Corps Experiments with Sediment Feed from Shallows

“Our project uses a light touch and lets water do the work.”

On a hazy winter day this past December two tugs pushed two scows back and forth across the glassy bay between the Redwood City shipping channel and the shallows off Eden Landing. What looked like your ordinary harbor dredging project, with an orange clamshell clawing up mud to make way for deep-drafting ships, was actually quite extraordinary. That’s because the destination of the mud-loaded scows was not a disposal site but a mile-long, 138-acre stretch of shallow water near Whale’s Tail marsh. This particular stretch of shallows has been carefully chosen by scientists and computer models because local conditions here — tides, winds, wave direction, depth, proximity to marshes — should all help deliver the sediment to the marsh and recharge mudflats. And goodness knows they need it. With sea levels rising, many San Francisco Bay marshes will eventually drown.

The Dillard, a U.S. Army Corps vessel that spends most of its time picking up wayward logs and other debris, chased the scows back and forth across the Bay while the planning team and a few reporters stood at the rails watching. In the period of an hour, we saw just one of the 100 trips the Corps estimates the scows would take to deliver 100,000 cubic yards of sediment. Watching it all, Corps scientist Julie Beagle couldn’t help exclaiming, “This is the best day of my entire life!”

Beagle has worked for over three years to shepherd the unusual project to fruition. She represents a newish Corps mindset that favors nature-based engineering over concrete flood protections. As the region scrambles to find more ways to deliver sediment to its drowning shores, Beagle has pursued the idea of strategic sediment placement in the water, a method that hadn’t been tried yet within San Francisco Bay.

It took a coalition of environmental groups led by the California Coastal Conservancy and the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC) to get amendments to the federal Water Resources Development Act in 2016, and again in 2020, that offered relief from the Corps’ long-standing least-cost disposal option policy, and local cost-share requirements. For decades, these policies had prevented more expensive experiments with the reuse of dredged material to build habitats, green levees, or pursue nature-based sea level rise adaptation projects.

At first, just the strategic placement pilot received funding in San Francisco Bay. More recently, the feds allocated $19 million for re-use around the Bay (both infusions come from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law). The proof is in the pudding: In 2022, the Corps reused 41% of the material dredged from the Bay, but for 2023 that amount is expected to climb to 80%. (Long-term funding covering the extra cost of reuse, however, is still in the wind.)

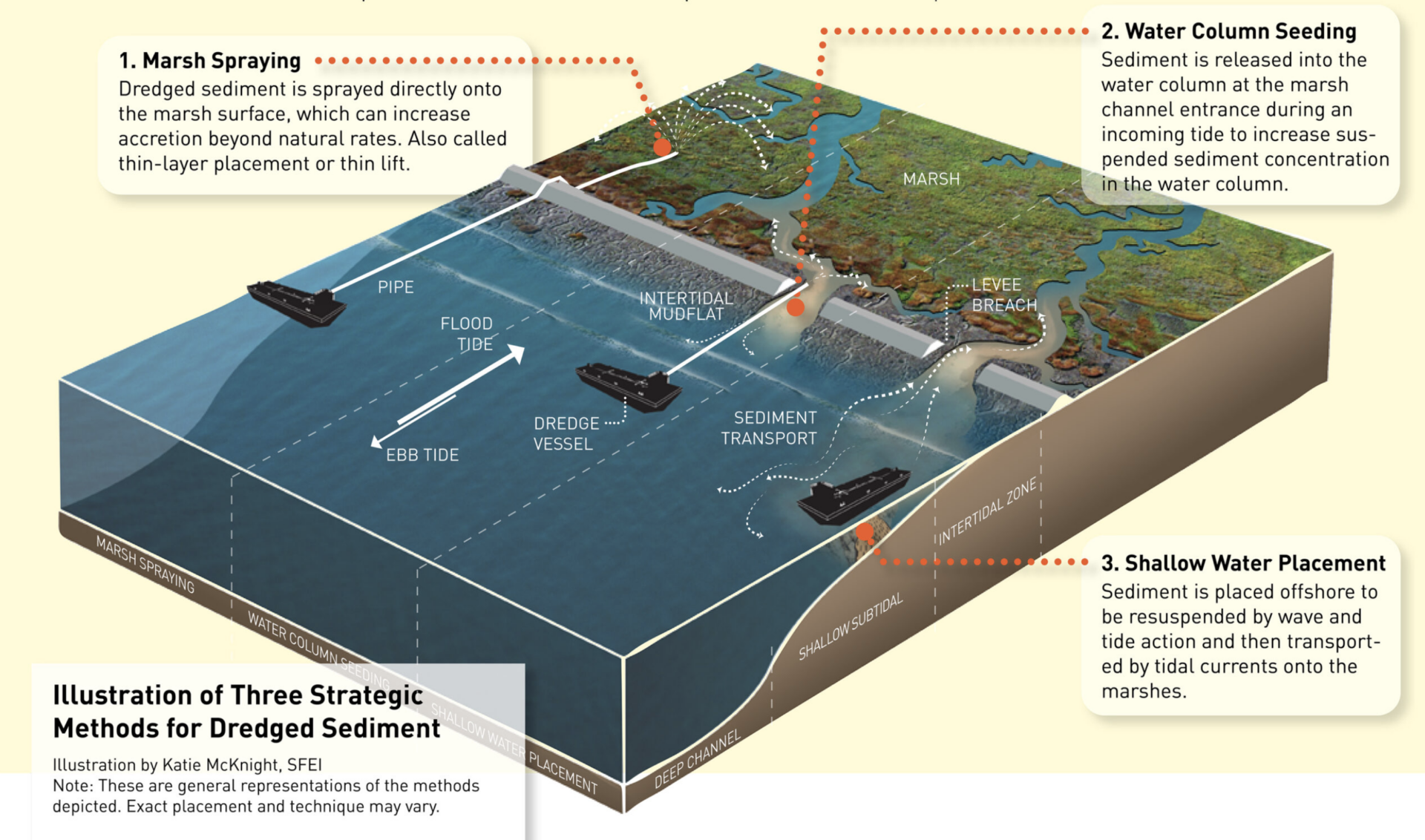

Options for sediment delivery to marshes. Art: Sediment for Survival, SFEI

For the pilot project, Beagle matched a dredging project with a nearby marsh site and applied for permits from regulators to undertake the experiment, which involves actually “filling” the Bay.

“This project pushes the edges of beneficial reuse techniques,” says Brenda Goeden, one of the regulators on deck to witness the event. Policies had to be changed at the local level too. “Without our 2019 Bay Plan amendment allowing fill for habitat benefits this pilot would not have been allowed,” explains Goeden, who manages BCDC’s sediment program.

“We know from testing which parts of the Redwood City harbor are clean enough to dredge for a re-use project, and there’s broad agency support for trying out this nearshore placement technique,” says Kevin Lunde, a senior environmental scientist with the SF Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board, and the other regulator on deck that day.

As the wind whipped around us and the horizon became an indistinct pearly gray mirror of air and water, members of the Corps planning team explained the modeling and analytic steps they used to get to this moment. The team examined 12 different possible sites for nearshore placement, comparing distribution at different depths, over narrower and wider footprints, and during summer and winter. “We were looking for a place where the wind-driven waves moved directly onto the shore,” says Beagle.

Modeling also suggested they needed the shallowest possible location negotiable by the tugs and scows at high tide. (Indeed, the project hired a contractor from Vancouver, Washington, HME Construction, which has smaller scows than the local options.)

After winnowing sites and techniques down to fewer alternatives, the chosen one, on view today, “uses a light touch and lets water do the work,” says Beagle.

As the clamshell scooped and dumped across the water, we joked that the crew appeared to be working faster now that they had an audience. Then project manager Peter Mull reminded us that Bay marshes need sediment to build up their habitats and remain healthy. “It’s like the blood in your veins,” he said.

Not all the sediment placed will end up on the plain of the target marsh, he said. Some will drift and settle elsewhere in the Bay; some may stay where the two scows are dropping it on this wintry day, producing the added benefit of slowing down waves that erode the marsh edge.

“This is a real-world science experiment and engineering-with-nature proving ground,” says Corps planner Arye Janoff.

Over the next year, scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey will monitor impacts on clams, worms, and other bottom dwellers, while others are checking on subtidal plants like eelgrass. Scientists will also track where the sediment moves via magnetic tracers attached to 1,000 particles tinted a bright green. In addition, the monitoring push is designed to dovetail with a major existing study of erosion and accretion at Whale’s Tail.

Clamshell at work. Photo: Brandon Beach

Corps’ Julie Beagle (left at back) explains project to reporters below deck. Photo: Brandon Beach

“We hope to get some really good science out of this project,” says Peter Mull.

“This was a sea change,” says Goeden, referring to the way the pilot project hasn’t been limited by the Corps’ least-cost and cost-share policies. “It’s a new golden era, with the Corps in the lead.”

“My dream is a marsh maintenance plan — a sediment sprinkler system for four to five needy sites,” says Beagle.

The Corps expects to spend about $3.6 million on the project. Local regulators and partners will be watching with bated breath as dozens of wetland restoration and flood protection projects around the Bayshore await sediment deliveries of one kind or another. Will it be a pipeline, an offloader, a truck or the Bay itself that drives deliveries going forward? All of the above will be needed, and as much — and as fast — as possible, the experts say.

Top Photo: Brandon Beach, USCOE.

More

- Crunching the Adaptation Numbers, (See Alameda County), June 2023

- Three Ways to Feed a Marsh, June 2021