Boxes of Mud Could Tell a Hopeful Sediment Story

Early results from 15 months of surveys in an experiment which placed sediment in the shallows to sustain nearby marshes in Eden Landing.

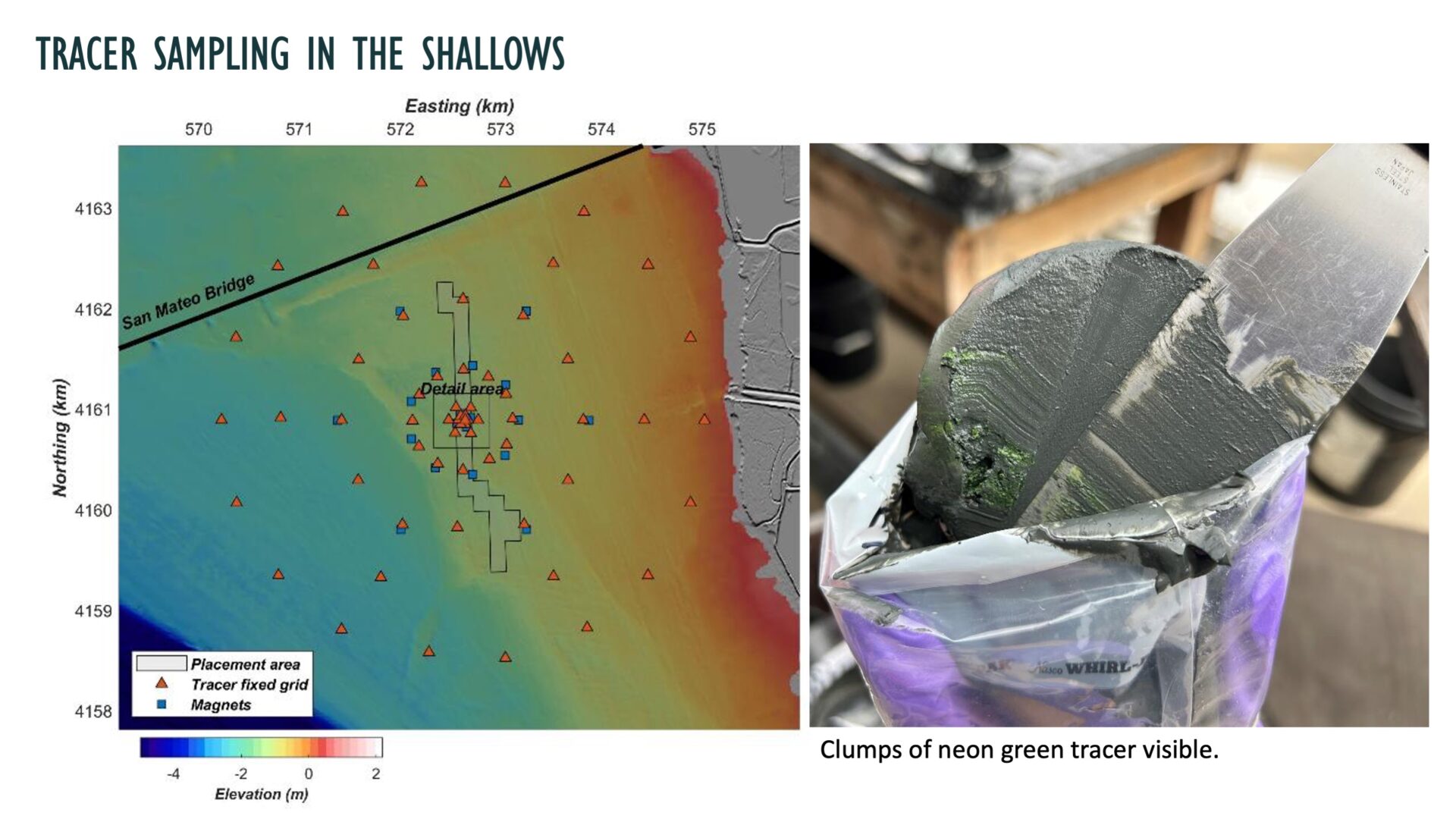

This March, six boxes of mud shipped to a company in England for analysis. Scraped off the marsh surface, stripped from field magnets, and scooped off silicon disks, science teams collected these 430 samples in recent months from the tidal channels and marsh flats around Eden Landing in South San Francisco Bay. The samples may contain tiny specks of neo-green, magnetized silt called “tracers.” While invisible to the naked eye in a lump of bay muck, these fluorescent tracers promise to reveal their travels under the microscope. It’s all part of an elaborate experiment in which scientists are feeding sediment to needy marshes threatened by sea level rise.

“I was really excited to see so many people invest so much time and energy in testing whether this new nature-based approach could work. It’s very forward-thinking,” says USGS research ecologist Karen Thorne.

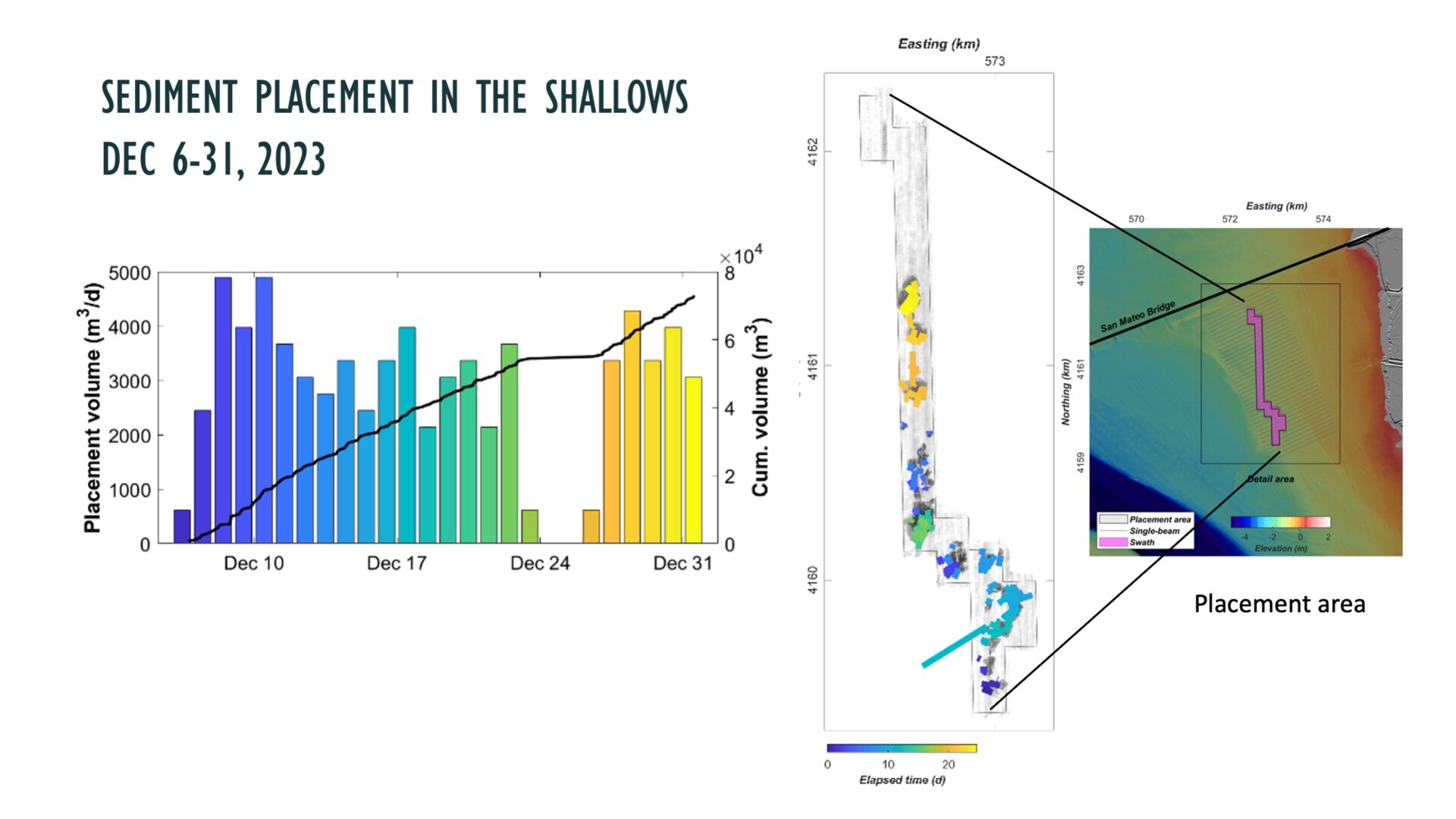

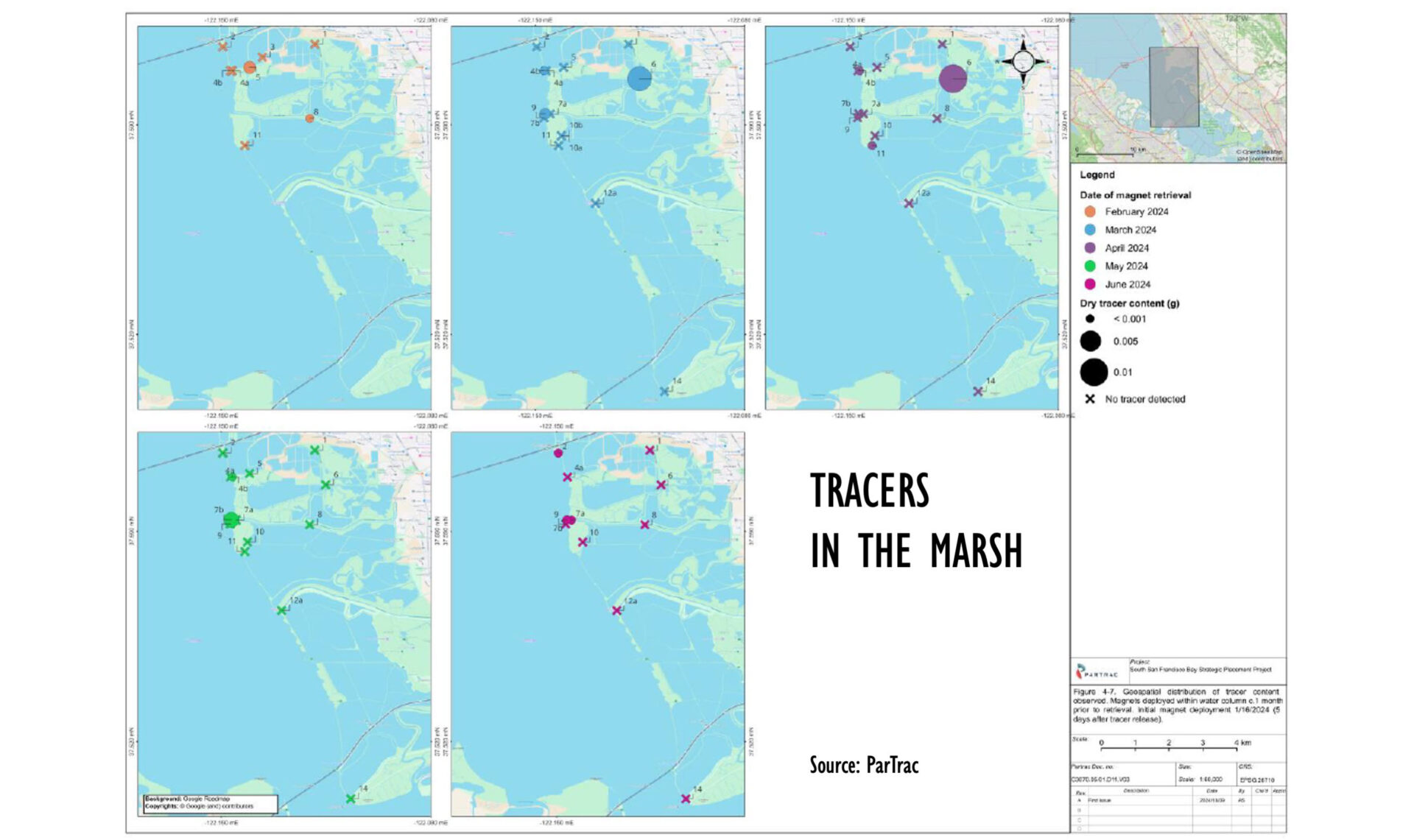

The experiment began in December 2023, when 90,000 cubic yards of sediment dredged from the Redwood City Harbor and 1,000 kilograms of magnetized tracer were placed in the shallows just offshore of East Bay marshes near the San Mateo Bridge touch down. What scientists want to know is: did the sediment migrate via wind, wave, and tidal action onto the nearby mudflats and marshes, or not? Fifteen months and numerous surveys later, they’re beginning to see the results.

“Bits from each monitoring group are filtering in, and we’re starting to tell the story, but it’s not the whole story yet,” says project lead Julie Beagle with the US Army Corps of Engineers.

Samples of life in the Bay-bottom oozes before and after placement. Photos: USGS

The science teams have been busy. First, they tracked plumes of sediment during the placement; then they began regular surveys of the elevation of the bay bottom throughout the placement site via side scan sonar. A biological team also began sampling how the clams, worms, and other critters in the oozes responded to being temporarily buried under new sediments, and whether the placement affected nearby eelgrass beds. All this time they’ve also been looking for those tell-tale neon green tracers.

“It’s a bit like looking for a needle in a haystack,” says Thorne. “But we’ve already found tracer all the way across the marsh and way back in the wetland restoration sites at Eden Landing.”

Thorne will have a deeper story to tell when those six boxes of mud have been unpacked and analyzed across the pond (aka Atlantic Ocean). But after collecting the samples out in the channels and marshes, largely via kayak, she can already attest to seeing some surprises. “Some of the gooey stuff stuck to those magnets, you had to wonder what was in it?” says Thorne.

Collecting sediment with magnets (center with bands of "gooey mystery guck") and silicon pads. Photos: USGS

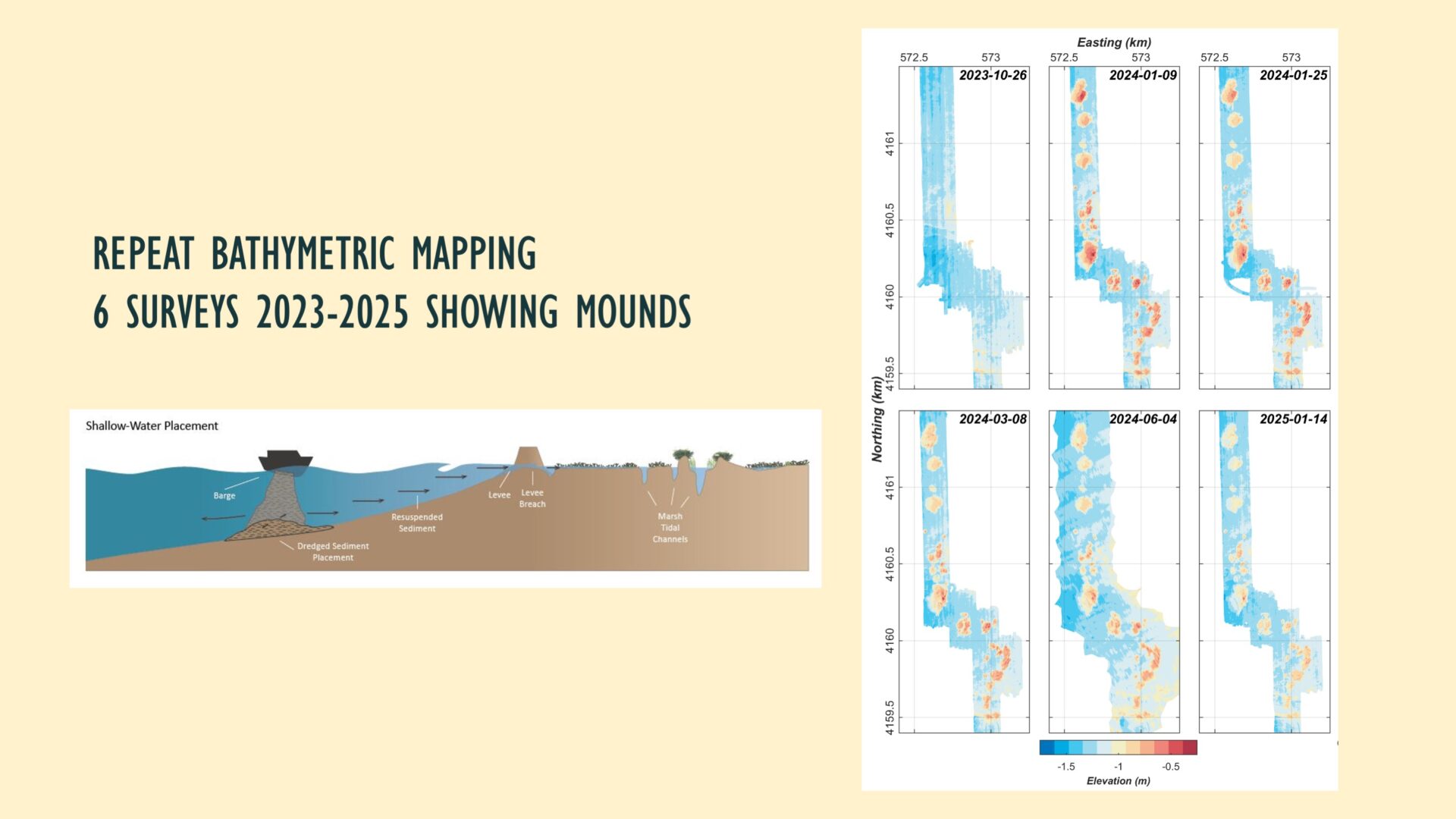

The results from the rest of the teams are also promising. And some of that has to do with the fact that dredgers dropped the sediment in mounds rather than spreading it out in a thin layer as originally planned.

Scientists seem to agree this was a “happy accident.” According to USGS Oceanographer Jessie Lacy, the bigger bulkier mounds were much easier to monitor than a smear of sediment almost indistinguishable, in terms of sonar, from the bayfloor.

During the placement, Lacy found that sediment plumes didn’t last long or reach far, and that the area returned to ambient conditions within a few hours. Surveys since suggest that the mounds have gradually been eroding, with the rate of erosion decreasing over time. More than a year later, one of the biggest mounds is down more than 50%, according to bathymetric scans.

“Given the big mounds, I expected the material to erode more quickly,” says Lacy. But based on the wave conditions and current speeds her team has since been recording, the results make sense to her. Such results will help scientists choose other sites for experiments. For example, if the mound erosion is going slowly in one of the Bay’s most energetic wave environments, then it’s probably not going to go more quickly in other areas, Lacy reasons. “If you wanted it to be faster, you’d need to put the mounds in shallower water where they would be impacted by waves more frequently. But given that this particular marsh is only eroding, but not drowning, having a reservoir of sediment in the shallows that is slowly being mobilized nearby is not necessarily a bad outcome.”

The RS Snavely conducts side scan sonar of the bay bottom and distributes the neon green tracers (see water) over the placement area. Photo: USGS

Project planners were also concerned about whether all the living things in the bottom oozes would get smothered by the mounds of sediment. A team led by USGS’s Susan De La Cruz, a wildlife biologist, looked at how long it took the bay bottom community to recover. They monitored pre- and post-project, and then again in June 2024, and looked especially at what was going on in the top five centimeters that provide food like invertebrates and crustaceans to hungry fish. While preliminary results found a big dip in community density and composition post-placement, they saw “community-level recovery” within six months.

“That’s a pretty fast recolonization,” says Beagle. “I would have expected more like three years. The smaller footprint of the mounds helped.”

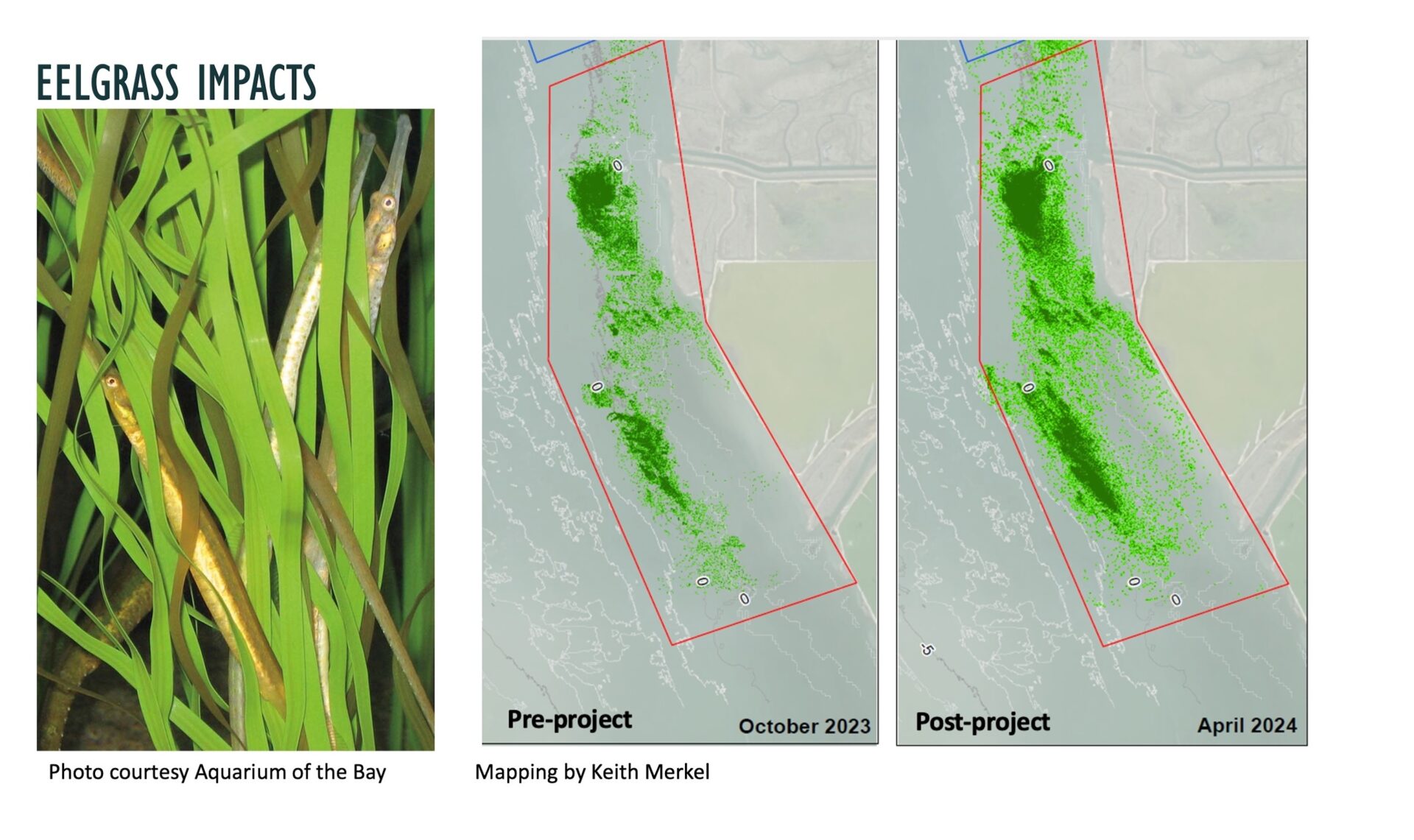

Under another monitoring initiative, scientist Keith Merkel mapped the eelgrass in the vicinity (but not within the project footprint) in October 2023 and then again in April 2024, bracketing the placement in December 2023. After a year, he found an 80% increase in the area of eelgrass and a 27% increase in eelgrass density.

“The bump in eelgrass is phenomenal but it likely has nothing to do with our project. It has everything to do with conditions, freshwater inputs, [and] estuary mixing. Eelgrass is going to come and go, but not because of a tiny amount of sediment placed a mile and a half away. That said, the good news is our project didn’t do anything bad to the eelgrass,” says Beagle.

Now the teams are crunching their numbers and finalizing their analyses, while waiting for the results on the travels of the neon-green tracer from the lab in England.

“To me, this is a massive win. It’s not the silver bullet. But as a tool being tested to help our shores keep pace with rising sea levels, these preliminary results suggest it’s effective, doable, and not harmful to the environment,” says Beagle.

Beagle is already looking around for the next project. The little marsh at the Bay Bridge toll plaza called the Emeryville Crescent is one potential candidate. Not only is it near critical infrastructure that could benefit from a buffering marsh, it has already been studied as part of the first pilot project. Another candidate is to put more sediment off Eden Landing in the rest of the pre-approved footprint (the mounds only cover 2/3 of the area). A third site in need of a sediment lift or feed could be Richardson Bay, where new mapping shows it is rapidly getting too deep for eelgrass.

“We can’t just sit back now — this is a pilot, and a pilot means you pilot it, you iterate, you do it again and learn more. The goal needs to be to get this approach, in whatever form it winds up taking, baked into the way we dredge and manage sediment, so that it’s like pulsing material to the marshes that need it at the time they need it,” says Beagle.

During Women’s History Month this article honors the contribution of women scientists in federal agencies sharing their science with the people who funded it, we taxpayers.