Cruising the San Pablo Spine — A Green Streets Test Lab

“Part of the project goal was to act as a demonstration — to give the public a vision of what green infrastructure could look like.”

From tattoo parlors to senior housing, and ethnic-food vendors to world-famous record shops, it’s been said that if you can’t find what you’re looking for on San Pablo Avenue, then it doesn’t exist.

And now, the busy thoroughfare, which runs north-south through the heart of the East Bay, is also a testbed for a distributed network of rain gardens. The project, known as the San Pablo Avenue Green Stormwater “SPINE”, began nearly ten years ago (the caps are used for emphasis, not as an acronym). In the fall of 2012, the U.S. EPA issued a $307,000 portion of a larger green-infrastructure grant for the design of seven garden sites in seven different cities. Over the past decade the project has grown in cost and shrunk in footprint, and it was eventually implemented because of the persistent efforts of stakeholders including city building-permit offices, local businesses, utility districts, state regulators, and private real estate developers.

Throughout the decade of its arc from idea to tangible infrastructure, Josh Bradt, watershed specialist and project manager for the San Francisco Estuary Partnership, wrangled all aspects of the endeavor. “The selling point at the beginning,” Bradt says, “was that San Pablo Avenue, which is already a super built-out thoroughfare, could be used as a unifying factor.” It’s the thing that connects the networked nodes of rain gardens.

A Distributed System

It’s likely that what we know as San Pablo Avenue was always a major transportation corridor. The route through the flats of the East Bay probably began as a footpath, and over time grew and changed and developed like the cities that it transects. Today, San Pablo stretches from Hercules in the north to downtown Oakland in the south. The heart of San Pablo Avenue is a roughly 7.3-mile section, also designated as California State Route 123, that runs from where it crosses under I-80 in Richmond to where it crosses under I-580 on the Oakland/Emeryville border. This long and straight people-moving artery is almost entirely encased in concrete and asphalt.

When the San Francisco Estuary Partnership first pitched the SPINE, the idea was to figure out if it was possible to soften some of the hard spots. Through design and some strategic reconfiguring, the goal was to add rain gardens where stormwater could flow, collect, and be filtered on-site before joining up with the traditional stormwater drainage system. At the same time, these gardens can act like islands of soft green in a landscape of hard concrete.

“Part of the project goal was to act as a demonstration — to give the public a vision of what green infrastructure could look like,” says Brandon Davis, executive vice president of Wilsey Ham, the civil engineering firm that oversaw construction of the SPINE project. “The biggest challenge is that the area is fully developed. None of this stuff fits perfectly. So it became a long process for selecting the sites, and then peeling back the street to find all kinds of utilities and facilities under the ground. The sites also needed to be at low points to collect stormwater.”

The construction of the SPINE project was funded in part by $1.8 million in mitigation money from CalTrans to offset all of the paving required for the construction of the new Bay Bridge. Ideally, green infrastructure is built in a way that it treats runoff from a new project, but a bridge is suspended in air, making the treatment of runoff more complicated, which is why CalTrans needed the nearby green infrastructure projects along San Pablo Avenue as a means of mitigation. Additionally, the Department of Water Resources supported the project with a grant of $2.15 million, and the California Natural Resources Agency added $515,000 in construction costs for El Cerrito specifically. Individual cities around the Bay, each of which must adhere to the conditions of a regional stormwater discharge permit, also pitched in.

Since the days of the California Gold Rush, the killer combo of topography, rain cycle, urban density, and legacy pollution made the Bay a perfect collection point for heavy metals like mercury and other bioaccumulating toxins. In the last decade, state water quality regulators have been pushing the cities that ring the Bay to use more green infrastructure to help capture this noxious runoff. By collecting, filtering, and treating it before the long-lingering pollution can fully wend through the watershed, the overall ecosystem — including the wildlife and people living nearby — gets a better chance at staying healthy.

“Green infrastructure can help combat the effects of climate change and biodiversity loss,” says Kevin Robert Perry, a landscape architect and the San Pablo SPINE project’s designer. “When we can remove excessive paved surface and replace it with trees and drought or wet tolerant plants, we are able to better manage rainfall and extreme heat events. Lastly, green infrastructure helps define the character and beauty of our public space, and can make our streets more comfortable, enjoyable, and safer to walk, ride, scoot, or drive.”

What Happens Underground

Despite the obvious environmental benefits, actually building such projects in a developed urban environment is like trying to pack more sweaters into an already full suitcase.

For the SPINE, one of the biggest issues was dealing with all the existing utility infrastructure already in the ground — mainly gas lines. The Richmond site was abandoned because, according to Davis, it would have cost $1,000 per foot to move 300 feet of gas line.

Building the gardens requires room underground. To help with absorption, 18 to 36 inches of the East Bay’s naturally clay-like soil is removed. A perforated pipe is connected to the traditional stormwater system. This pipe is designed to allow water to percolate through, but leave the other material behind. It is embedded in bioretention media — a kind of special soil that will snag heavy metals and other pollutants in the runoff. On top of that is a layer of soil that is designed to allow five inches of water to move through per hour during heavy storm events — that’s the optimal time needed to get the water cleaned up.

Building the gardens requires room underground. To help with absorption, 18 to 36 inches of the East Bay’s naturally clay-like soil is removed. A perforated pipe is connected to the traditional stormwater system. This pipe is designed to allow water to percolate through, but leave the other material behind. It is embedded in bioretention media — a kind of special soil that will snag heavy metals and other pollutants in the runoff. On top of that is a layer of soil that is designed to allow five inches of water to move through per hour during heavy storm events — that’s the optimal time needed to get the water cleaned up.

Once built, all of the SPINE’s rain gardens have a similar look on the surface — the plants are all about the same age and size, and they share the common trait of being hard to kill (commonly used species include California buckeye and Persian ironwood trees). But each city and site had its own vision, priorities, and constraints.

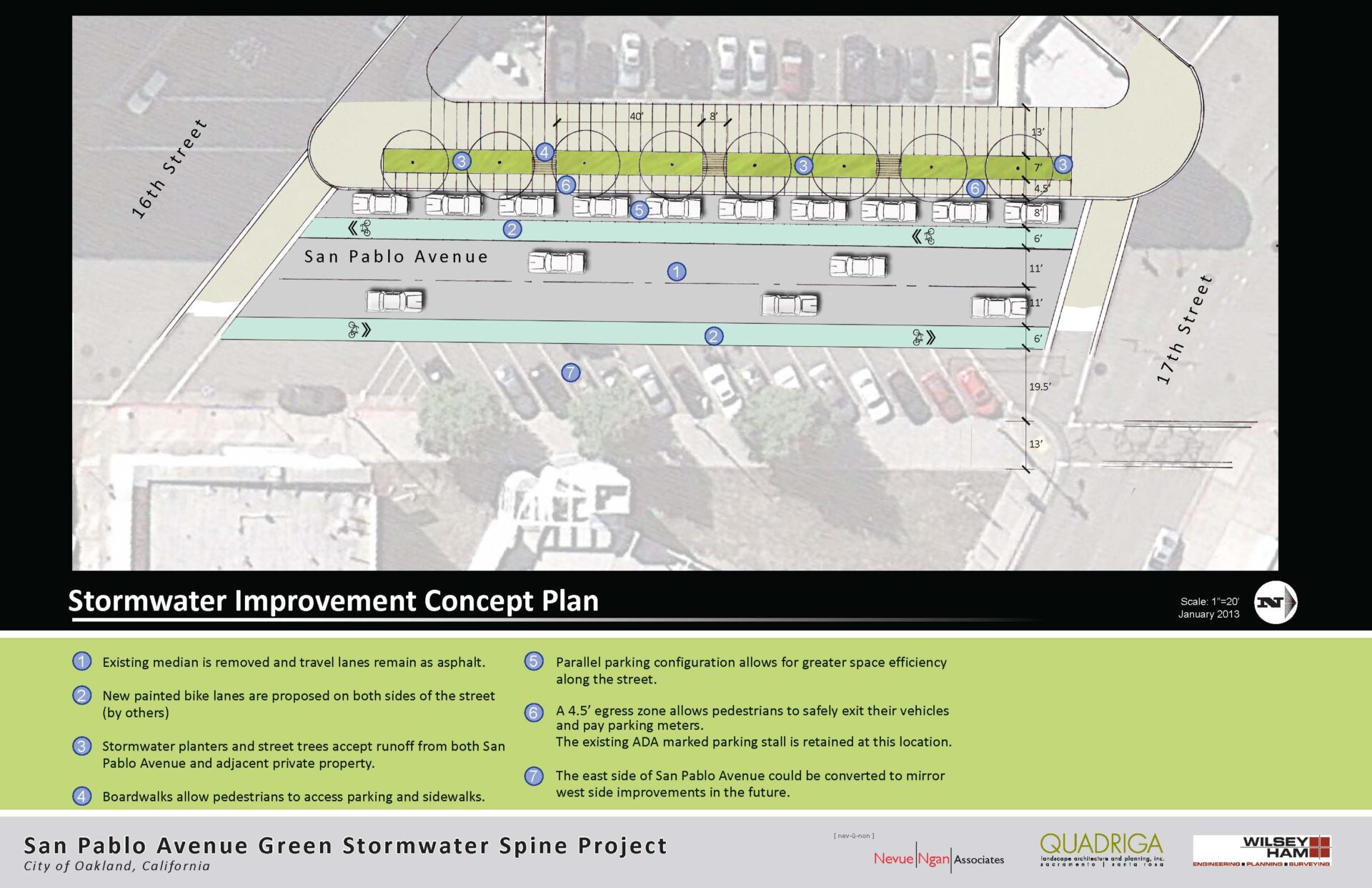

Engineering drawing for Berkeley green street. Design: Wilsey-Ham.

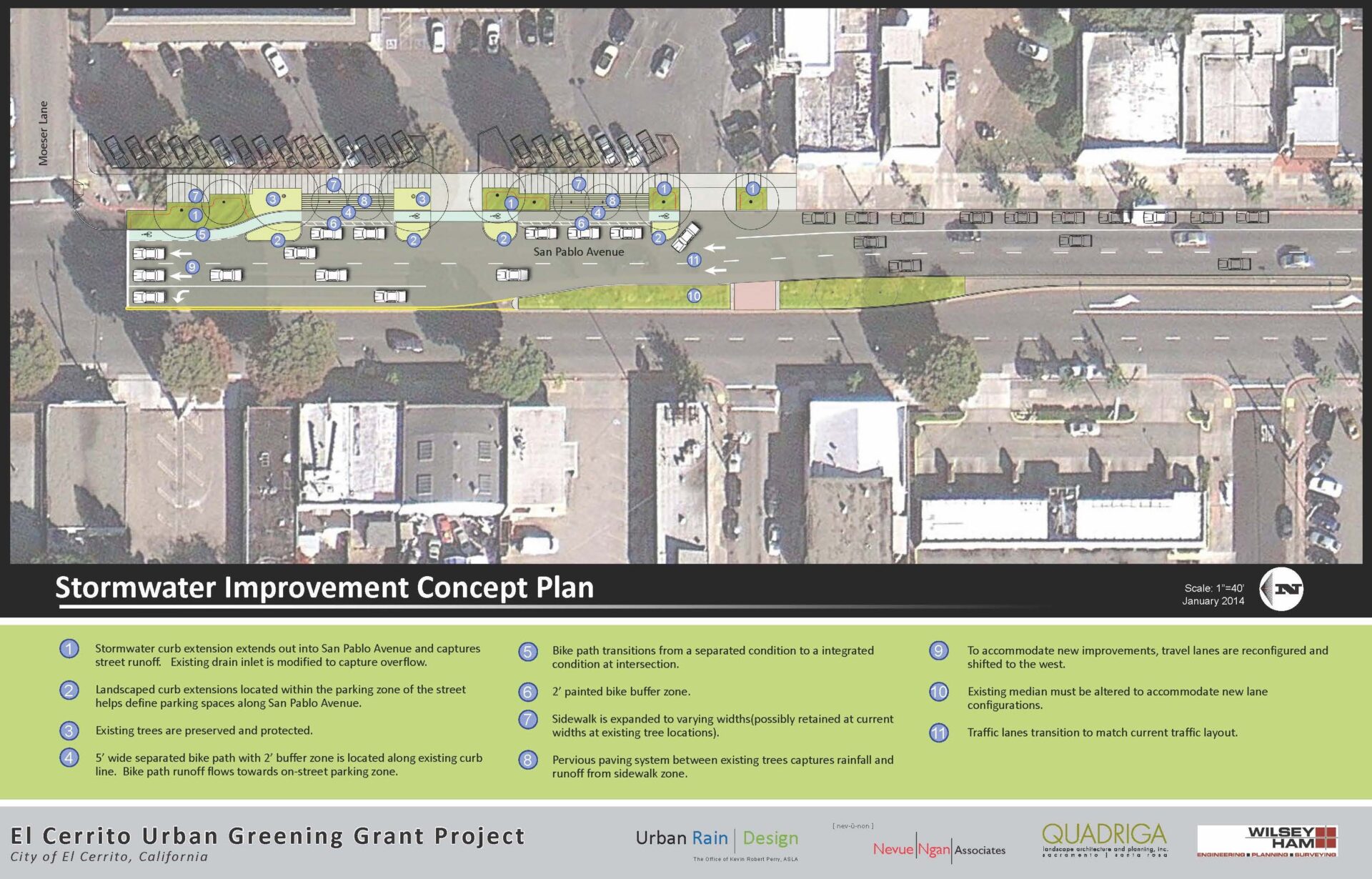

Complete Streets for El Cerrito

Corner of Moeser Lane and San Pablo

Like many cities in the Bay Area, El Cerrito has a vision for what it wants to look like in the future. This includes more bike and pedestrian infrastructure connecting its two BART stations to the surrounding homes and shops that define the community. The SPINE project’s designer, Kevin Robert Perry, puts it this way: “El Cerrito looked at how we can overlay enhanced bike and pedestrian infrastructure (complete streets) with green infrastructure. For this location, the eastbound bike lane is protected, separated from vehicle traffic using a stormwater planter, and there is also a landscape strip that separates pedestrians from bike travel. It is only a one-block study, but it showcases how many busy arterial streets can be reimagined for better overall mobility and urban greening.”

Click to see enlarged slideshow.

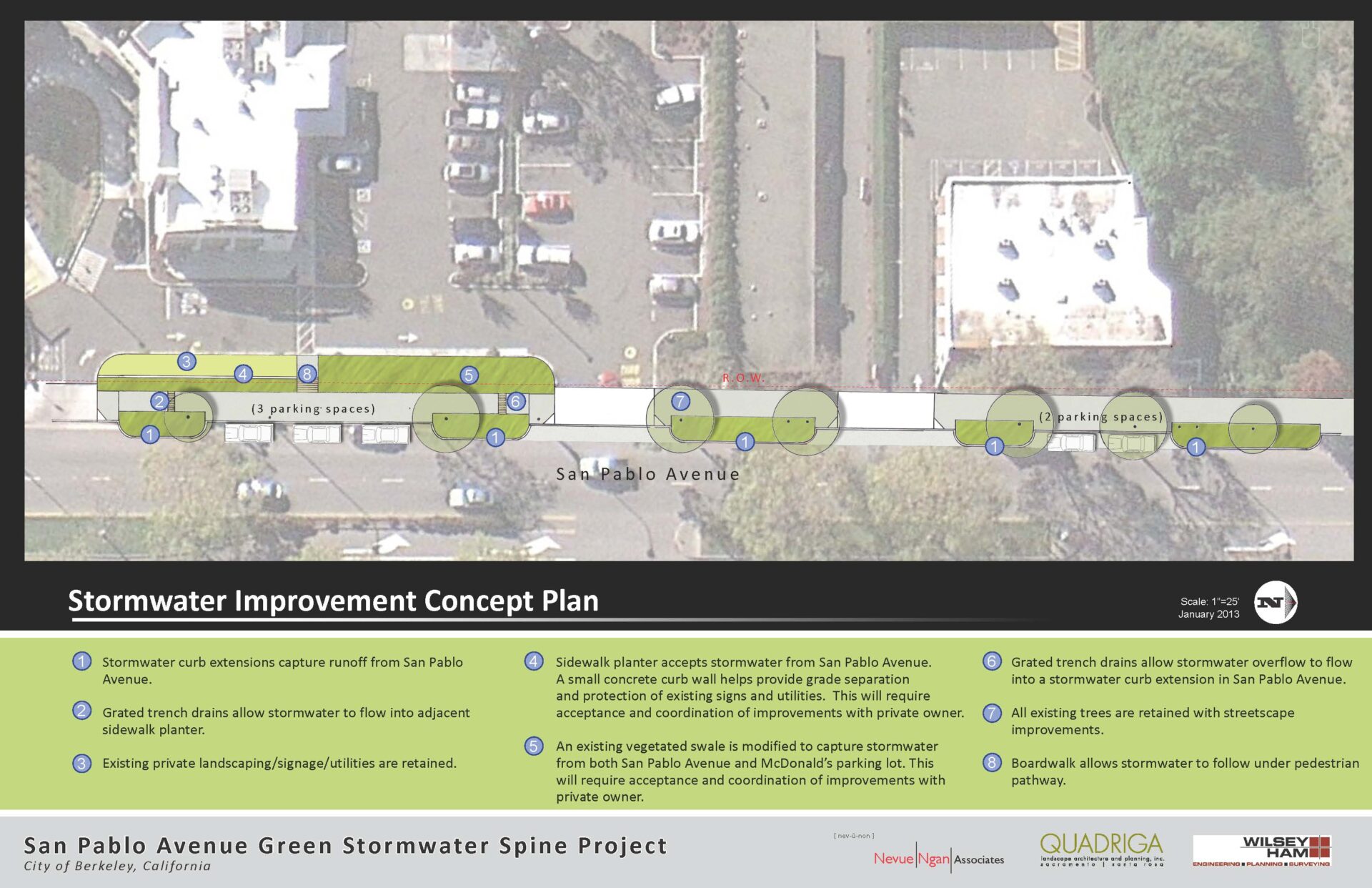

McDonalds as Magnet in Berkeley

Corner of Harrison and San Pablo

The Berkeley location is right in front of an always-busy McDonald’s. At first glance, the location seems like an odd place for a demonstration project that has “place-making” as one of its fundamental goals. But on closer look, because of its proximity to where Codornices Creek comes above ground again (it flows through a culvert for a few blocks on the east side of San Pablo and is daylighted on the west side), having green infrastructure at this location does make sense — and if nothing else it helps draw attention to the otherwise easily overlooked watershed.

According to the project’s designer, Kevin Robert Perry, “This site uses a series of stormwater curb extensions to capture stormwater runoff. The primary consideration was balancing parking loss as well as preserving existing mature trees.”

Click to see enlarged slideshow.

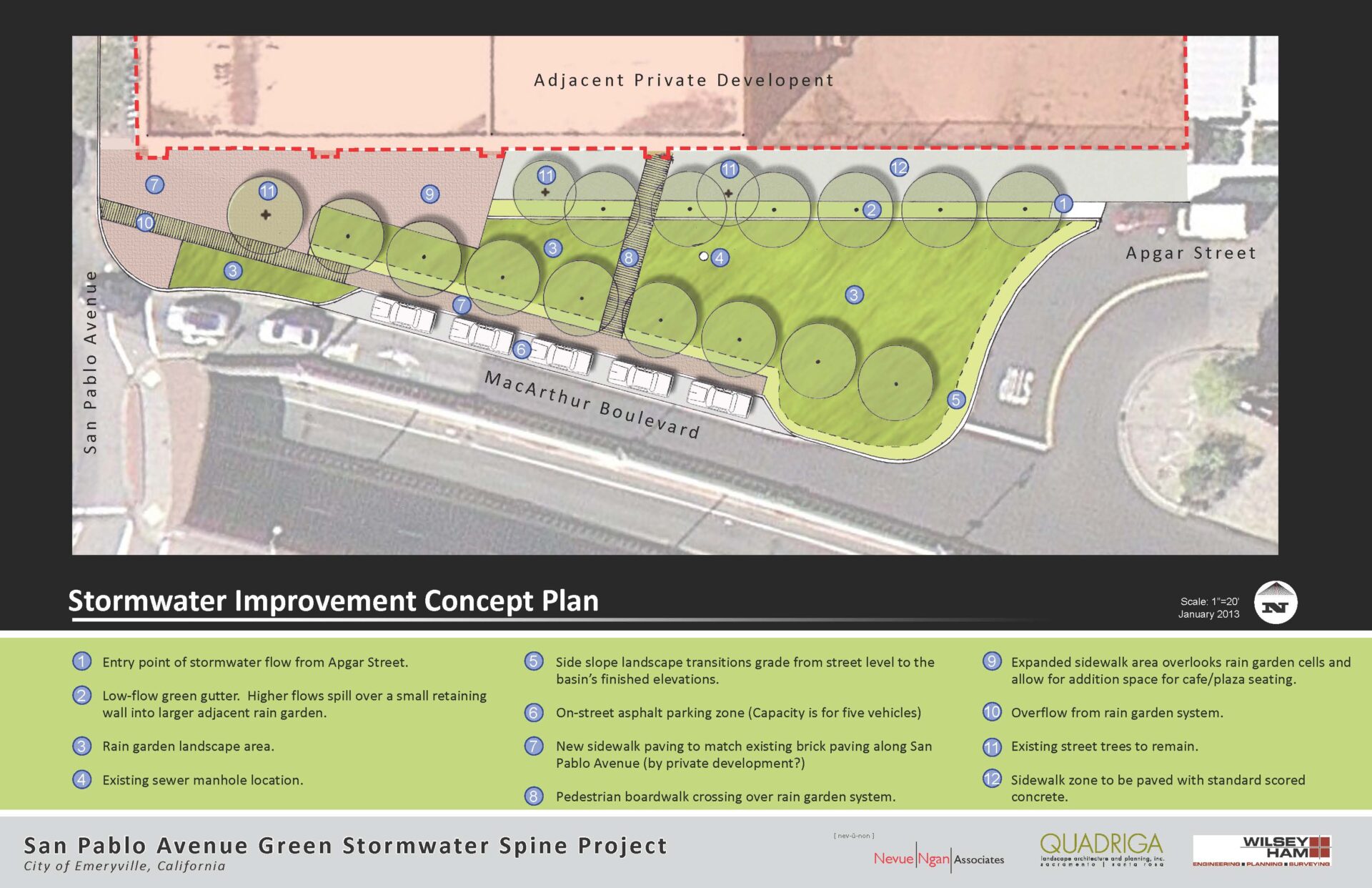

Scaling for Storms in Emeryville

Corner of West MacArthur and San Pablo

This is the largest and most involved garden of the SPINE project. Previously, the corner on West MacArthur and San Pablo was a giant paved triangle. But now, the site contains several species of sedges and hearty flowering plants like snowberry, punctuated here and there by empty plastic booze bottles.

“This was an opportunity for [us] to get funding to treat water in the public right of way,” says Michael Roberts, senior civil engineer with the City of Emeryville. “It is the most advanced publicly funded green-infrastructure project in Emeryville. Previous projects were pretty low-tech in comparison in that they dealt with water retention rather than water treatment.”

One of the most interesting things about the Emeryville SPINE site is that ongoing maintenance of the garden will become the responsibility of the private developer next door. Construction of the development was permitted while the rain garden was in its design phase, so as a condition of the building permit (which requires green-infrastructure improvements or changes to impervious surfaces for any new project larger than 5,000 square feet), the developer was tasked with future maintenance. This made its installation mutually beneficial.

Click to see enlarged slideshow.

Placemaking in Oakland

Corner of 16th and San Pablo

The Oakland SPINE site is right at the head of San Pablo Avenue; the street ends half a block later at Frank H. Ogawa Plaza. Of all the sites, the Oakland location feels the most folded into its surrounding environment — and the most successful at creating a sense of place. The garden is catty-corner to the Oakland Ice Center and shares the block with Hot Boys Chicken, which is a popular spot even mid-afternoon on a weekday.

The Oakland location captures the flow of a nearby triangular parking lot that is bordered by Jefferson and 16th. Cities, like private developers, are also required to abide by stormwater requirements issued by the SF Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board. “Our current permit requires us to make every effort to install as much green infrastructure as is feasible,” says Terri Fashing, Oakland’s acting watershed and stormwater manager. “We are required to reduce pollutants like mercury and PCBs, therefore all of the cities in the Bay Area are trying to find opportunities to incorporate green infrastructure into new capital improvement projects, which is very difficult to do in a developed area like the City of Oakland.”

Click to see enlarged slideshow.

Spinal Tap

In retrospect, a couple of larger lessons have been learned from the SPINE experience.

“It’s important to look at the costs and benefits of these projects and the likely future regime of drought and larger storms and ask what is cost-effective?” says Susan Schwartz, the president of Friends of Five Creeks, a citizen stewardship group. “Retrofitting might be a pipe dream and it might not be wise.”

SPINE project manager Josh Bradt agrees, suggesting that the best time to add green infrastructure is in parallel with other work to adjoining roads, sidewalks, drains, utilities, and redevelopment: “We learned that point-in-place projects solely for stormwater can be really complex, expensive, and have an intense permitting process. It’s probably better to do it in tandem with other infrastructure projects.”