Climate Zoning Defined for Burlingame Shore and Sonoma Hills

“Where and how you build can be among the most important decisions that are made in any community.”

Mention zoning to most people and they’ll likely think of height limits, density restrictions, or, if their memories are long enough, the notorious practice of racial redlining. But local zoning ordinances and other land-use regulations are taking on a new role in communities trying to mitigate or adapt to the impacts of climate change.

“One of the most effective forms of hazard mitigation is through tools that we already have in place: land use and building codes,” FEMA Region 9 Mitigation Division director Kathryn Lipiecki said at last year’s California Adaptation Forum. “Where and how you build can be among the most important decisions that are made in any community.” Zoning changes addressing sea-level rise are happening from Hawaii to Florida.

In the Bay Area, the city of Burlingame, with help from a new countywide agency in San Mateo County and a climate think tank in Washington, DC, just amended its zoning code to require higher ground-floor elevations and space for protective infrastructure in new development within an area vulnerable to sea-level rise. Other cities in the county and the region may follow Burlingame’s lead.

Elsewhere in the Bay Area, fire rivals flooding as a climate-related threat. In wildfire-prone Sonoma County, land management and permitting agencies are using other regulatory tools to buffer urban areas from wildland conflagrations. Both at the Bayshore and the forested edge of the metropolitan region, some jurisdictions are changing the rules for development and activities in flood and fire zones.

Zoning for Rising Tides: Burlingame

Like Sonoma and Marin Counties and San Francisco to its north, San Mateo County faces challenges from sea-level rise on two fronts. The Pacific Ocean gnaws at its western edge, and higher waters and tides threaten valuable real estate and vital businesses and infrastructure on its Bay side. Multiple studies show this county is uniquely vulnerable to sea-level rise, based on population and other metrics.

In some of its cities, notably East Palo Alto, housing is at risk. For Burlingame, flood-prone areas are a vital source of current revenue (according to city councilmember Donna Colson, 40% of the city’s revenue comes from hotels in the risk zone) and a site for future biotech development. The San Francisco Estuary Institute’s Shoreline Adaptation Atlas described Burlingame’s part of the Bayshore as the Bay Area’s most-developed landscape, with only 1% open space.

The process of updating Burlingame’s general plan started a conversation about sea-level rise in 2019. “It was an opportunity to develop standards we should be building into new development to better position ourselves for sea-level rise,” recalls community development director Kevin Gardiner. “We looked at elevations, what the science was telling us, vulnerabilities, options for protection.”

The city hired the consulting firm ESA and worked closely with OneShoreline, which had just subsumed the functions of the San Mateo County Flood Control District with an expanded mission and new governance. OneShoreline CEO Len Materman says the agency moved beyond traditional FEMA floodplain issues to “a more holistic look at climate change threats.”

For the Burlingame process, OneShoreline connected with the Georgetown Climate Center, a law and policy resource at Georgetown University Law School that maintains a clearinghouse for climate adaptation strategies; its staffers shared examples, best practices, and lessons learned from other areas in the US.

The amended zoning ordinance establishes a sea-level rise overlay district delineated by a map of future conditions based on FEMA flood maps. It’s currently zoned as commercial, with offices, hotels, restaurant, and some retail already in place. Within the district, new flood protection infrastructure along the Bay shoreline must be built six feet above the elevation a hundred-year flood would reach, with the first floor of new buildings at least three feet above that elevation.

The rising Bay surrounds San Francisco International Airport on three sides. Photo: Sierra Garcia.

City of Burlingame requirements for new construction within the sea-level-rise overlay district, and commercial and industrial zoning districts (C-1, BFC, I-I).

For now there’s no requirement to retrofit existing structures. The ordinance also requires developers to build and maintain protective infrastructure on the shoreline or leave room for its future construction. The nature of that infrastructure — gray or green — isn’t specified; the county is developing standards. “It’s likely that most people will do a levee and put the Bay Trail on top of that,” speculates Gardiner. Bioswales and other green-infrastructure features may also be in the mix. “We don’t really want a sea wall,’ he adds.

For Burlingame’s residents, the changes weren’t controversial. “We never had climate change deniers,” Gardiner recalls. “The public was saying ‘We need to be doing something,’ not, ‘Should we be doing something?’” He says most of the development community was on board from the start, and the rest came around after some initial pushback: “It’s in their interest to protect their investment. Some projects are already out the gate, ready to go. They’re saying, ‘You need to tell us what to do.’”

For the biotech companies with shoreline projects in the works, the expense isn’t a deal-breaker. “We don’t want developers and planners tripping over each other,” Materman comments. “So Burlingame is our first example of where we linked development projects to sea-level-rise zoning. It’s our way of underscoring how city land-use planning, new development, and the implementation of any shoreline-protection project should all be related.”

Gardiner says the ordinance is being revised to encompass groundwater inundation, a significant issue for the city and county where groundwater levels are already high. Groundwater will also be addressed in a regional project involving the Bayshore and the creeks that feed into the Bay, following the course of future high tides along the creeks and under Highway 101 to the Caltrain tracks. What to do to keep some San Mateo County stretches of 101 above water is uncertain.

Upgrades to San Mateo County’s Foster City seawall now under construction, and funded by a property-based assessment approved by voters. The improvements were inspired by FEMA flood map updates, resulting changes in flood insurance rates, and looming sea level rise.

Photo courtesy: Foster City Levee Improvement District.

One open question is how to fund protective infrastructure to fill gaps between privately-financed segments. “From an equity perspective, an assessment district would be the most straightforward and fair solution,” Gardiner says. “Inland areas would benefit from whatever resilience measures are put in. But a citywide parcel tax would be politically difficult.” Materman points out that any assessment district would be focused on areas affected by the city’s zoning ordinance and the larger county project, east of the Caltrain tracks.

Burlingame officials hope their initiative will inspire other communities in the county. Materman says there have already been conversations with other cities. “Our goal is for new development and infrastructure to function for decades as the impacts of climate change grow,” he reflects. “Many cities get this and want to plan ahead rather than do more difficult and costly retrofits later. Unfortunately, some don’t yet see the writing on the wall.”

As a next step, OneShoreline is working with East Palo Alto and South San Francisco on incorporating sea-level rise into their general plans, specific area plans, and zoning ordinances. With its relatively affluent population and strong tax base, Burlingame is better situated to take adaptive action than some other municipalities.

The View From Georgetown: National Perspectives

Katie Spidalieri, a senior associate at the Georgetown Climate Center, a nonprofit, nonpartisan entity founded in 2009, detailed some of the examples that Burlingame and San Mateo County officials evaluated in crafting their zoning changes. The Climate Center serves as a repository of federal, state, and local climate resources, including climate adaptation plans and laws, and maintains a State Adaptation Tracker. It appears that some local governments are taking advantage of existing regulatory tools even in states where climate change is, or was until recently, a political third rail.

Broward County, Florida, pioneered the concept of a zoning map of future conditions that Burlingame adopted in setting the boundaries for its new requirements. Norfolk, Virginia, is often described as having “the most resilience-oriented zoning ordinance in the country,” says Spidalieri. The Norfolk code incentivizes new development in less flood-prone areas and includes an innovative Resilience Quotient system, in which permits for certain types of development require proponents to earn points for risk reduction, green space preservation, and other categories.

The Hawaiian island of Kaua’i has what Spidalieri calls “the most progressive example of a setback ordinance,” based on measured coastal erosion rates. And after Hurricane Sandy, New York City amended its zoning code to make it easier for federal disaster funding to reach residents who wanted to elevate and floodproof their homes rather than building back to the pre-storm status quo.

The Hawaiian island of Kaua’i has what Spidalieri calls “the most progressive example of a setback ordinance,” based on measured coastal erosion rates. And after Hurricane Sandy, New York City amended its zoning code to make it easier for federal disaster funding to reach residents who wanted to elevate and floodproof their homes rather than building back to the pre-storm status quo.

“These jurisdictions are the exceptions rather than the norm,” Spidalieri notes. “The majority of cities and counties aren’t there yet. Leaders have to navigate issues of community support, equity, political support, and funding.”

Even in California and on the West Coast in general, examples are sparse (though the state has an adaptation clearinghouse and, in the Bay Area, Greenbelt Alliance recently released a Resilience Playbook of policies, planning guidance, sample ordinances and case studies).

Not every city enjoys Burlingame’s political climate. For many reasons, restricting or discouraging development in at-risk areas is politically fraught: “For example, if you restrict where people can live, you’re potentially pushing people out of the community and reducing the property tax base, especially if there are no higher-ground areas within the same cities to which people can relocate,” says Spildalieri.

And even if the Georgetown Center and the American Society of Adaptation Professionals are talking about managed-retreat scenarios, the concept tends to bring out the King Canute in local officeholders like Burlingame city councilmember Michael Brownrigg, as quoted in the San Mateo Daily Journal: “I don’t see retreat as an option.”

On Kaua’i, 72% of beaches are chronically eroding.

Photo: Ruby Pap.

The wind-whipped and drought-fueled 2020 Glass Fire spread from Napa County wildlands to Sonoma County suburbs.

Photo: John Burgess, Press Democrat.

Managing the Wildland-Urban Interface: Sonoma County

Sea-level rise is of course only one face of climate change challenges for the Bay region. Regulatory adaptation for the increasing risk of wildfire is more problematic. “While flooding isn’t a hundred percent predictable, there are models and tools available to help planners,” Spidalieri explains. “Generally, wildfire is more unpredictable, harder to think about on a data-driven basis.”

There are examples of local fire-protection buffer zones, notably in Boulder, Colorado, and in the plans for rebuilding California’s fire-ravaged town of Paradise, but fewer than for sea-level rise adaptation. And how would local regulations even begin to address tornadoes, or lethal heat domes?

Some attempts to reduce wildfire risks have encountered political obstacles. In 2020, California Governor Gavin Newsom vetoed SB 182, which was intended to limit how much housing local jurisdictions could allow in very high fire-hazard severity zones. His stated rationale was that the act “create[d] a loophole for regions not to comply with their housing requirements, fail[ed] to account for consequences that could increase sprawl, and place[d] significant cost burdens on the state.”

Meanwhile, local governments continue to make controversial land-use decisions: a Superior Court judge recently blocked a county-approved high-end residential development in Lake County, locale of recurrent major fires, because of inadequate planning for possible evacuation.

Rather than a 29-unit subdivision at the edge of fire-prone forest, this area of Sonoma County has become part of Saddle Mountain Open Space Preserve.

Photo courtesy: Sonoma Ag + Open Space.

After a four-year sequence of devastating fires, Sonoma County officials are vigilant. Tennis Wick heads the county’s Permit and Resource Management Department (Permit Sonoma), responsible for land-use planning and development in unincorporated areas and for fire prevention. He says most of the department’s applications involve wineries and cannabis growers.

Permit Sonoma discourages uses such as processing facilities with year-round employees and venues with events that would attract visitors. Most requests are site-appropriate: “These communities understand the constraints on human activity in high fire-severity areas.” He recalls one recent outlier: “The 2017 Sonoma Complex Fire burned along Los Alamos Road [near Santa Rosa]. The 2020 Glass Fire in the same general area took out most of the existing development along the road. Within a year we got an application to build a resort in exactly the same area. That’s not something we can permit. It’s astonishing that some folks just don’t get it.”

With the Biden administration’s first FEMA Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) grant — $37 million in federal funds, matched by $23 million from a PG&E settlement — Sonoma County is ramping up its fire-prevention efforts. “The culture of the community has embraced fire protection in a very significant way,” Wick notes. Permit Sonoma conducts annual property inspections and advises owners on defensive strategies, “working from the structure out and from the wildland in,” and partners with the Kashia Pomo and other indigenous communities on tribal lands.

There are limits to what the county can do, though. “People said we should be buying everyone out after the 2017 fires,” he recalls. “We estimated that would have cost $5 billion, not including environmental restoration.” The entire county budget at the time was only $1 billion. Recent studies by the Urban Land Institute and Next10, a green innovation initiative, have suggested transfers of development rights as a tool for shifting development away from fire-prone areas. Wick says that would be more feasible in an urban setting than in Sonoma County, with its myriad of small parcels, and would require complicated determinations of density and carrying capacity.

Buffering greenspace can help Sonoma’s homes, businesses and wildlife remain resilient to fire.

Map: Sonoma Ag & Open Space.

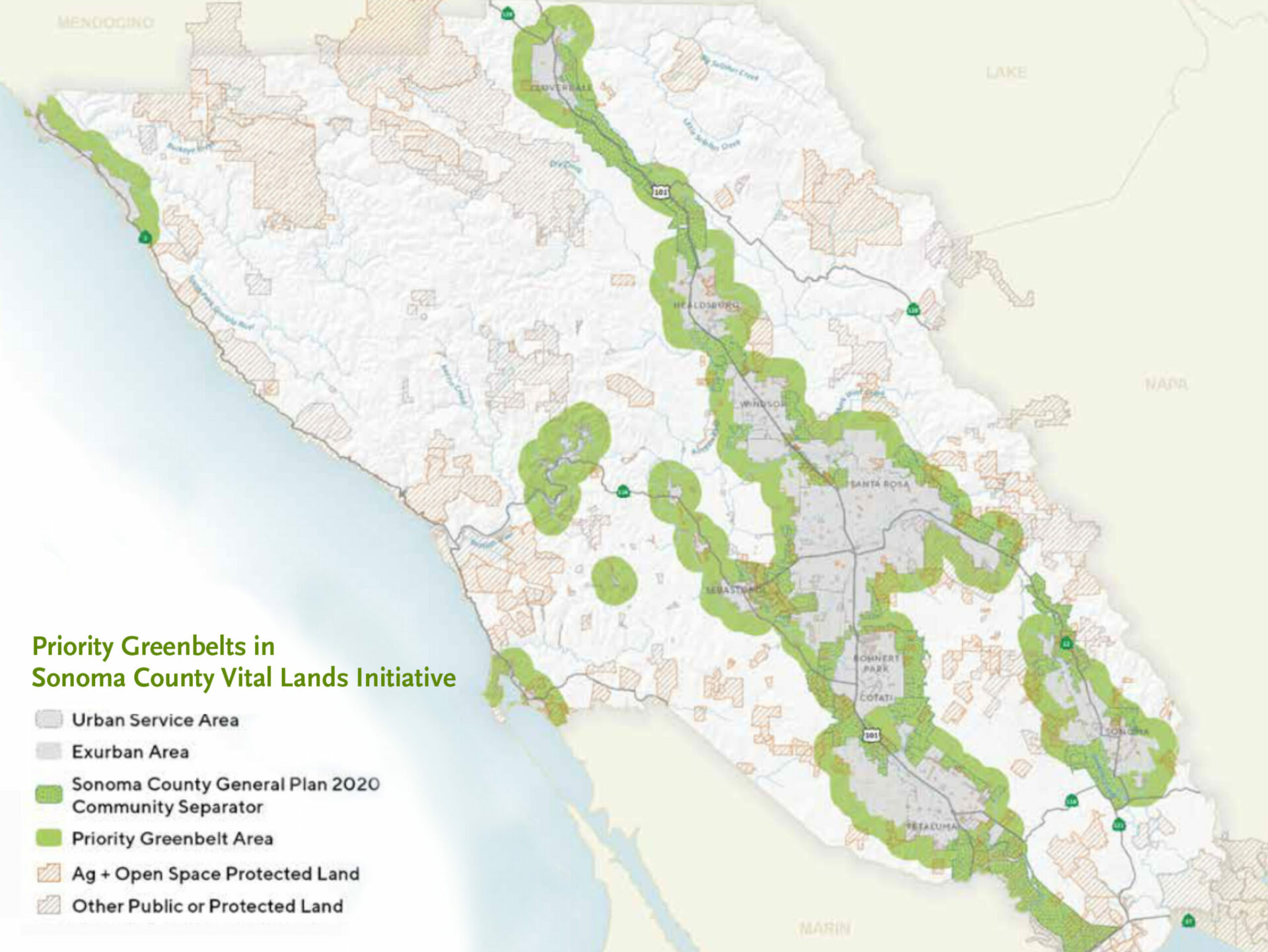

For its part, the Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District has been acquiring conservation easements in fire-prone areas and is working on creating priority greenbelt buffers around the county’s nine cities and several unincorporated communities. General manager Misti Arias says the district holds several easements in the Mark West Creek watershed, in the footprint of the 2017 Tubbs Fire, that restrict further subdivision and development.

The total price tag for the purchase of one group of properties that will become part of a new regional park was $23 million. These lands included up to 21 buildable lots. An earlier acquisition, a 960-acre property bordering the city of Santa Rosa, was slated for a 29-lot subdivision before it was purchased in 2006; it subsequently burned in the Glass Fire. It’s now the Saddle Mountain Open Space Preserve, protecting a mosaic of habitats and multiple special-status plant and animal species as well as serving as a wildfire buffer. “We have a fire ecologist on our staff working to implement land management practices to reduce the fire risk there and to the neighboring community,” says Arias.

The greenbelt buffers, part of the district’s Vital Lands Initiative, are a work in progress. “With the increase in fire risk, there’s renewed interest in undeveloped areas that are well managed,” Arias explained. The Ag and Open Space District is developing implementation plans and identifying the highest-priority areas for acquisition. Total costs haven’t been estimated, but acquisitions would be funded by a county sales tax that was approved in 2006 for a 20-year period; this year $26 million is available.

In addition to local initiatives like the ones in San Mateo and Sonoma counties, the Georgetown Climate Center tracks adaptation actions at the state level, including appropriations of adaptation funding for local governments. Spidalieri says 18 states now have comprehensive climate adaptation plans, and others have taken other types of actions. As she sees it, state-level action started in coastal states like Maryland and California, but has expanded from there: “Now there’s a wider geographic distribution, especially in the Midwest and Southwest.” Other states like Florida, Louisiana, and the Carolinas have been taking more significant steps.

But adaptation remains piecemeal. “There hasn’t been a lot of national guidance,” Burlingame’s Gardiner notes. He’s looking forward to a national climate adaptation conference this year: “It will be good to start developing a more national body of work.”

MORE

Greater San Francisco Bay Area

- Sustainable Burlingame

- OneShoreline, San Mateo County

- Burlingame preparing for sea level rise (San Mateo Daily Journal)

- Sonoma Ag & Open Space: Mark West

- Sonoma Ag & Open Space: Wildfire

- Sonoma Ag & Open Space: Saddle Mountain

- Resilience Playbook, Greenbelt Alliance, San Francisco Bay Area 2021

State and National

Wildflower bloom in Saddle Mountain Open Space Preserve. Photo courtesy: Sonoma Ag & Open Space.