Big Money but Short Deadlines for Regional GHG Reduction Projects

“We really needed to look for what shovel-ready projects we might have.”

Last September, the United States Environmental Protection Agency announced the availability of approximately $4.6 billion in funding to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The Climate Pollution Reduction Grant’s Implementation Grant invites state and local agencies across the country to apply with detailed plans on how they will measurably reduce harmful air pollutants, both in the short term (2025-2030) and long term (2030-2050). Awardees are expected to be announced in July.

In interviews with KneeDeep Times, several officials responsible for Bay Area CPRG applications, including representatives from the Association of Bay Area Governments, the Bay Area Air Quality Management District, and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, expressed gratitude for the federal government’s investment in climate resiliency through the Inflation Reduction Act, which funds the CPRG Implementation Grant. Winners of the highest-tier award can receive up to $500 million, and projects that lower emissions in low-income communities are more likely to receive funding.

However, the officials also shared their frustrations with the grant’s ambitious requirements. The workers had little time to complete the application and struggled to find projects that could significantly reduce emissions and be finished in five years.

Bay Area agencies began work on this project last summer when the EPA awarded the Air District $1 million through its Planning Grant. This funded the drafting of two documents: one detailing the Bay’s top greenhouse gas mitigation projects and another comprehensively documenting all of the region’s reduction efforts. The due date for the Priority Climate Action Plan was March 1, giving the Air District around five months to complete it. “That’s a very short timeline for a regional plan,” says Abby Young, a manager at the Air District who led the effort.

The plan itself acknowledges that the timeline “did not lend itself to the type of in-depth community partnering and engagement that has become best practice in the Bay Area.” To quickly gather ideas from the many ongoing initiatives in the Bay, Young says the Air District utilized artifacts from prior community engagement sessions, and synthesized the needs articulated in them to develop the main objectives for their Priority Climate Action Plan. Young says the Air District worked in a way that “complements and lifts up the local climate action and planning that have been going on for years in the Bay Area,” while also respecting the workers’ time.

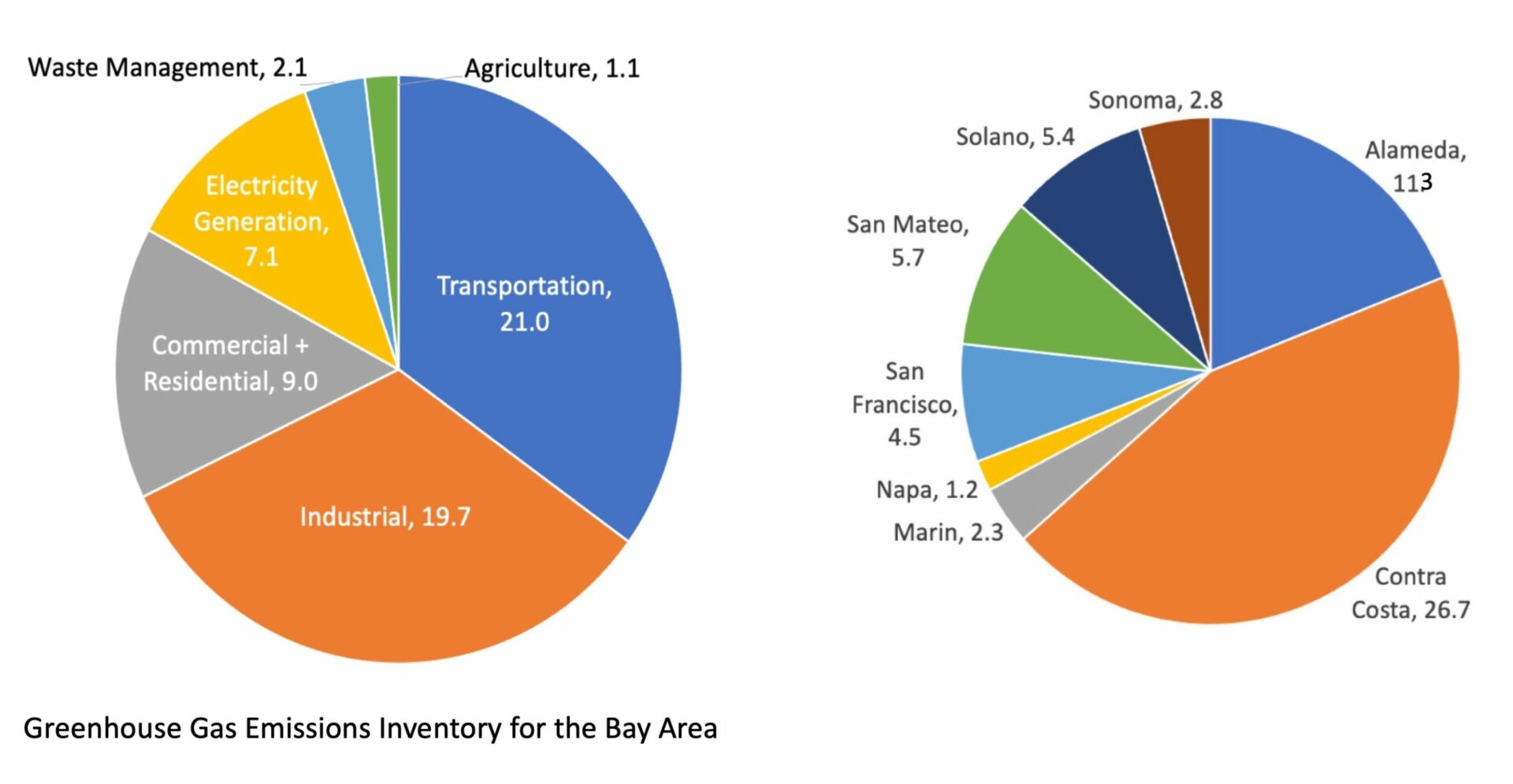

Greenhouse gas emissions inventory for the Bay Area region by sector and by county in 2022 (total of 59.9 MMTCO2 e). Source: Bay Area Climate Action Plan

The Air District’s plan prioritized greenhouse gas reduction projects in transportation and residential buildings, which together contributed 50% of the region’s emissions in 2022. The plan estimates that investments in transportation and electric vehicle stations could reduce C02 emissions by 172,000 metric tons, and that additional funding to decarbonize homes could reduce emissions by 363,000 metric tons.

The EPA invited local governments previously awarded priority plans to write implementation plans. In its September notice of funding for the implementation grant, the EPA stated that it will assess local governments on criteria such as the magnitude of greenhouse gas reductions, how much the proposal promotes the development of the transformative technologies, and how much disadvantaged communities will benefit from the project. The April 1 deadline required agencies to begin their implementation proposals as they finished up the priority plans.

Once the Air District identified transportation and residential buildings as the most promising areas, the MTC volunteered to draft the implementation proposal for mobility hubs, and ABAG wrote the plan for decarbonizing more housing. “They organically stepped up and said, we are going to lead these funding proposals,” Young says.

Resilience hubs and smoke-free cooling centers for the elderly or sensitive residents is another evolving priority in climate adaptation planning in the Bay Area. Art: Sophia Zaleski

Jane Elias, a director at BayREN (Bay Area Regional Energy Network), a branch of ABAG focused on energy efficiency, led its plan. BayREN applied to receive $98 million in funding for its Bay Area Clean Home Initiative, a project that electrifies and renovates homes in poorer communities overburdened by air pollution. From the initiative a single family-unit can receive $1,000 not only for energy retrofits, but also for house upgrades, such as infestation or asbestos removal services. BayREN plans to use funds from the implementation grant to make the Home Initiative project available for an additional 3,500 family units.

That BayREN’s project simply tacks-on to an existing project supports Young’s view that the short application cycle limited the Bay Area’s capacity to design more ambitious projects. “We really needed to look and see what shovel-ready projects we might have,” Elias says. Far from the 363,000 metric tons of CO2 projected in the planning application, Elias stated that their proposal to the EPA would lead to a reduction of 12,560 metric tons of C02 in the next five years.

Nonetheless, Elias remains enthusiastic about the grant, stating that receiving it aligns with BayREN’s top financial objectives. Both BayREN and the California Public Utilities Commission, the regulatory body that allocates a portion of ratepayers’ bills to fund BayREN, have expressed a desire to find additional income sources for BayREN.

Krute Singa, who led the development of the MTC’s implementation plan, had a more measured perspective on the grant. Fundamentally, Singa believes the five-year timeline stipulated for projects prevented the MTC from applying with a truly transformative project that would drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions – the types of project the EPA sought.

Bicycling remains a powerful way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and traffic. Photo: georgeclerk, I-Stock

Instead, the MTC proposed using EPA funds to improve ten BART stations. The improvements included additional Lyft bike stations and more lighting, ramps, and bike parking to enhance accessibility and safety. The MTC also plans to hire locals to promote a Clipper Card rebates program, offering discounts to low-income households for future BART rides.

However, Singa shared that even more modest projects like this one were difficult to fully implement given the constraints. She reached out to the Valley Transportation Authority in Santa Clara about teaming up, but the “five-year implementation timeline prevented them from joining our application.” She added that smaller transportation agencies were also too burdened to participate. “They’re all scrambling to keep service going, so they did not have the staff capacity to do something in five years,” she says.

The EPA stood by its timeline, saying in a written statement that “five-year grant performance periods are typical for federal grants” and that “this criterion speaks to the urgency of addressing climate change.”

Ultimately, the urgency of climate change, and the Bay Area’s eagerness to tackle it, forced the proposal writers to tolerate the EPA’s demands. They eventually came to appreciate how much camaraderie and alignment they developed through the process, Singa says, citing BART and Lyft in particular. “This was a great partnership … especially given the tight timelines, our partners really came together.”

Abby Young expressed joy that the $1 million planning award has incentivized the Bay to develop a holistic plan for greenhouse gas reduction. “This is the first time we will have a regional comprehensive climate action plan in the Bay Area,” she says.