Can Churches Lift Up Climate Resilience?

“Most poor folk think that this climate environment is for rich white people.”

“The earth is the Lord’s and the fullness thereof,” declares Reverend Frank Jackson, Jr. on Google Meet with a spark in his eye, quoting the Psalms. An ordained minister, he is president of the auxiliary council at his church in Inglewood and heads Village Solutions Foundation, a faith-based community development corporation that connects Black churches and communities with green energy programs. He begins his emails with “God morning” or “God afternoon” instead of “good morning” or “good afternoon,” and for him, there is no conflict between his Christian faith and climate action. On the contrary, God and climate (specifically clean energy) are wholly aligned.

Village Solutions partners with Southern California Edison to transform churches into energy ambassador sites, connecting church and community members with programs that save money and conserve energy, and hiring high school and college students to serve as energy ambassadors. This addresses the digital divide often seen in the Black community — leveraging the technical know-how of a younger generation to reach an older generation with information about energy conservation and preparing for wildfires and other extreme weather events.

Members of Jackson’s community engage in energy education. Photo: Village Solutions.

Jackson sees educating a younger generation as the key.

“Some of these [energy] mandates of 2035, 2040, 2045, 2050 and me being 69 — I said, well, it’s good information. But it’s really not going to do me a whole lot of good because by 2045, I don’t care what kind of energy I’m using, as long as I can stay warm.”

Village Solutions’ work in the energy sector shows that churches might be uniquely positioned — especially in the Black community — to build climate resilience for people who might otherwise not have access to government outreach or resources. Bridging this gap is crucial, because the same communities served by churches of color are often the communities most affected by poor air quality and extreme weather events, even if the media paints a different picture.

“Most Black folk, most Latino folk, most poor folk, really do think that this climate environment is for rich white people,” says Jackson. “That’s really because when they look at television and they see these big old mansions sliding down the hill — that ain’t them.”

Churches around California have the opportunity to help change this narrative — and to become hubs for climate action and resilience.

Energy saving outreach in church parking lot in Inglewood, California. Photo: Village Solutions.

Churches and climate messaging

There is less conflict between science and religion than we think, according to researchers who study the intersection of faith and skepticism about issues like the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change.

“What we found … is that there’s relatively few universal predictors of science skepticism,” says study co-author Chris Scheitle, professor of sociology at West Virginia University. “To the extent that there is one, it’s probably political conservatism.”

He cautions against using a simplistic “conflict-based narrative” that pits faith and science against each other. For example, although politically conservative Christians might be skeptical of climate change, many moderate or liberal Christians engage in climate organizing through their churches.

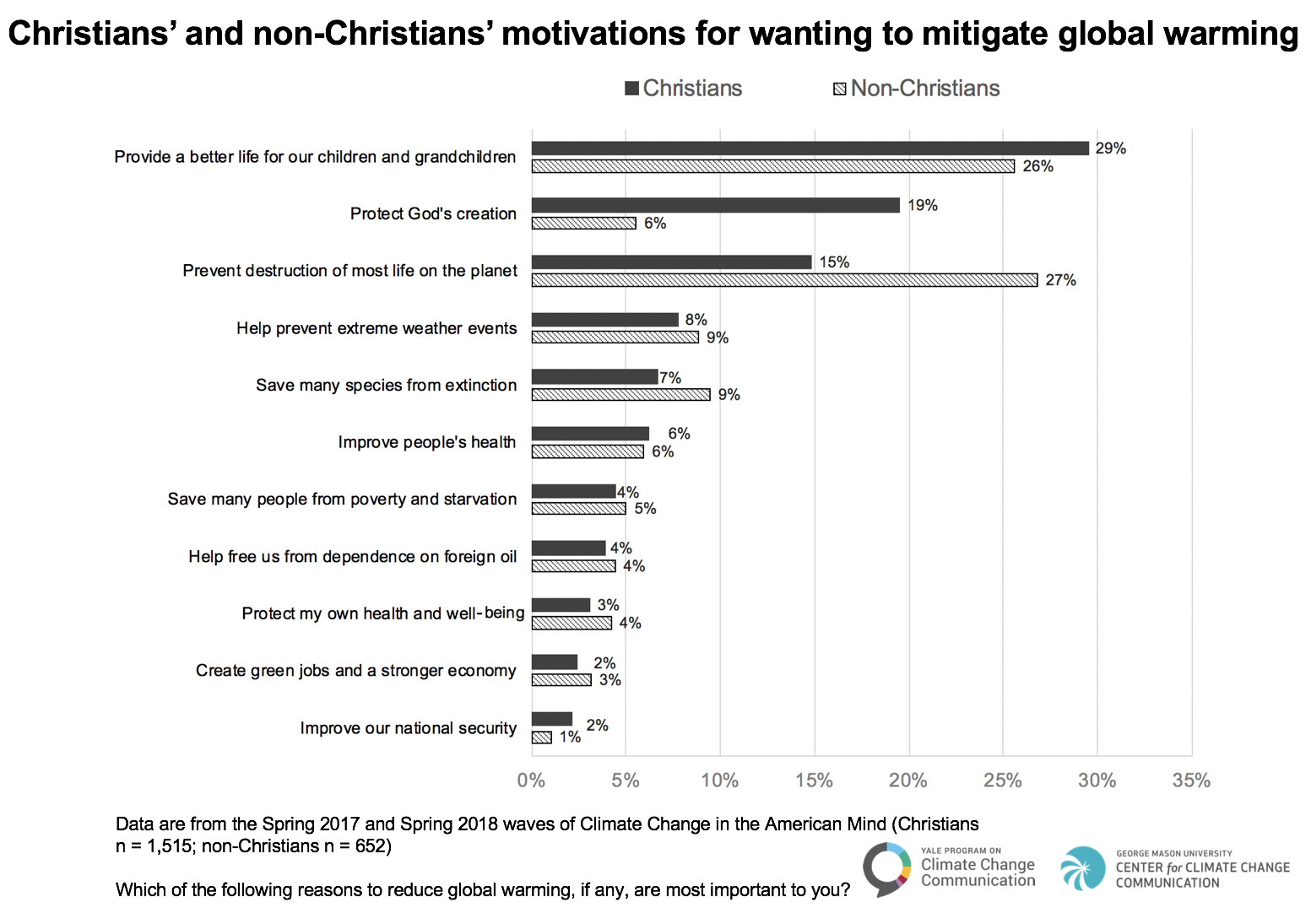

In fact, Christianity offers a ready-made framework for engaging with Christians and churches on environmental issues. The key is using a stewardship model, as explored in a 2019 Yale study: God created the Earth, the Earth is sacred, God has tasked human beings with caring for the Earth. In first-person language that might translate to: “I am a Christian, therefore I care for the Earth.”

“The problem here is that sometimes that political mindset gets activated,” says Matthew Ballew, one of the study’s co-authors and a research specialist at the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. “And there’s this concern that taking action on climate change is going to impact their individual freedom.”

Chart from Social Identity Approach to Engaging Christians in the Issue of Climate Change, Goldberg et al., SAGE Publications, 2019.

Instead of framing climate change as a political issue, organizations targeting faith-based communities should fit the message to meet the audience, experts say.

“The less you can focus on that narrative and more on the moral narrative — that this is the right thing to do, that this is something the Bible emphasizes, that we should be taking care of our land, we should be protecting people who are part of the land … the less you’re going to activate that political frame,” says Ballew.

Although Christians tend to have strong convictions about caring for the environment — many pray for the environment, according to Ballew — that doesn’t translate directly into belief about the urgency of climate change.

“They don’t really hear about it in church,” Ballew says. “And just in general, most Americans rarely hear about climate change from other people.

The power of community (and the pope)

Churches have something that is extremely valuable — the trust of the congregation in the church as a community and in the pastor as its lead figure, say experts.

Reverend Jackson at left with other faith leaders. Photo: Village Solutions.

There’s a cascading effect: If the pastor tries it, then people in the congregation will follow, whether it’s COVID-19 vaccination or replacing an air conditioner with an energy-saving heat pump. Jackson gives the example of new real estate agents, who are often encouraged to look to church communities for their first customers. At a Black church, he says, “If you can get that pastor to stand in that pulpit and endorse you, you’re gonna get some of those folk that’s gonna try you, just because.”

Village Solutions is currently working on a program for churches to replace their hot water tanks with heat pumps at little or no cost. This will then roll over into a residential program for households to get their water tanks replaced, starting at the top.

“If Pastor gets his water tank replaced, he’s gonna tell everybody at church … and now we can get the residential program put in because now we’ve got a sense of trust,” says Jackson.

Ballew points to a study from Yale and George Mason University on the “Pope Francis effect,” or how exposure to the pro-climate views of a religious leader can shift how Christians are thinking about global warming.

One center of Catholic community in San Francisco. Photo: Ariel Okamoto.

Churches as climate resilience hubs

As Ballew noted, Christian climate action is partly about caring for the environment, but it is also about protecting people. In California, churches in climate-impacted communities are exploring how to become climate resilience hubs, a safe space for the community to gather during extreme weather events. And energy companies like PG&E and state agencies like the California Strategic Growth Council are offering grant funding for communities, including faith-based communities, to create climate resilience centers.

While government agencies often try to connect underserved communities with the resources that they need, many communities are reluctant to trust the government due to systemic racism or neglect. If a church has invested time and resources into building a relationship with the surrounding community — listening to them, serving them, meeting their needs — it can serve as a trusted resource in a climate emergency.

Also, faith-based communities of color might be more receptive to taking action for climate resilience as extreme weather events become more common and harder to deny.

“There’s more acceptance of what’s right outside my front door,” says Nina Knierim, California area manager for the crisis-response group CORE, which does education and outreach with churches and other community-based organizations. “If I step outside my front door, I can feel the heat. If I step outside and try to get into my car and the street is flooding, I can see that water.”

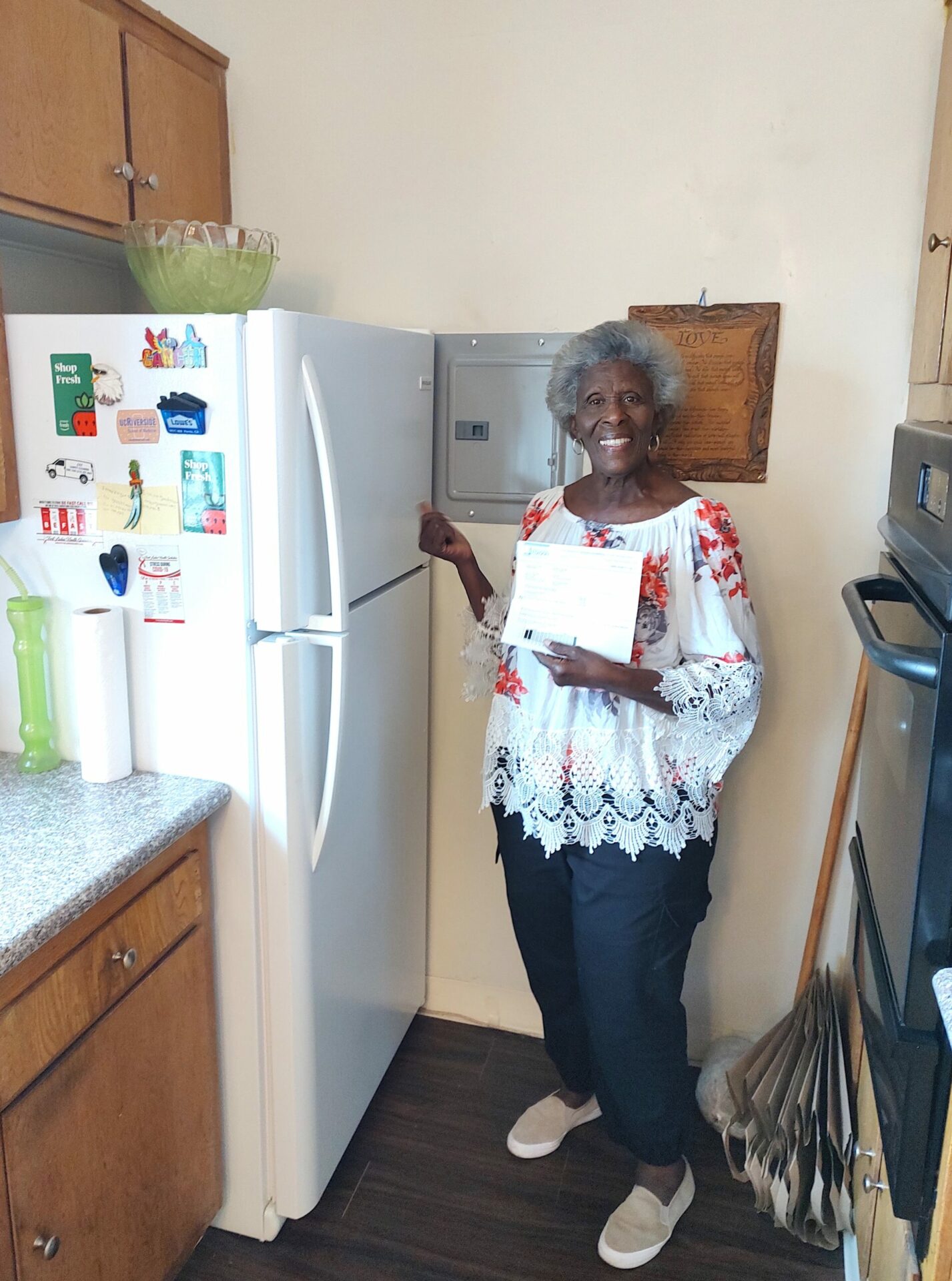

Village Solutions work with local utilities got Vilma Quinn a new fridge. Photo: Village Solutions.

Climate resilience workshop at Mudtown Farms in Watts, Southern California. Photo: CORE.

CORE’s team is currently working with Glad Tidings, a Black church in Hayward, to secure funding to create a climate resilience center. CORE first connected with the church during the COVID-19 pandemic, offering testing and vaccination to at-risk communities in the East Bay.

“On average, there’s this greater risk perception among communities of color compared to white communities, that climate change is going to harm them — harm their community, harm them personally,” says Ballew, noting that these studies did not specifically address religious status. “Communities of color tend to have stronger pro-climate views compared to white communities.”

The conversation becomes, “How do we live with this?” says Knierim. “How do we become more resilient to what’s going to be an everyday, every other day, every other week occurrence, so that we can continue to live, work, play, go to school, go to church, hang out with our friends, go to the movies — because life isn’t going to stop.”

Knierim notes that churches want to extend climate resilience beyond the boundaries of their church walls, and see it as another way to serve the broader community.

“[They’re] excited to have something else to offer,” she says. Churches have always served their communities with food, housing, and medical resources, “But here’s another way that even their facility or their grounds could be used in a way to benefit the community.”