Coho Salmon Remain Afloat Four Years After CZU Fire

Landslides. Falling trees. Scorched forests. These are just a few ways the 2020 CZU Lightning Complex Fire transformed habitats in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

But scientists are finding that the blaze’s effects on the region’s coho salmon have been small. “Fire is part of the natural landscape here,” says NOAA research ecologist Joe Kiernan. “And these fish have evolved with fire.” The blaze consumed nearly all of the Scott Creek watershed north of Santa Cruz, but surveyors in 2022 counted more baby coho in that creek than in any year since 2002.

Groups of coho salmon swim upstream from the ocean every winter to breed, a journey that has delivered fresh seafood to generations of Californians. But in recent decades their numbers have collapsed.

“I have been fishing the San Lorenzo [River] for 30-40 years,” says Curtis Smith of Felton. At first, the catch limit was ten, he says. Now scientists see less than ten spawning coho there in an entire year.

Highway 1 where it passes over the mouth of Scott Creek. Photo by Mark DeGraff

Other Recent Posts

Gleaning in the Giving Season

The practice of collecting food left behind in fields after the harvest is good for the environment and gives more people access to produce.

New Study Teases Out Seawall Impacts

New models suggest that sea walls and levees provide protection against flooding and rising seas with little effect on surrounding areas.

Oakland High Schoolers Sample Local Kayaking

The Oakland Goes Outdoors program gives low-income students a chance to kayak, hike, and camp.

Growing Better Tomatoes with Less Water

UC Santa Cruz researchers find the highly-desired ‘Early Girl’ variety yields more tomatoes under dry-farmed conditions.

Santa Clara Helps Homeless Out of Harm’s Way

A year after adopting a controversial camping ban, Valley Water is trying to move unsheltered people out of the cold and rain.

The Race Against Runoff

San Francisco redesigns drains, parks, permeable pavements and buildings to keep stormwater out of the Bay and build flood resilience.

Learning the Art of Burning to Prevent Wildfire

In Santa Rosa’s Pepperwood Preserve, volunteers are learning how controlled fires can clear out natural wildfire fuel before it can spark.

A 1994 report from the UC Davis Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Biology estimates that in the 1940s, 200,000–500,000 cohos trekked up the state’s rivers annually. But by the 1990s, less than 15,000 made the journey. The decrease was due to overfishing, climate change, and the destruction of the cold, clear streams where they lay eggs.

Coho salmon hatch on the gravelly bottoms of small creeks and pass their first year in pools of still water. Then they move to the ocean, where they spend another year or two gorging on sardines and other small fish. Upon reaching their adult size of 2-3 feet, cohos swim up rain-swelled coastal streams and spawn in the same place they hatched.

The salmon need healthy creeks to complete their life cycle, and they are weathering the changes the CZU Fire brought to Scott Creek.

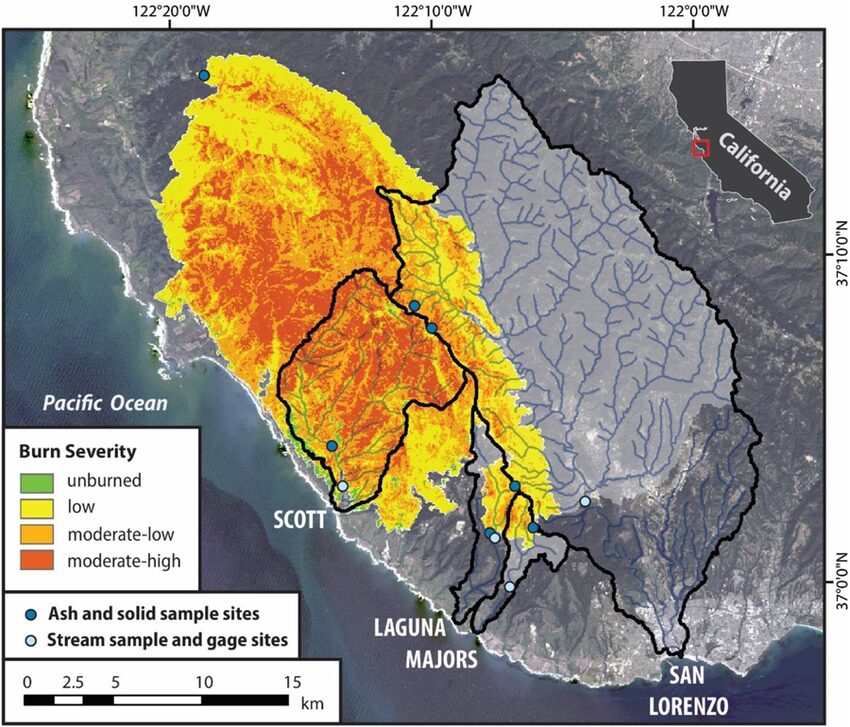

The 2020 CZU Lightning Complex Wildfire burn area. Map: Richardson et al. 2024

A 2023 NOAA report even noted a potential short-term benefit of fire. Some areas of Scott Creek had more water than expected during the 2020–2022 drought, likely because the blazes killed many thirsty plants that suck up stream water. “Increased flows in a creek are crucial, especially during the summer,” says Kiernan.

But fire is likely a net negative for the salmon, he adds. The wildfire incinerated the vegetation that held the soil in place, causing landslides that filled some of the pools of water where young salmon hang out. He attributes the bounty of juveniles in 2022 to a nearby hatchery and previous good ocean conditions that yielded a wave of egg-laying adults.

Damage from the CZU Fire in Big Basin State Park. Photo: California State Parks

In North America, coho salmon breed in coastal streams from Alaska to Santa Cruz. At the very southern end of their range, the Bay Area’s coho are on the frontlines of a warming world. Here, they are struggling to survive in drought-stricken streams and a heating ocean that contains less food.

Climate change might make these warmer, drier conditions common throughout northern California, said UC Santa Cruz coastal ecologist Eric Palkovacs in an interview with Salmon Nation. He said that Scott Creek, as the fish’s southernmost stronghold, might hold the key to surviving these conditions — its cohos are better adapted to heat and drought than their more northern cousins.

While the coho have proven resilient to the effects of fire, they are still swimming against the current. Their survival depends on the complex relationship between stream and sea conditions, which causes enormous annual fluctuations in their numbers.

“It’s boom and bust,” says Kiernan. “That’s the plight of these salmon and why they’re in jeopardy.”