and experienced the way it operated from the inside — it’s really gratifying how it’s evolving.”

Incorporating ecological considerations into the Highway 37 redesign will minimize environmental damage as well as the considerable costs of compensating for that damage. Lowe credits one of the transportation planners with describing the new approach as “integrate, not mitigate.” Moreover, considering environmental impacts at the front end will let planners accommodate future marsh restorations.

Now, instead of being presented with a done deal on Highway 37, the Baylands Group is in constant dialogue with the Bay Area’s Metropolitan Transportation Commission, the Sonoma County Transportation Authority, and California Department of Transportation. “We need to look at this from all viewpoints,” Lowe says. “Getting people together early in the planning process is a model for the rest of the Bay.”

As the restoration community began weighing in on Highway 37, a team of researchers led by Michelle Hummel, a civil engineer at the University of Texas at Arlington, began evaluating the redesign options laid out by Caltrans in 2015. She had previously discovered that, with sea level rise, a seawall or levee in one part of the Bay could exacerbate flooding in another. “The extent and magnitude of these interactions really surprised us,” says Hummel, who began this work as a graduate student at UC Berkeley. “Impacts can extend all the way across the Bay and from one end to the other.”

Hummel’s latest study, reported this summer in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, compares the impact of rebuilding Highway 37 on a raised levee or embankment that blocks tidal flows versus on a causeway that lets Bay tides reach the marshes. The study showed that, with sea level rise and during the highest of high tides, an embankment could intensify flooding in San Jose and cause $293 million in damages. This cost is an underestimate as the researchers only included damages to buildings. Moreover, the embankment-driven flooding would recur annually with king tides.

However, as Hummel points out, “this is just an assessment of the alternatives available at the time.” Indeed, Highway 37 planning has evolved considerably since then, thanks partly to input from restoration practitioners who explained how the wetlands along the low-lying road work. In contrast to many tidal marshes, those along Highway 37 historically lacked channel connections to the Bay. Rather, the tides ebbed and flowed via the rivers and creeks that run into the Bay.

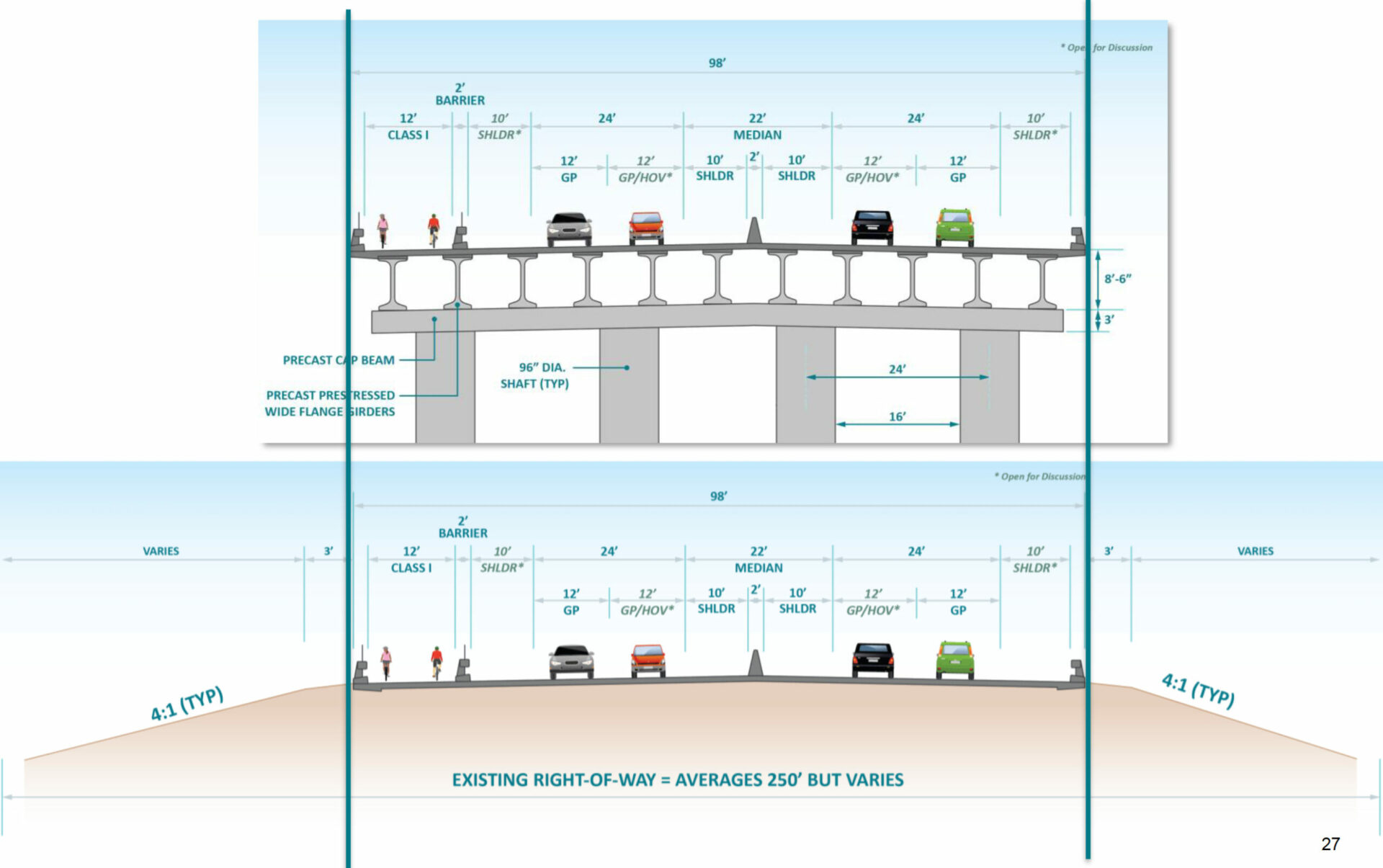

The current plan for the raised levee or embankment option is to lengthen the bridges over these waterways. “Longer bridges means wider channels for tidal flow,” Lowe says. “The embankment can’t be a continuous barrier.” For Lowe, one of the takeaways from Hummel’s work is that it supports this bridge lengthening. “It shows we dodged a bullet — longer bridges will protect San Jose,” he says.

Differences in the footprint of the new Highway, causeway versus embankment approach. ImageL TY-LIN International

Another key takeaway from Hummel’s work is that it documents the economic damages that were avoided by designing the Highway 37 embankment option to mesh with local tidal marsh ecology. “It’s important to put a value on that,” Lowe says.

Besides evolving, the range of Highway 37 options is also far broader than those proposed in 2015. Jean Finney, Caltrans deputy director for transportation planning in the Bay Area, succinctly summarizes current options as retreat, protect or accommodate. Retreat entails exploring alternate routes, such as widening inland roads or building a bridge across the Bay from Vallejo to Highway 101; protect entails keeping the Highway 37 where it is via a combination of shoring up levees and restoring tidal marshes to absorb floodwaters; and accommodate entails raising the highway on a berm or causeway.

Hummel’s work could reveal the impacts of other current Highway 37 options on the rest of the Bay, and she and Lowe are now exploring a collaboration to do just that. “We want this to be a tool that can actually be used, not just pure science,” Hummel says.

Hummel’s work has also sparked interest from Bay Area county planners eager to know whether protecting their own shores will flood neighbors near and far around the Bay. Webster is happy to hear this. “We’ve all been wondering about the impact of all these projects going up around the Bay,” she says, referring to levees and seawalls in the works in the South Bay, Foster City, and the San Francisco airport. “It’s just a big bathtub so water is just going to get pushed elsewhere.”

More:

- Hummel Study of Assessing the Influence of Shoreline Adaptation on Tidal Hydrodynamics: The Role of Shoreline Typologies in JGR Oceans

- Hummel Study of Economic Impacts of Sea Level Rise Adaptation with Hydrodynamic Feedbacks Rise in PNAS

- SF Chronicle Article on Highway 37

- Policy Committee Materials on Highway 37

- The Grand Bayway, Resilient by Design Bay Area Challenge, 2018