Big Plans for Big Problems

“The big challenge in adaptation is do the solutions work for everybody? And is everybody bought into those solutions?”

October brought more than just a very welcome, albeit historic, rainstorm to parched and fire-scarred California—it also saw big advances for three major efforts to help the state and the Bay Area plan for a climate-altered future. Together, the plans both point the way toward a more resilient tomorrow, and expose some of the gargantuan challenges that could block the path.

Crafted over several years, with participation from dozens of local governments, agencies, community organizations, and others, these plans represent real progress in planning for a more resilient region in the decades ahead. But with weather, rising seas, and wildfire insistently demonstrating that the future is already here, the question is, when do we pivot from planning to action?

On the afternoon of October 21, the Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC) formally adopted the Bay Adapt Joint Platform, a strategy for protecting Bay Area people and places from rising seas. Later in the evening, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) and the Association of Bay Area Governments approved Plan Bay Area 2050, the region’s long-range plan for housing, transportation, economic development, and environmental protection that must be updated every four years per state law. In the meantime, the Newsom administration released a draft of the 2021 California Climate Adaptation Strategy, outlining the state’s key climate resilience priorities. The three plans overlap in many respects, and several of the same agencies and organizations are called on to realize them.

While the timing of having the regional plans adopted on the same day was coincidental, it is also a reflection of the ongoing coordination of the Bay Area’s regional agencies work to establish a foundation for managing the risks the region’s diverse communities face from climate impacts.

Zack Wasserman, the Chair of BCDC, which will act as a backbone agency and take the lead on several key actions, reflected on the “all hands on deck” approach BCDC and its many partners took to establish Bay Adapt. “We’ve got a very broad consensus agreeing, not simply to support this in print, but through their actions. A number of them have also agreed to take on leadership roles for specific elements of the platform.”

As a key staff lead in developing Plan Bay Area 2050, MTC’s Dave Vautin noted that “this was a major update to the regional vision that integrated adaptation in a really deep way for the first time. We incorporated strategies for things like sea-level rise, wildfire, and earthquakes into the overall planning process.” With its $1.4 trillion price tag, the plan lays out an ambitious vision of public policies and investments encompassing more than 80 actions. One theme in Plan Bay Area 2050 is “Reduce Risks from Hazards,” which outlines actions to protect shoreline communities affected by sea-level rise and retrofit buildings to make them more resilient to wildfire and earthquakes.

“Both plans are designed to establish guiding frameworks for how the range of projects needed to advance adaptation around the Bay area can be planned, funded and implemented, helping to prioritize those people, places, infrastructure and ecological assets that are at the greatest near-term risk,” says Allison Brooks, director of the seven-agency Bay Area Regional Collaborative. “The hope is this guidance will make arriving at a resilient region much more efficient.”

California sea lions are called the sentinels of the sea, for as they go, so goes the ocean. In a similar way, residents of the Bay struggling to adapt to rising tides will be human sentinels as climate impacts worsen. Bay waterfont exhibit of artist Ritodhee Chatterjee.

Also noteworthy is that all three efforts—Plan Bay Area 2050, Bay-Adapt and the State Adaptation Plan—center equity and include criteria requiring robust community engagement. “A lot of mistakes were made in the 20th century,” says Vautin, citing infrastructure projects that isolated minority communities and damaged them economically. “As we move forward with these 21st-century projects, we need to make sure that we’re advancing our environmental goals and tackling the climate crisis in an equitable manner.”

No doubt myriad local governments, agencies, nonprofits, and others will be critical to turning these plans into reality. Agencies like the State Coastal Conservancy, San Francisco Estuary Partnership, San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority, and others all have a role to play, says BCDC Planning Director Jessica Fain. “Each of them will be fulfilling a piece of what’s sketched out [in the Bay Adapt Joint Platform]. Plan Bay Area will do that through regional land-use policies, regional transportation policies, and investments. [The agencies] are really working together in a way that’s unprecedented.”

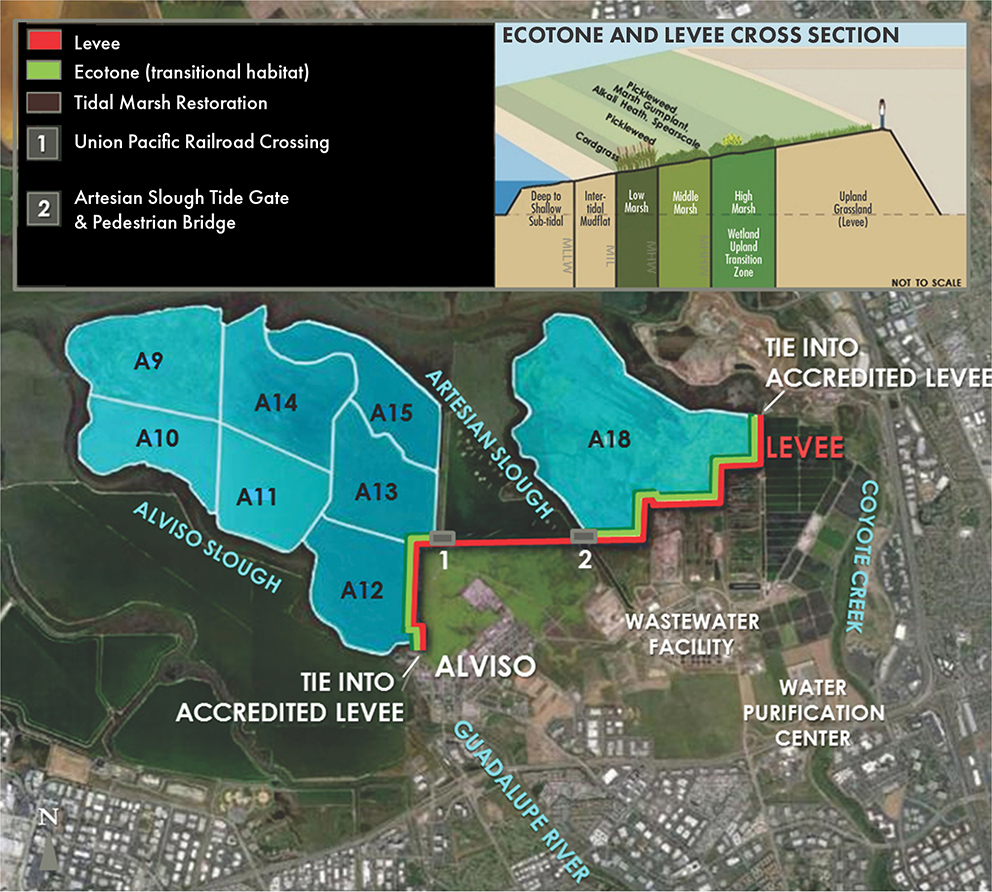

One of the region’s most ambitious levee projects, the South San Francisco Bay Shoreline Project, will protect low-lying Santa Clara County from sea-level rise and storm-related flooding. Construction, which will include a vegetated habitat levee around restored and former salt ponds (labeled A9-A18) is set to begin this November. Map courtesy Valley Water.

The state Climate Adaptation Strategy is another statutorily required update to an existing plan. The draft 2021 strategy is organized around five priorities, identifies specific actions, and incorporates other planning efforts—including Bay Adapt. “I don’t think it’s intended to be a final document,” says Ryan Ojakian of the Regional Water Authority in Sacramento. “It’s more about how we’re going to organize adaptation work moving forward.” He believes that partnership building, which the strategy identifies as a key priority, is critical. “The big challenge in adaptation is do the solutions work for everybody? And is everybody bought into those solutions? And that’s where I think partnership and collaboration unlock a lot.”

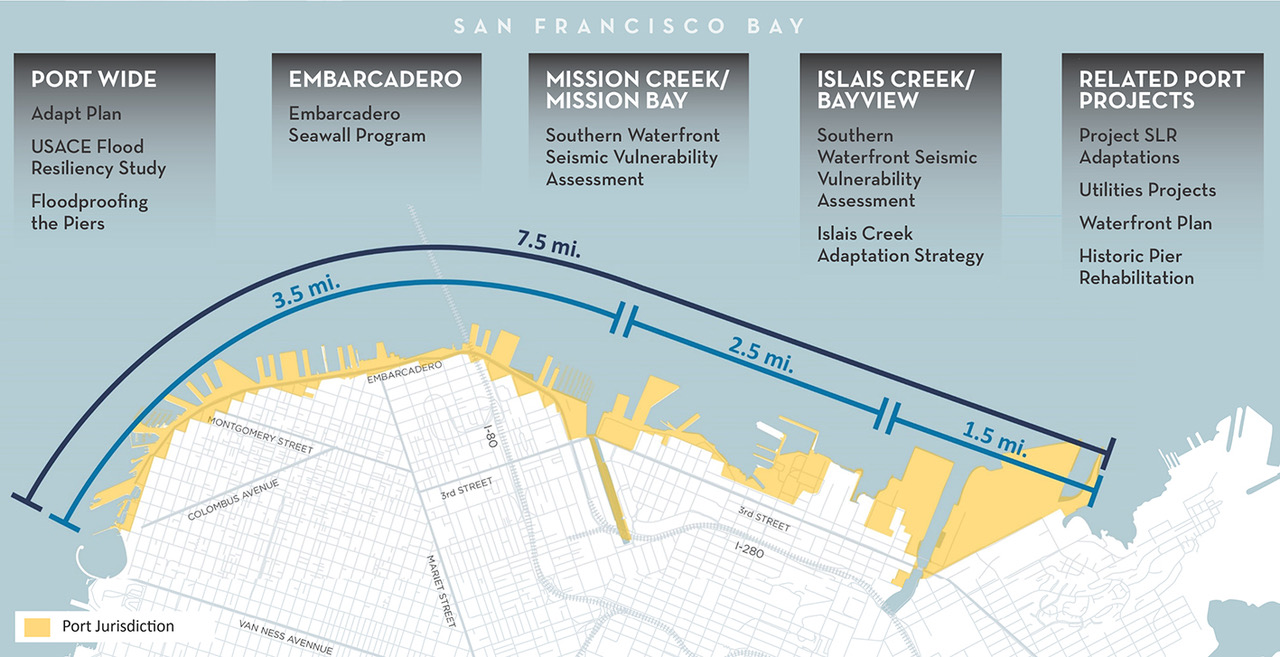

Planning to protect San Francisco’s overbuilt waterfront from rising seas has taken more than five years, hundreds of community meetings, and unprecedented inter-agency, inter-jurisdictional, public-private coordination. This November the Port presented several major projects in its waterfront resilience plan. The multi-billion-dollar price tag may be aided by the federal infrastructure bill.

Greenbelt Alliance’s Zoe Siegel, who participated in Plan Bay Area advisory board meetings, says resilience and equity are top priorities for her organization. “Overall, we were very impressed with the final outcome of Plan Bay Area. It’s extremely comprehensive, and really does create a vision for the region,” she says. “And Bay Adapt did a very good job of weaving in equity and environmental justice throughout the process in a way that I think really is transformative.”

“I think the big challenge with both Bay Adapt and Plan Bay Area is that there just isn’t the funding, or the capacity, or the governance structure to do most of these great things,” says Siegel.

Plan Bay Area projects that protecting the region’s shoreline from sea-level rise will cost $19 billion over the next 30 years. To put that in perspective, the state’s entire three-year resilience budget approved in September is only $3.7 billion, and much of that money is still to be appropriated.

Nevertheless, Vautin believes these new funding opportunities could allow the region to accelerate local planning work. “So, we can actually have a locally developed plan for every segment of shoreline that’s going to experience near-to-medium-term impacts,” he says.

Beyond the money and governance challenges, Wasserman and Fain see another problem: time.

Wasserman calls the gap between the pace of sea-level rise and the speed with which Bay Adapt is likely to be publicly accepted and implemented “a little scary.” But Fain notes that building the capacity of communities to lead won’t happen overnight.

“We don’t have unlimited time. We need to move as fast as possible without leaving communities behind,” says Fain. “It’s the next big thing we need to figure out.”

Disclaimer: Funding for this magazine is provided by the Bay Area Regional Collaborative.