Delivering BART Muck to South Bay Marshes?

“It’s really hard to get dredged material delivered to the South Bay.”

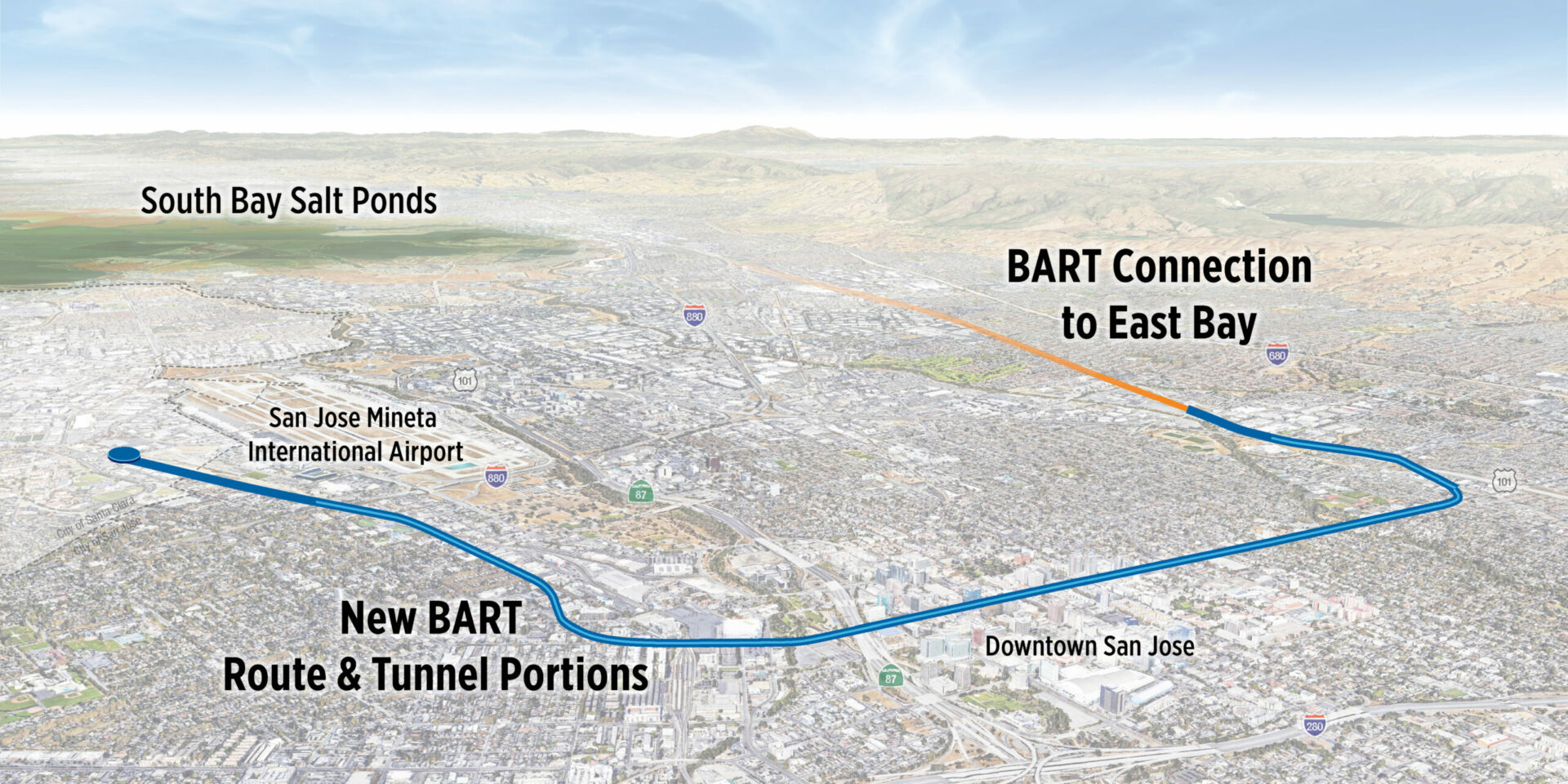

Sometime in 2025, an enormous cylindrical machine, built especially for the purpose, will begin burrowing deep beneath the streets of San Jose, creating a five-mile-long tunnel for the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority’s planned BART extension into downtown. A rotating cutter-head will dig through soil and rock; as the machine advances along its underground route, a conveyor system inside the machine will remove the excavated material and carry it back to the surface. If an innovative plan by the Valley Transportation Authority, the Coastal Conservancy and others comes to fruition, that material may help several marsh restoration projects along the South Bay shore stay ahead of climate-driven sea level rise.

“This opportunity is just huge,” says the Coastal Conservancy’s Evyan Sloane. The conservancy manages the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project, which is restoring more than 15,000 acres of former industrial salt ponds to tidal wetlands and other habitats. The conservancy hopes excavated material can help restore the salt ponds to tidal marsh much more quickly than is normally possible.

Interior of the A8 ponds group. Photo: David Halsing

Obtaining the right kind of material is one of the most problematic issues for restoration and sea level rise protection projects, particularly in the southern shallows of San Francisco Bay .

“It’s really hard to get dredged material delivered to the South Bay,” says the conservancy’s Dave Halsing. “Typically, we don’t actively raise the pond bottoms at all. We just let natural processes deliver the sediment once we’ve breached the pond,” reconnecting it to tidal action.

Material from the BART project could change that. According to VTA’s Ann Calnan, who heads the Beneficial Reuse of Excavated Material in Tidal Marsh Restoration Project, the BART excavation could produce up to 3.5 million cubic yards of so-called “tunnel muck” that could be used for restoration work.

“There’s all this material coming out of the tunnel — why not put it to good use?” asks Calnan, who says that one goal of the BART project is to be as sustainable as possible. In addition to the benefits of marsh restoration, reusing the material close to its source eliminates some of the environmental and financial cost of transporting it to landfills.

Calnan is currently preparing environmental and permitting documents for the project, which she expects will be ready for public review sometime next summer.

The conservancy hopes to use the tunnel muck in a collection of ponds known as the A8 group, located near the community of Alviso in the Don Edwards SF Bay National Wildlife Refuge, which is managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The ponds in that group, which total more than 1,400 acres, are currently five to six feet below marsh plain elevation, says Halsing. He notes that ponds that deep would take many years to fill naturally.

Halsing describes the BART material as having the consistency of toothpaste or oatmeal. “You couldn’t build anything on it, but it’s really good for filling the bottoms of these deeply subsided ponds,” he says. “We can shave decades off of the time it takes to return to tidal marsh depending on how much material goes to different ponds.”

The salt pond project is one of several restoration and flood protection projects in the Alviso area that could benefit from the tunnel muck. Although the projects are led by different agencies, there is overlap between the teams, who work closely together to coordinate activities.

Further west along the bayshore, Valley Water is partnering with the salt pond team on the Calabazas/San Tomas Aquino Creek-Marsh Connection Project. According to Valley Water’s Judy Nam, the connection project will realign the creeks, connecting the A8 group ponds and Valley Water-owned pond A4 to increase sediment delivery into the ponds.

“We made so many alterations around the landscape,” Nam says. “It’s not possible to go back to exactly how it used to be, but we’re trying to restore natural functions.” She says the primary objectives are habitat restoration and flood protection that is resilient against sea level rise, as well as reduced creek maintenance costs and enhanced public access.

Judy Nam plants a stake to establish the high water mark at Pond A4. Photo: Valley Water

Nam says her team has narrowed project alternatives down to seven, and she expects to present a preferred alternative to Valley Water’s board in the fall, with the hope of starting construction in 2028. In the meantime, she is submitting permit applications this summer on behalf of another related project, the Pond A4 Resilient Habitat Restoration Project, to begin using material dredged from the creeks to create mudflat habitat — and she is also hoping to use tunnel muck to accelerate that process.

“This could be a game changer in terms of pond bottom elevation reaching the marsh plain elevation level in the next 5 to 10 years,” Nam says.

Just east of the A8 group, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers-led South San Francisco Bay Shoreline Protection Project is building a new flood protection levee alongside several other salt ponds, including A12 and A13. When that levee is complete, the project team — which includes the Conservancy and Valley Water — will breach and restore the adjacent ponds, creating transitional habitats such as ecotones. Those two ponds have been drawn down to make the levee easier and safer to build, Halsing says. Tunnel muck could be deposited directly onto the ground before the ponds are breached and filled.

Natural sediment movement can occur through channels like Guadalupe Slough (foreground) but it won’t be enough to raise ponds like A4 in the background. Photo: David Halsing

Despite the muck reuse project’s thrilling potential, there are several not-inconsequential hurdles to clear before it becomes a reality. First and foremost is the need to confirm that the tunnel muck is safe for the environment, Calnan and Halsing note.

In order for the tunnel boring machine to work efficiently, engineers must mix the excavated dirt and rock with chemical soil conditioners, which vary in composition depending on what kind of geologic conditions the machine encounters as it moves through the earth. Calnan’s team is conducting bioassay tests on the products that might be used to ensure their safety.

“We’re doing all we can to prove or disprove that this material can go into the former salt ponds,” says Calnan, who expects the testing to be complete by September or October. “Once everybody’s satisfied [and] the material is good to go, we will be full speed ahead.”

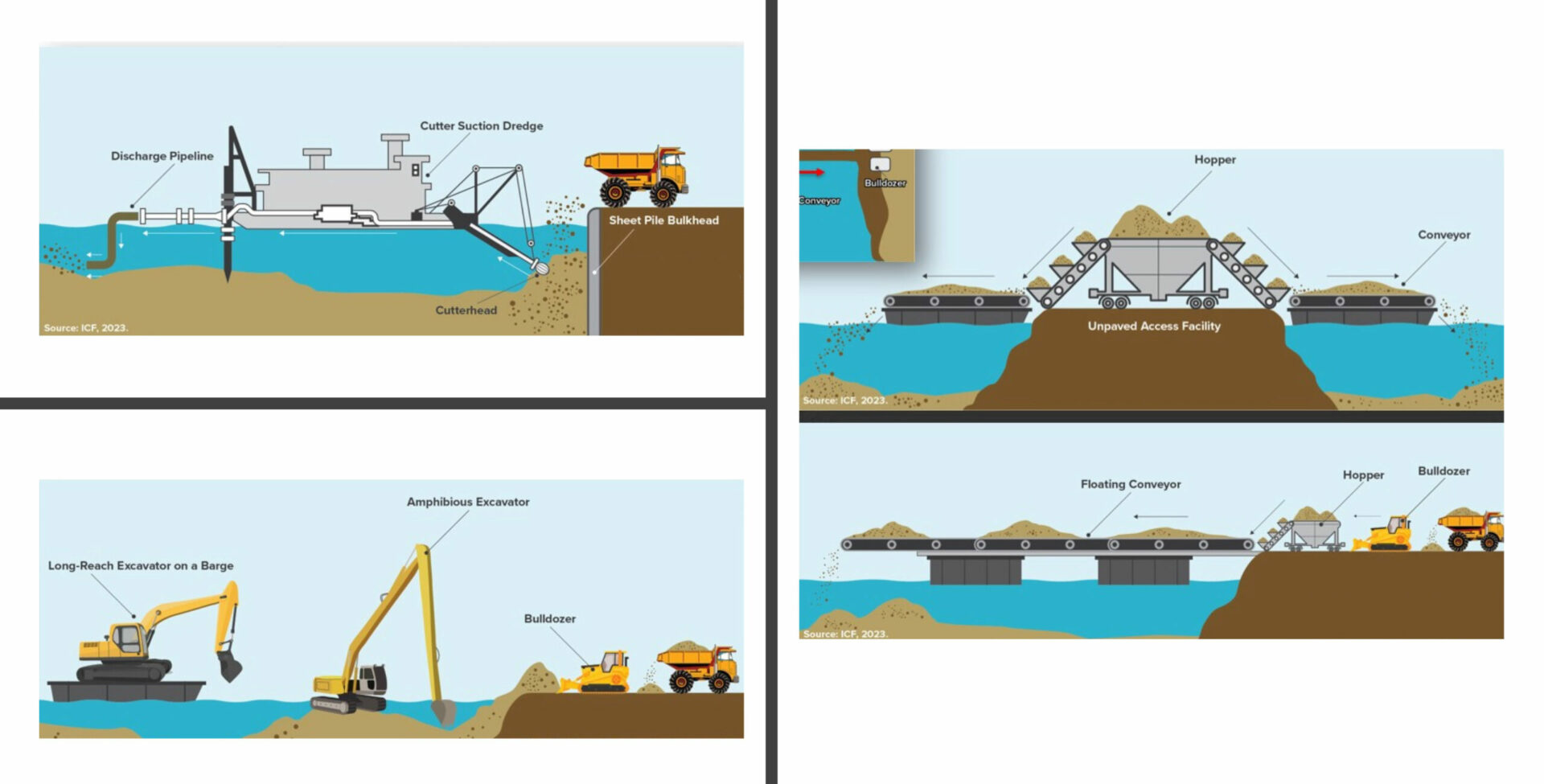

The project is also weighing the costs and benefits of different methods of transporting the muck from the tunnel to the marsh. The options include adding a spur track to the existing Union Pacific Railroad line and transporting the material by train, trucking it to the ponds — which could involve up to 25 trucks per hour — or possibly laying down a pipe to carry it directly to the marsh. Finally, the project is assessing various methods of placing the material in the ponds.

“When that muck starts coming out, we want to be ready to receive it,” says Calnan.