Bolinas Can’t Ignore Pacific Advance Much Longer

When the talk turns to planning for sea level rise, there’s a word less spoken: retreat. It’s sort of fun to pencil in marsh restorations, eelgrass beds, protective shell beaches, even seawalls. The thought that some inhabited areas may simply be indefensible in the long term is almost too grim to voice. But in one coastal Marin County village, an architect with nothing to lose has started a community conversation that may be the first of its kind on the California coast.

Steve Matson is a Bolinas elder. He moved to the village in 1970, just before a major oil spill fouled its beaches and galvanized local environmental action. As part of what was called the Future Studies Center, he helped scotch grandiose development plans around Bolinas Lagoon, and led in writing the locally generated Bolinas Community Plan. Half a century later, he is back with an idea to “save” downtown Bolinas in another way: by moving it.

Entering the town from the north on the Olema-Bolinas Road, you reach a Y of streets. Left is Wharf Road, leading down one little valley to the lagoon and a popular beach. Right is Brighton Avenue, following another trough to the sea. The community’s stores and services line these two axes. Straight ahead, in the cleft of the Y, is a residential hilltop called Little Mesa.

If you were at the end of Wharf Road about noon on March 22, you’d have seen a knot of people doing odd things with level, tape measure, and string. The man in the wheelchair was Matson. The man dangling tape over a railing to waterline was Will Bartlett, head of a local organization called the Bolinas Civic Group. Then a third fellow came along with his dog. “I’m a hydrologist and I’ve never seen it done this way before,” Rob Gailey recalls. Gailey was soon getting briefed on Matson’s brainchild, the Bolinas Sea Rise Initiative, supported by the Civic Group. He volunteered his expertise to help the work along.

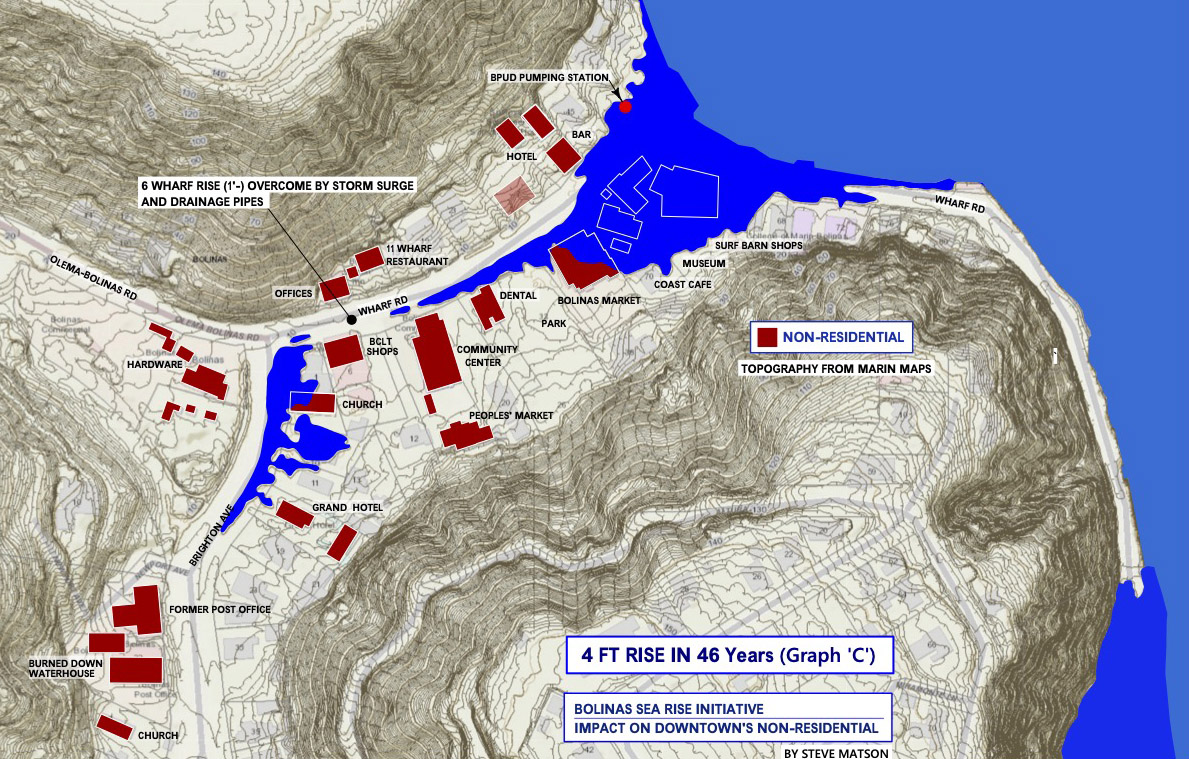

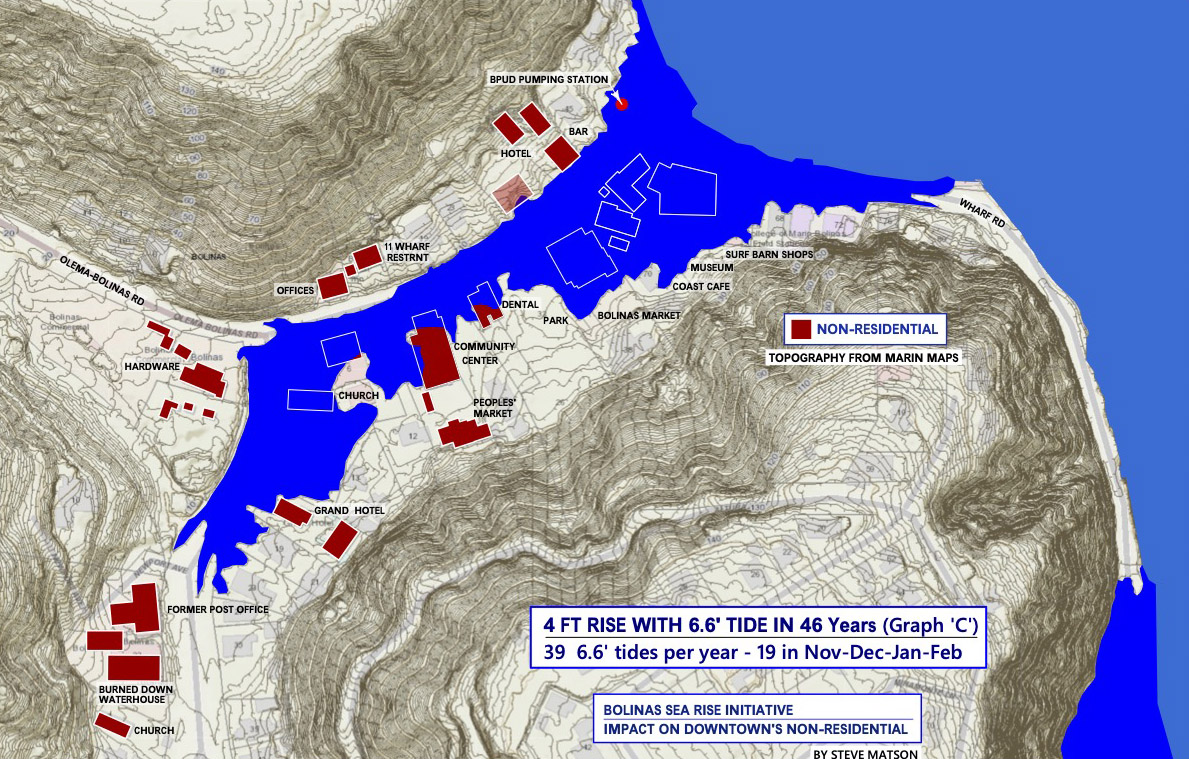

Official state guidance requires localities to plan for at least three feet of sea level rise by 2100. To be on the safe side, Matson had modeled about four feet. Adding the effect of spring tides and possible storm surge, he calculated that any building below nine feet above present sea level could face chronic flooding by the 2080s. That would threaten a dozen downtown businesses and organizations, including a church, a museum, a market, a café, a library, and the community center where the Civic Group meets.

Gailey’s research fine-tuned, but did not improve, the outlook. The timing of flooding is uncertain, but there is no doubt that it is on the way. A seawall, he estimated, might postpone the inundation till century’s end. Ultimately, he agrees with Matson: “Little Mesa will be an island.”

But Matson’s group has a solution in mind. One mile outside the current core, on the road leading toward the National Seashore, is a tract called Mesa Park. Run by its own tiny local agency, it now hosts a firehouse, a skateboard park, a health center, and playing fields. It lies about 180’ above the level of the sea. Matson has gamed out in detail how this spot could become the new heart of Bolinas.

The idea is not to transport existing structures. That’s just not on. Nor does Matson propose a sudden exodus. Rather, he envisions a slowly growing ring of modular structures surrounding a central plaza. The first occupants might be services that the little town lacks or has recently lost: a post office, an electric charging station, an industrial arts building. Then, as rising waters become a nuisance, one Wharf Road business after another could pack up and move. At a public meeting at Mesa Park on October 26, Matson deployed a pointer: “When the water gets to there, this activity can move up here.”

The obstacles to such a plan are enormous. Even to refine it, money will have to be found. Local and state plans will have to be profoundly amended. And a series of skeptical communities — beginning with Steve Matson’s neighbors and concluding with the Coastal Commission — will have to be brought around. At the October meeting, it was clear that the group still had far to go in publicizing the issue. “This is taking over the town,” one attendee complained.

Matson observes that there is still time to get accustomed to his idea (or to work up a better one). Just not too much time. “We could start a plan that would solve the worst problem confronting Bolinas in its history, so for God’s sake, let’s get serious about this,” he says.