Crunching the Adaptation Numbers – Not Peanuts

“When people start to talk about money, I always bring up the cost of inaction.”

Back in April, the Bay Conservation and Development Commission, Metropolitan Transportation Commission and Association of Bay Area Governments made splashy headlines when they released the results of a joint study on the likely cost of protecting Bay Area shores from rising seas. But the eye-popping top-line number — approximately $110 billion — didn’t offer much insight into the practical and financial complexities of the challenge facing the region. A new inventory of adaptation projects from the same agencies, with a linked interactive map, are much more revealing,

The Shoreline Project Inventory and Map form the backbone of a new Sea Level Rise Adaptation and Investment Framework that seeks to identify near-term adaptation needs and study potential ways to fund them. The framework was previously identified as a priority by three regional planning initiatives, BCDC’s Bay Adapt Joint Platform, MTC/ABAG’s Plan Bay Area 2050, and the San Francisco Estuary Partnership’s 2022 Estuary Blueprint. As a living document, the inventory will now create a common basis for future regional plans.

The inventory comprises 192 adaptation projects, including areas where planning is underway. The costs range from $100,000 for a flood-proofing study of the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency’s Islais Creek facility to more than $8 billion to save the North Bay’s already flood-prone Highway 37. Users can also explore locations where protection is likely to be needed but where no studies or planning have been done. Crucially, more than half of the total cost — an estimated $54 billion — are projected to be in these areas.

“There is a significant gap in where we’re seeing vulnerability and where we’re seeing adaptation occurring at this moment in time,” says BCDC’s Todd Hallenbeck, who developed the inventory database and map (see charts below).

That’s the bad news. The good news is that a large number of the adaptation projects in progress are trying to optimize bang for the buck and achieve multiple benefits. “In some fashion or another, many projects are hybrids, integrating both grey and green adaptation strategies, which I think points to the value local and regional leaders are placing on multi-benefit solutions,” says Hallenbeck.

Although sea level rise is a regional challenge, the nine counties of the Bay Area are taking vastly different approaches. Some, such as Santa Clara and San Mateo, have already made impressive progress, with several large-scale shoreline protection projects planned, underway, or even completed. Others, including Alameda and Marin — the two counties looking at the biggest adaptation costs — are still identifying priorities and figuring out how to tackle them.

Despite these differences, the county profiles that follow do have some common themes, particularly when it comes to the obstacles to adaptation. In addition to the dollars that will be needed to create new infrastructure, whether grey (concrete seawalls etc.) or green (vegetated habitat, wetlands etc.), complying with regulatory requirements will add another layer of expense. Governance is also a major concern; many of the areas needing protection stretch across multiple jurisdictions, requiring coordination across city or even county lines. Likewise, the priority now placed on nature-based, socially-equitable solutions may require more initial investment but is sure to save money and reduce harm later.

“In the next two years, a whole slate of nature-based adaptation projects will be advancing, with vision from local communities, through design and permitting. We will need creative strategies to address funding, governance and permitting challenges if we want to reach the speed and scale needed to adapt to climate change,” says SF Estuary Partnership planner Heidi Nutters.

Tools for battling sea level rise range from a coastal plant called seablite and chunks of broken concrete to muscle from local communities. Photo: SFSU-EOS.

Perhaps most critically, there are real challenges in obtaining the public buy-in needed for action. In many cases, new funding mechanisms (i.e. taxes) will be needed to foot the adaptation bill (the federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act can’t pay for everything). But with the seas rising slowly enough that it’s hard to see happening on a day-to-day basis, convincing people of the urgency of adaptation is a heavy lift.

As the clock ticks and the region works to narrow priorities and pin down costs, a look at each county’s initiatives reveals the everyday challenges of adaptation. KneeDeep’s reporting team surveyed all nine counties for current projects, and explored how each will pay for it (most dollar amounts cited come from the inventory).

North Bay Counties – Highway & Last Wild Waterfront – $13 Billion

Adding up acreages and costs of sea level rise adaptations around the Bay, the usual unit is the county. In the North Bay, however, there is a shared landscape straddling Marin, Sonoma, Napa, and Solano counties that seems to need its own analysis: the western and northern shores of San Pablo Bay.

In the old days, the stretch from northern San Rafael to Vallejo was largely a salt marsh fed by local creeks and rivers, interrupted here and there by an intruding chain of hills. Even now, the arc contains two notable remnants of the Bay margin that was: the much-studied China Camp Marsh and Petaluma Marsh, the largest surviving scrap of the original Bay fringe. But these legacies are dwarfed by plans to reconnect truly vast tracts of formerly diked land to the tides, creating not only habitat but also a great sponge to absorb, and buffer against, rapid sea level rise.

The San Pablo Baylands are a sponge, too, for money. In the new regional inventory of planned and potential adaptation projects to sea level rise, the sub-region stands out both in acreage to be treated — some 55,000 acres — and in billions of dollars to be spent: over $13 billion. As a rule, it’s not the wetland work that really drives up the price tag; it’s the need to protect adjoining urban areas and, above all, key transportation arteries: rail lines and roads. Well over half the projected bill comes from the plan to elevate a vital and already threatened highway from Novato to Vallejo, California State Route 37. (See stories that follow for coverage of adaptation projects south (Marin) and west (Solano) of Route 37 and the San Pablo Baylands).

View of projected sea level rise effects on Highway 37 near the 101 interchange as of 2100. Image: CalTrans.

The San Pablo shoreline can be roughly segmented by watershed: Las Gallinas Creek in northern San Rafael; Novato Creek; the Petaluma River; Sonoma Creek; and the Napa River.

Las Gallinas is the smallest compartment. Plans call for improving habitat at county-owned McInnis Marsh and managing a larger area to the north, now private land, as “diked subsided baylands,” a label the inventory applies to much active farmland. The “green” components total some $37 million dollars in the median estimate. This sounds like big money until compared with the costs of protecting urban neighborhoods, an existing road in China Camp State Park, and—above all—a stretch of Sonoma Marin Rail Transit track (for the SMART train). Of $780 million in identified needs in this bight of bayshore, $568 million is attributed to the rail line.

North of already recovering wetlands at Hamilton Field is a considerable block along and near lower Novato Creek. The largest area, with the lowest cost, is known as the Novato Baylands Project. It envelops wetlands restoration and levee improvement around the lagoon neighborhood Bel Marin Keys, a complex wetlands management plan for what is called the Deer Island Basin (see Marin County story), and levee improvements, for a total of about $146 million. Here also are the western anchors of Route 37 and a parallel eastbound rail line, discussed separately below.

Looking south over the Petaluma River Valley, which includes both ancient and restored tidal marshes, diked pastures and transition zones. While opportunities exist to restore and connect baylands ecosystems, the SMART tracks, State Road 37, Lakeville Highway, and levees present significant barriers. Photo: Robert Janover, Courtesy Sonoma Land Trust.

Across the low chain of Black Point hills lies the Petaluma River watershed. The centerpiece here is the ancient central marsh, healthy now but threatened with drowning as sea level rises. The Petaluma River Baylands Strategy looks to protect it by giving it migration room. There is also opportunity to improve its connection to feeder streams like San Antonio Creek on the west. On the east, the plan lays out some options for deeply subsided, privately owned farmland. Including smaller adjacent projects, and ignoring roads and railroads for the moment, the cost looks like $924 million.

East of the Sears Point ridge (hiding the popular raceway) is the realm of the Sonoma Creek Baylands Strategy, the biggest single blob on the regional agencies’ map. It comprises over 18,000 acres (larger than the entire South Bay Salt Pond Restoration), most of it to be reconnected to tidal action. The former military property at Skaggs Island is the heart of it.

Consultants Steve Pye and Kate Freeman return from installing cordgrass transplants at Sears Point as part of an effort to address significant shoreline erosion from wind-wave action. To rebuild the shoreline, a team led by the Sonoma Land Trust recently anchored large logs shoreward of the bay mud to serve as wave breaks and, more effectively, as wave shadows, among other nature-based interventions. Photo: Corby Hines, Courtesy the Sonoma Land Trust.

A lengthening of a bridge over Tolay Creek, planned as part of early work on Highway 37, will help with water flows. There are not many opportunities around the Bay, says Julian Meisler of the Sonoma Land Trust, to protect entire ecosystems: “Here, we really have one.” The inventory pegs the core cost, including some related adjoining projects, at $377 million.

The map and list skip over the next zone to the east, former Cargill salt ponds now owned by the state and long since rewatered. Beyond lies the region threaded by the Napa River, from the city of Napa to the mouth at Vallejo. The already successful flood control project at Napa is on the inventory list at modest added cost for refinements. “Our flood project continues to prove to be money well spent. We had zero flooding issues in the city this winter,” says Rick Thomasser of Napa County Public Works, who says additional planned restoration projects along the river embrace climate resilience.

Several other projects in the Napa flood zone build on past efforts at modest cost; continued work at flooded Cullinan Island, part of the San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge; and the American Canyon Wetlands Restoration Project, which will expand an existing marsh restoration to 850 acres, give the marsh migration room, and add recreational features like kayak launches. These efforts account for most of the acres, but the bulk of the region’s projected $803 million adaptation bill is attributed to levees and seawalls at Vallejo. Photo (right): Jessica Davenport.

Several other projects in the Napa flood zone build on past efforts at modest cost; continued work at flooded Cullinan Island, part of the San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge; and the American Canyon Wetlands Restoration Project, which will expand an existing marsh restoration to 850 acres, give the marsh migration room, and add recreational features like kayak launches. These efforts account for most of the acres, but the bulk of the region’s projected $803 million adaptation bill is attributed to levees and seawalls at Vallejo. Photo (right): Jessica Davenport.

All of these numbers so far add up to over $3 billion, a tidy sum. But the real sticker shock comes with needed rescue of two transportation corridors threading the North Bay wetland arc: a freight railroad line now owned by Sonoma-Marin Area Rail Transit, and California’s Highway 37.

The railroad from Novato to Suisun City, though neglected of late, is coming in for attention. The draft California State Rail Plan calls for its rehabilitation as a passenger line. It parallels 37 from Novato to Sears Point and then swings north to follow generally higher ground—but not high enough to escape sea level rise. The median estimate of cost to protect it is $2.2 billion.

Then there is the road. This vital transportation corridor is often congested to impassibility; in its present configuration it also hampers water flow into the emerging wetlands to the north. After years of study, CalTrans, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, and four local transportation agencies have settled on two plans: a short-term one to widen the two-lane section between Sears Point and Vallejo, and a long-term one to raise long stretches on pilings. The interim plan is to cost some $430 million, much of which seems to be within grasp. “We are well on our way to being competitive,” says Suzanne Smith of the Sonoma County Transportation Authority. The median estimate for the completed causeway is $8 billion, the sources of which are mostly undefined. To aid in both stages, tolls will be collected, probably beginning in 2027. As waters rise and the causeway advances, the interim pavement will have to be removed.

Taking all these elements together, the region is projected to spend over $13 billion protecting and improving the shores in this subregion alone.

Solano County – Natural Protection Potential – $7 Billion

The North Bay’s Solano County has one foot in the urban Bay Area and the other in rural Sacramento Valley. It’s low-key towns like Benicia, Vallejo and Fairfield offer more affordable homes to some 450,000 county residents than other parts of region. But the southern edge of Solano County — with its wildlife refuges, bridges, and golden hills topped with windmills — borders water, leaving it wide open to the advancing Bay.

From west to east, the county waterfront sidles alongside San Pablo Bay, the Carquinez Strait, Suisun Bay, Honker Bay, and the Sacramento River at Rio Vista. Tidal waters reach into the county via large rivers and sloughs: Mare Island Strait at the Napa River, the Suisun and Montezuma sloughs, and the Sacramento River. The Suisun Marsh, the largest contiguous brackish wetland in the western United States is a watery landscape replete with private duck clubs. It covers a core portion of the county and currently serves as a natural horizontal levee. Major transportation corridors transect the county, including the flood-vulnerable Highway 37 (see Napa-Sonoma county story).

The waterfront in Vallejo, parts of Mare Island, and portions of downtown Suisun City will be the first to flood, as early as 2030. But perhaps one of the most urgent sea level rise threats is to the 116,000-acre Suisun Marsh, which is highly likely to flood and become open water, according to scientists.

Suisun Marsh currently protects a resilience hot spot, as identified in a new Greenbelt Alliance case study. Photo: Karl Nielsen.

“As increased water levels and salinity encroach, more and more of the tidal marsh will disappear, meaning that the ability of the ecosystem to mitigate erosion, absorb storm runoff, and act as a carbon sink, will drastically decrease,” says Alex Lunine of the non-profit Sustainable Solano.

“The duck clubs and wildlife areas can absorb the rise for a while, giving the Marsh value as a horizontal levee,” says UC Davis biologist Peter Moyle, a co-author of a forward-looking 2014 book on scenarios for the marsh’s future. “Much of Suisun City will need levee protection eventually unless the Suisun Marsh is managed to accommodate sea level rise. This will take some bold planning and actions.”

While not so bold yet, the county has taken the first steps to addressing threats by reaching out to interested parties. To this end, local leaders formed the Solano Bayshore Resiliency Roundtable in late 2022. Members include the Solano and Suisun Resource Conservation Districts; nonprofits such as Sustainable Solano, Greenbelt Alliance, and the Solano Land Trust; municipalities (Fairfield, Suisun City, Vallejo); Solano County; and local flood, fire, water, sewer and school districts, among others.

The group is six months old and meets monthly. An informal poll at a recent meeting suggested that roundtable members viewed adaptation needs in Solano County in this order of urgency: transportation, housing, cities, sewer service, and water supply. Protecting the Suisun Marsh rated 6th (last) on the list, highlighting the information gap many counties in the region face in communicating how natural landscapes and ecosystems can actually protect, and buffer, critical services, homes and businesses from fire and water.

“One of the things the roundtable has come together to prioritize is how we can integrate nature-based solutions and public access as part of our adaptation strategy,” says co-chair Emily Corwin, who works for the Fairfield-Suisun Sewer District. Indeed the county does have one very large nature-based solution already well on the way to completion: the 1,800-acre Montezuma Wetlands restoration project in eastern Solano ($2 million).

Crew and nieghbors working with Sustainable Solano replace a lawn with a more resilient landscape. Photo: Karl Nielsen.

While the roundtable is making progress on one important front — multi-jurisdictional collaboration — costs remain a grey area. Most expect federal and state grants to cover the biggest bills. The county already succeeded in securing an allocation of $8.6 million from the 2022 state budget to make Suisun City’s Kellogg stormwater basin and pump station more resilient. “It’s the first segment of what could become a city-wide adaptation strategy,” says Corwin.

At this point, none of the county’s cities or jurisdictions has anything resembling a sea level rise vulnerability analysis or an adaptation plan, however. It’s hard to pay attention to something that seems as far off and slow moving as sea level rise when issues like houselessness and public safety are topping the headlines, says Sustainable Solano’s Lunine.

There’s still an uphill education battle too: many more rural or agricultural landowners remain climate change skeptics; and in more urban waterfront communities, even mentioning “managed retreat” evokes disbelief. Sustainable Solano has been working to start those important conversations around climate change and flooding issues in communities around the county, and to help them take their own actions — such as food forests in front yards — to become more resilient.

“The sea level changes and extreme weather that we’re already experiencing aren’t going to wait for us,” says Corwin.

Contra Costa County – Industry & Equity – $13 Billion

Contra Costa County spans 716 square miles and has a wide-ranging diversity of land types, including most of fossil fuel refineries and producers in the region. Lots of different kinds of people live in this county, more working people perhaps that the well-to-do techies and old money prevailing on the West Bay shore. More importantly, in terms of climate change, nearly half of Contra Costa County’s border is water, sharing shores with San Pablo Bay, Suisun Bay, and parts of the Sacramento San Joaquin River Delta. Some shores are hilly, unusual for the bayshore, but small towns like Rodeo and Martinez sit right on the waterfront. All of this makes sea level rise a pressing concern for the county.

A vulnerability assessment completed by BCDC in 2016 offered an early look at the challenges. This May, Contra Costa County went so far as to approve the the creation of an ad hoc committee on sea level rise. Under this committee (funded by Measure X Climate Equity and Resilience Investment), county staff will study hard on the issue. According to the summary of the need for the ad hoc committee, “We can expect the County’s shoreline, comprised of built and natural infrastructure, to be subject to more severe and frequent flooding. The assets at risk include homes and businesses, shoreline disadvantaged/impacted communities adjacent to industrial sites, hazardous materials sites, brownfields, the US Navy’s Military Ocean Terminal at Concord, railroads, wastewater treatment facilities, electrical substations, natural gas and crude oil pipelines, prime agricultural resources, and in-Delta Legacy Communities. Contra Costa County is home to four refineries, two of which are in the process of converting their operations to process renewable fuel.”

Beyond sea level rise, county planners are also working to create a broader, well-defined climate adaptation plan considering everything from natural and constructed infrastructure improvements (such as wetland restoration, creek channel restoration, horizontal ‘living’ levees, other types of levee improvements, or sea walls) to potential land use planning changes, including modifying considerations for siting decisions and long-term strategies for shifting development patterns if necessary. They are also hoping to educate residents, special districts, property owners, and local leaders about anticipated threats and long-term commitments necessary to meet the challenge of sea level rise.

Two large restoration projects with built-in buffers to flooding and transitional habitats include Pacheco Marsh near Benicia and Giant Marsh at Point Pinole.

This past spring, when king tides and atmospheric river storms showed us future flood risk from climate change, an overflight by San Francisco Baykeeper’s monitoring drone Osprey captured flooding at a site near Pittsburg proposed for a housing development. The site includes toxic legacy contamination from a former PG&E power plant, which could be remobilized by flooding, especially if groundwater rise is added to the flood threat mix. Photo: Baykeeper.

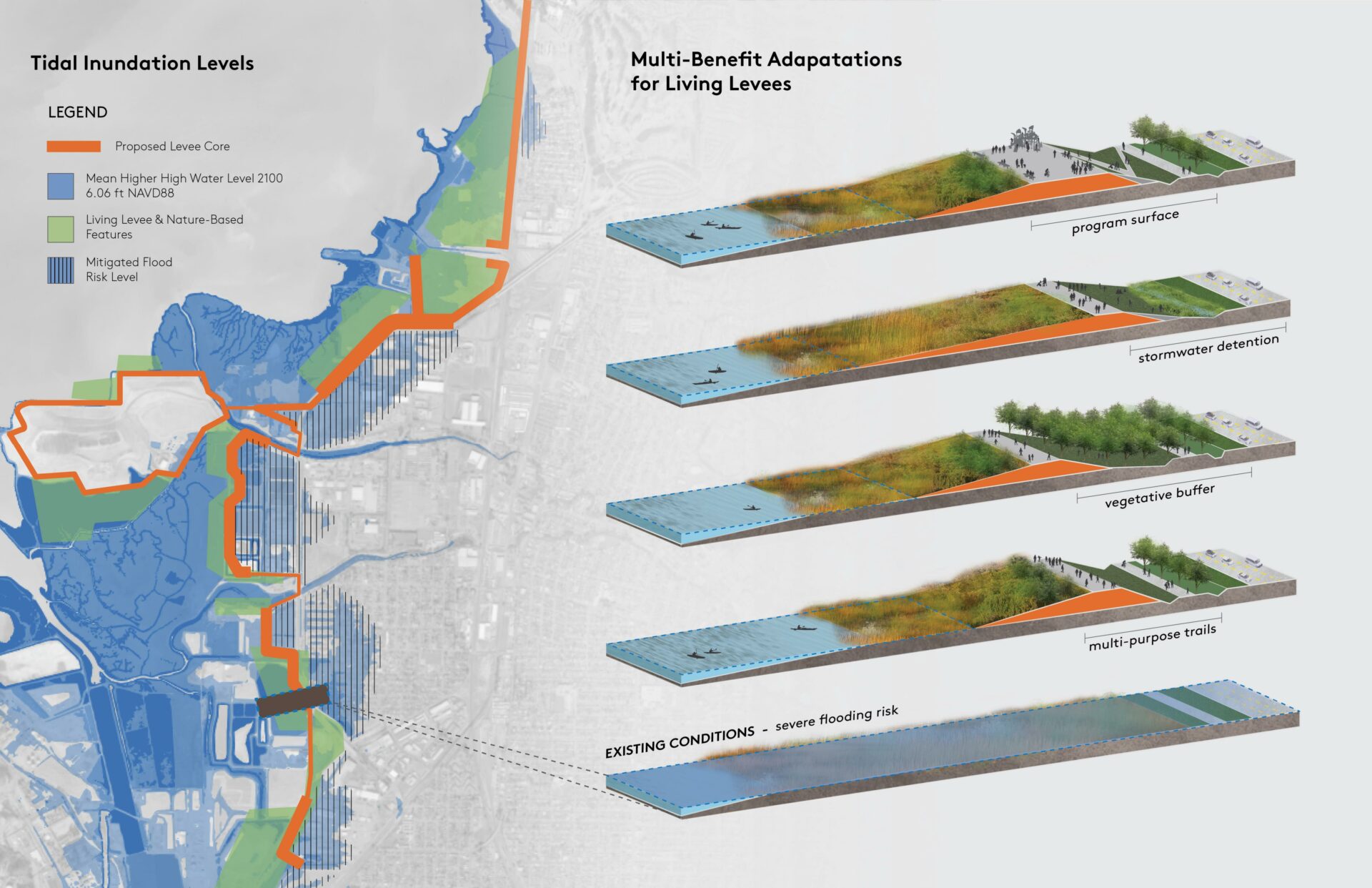

Regarding infrastructure targeting sea level rise and climate change specifically, one major infrastructure project underway is the North Richmond Living Levee. The levee is designed to both enhance wetland ecology and control flooding by creating upslope, also providing a place for native species to migrate as the shoreline changes.

As proposed, the levee is strategically designed to protect the West County Wastewater Treatment facility, as well as critical infrastructure such as the Richmond Parkway, a big highway near the coast. The Living Levee will run along the approximately 3500-foot-long western boundary of the treatment plant, providing coastal flood protection for the treatment plant through 2070. The plant services nearly 100,000 individuals and residents in Contra Costa County. The living levee project was developed with community input into the desgin vision. The project aims create local jobs and enhance trails and access to the shore.

According to Tim Mollette-Parks of Mithun, a consultant on the design team, the project has two distinct phases: the living levee, as well as a larger collaborative co-design process with the community for five miles of shoreline between Castro Cove and Dotson Marsh.

“The hope is to build relationships across the many communities, agencies and jurisdictions that play a role in the future of the shoreline,” says Mollette-Parks. That collaborative design process should be finished by fall 2023.

Vision for living levee options in North Richmond. Art: Mithun.

The project has already gotten a big financial shot in the arm from the federal government. For the Phase I Living Levee project, an authorization of $45 million for further design and implementation was included in the 2022 Water Resources Development Act, enabling the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to support the project. The project team, led by West County Wastewater, is in conversation with the Corps and elected officials to develop a future structure for the project.

The project is nothing new for Contra Costa County: a variety of government actors and local NGOs, as well as consultants, have been refining visions and community buy in for these projects for more than five years.

One issue emerging is how all these partners, organizations and residents can best work together to speed progress and manage adaptation progress in the long term.

“For the larger collaborative shoreline plan, questions about long-term governance of nature-based sea level rise adaptation are important,” says Mithun’s Mollette-Parks. “What would cross-jurisdiction and cross-agency management look like? How can community non-profits be involved, so that construction and adaptive management of the projects can create jobs in the community? What public-private partnerships might be needed on a shoreline that has dozens of privately held parcels?”

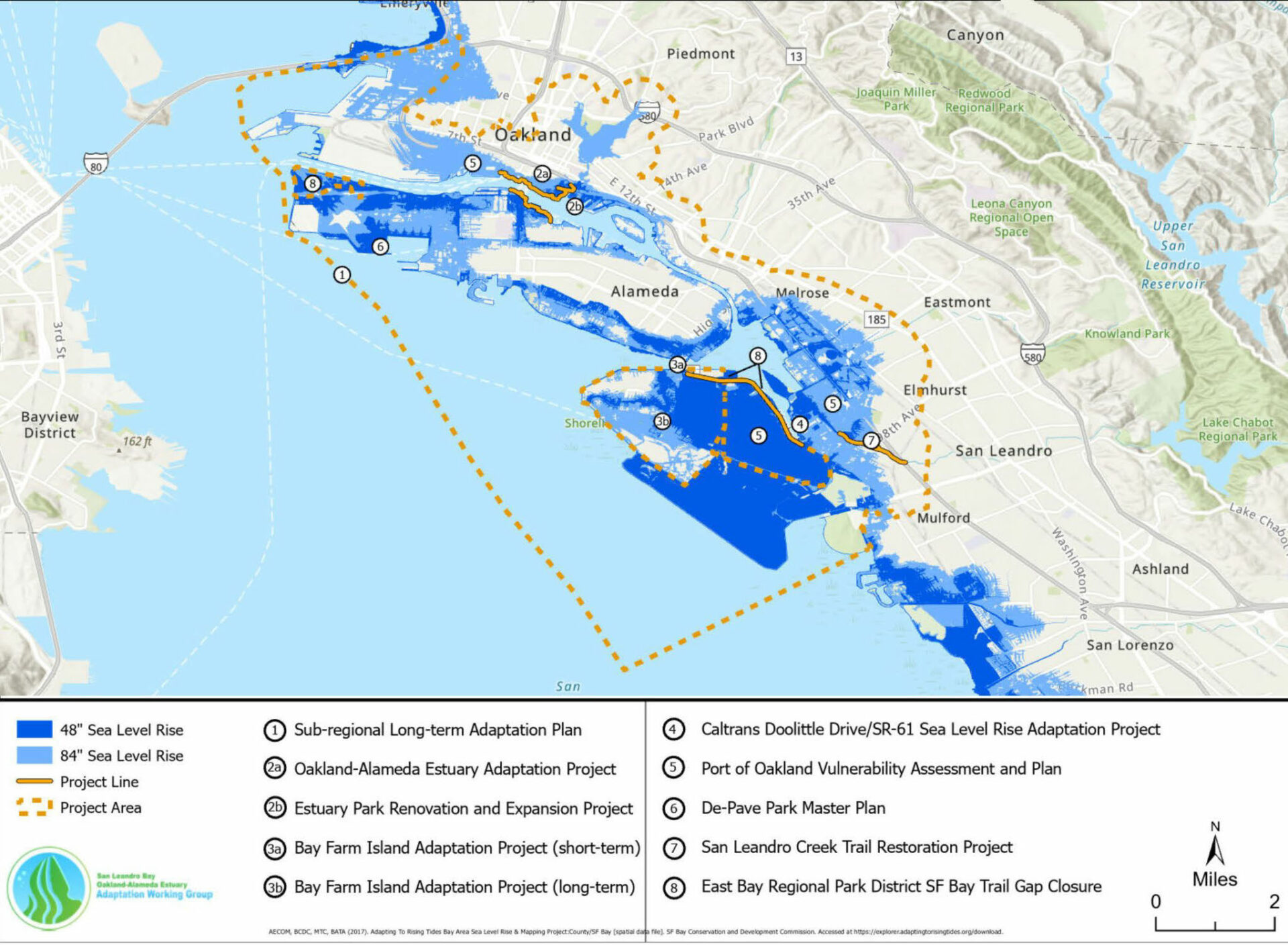

Alameda County – Lengthy Shore, Heavy Lift – $22 billion

A dense web of critical infrastructure — interstate freeways and train tracks, five bridge approaches, two tunnels, a major fuel pipeline, a world-class container port, an international airport, trucking hubs, transit stations, housing, and sensitive shoreline habitat — hug Alameda County’s lengthy shore. Interspersed with this web of mobility, which could easily be immobilized by flooding, are pockets of bayshore parkland. Indeed, the East Bay Regional Park District owns more Alameda County shoreline than any other entity. The county’s coastal geography includes low hills, flatlands, and wetlands that harbor endangered species like the salt marsh harvest mouse. Among the miles of routes, rails and trails (47 miles of Bay Trail), and the acreages of parkland, there are also brownfields and former military bases in various stages of cleanup.

“Working together as a sub-region, we can do more to adapt to the impacts of climate change than any of us can do on our own,” says the City of Alameda’s Sustainability and Resilience Manager Danielle Mieler. Mieler is leading a 30-partner working group focused on three areas of the county shore — the Oakland-Alameda Estuary, Bay Farm Island, and Alameda Island itself. “We have a ton of infrastructure, overlapping jurisdictions, and very little of the shore is the responsibility of one specific entity or another. Which is why our working group is so important.”

Sea level rise adaptation projects identified by the Oakland-Alameda working group.

The group is making progress on both short-term priorities — like fixing low spots with current flood risk at Alameda’s Veterans Court and near the Posey-Webster Tubes between Oakland and Alameda – and on a long-term adaptation plan for the entire area. “The key is a collaborative process, if we can all agree on a shared vision and needs we can make steady progress,” says Mieler.

Already the group has garnered some sizable chunks of change for their long-range planning work: $500,000 from Caltrans’ Sustainable Communities planning grants; $300,000 from the SF Estuary Partnership; $540,000 from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. For Bay Farm Island planning in particular, Representative Barbara Lee has also helped secure $1.5 million from the Congressional Community Program, matched by $500,000 from the City of Alameda’s General Fund ($323,000 of which will support local organizations rooted in the community).

While Mieler is grateful for the big pots of one-time money available for large investments from the federal infrastructure and inflation reduction bills, she says the group can only manage so much at a time. “We will need a steady pipeline over the coming years to keep up the work,” she says.

The Oakland Airport recently raised the perimeter dike for its south field to comply with FEMA requirements, then added 12 inches for sea level rise. Photo: Oakland Airport.

Some of the biggest assets to protect on the East Bay’s urbanized waterfront are of course the airport and the port, both of which trade in passengers and cargo from around the world. In 2022, the airport completed the South Field Perimeter Dike project, which addressed sea level rise and storm surge to 2050 projections for its main commercial runway, according to the Port of Oakland’s Jan Novak. The improvements cost $30 million, most of which was funded by the Port of Oakland but $6.4 million of which came from the state’s Local Levee Assistance Program.

At the port, some shipping terminals could flood in the coming decades, according to a 2019 assessment. Next steps are a more in-depth analysis of the specific vulnerabilities to sea- and groundwater-level rise on port property.

As a port climate resilience planner, Novak remains frustrated by the ongoing regulatory difficulty of using the sediment the port dredges from its shipping channels for beneficial uses like wetland restoration, levee building or shoreline protection. “Finding a way to reduce the cost of re-using our dredged material could help our sediment-starved Bay become more resilient,” Novak says.

A new state-of-the-art experiment and a forthcoming long-term plan could help move the needle on this long-standing obstacle to beneficial reuse. This September, 100,000 cubic yards of material dredged from the Redwood City harbor will be moved in scows across the Bay and placed across 138 acres of shallows off Eden Landing just south of the San Mateo bridge approach. The idea is to test “strategic sediment placement” in the water — mimicking the natural movement of sediment by waves and currents — as an option for trucking or hosing slurried material into subsided, out of the way, marshes.

“Lots of marshes need sediment now, and a boost later when the rate of sea level rise starts to accelerate, but we can’t deliver it all directly. Strategic placement can be a tool in a regional marsh maintenance plan, like a sediment sprinkler system,” says US Army Corps scientist Julie Beagle.

The experiment (a joint project of the Army Corps, the Coastal Conservancy, BCDC, the water board, USGS and others), will cost about $3.6 million, and includes covering particles of silt with a magnetic coating so they can be traced. These tracers will allow researchers like Beagle to see whether the sediment placed offshore moves onshore into marshes, as hoped.

Map courtesy USGS.

The results will help inform the array of options for delivery of sediment for beneficial reuse pre-approved by Army Corps as part of a long-term dredged material management plan Beagle is also working on for the region. “We have an opportunity to influence where all this material should go as part of the plan,” says Beagle. Matching the right material to the right places, whether a marsh or levee maintenance project, will be key to reducing the costs of adaptation in the future. “It’s tricky to optimize all these sediment-matching decisions,” says Beagle, who is nonetheless optimistic that the region can increase its rate of beneficial reuse from 30 to 100% in the not too distant future.

Sediment boosts may not only be needed by all the marshes restored in the past, but also taken into account in the marshes planned for the future, both of which will help buffer developed areas of the Alameda County shore from flooding. At Eden Landing, 2,210 acres of former salt ponds are slated for inclusion in Phase 2 ($35 million) of the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project. That effort would restore about 1,400 acres to tidal marsh and enhance about 800 acres of pond habitat. At Hayward Marsh on the regional shoreline, efforts are underway to make 848 acres more resilient to sea level rise, including relocating a least tern colony and building a gravel beach, among other plans ($20 million); at Coyote Hills near Fremont, the focus is on upland transition zones including wet meadows, seasonal wetlands, moist grasslands, coastal prairie, willow thicket, mixed riparian forest and oak savanna habitat ($19 million).

Alameda Flood Control Channel: Photo: Cris Benton

Last but not least, one can’t talk about sediment and restoration in Alameda County without mentioning Alameda Creek and the vast amounts of sediment that drain from its huge watershed into the Alameda Creek Flood Control Channel, which reaches the Bay along the southern edge of Eden Landing. For years, both local planners and international design teams have suggested redirecting that flow of sediment to the marshes so they can keep pace with sea level rise on their own — a much less costly option than maintenance dredging to keep the channel flood-ready. While the idea is still alive, jurisdictional and political obstacles continue to stall progress. “That’s our long-term hope, but in the short term, we’re working on some more modest improvements the Alameda County Flood Control District can get behind,” says David Halsing, Executive Project Manager of the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project.

“When people start to talk about money, I always bring up the cost of inaction,” says Julie Beagle.

Santa Clara County – The Silicon Shore – $8 billon

Depending on your point of view, the first things that come to mind when you think of the Santa Clara County shoreline are the campuses of tech giants like Google and the vast patchwork of former salt production ponds now being remodeled by the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project. The latter offers a natural buffer against rising sea levels that neighboring cities like Milpitas, San Jose, Santa Clara, Sunnyvale, Mountain View and Palo Alto are lucky to have, though the outlying small town of Alviso remains especially vulnerable. While the population of Santa Clara County is perceived as wealthy and techy, many areas include working class communities, particularly along creek and river banks susceptible both to flooding from intense rainfall in the watershed and to the advancing Bay.

In this county, the biggest freeways are farther from shore than they are along the San Mateo and Alameda County waterfronts, but two critical public service assets standing in the future flood zone are the region’s largest wastewater treatment plant, along with an advanced water purification plant; farther west along the shore lie the Sunnyvale and Palo Alto water treatment plants. The mouths of the Guadalupe River and Coyote Creek both drain into SF Bay here via sloughs; numerous smaller creeks also transect the bayshore, most channelized to carry floodwaters faster downstream to protect urban areas from flooding.

Scarifying and compacting the material for the South Bay’s new Shoreline Levee. Photo: USACE

Santa Clara County’s most significant sea level rise challenges are already being addressed by the Bay Area’s largest flood protection project to date: the “Shoreline Levee.” A decade or more in the making, the project will build several new bigger and bulkier levees, some conventional, and some hybrid. The latter feature green infrastructure and transitional habitat components designed, in large part, to complement the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project. The first of three phases of this federal-state-locally funded project started construction last year. Phase 1 includes five reaches and four miles of new levees, as well as restoration and natural enhancement of 2,900 acres of tidal habitats. It will cost about $263 million and protect Alviso, the San Jose-Santa Clara Regional Water Treatment Facility and other assets on the southeastern shore of the county.

The smaller but equally critical water quality treatment plant on the Palo Alto shore will be partially protected by an experimental horizontal levee, or berm, irrigated by treated wastewater to provide habitat benefits along the edge of the Harbor Marsh.

According to engineer Mark Lindley of ESA Associates, the project will be going out to bid this winter. “We expect construction to cost about $2 million including plantings and management by Save the Bay,” he says.

The project benefited from the “more streamlined permitting process for special status species at the federal level with programmatic biological opinions that have somewhat standardized necessary species protection measures,” he says. The team hopes to use an acoustic barrier fence to allow construction work near habitat during bird breeding and nesting season in certain conditions. “If we can successfully implement these measures, they will allow for more flexibility in the future in implementing sea level rise adaptation projects with the limited funding available.”

Partners discuss site for Palo Alto’s experimental berm. Photo: Diana Fu.

According to the San Francisco Estuary Partnership’s Heidi Nutters, the project will be the first horizontal levee with a wastewater treatment zone to be built along the shoreline. “The Partnership worked with the City of Palo Alto to fund design and community engagement through construction using a mix of local, state and federal funding,” she says.

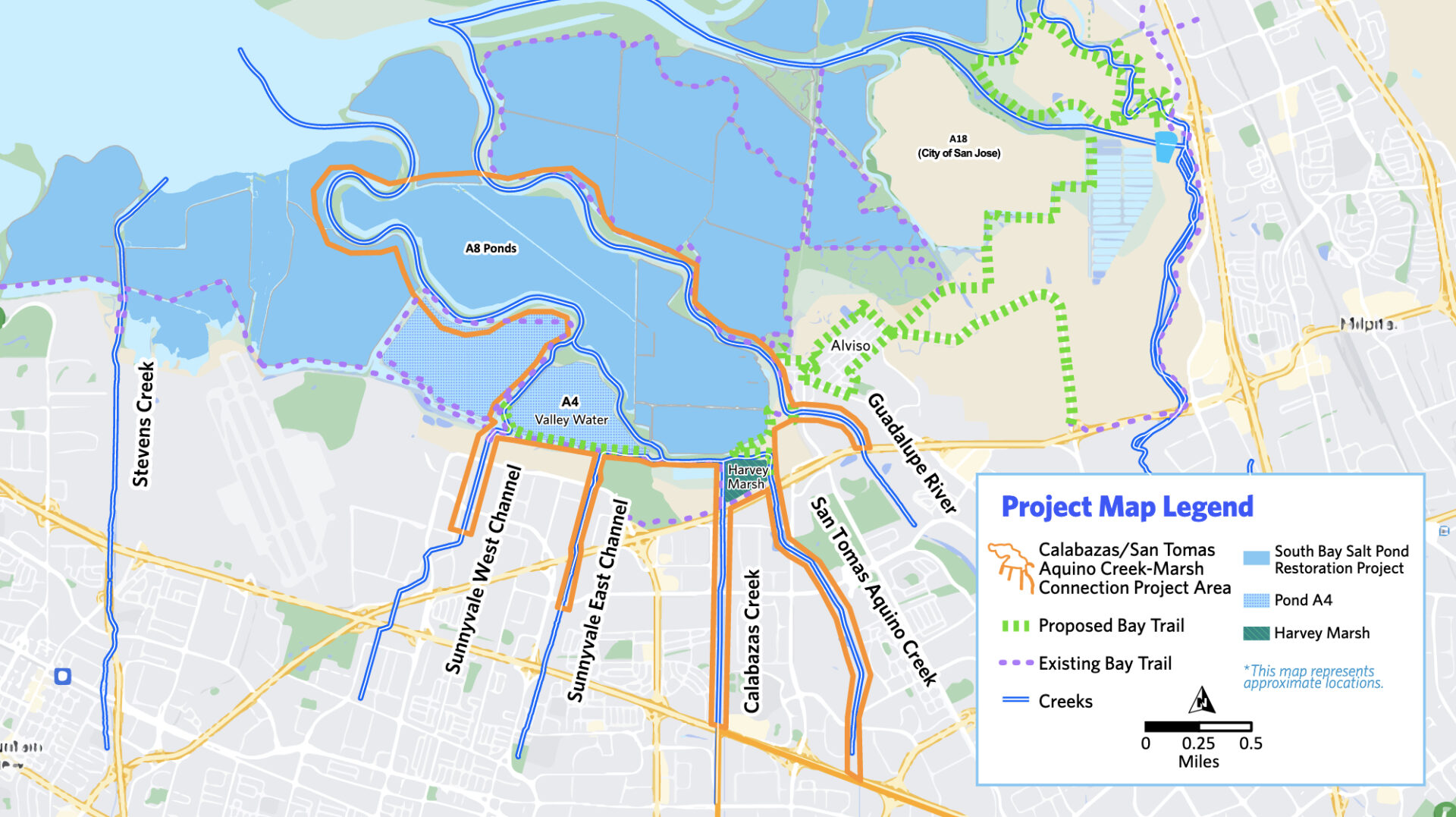

Another closely watched adaptation project near Sunnyvale, North San Jose, and Alviso will connect two creeks to Pond A8, a former salt production pond now filled with open water. The aim is to deliver much-needed sediment from the watershed to the subsided pond. Finding and transporting that many truckloads and bargefulls of sediment necessary to elevate shoreline habitats so they can keep pace with rising water levels has been an ongoing challenge for climate adaptation planners. Early research led by the San Francisco Estuary Institute, however, pointed the way by suggesting a natural source and delivery method – creeks. By reconnecting channelized or culverted creek mouths to the intertidal zone, the science argued, delivery could take place without muscle from fossil fuels.

“If nature moves sediment, we don’t have to, which saves us money,” says James Manitakos, water resource specialist for Valley Water, the agency leading the creek connection project.

The two creeks, Calabazas and San Tomas Aquino, spring from coast range headwaters and pass through earthen and concrete channels in Cupertino, Santa Clara, and San Jose, collecting enough sediment that Valley Water has to remove thousands of yards of it every year to keep water flowing freely. In the flats near the Bay, Manitakos adds, “the creeks make some right angle turns before they get to Guadalupe Slough, which is not very efficient and tends to trap sediment.”

The proposed $25 million-plus project, still in the planning stages, would straighten the creeks, and reconfigure their mouths to pass through a levee and transitional marsh into 1,500 acres of open water ponds called A8. The project is envisioned to complement existing restoration work by other agencies in the marshes. “In keeping with the sediment solutions science developed by SFEI, everyone was on board with the creek reconnection vision early, which made it much easier to deal with normal frictions of interagency collaboration,” says Manitakos.

Map: Creek reconnection vision. Map: Valley Water.

Planning for this pilot marsh-creek reconnection project is being supported by a San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority grant of $3.37 million, Prop grant from California Department of Fish and Wildlife Proposition 1 grant of $500,000; and $3.8 million U.S. EPA San Francisco Bay Water Quality Improvement Fund grant. Because the project includes environmental restoration, it will also be eligible for local parcel tax dollars under Valley Water’s Safe Clean Water Program bond (a $67 annual tax on property owners which generates about $47 million per year).

Beyond the structural efforts to protect Santa Clara County’s shore from flooding, many other climate adaptation projects are underway, in particular those that seek to help underserved communities adapt. Using Round 2 funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the county will be doing “more partnering with CBOs and empowering local jurisdictions to implement high value nature-based resilience projects,” says Jasneet Sharma of the Santa Clara County Climate Collaborative.

The biggest obstacle for this county, perhaps, is time. Like the Shoreline Levee, the creek project will likely take several years of design and permitting to get through CEQA & NEPA, and will not break ground till 2027. “Of course, we wish we could have finished yesterday,” says Valley Water’s Manitakos. Sea level rise may be slow but it’s not waiting for paperwork and funding to proceed.

San Mateo County – Lots at Stake, Leading the Way – $11 Billion

With an airport, miles of freeway, several wastewater and electrical transfer stations, a handful of tech campuses and acres of valuable wetland habitat strung along its bayshore, San Mateo County has more assets at risk from sea level rise than any in the state. It is also arguably leading the region when it comes to adaptation planning and implementation.

In 2020, state legislation created the San Mateo County Flood and Sea Level Rise Resiliency District, also known as OneShoreline, the first countywide agency in the region to address sea level rise, flooding, coastal erosion, and regional stormwater infrastructure. Working with municipalities and other agencies throughout the county, One Shoreline is advancing a number of multi-jurisdictional projects to protect several miles of bayshore, as well as a Pillar Point Harbor Area shoreline protection project on the county’s coastal side.

San Mateo County Pieces Falling Into Place from November 2022 explores several of these projects. That article also looks at plans to protect San Francisco International Airport, as well as the San Francisquito Creek Joint Powers Authority’s SAFER Bay project. The latter seeks to protect the Bay shoreline from the northern border of Menlo Park to the southern border of East Palo Alto.

Transportation routes could be cut off by flooding, such as this road in San Mateo County during a recent king tide. Photo: Len Materman.

Despite this county’s proactive approach, its adaptation plans still have some crucial gaps. In 2020 MTC and several other agencies, including the SFCJPA, released a resilience study for the area surrounding the western footprint of the Dumbarton Bridge in East Palo Alto. In addition to transportation infrastructure, the area contains homes, businesses, a PG&E substation, a fire department training facility, and Facebook headquarters, all of which are vulnerable to flooding from sea level rise. The study identified alternative approaches to protecting the area, but three years on, “there haven’t been any updates to the Dumbarton Bridge climate adaptation work,” says MTC’s Stephanie Hom. The eastern end of the bridge presents its own issues: a placeholder in the inventory identifies more than five miles of the eight-lane bridge as needing elevation, with an estimated cost nearly $7 billion.

San Francisco County – Built Up to Every Edge – $15 billion

San Francisco’s waterfront is packed. Edifices stick up and out: tall buildings, covered piers, and docks for ferries and break-bulk cargo ships. There’s Oracle Park for baseball and Chase Center for basketball, both right on the bayshore, the former so close that kayakers can catch fly balls. Around the corner from downtown rises a phalanx of new medical campuses full of high-end equipment and labs, all built in Mission Bay on squirrelly fill to 1990s specs (long before current sea and groundwater rise projections). Farther south the shore embraces the industrial shipyards of Hunter’s Point, complete with their toxic payloads, and surrounded by some very vulnerable communities already stressed by bad air, legacy toxics, and unaffordable housing. Just inland of the waterfront, but still in filled areas, lie a rabbit warren of BART and Muni Metro stations, tracks and tunnels, regional transit hubs, and landing ramps for freeways.

Photo: Port of San Francisco.

In sum, San Francisco’s shore includes a lot of expensive real estate, critical service facilities, historic districts, and current homes and businesses, and much of it comes under the wing of the Port of San Francisco. Adapting to sea level rise here, with earthquakes also in the mix, will be a very tall order requiring very deep pockets.

“There will be some big costs to protecting San Francisco residents and critical infrastructure like MUNI and the combined sewer system. Both City staff and the Army Corps want to be efficient with federal and local dollars,” says Brad Benson, the Port of San Francisco’s Waterfront Resilience Program director.

Since 2018, the Port of San Francisco has been working with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to conduct a massive research study, investigating how best to protect the City’s 7.5-mile waterfront from sea level rise, earthquakes, and king tides. The study covers the Embarcadero, the Bayview (including the low-lying Islais Creek), and Mission Bay, each with its own unique set of vulnerabilities and often aging infrastructure.

Embarcadero waterfront in downtown San Francisco. Photo: SF Public Works.

Indeed the 100-year-old Embarcadero Seawall already protecting downtown and the Embarcadero (a below-ground bulwark mostly invisible from the sidewalk) needs a major update. Making things even more expensive to protect, many areas beyond this bulwark, including parts of Mission Bay and downtown San Francisco, stand on landfill not designed to hold more weight; the Port would have to first stabilize the ground before building seawalls on top of them. And different flood hazards counterbalance each other in an interesting way: while raising the shoreline prevents coastal flooding, it also exacerbates inland flooding during storms. Because stormwater would no longer discharge from the street level, the City would have to build pumps or other forms of mechanical drainage, adding another expenditure to the project.

With billions of dollars on the line, costs are top of mind. To that end, the Port created seven different response strategies for the Army Corps to model, compare, and integrate, and the Corps has been receptive to aspects of the more aggressive interventions. Benson notes that even federal agencies are moving beyond simpler cost-benefit analyses, like the effect of disasters on the nation’s economy, towards more complex “comprehensive benefits” plans that take into account regional economic effects, environmental effects and social impact.

“The Army Corps operates at a very high level, evaluating where to make national investments in infrastructure, and leaves details about design for later in the process,” says Benson. “On our end, to prepare for the next planning phase here in SF, we want to explore what interesting things locals are doing vis-a-vis engineering with nature, managing inland stormwater risk, groundwater rise and mobilizing contaminants.”

Teams from the Port and the Army Corps meet to discuss comprehensive benefits in the SF Waterfront Coastal Flood Study this June. Photo: USACE.

Green engineers and urban planners are conducting their own experiments so that when the funding is released, they’ll have novel solutions to these trickily interconnected systems ready to go. At Mission Rock on 3rd Street, the SF Department of Public Works and the Port are testing a “balanced fill” approach to the shoreline, replacing layers of weak soil with materials that are both sturdier and lighter – which stabilizes the ground while creating higher elevation. And local jurisdictions are continuing to develop projects that’ll provide more immediate resilience to coastal hazards. The state just granted $650,000 to the San Francisco Planning Department towards adaptation in the Yosemite Slough area near Candlestick Point. San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority funds are helping the Port experiment with resilient beaches in already eroding areas at Heron’s Head near Hunter’s Point; and the Smithsonian is testing eco-friendly tiled seawalls near the Ferry Building.

For federal-local partnerships, the federal government typically pays 65% of the share; the local sponsor pays 35%, though some of the Port’s local considerations may drive San Francisco’s share upwards, according to Benson. In particular, the Port is prioritizing social equity, advocating for solutions that help the communities situated in the floodplain of Mission Bay and the Bayview. The Third Street corridor and the Creek Bridge light rail are particularly isolated, and studies show that SF’s black residents are significantly overrepresented in areas vulnerable to mid-century sea level rise.

Benson feels San Francisco and the Corps have reached an important point in the work that should result in a “tentative selected plan” by fall 2023. After public comment and regulatory agency feedback, the Corps will reach the “Agency Decision” milestone in 2024, and then send a recommendation to Congress at the end of 2025. After that, there’s a two-step federal process before funding gets released.

Despite the long timeline, Benson wants San Francisco locals to feel a sense of optimism: “I want residents to know that they’re living in a jurisdiction that’s committed to addressing these problems. Federal planning is complicated and takes a while to implement, sometimes you need multiple acts of Congress to move a project along. But I want all of us around the Bay Area, and on the West Coast, to feel a sense of urgency – after we secure funding, there’s actually a relatively short lead time to start building projects.”

Marin County – Double Trouble with Two Coasts – $17 billion

Marin County in northern California is known for having some of the most beautiful views in the Bay Area. A small county with a scenic shoreline and plentiful natural areas, Marin has about 70 miles of ocean coast and 40 miles of bay shoreline, with a unique combination of beaches, bays, estuaries, and rocky headlands. East Marin is the most urbanized, with residential and commercial areas concentrated along Highway 101 and San Francisco Bay. Industries like cement manufacturing and rock quarrying are focused in San Rafael and Novato, while Sausalito boasts several boatyards and marinas. Marin contains several publicly owned sewage treatment centers, including the Sewerage Agency of Southern Marin, Central Marin Sanitation Agency, and Novato Sanitary District. West Marin is more rural and consists mostly of agricultural land, while Tomales consists of small towns and wastewater treatment plants along the coast.

Unfortunately, there is a price to pay for Marin’s coveted views, and it’s not just the high cost of living. Most of Marin’s critical infrastructure, like roadways and utilities, are concentrated along the bay shore at low elevation. This makes Marin one of the Bay Area’s most vulnerable counties to sea level rise. With so many miles of shoreline to adapt and a short timeline, adaptation costs will be steep, even for this affluent county. The Bay Conservation and Development Commission estimates Marin’s adaptation costs at $17 billion.

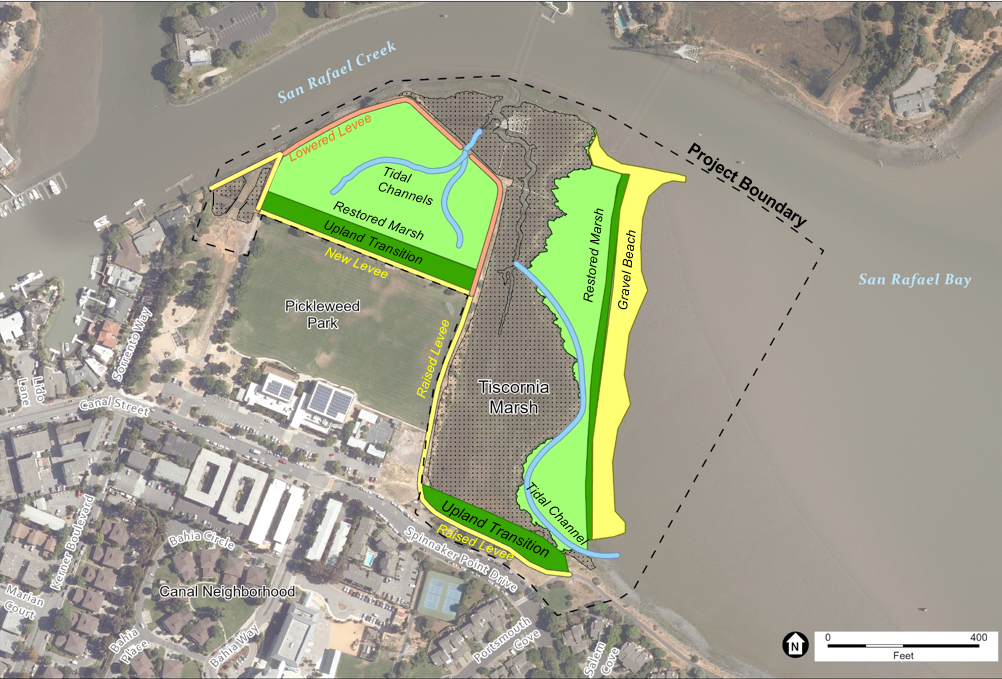

Plans for the Tiscornia Marsh project, adapting areas along the San Rafael Canal to sea level rise. Art: ESA.

One of Marin’s most challenging features is that many of its urban areas were built on wetlands, along creek channels or on the reclaimed shores of the San Rafael Canal. “The communities that were built long ago did not account for sea level rise and therefore lack the infrastructure necessary to handle the impacts that we are starting to experience,” explains Julian Kaelon, public information officer for Marin Public Works.

Another complicating factor in Marin’s adaptation process is coordinating with landowners. Much of Marin’s Bay shoreline is controlled by private property owners, and it can be difficult to get property owners to cooperate with adaptation projects. “Sea level rise and related flooding do not stop at jurisdictional boundaries,” Kaelon says. Private property owners must “get on the same page to deliver holistic solutions to the issues we are facing”.

Although the county’s adaptation needs are complex, Marin has the advantage of several years of adaptation planning under its belt. For eight years, the Marin Department of Public Works has led adaptation planning for Marin’s bay shoreline (BayWAVE) and the Marin Community Development Agency for the ocean coast (C-SMART). Both agencies have completed detailed vulnerability assessments and adaptation reports. Community-focused planning efforts have recently begun in communities like the San Rafael Canal district, Marin City, and Stinson Beach. Marin was also the first county in California to pilot living shorelines, starting with the Aramburu Island Restoration Project and the San Rafael Living Shoreline Project in 2012. Besides these projects, however, implementation of the adaptation ideas suggested in the BayWAVE and C-SMART reports has been slow in coming. While some projects are in progress, most are still in early stages of planning or design. The majority of planned adaptation projects are located in East Marin, along the more densely-populated bay shoreline, with only a few planned on the ocean coast.

One factor slowing down progress could be the difficulty in finding solutions that communities will accept. In Corte Madera, for example, a draft of the Climate Adaptation Plan was posted for public comment and the communities of Marina Village and Mariner Cove objected to one of the proposed solutions: a levee that could block the ocean view of bayside properties and negatively impact the tidal marshes. These residents also didn’t like that the plan mentioned “managed retreat.” In response to community feedback, Corte Madera released an Adaptation Assessment in 2021 which didn’t include any proposed solutions for the two communities. Later this year, Corte Madera is planning to conduct a survey that will “reengage with the bayside communities and pick up where the Adaptation Assessment left off”, according to Climate Action and Adaptation Coordinator Phoebe Goulden.

Bolinas lagoon. Photo: Marin County Parks.

Marin County also needs to make plans for adaptation on its Pacific coast. Near the small coastal town of Bolinas at the mouth of a lagoon, the Wye Wetlands Resiliency Project showcases one adaptation project close to implementation. Like many of the other planned projects in Marin, Wye Wetlands focuses on wetland restoration as a natural defense against sea level rise. Bolinas Lagoon is a tidal estuary with a rich diversity of wildlife, including species like the endangered California Black Rail, and is designated as one of the Ramsar Wetlands Of International Importance.

The Wye Wetlands Resiliency project will restore normal wetland processes disrupted by human development, reconnect Lewis Gulch Creek to its historic floodplain, elevate parts of Olema Bolinas Road to reduce flooding, and build a bridge to allow the creek to pass underneath and flow into the lagoon. After a lengthy planning process that began in 2017, the project is currently near the end of its final design stage. Construction could begin as early as summer 2024.

A patchwork of funding is covering this $2 million necessary for design and permitting. Project, and the $8 million for implementation. So far the County of Marin has allocated money from Measure A and the American Rescue Act for construction. The hope is that three grants, currently pending approval, will cover the rest of the cost and come from: the National Coastal Wetland Conservation Program ($814,000), Coastal Conservancy ($710,000), and National Fish and Wildlife Foundation ($3.67 million). Project managers will also be applying for a Wildlife Conservation Board grant to help pay for the removal of invasive species for five years.

Deer Island. Photo: Marin Sanitary.

A few similar wetland restoration/adaptation projects have also begun to move forward in Marin. By early 2024,planners will complete design and compliance work for the Deer Island Basin, near the Novato Creek Sanitary District plant. Led by the Marin County Flood Control District, this project is expected to cost $10 million, although only $1 million of American Rescue Plan Act funds have been secured. In Mill Valley, the Bothin Marsh Evolving Shorelines project will reroute and elevate the Bay Trail to reduce flooding and allow water and sediment to flow between the marsh and Richardson Bay. Marin County Parks is leading this project. The planning and design phase will cost $2 million, with $1 million already funded by Measure A, One Tam, Marin Community Foundation, State Coastal Conservancy, and the San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority. Additional planned adaptation projects that include experimental nature-based approaches are Greenwood Bay Beach in Tiburon and Tiscornia Marsh in San Rafael.

The Sea Level Rise Funding and Investment Framework, scheduled to be released this July, explores existing local, state and federal funding resources and identifies a gap of approximately $105 billion between what exists and what will be needed. The report also delves into potential revenue measures that could be explored to try to narrow that gap. (One potential revenue source, the climate resilience bond state lawmakers are drafting for the November 2024 ballot — the largest ever — would provide $15 billion statewide).

Exacerbating the funding gap is a leadership gap, says BCDC’s Assistant Planning Director for Climate Adaptation Dana Brechwald. “We need coordinated advocacy that allows us to piece together funding and then distribute it based on some prioritization,” she says, noting that BCDC itself is a regulatory agency, not a funding or advocacy agency. “There’s a lot of conversation about who could potentially [fill that role], or is it a new entity? That’s the next big question.”

This story was co-reported by Ayla Burnett (Alameda), Justin Lai (San Francisco), John Hart (North Bay counties), Aleta George (Solano), Isabella Eclipse (Marin), Daniel McGlynn (Contra Costa), and Ariel Rubissow Okamoto (Santa Clara & Alameda).

KneeDeep updated the story on July 18, 2023 to reflect new North Bay county content.

Photo: Ariel R Okamoto.

More

REGION

- Sea Level Rise Adaptation Funding and Investment Framework

- Framework Shoreline Project Inventory Map

- Inventory Spreadsheet

- Bay-Adapt – Regional Strategy for Rising Bay

- Bay Area Resilience Hotspots Greenbelt Alliance

Three Regionwide Benchmarks

- 2020 Bay Area Wide Adaptation Review, Estuary News

- 2018 Resilient by Design Bay Area Challenge, Estuary News

- 2017 Prepping for Sea Level Rise, Estuary News

COUNTIES

- Sonoma & Napa Counties

- Solano County

- Contra Costa County

- Alameda County

- Santa Clara County

- San Mateo County

- San Francisco County

- Marin County